INTRODUCTION

Non-traumatic severe tooth loss has been associated with an increased risk of stroke.(1)(2)(3)(4)(5) Enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines in response to chronic periodontal infection, endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis are the most likely pathogenic mechanisms underlying cerebrovascular consequences of severe tooth loss.(6)(7) The association between tooth loss and atherosclerosis is found not only in the intracranial vasculature but in the coronary and peripheral vascular beds as well.(8)(9)(10) Moreover, biomarkers of systemic atherosclerosis - such as arterial stiffness - have also been associated with tooth loss.(11) This is not surprising, since atherosclerosis has long been considered an inflammatory disease.(11)(13) Despite the above-mentioned evidence, information on the relationship between severe tooth loss and intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD) is limited. In the present study, we aimed to assess the association between severe tooth loss and ICAD in a well-established cohort of community-dwelling older adults of Amerindian ancestry living in rural Ecuador.

METHODS

Study population and design: The study was conducted in three neighboring rural villages of Coastal Ecuador (Atahualpa, El Tambo, and Prosperidad). Inhabitants of these villages share important demographic and epidemiological characteristics that include similar ethnicity (Amerindian ancestry), dietary habits, socio-economic status, lifestyles, and an overall comparable cardiovascular health status.(14) Using a population-based cross-sectional design, community-dwelling older adults (aged ≥60 years) residing in the above-mentioned villages were identified by means of door-to-door surveys, and then invited to undergo brain MRI, MRA of the intracranial vasculature, and a CT scan of the head. Those who signed a comprehensive informed consent form and had no contraindications for these exams were enrolled. Multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to assess the independent association between severe tooth loss and biomarkers of ICAD. The study followed the guidelines of the standards for reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE),(15) and was approved by the I.R.B. of Hospital-Clínica Kennedy, Guayaquil (FWA 00006867).

Tooth loss assessment: A rural dentist performed an oral exam in order to ascertain the number of remaining teeth. Individuals were asked if they had lost teeth as the result of trauma or extraction by means of a professional. Traumatic tooth loss was not counted for purposes of this study. Having <10 remaining teeth was used as the cutoff for defining severe tooth loss and to assess its association with cardiovascular risk factors and diseases, as detailed elsewhere (Figure 1).(3)(16)

Clinical covariates: Demographics and cardiovascular risk factors were ascertained using previously described interviews and procedures.(14) The American Heart Association (AHA) criteria were used to assess cardiovascular health metrics.(17) A poor smoking status was designated if the subject was a current smoker, a poor body mass index if ≥30 kg/m2, a poor physical activity if the subject engaged in no moderate or vigorous physical activity, a poor diet if the individual had none or only one component of the AHA healthy diet, a high blood pressure if ≥140/90 mmHg, a poor fasting glucose if ≥126 mg/dL, and a poor total cholesterol levels if ≥240mg/dL. The brachial pulse pressure was considered increased if >65 mmHg.(18) A total of 101 individuals were receiving antihypertensive medication, 55 were on hypoglycemic drugs, and 13 were on statins with 19% taking drug combinations. Interviews revealed that these drugs were often taken at suboptimal doses, precluding their use as a reliable covariate.

Neuroimaging studies: High resolution CT was used to assess calcium content in the carotid siphons, MRA for assessment of significant segmental stenosis of major intracranial arteries, and MRI focused on the presence of neuroimaging signatures of cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD) and other (non-lacunar) stroke subtypes. Neuroimaging studies were performed at the Hospital-Clínica Kennedy (Guayaquil), with a Philips Brilliance 64 CT scanner and a Philips Intera 1.5T MR scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, the Netherlands).

For CT, slice thickness was 3mm with no gap between slices. Digital images were viewed on the Osirix Medical Imaging software (Pixmeo, Geneva, Switzerland) using the bone window setting to identify and grade carotid siphon calcifications (CSC). Individuals were stratified into those with low and high arterial calcium content; the latter was defined as the presence of uni- or bilateral thin confluent or thick interrupted or continuous calcifications (Figure 2).(19)

Figure 2 High resolution CT with bone settings showing high calcium content in the right carotid siphon (arrow).

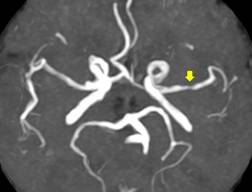

MRAs were performed using a three-dimensional time-of-flight sequence; slice thickness was interpolated at 1mm. Significant stenosis of major intracranial arteries (≥50%) were assessed by the WASID method,(20) which was subsequently validated for MRA (Figure 3).(21)

The MRI protocol included two-dimensional multi-slice turbo spin echo T1-weighted, fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), T2-weighted, and gradient-echo sequences in the axial plane, as well as a FLAIR sequence oriented in the sagittal plane. MRI readings focused on the assessment of neuroimaging signatures of cSVD and other (non-lacunar) stroke subtypes. White matter hyperintensities (WMH) of presumed vascular origin were defined as lesions appearing hyperintense on T2-weighted images that remained bright on FLAIR (without cavitation) and graded according to the modified Fazekas scale into none-to-mild and moderate-to-severe.(22) Cerebral microbleeds (CMB) were rated according to the microbleed anatomical rating scale; only definitive CMBs, as seen on the gradient-echo sequence were included.(23) Lacunes of presumed vascular origin were identified on the T1-weighted sequence and defined as fluid-filled cavities measuring 3-15mm located in the territory of a perforating arteriole.(24) Enlarged basal ganglia perivascular spaces (BG-PVS) were defined as abnormal if >10 of these lesions were present on the T2-weighted sequence in a single slice in one side of the brain.(25)

All neuroimaging exams were read by one neurologist and one neuroradiologist blinded to clinical data. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the aid of a vascular neurologist. Kappa coefficients for interrater agreement were 0.81 for the presence of high calcium content in the carotid siphons, 0.73 for significant stenosis of intracranial arteries, 0.93 for WMH, 0.82 for CMB, 0.88 for lacunes, 0.84 for the presence of >10 enlarged BG-PVS, and 0.90 for the presence of other stroke subtypes.

Statistical analysis: Data analyses were carried out by using STATA version 16 (College Station, TX, USA). In univariate analyses, continuous variables were compared by linear models and categorical variables by the x 2 or Fisher exact test as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to assess the independent association between severe tooth loss and ICAD, after adjusting for relevant confounders.

RESULTS

From a total of 712 community-dwelling individuals aged ≥60 years identified during door-to-door surveys, 590 (83%) underwent all prescribed exams. Of the remaining 122 individuals, 53 refused to participate, 42 died or migrated between enrollment and the invitation, 14 had severe disability and could not be transported to Guayaquil, 12 had claustrophobia during MRI, and one had an implanted pacemaker. Nine additional individuals were excluded from analysis because motion/metal artifacts precluded proper interpretation of CSC on CT. With the exception of individuals reporting poor physical activity, there were no significant demographic differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors across the 581 participants and the 131 subjects with incomplete exams (Table 1).

Table 1 Differences in demographics and cardiovascular risk factors across Atahualpa, El Tambo and Prosperidad residents aged ≥60 years included and non-included in this study (univariate analyses).

| Included individuals (n=581) | Excluded individuals (n=131) | p value | |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 71 ± 8.4 | 71.8 ± 9.7 | 0.339 |

| Women, n (%) | 332 (57) | 65 (50) | 0.117 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 21 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.099 |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m 2 , n (%) | 147 (25) | 24 (18) | 0.091 |

| Poor physical activity, n (%) | 66 (11) | 33 (25) | <0.001* |

| Poor diet, n (%) | 55 (9) | 14 (11) | 0.669 |

| Blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, n (%) | 250 (43) | 67 (51) | 0.091 |

| Fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, n (%) | 176 (30) | 41 (31) | 0.821 |

| Total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, n (%) | 69 (12) | 11 (8) | 0.255 |

| Brachial pulse pressure >65 mmHg, n (%) | 222 (38) | 59 (45) | 0.148 |

*Statistically significant result

The mean age of the 581 participants was 71±8.4 years (median age: 69 years) and 332 (57%) were women. Severe tooth loss was present in 269 (46%) individuals. Twenty-one (4%) were current smokers, 147 (25%) had a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, 66 (11%) had poor physical activity, 55 (9%) had a poor diet, 250 (43%) had blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, 176 (30%) had fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, 69 (12%) had total cholesterol levels ≥240 mg/dL, and 222 (28%) had a brachial PP was >65 mmHg. Moderate-to-severe WMH were identified in 165 individuals (28%), CMB in 62 (11%), lacunes - silent or overt - in 62 (11%), >10 enlarged BG-PVS in 177 (30%), and other (non-lacunar) stroke subtypes in 33 (6%).

ICAD was diagnosed in 205 (35.3%) individuals. Of these, 165 only had high calcium content in the carotid siphons, 20 only had significant stenosis of at least one major intracranial artery, and 20 had both biomarkers. The remaining 376 individuals had no evidence of ICAD on CT or MRA.

In univariate analyses (Table 2), covariates associated with ICAD included increasing age, poor physical activity, high blood pressure, high fasting glucose, high brachial pulse pressure, presence of moderate-to-severe WMH, CMB, lacunes, >10 enlarged BG-PVS, and other stroke subtypes. Interestingly, a poor body mass index showed an inverse significant association with ICAD (obesity paradox), as previously reported by our group.(26)

Table 2 Univariate analyses showing differences in characteristics of Atahualpa, El Tambo and Prosperidad residents aged ≥60 years across categories of intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD).

| Variable | Total series (n=581) | No ICAD (n=376) | ICAD (n=205) | p value |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 71 ± 8.4 | 69.5 ± 7.6 | 73.8 ± 9 | <0.001* |

| Women, n (%) | 332 (57) | 220 (59) | 112 (55) | 0.367 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 21 (4) | 13 (3) | 8 (4) | 0.784 |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m 2 , n (%) | 147 (25) | 106 (28) | 41 (20) | 0.029*‡ |

| Poor physical activity, n (%) | 66 (11) | 32 (9) | 34 (17) | 0.003* |

| Poor diet, n (%) | 55 (9) | 34 (9) | 21 (10) | 0.636 |

| Blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, n (%) | 250 (43) | 139 (37) | 111 (54) | <0.001* |

| Fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, n (%) | 176 (30) | 90 (24) | 86 (42) | <0.001* |

| Total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, n (%) | 69 (12) | 42 (11) | 27 (13) | 0.476 |

| Brachial pulse pressure >65 mmHg, n (%) | 222 (38) | 118 (31) | 104 (51) | <0.001* |

| Moderate-to-severe WMH, n (%) | 165 (28) | 78 (21) | 87 (42) | <0.001* |

| Cerebral microbleeds, n (%) | 62 (11) | 30 (8) | 32 (16) | 0.004* |

| Silent or overt lacunes, n (%) | 62 (11) | 24 (6) | 38 (19) | <0.001* |

| >10 enlarged BG-PVS, n (%) | 177 (30) | 80 (21) | 97 (47) | <0.001* |

| Other (non-lacunar) stroke subtypes, n (%) | 33 (6) | 11 (3) | 22 (11) | <0.001* |

*Statistically significant result; ‡ Inverse significant result; WMH: white matter hyperintensities; BG-PVS: basal ganglia-perivascular spaces.

Also, in univariate analyses, severe tooth loss was significantly associated with ICAD (OR: 1.73; 95% C.I.: 1.23 - 2.44; p=0.002). The significance between severe tooth loss and ICAD persisted when age and sex were added to the model (OR: 1.44; 95% C.I.: 1.01 - 2.06; p=0.047). However, the odds of ICAD increased slowly and non-significantly until age 70, and then rapidly climbed in a non-linear fashion. We then converted age into a binary variable divided at the median (69 years), so that the non-linear association between age and the odds of ICAD could be appropriately analyzed. Using backwards elimination to create the most parsimonious model, severe tooth loss remained significantly associated with ICAD in the model that also included age (partitioned by the median) and other significant covariates, as well as in a model that excluded age as a covariate (Table 3)(Table 4)(Table 5). Interaction models and mediation analysis showed no interaction or effect modification of age in the association between severe tooth loss and ICAD (data not shown).

Table 3 Parsimonious logistic regression models (with variables reaching p<0.1 significance in the fully-adjusted model) fitted to assess the independent association between severe tooth loss and intracranial atherosclerotic disease (as the dependent variable).

| Model including age as a continuous variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | |

| Severe tooth loss | 1.41 | 0.96 - 2.06 | 0.077 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.04 | 1.01 - 1.06 | 0.003* |

| Poor body mass index | 0.68 | 0.44 - 1.06 | 0.089 |

| High glucose | 2.24 | 1.55 - 3.34 | <0.001* |

| Lacunes | 2.20 | 1.21 - 4.01 | 0.010* |

| >10 enlarged BG-PVS | 2.16 | 1.42 - 3.29 | <0.001* |

| Non lacunar strokes | 3.57 | 1.57 - 8.09 | 0.002* |

Table 4 Parsimonious logistic regression models (with variables reaching p<0.1 significance in the fully-adjusted model) fitted to assess the independent association between severe tooth loss and intracranial atherosclerotic disease (as the dependent variable).

| Model with age stratified according to its median value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | |

| Severe tooth loss | 1.46 | 1.00 - 2.13 | 0.050** |

| Age (median) | 1.49 | 1.00 - 2.23 | 0.047* |

| Poor body mass index | 0.68 | 0.43 - 1.06 | 0.085 |

| High glucose | 2.30 | 1.55 - 3.43 | <0.001* |

| Lacunes | 2.19 | 1.19 - 3.99 | 0.011* |

| >10 enlarged BG-PVS | 2.39 | 1.58 - 3.59 | <0.001* |

| Non lacunar strokes | 3.44 | 1.53 - 7.76 | 0.003* |

Table 5 Parsimonious logistic regression models (with variables reaching p<0.1 significance in the fully-adjusted model) fitted to assess the independent association between severe tooth loss and intracranial atherosclerotic disease (as the dependent variable).

| Model excluding age as a covariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | |

| Severe tooth loss | 1.57 | 1.08 - 2.27 | 0.018* |

| Poor body mass index | 0.62 | 0.40 - 0.97 | 0.036* |

| High glucose | 2.26 | 1.52 - 3.35 | <0.001* |

| Lacunes | 2.39 | 1.32 - 4.31 | 0.004* |

| >10 enlarged BG-PVS | 2.60 | 1.74 - 3.89 | <0.001* |

| Non lacunar strokes | 3.55 | 1.58 - 7.97 | 0.002* |

*Statistically significant result; ** Marginal significance; BG-PVS: basal ganglia-perivascular spaces.

DISCUSSION

This population-based study conducted in a cohort of older adults living in rural Ecuador shows that severe tooth loss and increasing age are both associated with the risk for ICAD, but they are also correlated. Due to the fact that older subjects are more likely to have severe tooth loss, some of the effect of tooth loss is captured by age. This explains why the univariate odds ratio of this association (1.73) declines in the most parsimonious adjusted model with age partitioned at the median (1.46). However, that portion of the effect (46% more) is solely due to the severity of tooth loss independent of the effect of increasing age over ICAD.

Non-traumatic tooth loss is a major cause of chronic periodontitis worldwide.(27) Bacteria (often Gram-negative anaerobes) that cause periodontitis may persist for several months after tooth extraction, favoring the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that trigger atherosclerosis.(28)(29) As previously mentioned, inflammation plays a role in all the stages of atherosclerosis, from its onset to the occurrence of thrombotic complications.(12)(13)

Therefore, results of the present study confirm the previously reported association between severe tooth loss and atherosclerosis. The novelty of this study, however, resides in the investigation of the intracranial vascular bed. Indeed, investigation on the association between severe tooth loss and ICAD is limited. A PubMED search (up to March 22, 2020), using the combined key words “tooth loss”, “periodontitis”, “periodontal”, and “intracranial atherosclerosis”, disclosed only eight articles,(30) but none of them focused on ICAD. In only one study, the authors assessed the progression of stenosis of extracranial carotid arteries in relation to tooth loss and poor oral hygiene, and found a positive relationship.(31) While both extracranial carotid atherosclerosis and ICAD may coexist,(32) it has been documented that they may result from different risk factors.(33)(34) Therefore, the association between tooth loss and extracranial atherosclerosis (demonstrated in the above-mentioned study(31)) does not necessarily imply that tooth loss is associated with ICAD. The present study provides new evidence of the association between severe tooth loss and ICAD, as well as the importance of increasing age on this association.

Limited access to oral health care and lack of awareness of the consequences of missing teeth may be one of the factors responsible for the increasing prevalence of stroke in older adults living in remote rural settings.(35) Epidemiologic surveys assessing the prevalence of severe tooth loss and its cerebrovascular correlates may allow the implementation of cost-effective strategies directed to reduce their burden in these regions.

The present study has some limitations that go beyond its cross-sectional design, which does not allow for causal conclusions. Nevertheless, biological plausibility suggests that the direction of the relationship goes from severe tooth loss to ICAD, since reverse causation is unlikely. The study population is limited to individuals of Amerindian ancestry living in remote rural settings, and our findings may not be generalizable to other races/ethnic groups or populations living in urban centers. It is also possible that some unmeasured biomarkers (particularly inflammatory cytokines) are in the path of the association between severe tooth loss and ICAD. In addition, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of our subjects with severe tooth loss who currently do not have ICAD, may develop this condition in the future. On the other hand, the population-based design with unbiased recruitment of study participants, and the systematic assessment of tooth loss, calcium content in the carotid siphons and stenosis of major intracranial arteries by means of standard and internationally accepted methods, all argue for the validity of our findings and represent major strengths of the present study. Another advantage of the present study is the paucity of current or past smokers in the study population, which reduces the potential confounding effect of smoking on the association between severe tooth loss and ICAD.(36)(37)

In summary, the present study suggests that severe tooth loss is associated with ICAD in older adults and that age plays a role in this association. Further longitudinal studies, which should also include the assessment of other atherosclerosis biomarkers, are needed to confirm these findings.