Introduction

Human beings are not capable of development without the support of a primary caregiver or protector figures(1) neither without closer and affective relationships with meaning people(2)(3). These statements corroborate Bowlby’s proposal(4) who formulates the attachment theory as a highly organized system(5) which has a fundamental basis the need to feel security and to facilitate the adaptation. According to Olza(6), attachment is a bond between mother and son/daughter that guarantees his/her survival, because the mother offers a secure base, thus, the child is capable to explore the world by himself(7). Children’s attachment behavior is learned and reinforced by the mother or the primary caregiver, generating an attachment style between the children and the adult with a variety of consequences(3), ideas that nowadays have become a target of attention for the Latin American context(8).

Mother works as an auxiliary cortex(9) because it facilitates an interactive regulation through the stimulation of specific cerebral zones, especially those related to memory(10). This relationship allows children to learn through the conformation of mental representations(11), making possible a behavior's organization(12) and addressing affection responses with the ones that correspond to child’s needs(13).

Three attachment styles that have been proposed(7). The first one, secure attachment, is in charge of creating a level of neurophysiological homeostasis and its absence would bring alterations in the nervous system(!4). People with this attachment style is capable of establishing a mutual secure dependence. In this sense, their relationships are felt as satisfactory and stable(2), being competent in social and emotional areas(6), expressing their feelings openly, are friendly and trustable, showing themselves as cooperative, empathic and interested in learning(3). On the other hand, their mothers are described as sensitive and available(7), creating what has been denominated as interactive synchrony(15).

The second attachment style is avoidant/insecure, people presenting this attachment style show difficulty in interpersonal relationships, with avoidant behavior of closeness and emotional implication(7). From their childhood, these people understood that they are not supported by their primary caregiver, explaining why they show indifference as a form of defensive reaction since they had suffered rejection in their entire life. Thus, they deny their needs preventing frustration feelings(2). Their mothers ignore their signals, learning that it is not available when they need her, not depending on her and becoming self-sufficient(7).

The third attachment style is insecure ambivalent. These people show difficulties in personal relationships, presenting ambivalent behavior of irritation and contact resistance(7). They also possess a great need of contact and intimacy, but at the same time, are afraid of losing the bond, generating contradiction among the wish of closeness and the fear of failing(2). Their mothers behave incongruently: sometimes they are very careful and, in others, they ignore or reject their child’s efforts to be close to her, determining a level of unpredictable responses(5). Thus, children show themselves as very dependent, being not able to achieve their developmental tasks(7).

The primary caregiver and his/her child make up a relationship that is transformed in an interpersonal schema(16). This is recorded on the cerebral inferior levels and maintained as a somatosensory footprint that conditions automatically the way of creating relationships where consciousness are not able to access. This theme has been evidenced by Soon, Braas and Haynes(17) who also recognized that the most advance cognitive processing is achieved later, when the information reaches the neo-cortex(9), being influenced by hormonal aspects too(6).

In this line of argumentation, Cozolino(18) addressed that a good quality of attachment, continuous and lasting in time, is essential for psychological and emotional health, with the presence of a variety of tools to face difficulties. Secure attachment has been linked with brain’s physiological maturity(19), self-image(20), the capacity of affective regulation(21), internalized representations that organize and influence in the behavior with others(22), cognitive capacities and self-esteem(23). Thus, the quality of attachment allows us to predict emotional and relationship processes in adolescence and early adulthood (university stage), presenting consequences in the levels of cognitive and affective autoregulation are altered, overall in ambivalent and avoidant adolescents who tend to have major emotional disorders(7).

Bowlby(4) highlighted the impact of attachment in the regulation with the contact of other people and some cognitive problems, as well as the evolutionary representation of the self and others. There is evidence of the relationship of secure attachment with major emotional stability, not doubts this influences in the development of the intra- and inter-personal regulation with effects over the learning process and academic performance in university(24)(25).

At the same time, it has been established that different types of attachment influence the social development in early childhood and has direct effects in adolescence and adulthood. For example, insecure attachment has been linked with psychopathologic symptomatology(26), such as depression(27), substances abuse(28), among other disorders that impact negatively into adult’s psychic life.

Other studies(14) have demonstrated the importance that primary attachment system’s functions have, as well as the possibility of mentalization facilitated by the relationships with others(21)(29). In this same line of research, it has been found that attachment is fundamental for affective and cognitive human being’s performance(22). There is a strong relationship among emotional attachment and brain structures implicated in the information processing (action systems)(30), which is produced by external continuous regulation(20) that is contributed by interpersonal relationships(31).

Brain processing is reached easily when experiences of relationships are acquired in a stable and secure environment; oppositely, when a person perceives a situation as threatening, response circuits are activated automatically(14), affecting behavior and cognitive performance. Therefore, Godbut, Daspe, Runts, & Cyr(32) found a direct relationship among parental maltreatment in childhood, ambivalent attachment style and borderline personality disorder's symptoms. Also, the relationship among insecure attachment and children presenting attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder has been studied, although, results are not conclusive yet(33).

Studies about attachment styles in survivors of sexual abuse in childhood contribute with evidence for the development of an attachment style high in anxiety or avoidant, and presenting sexual compulsion or avoiding sexual contact(34). Instead, a negative relationship was found between insecure attachment and relationship satisfaction(35). Nowadays a technological era is taking over, attachment styles have also been studied in the relationship with internet addiction(36).

The first methodologic proposal to assess attachment was realized experimentally, through what Ainsworth(37) denominated the stranger situation. This allowed them to determine the child's attachment style through the exposure to three situations: (a) being accompanied by child’s primary caregiver, (b) being accompanied by child’s primary caregiver and the presence of a strange person, and (c) being accompanied only by a strange person.

A diversity of instruments with adequate psychometric properties to assess attachment have been developed. For example, the classical scale Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) (11)(7), in the United Kingdom was developed a brief scale to assess childhood attachment(38) and others to assess the attachment style in the context of rehabilitation of patients with neurological damage(39). In Denmark, the scale of emotional development for children and adolescents(40), in Italy the scale MDS-16 to assess reveries based in the attachment theory was proposed(41), in Canada, a scale to explore childhood abuse and insecure attachment(34), as well as the scale to assess attachment in preschoolers were elaborated(42).

From the systematization and revision realized is possible to conclude the next: (a) attachment assessment is a part of a line of research that stills in development, (b) there is an absence of scales to assess the adult attachment that have been developed and validated in Latin America, (c) many of the proposals to assess attachment are based in the deficit or its value negatively and, (d) there is no free access to the content from Latin American context.

Considering these elements is of great interest for the research team to contribute with the appreciation of this construct that is still in development as a promising line of research. Therefore, the objective proposed in the present study was to develop a scale for assessing attachment (AP-1) that considers theoretical classic postulates, that is free to access, with an adequate linguistic content for its application in Chile and Ecuador, as well as in the Latin American context and which is self-reported and focuses in adult population.

Hypotheses analyzed in this study were:

(a) The AP-1 scale will have adequate values of internal consistency and will be minimal to none item’s elimination to achieve its reliability.

(b) Concurrent validity of the AP-1 scale will be significant when correlated with a scale assessing a similar psychological construct.

(c) The exploratory factor analysis of the AP-1 scale will allow maintaining item’s organization proposed in its starting development.

(d) The confirmatory factor analysis of the AP-1 will have an adequate solution of three factors: (a) secure attachment, (b) avoidant attachment, (c) ambivalent attachment.

Method

Sample

This study was realized in the Latin American context, in Ecuador and Chile, the total sample was of 1563 participants aged between 17 and 33 years. The sample from Chile was of 728 participants, protocols that were not entirely completed, with double responses or any kind of inconsistency were eliminated, finally 713 protocols were taking into account for this study. In terms of gender 335 (47%) of the participants were females and 378 (53%) were males. According to the age, the mean was 20.27 years (SD = 2.5). According to marital status, 692 (97.1%) were single, 9 (1.3%) were married and 12 (1.7%) were living together. Referencing to secondary school of precedence, 69 (9.7%) were from private school and 644 (90.3%) were from the municipal system of education.

In Ecuador, the total of applied protocols were 835, those that were not entirely completed or with any inconsistency were eliminated, taking as valid 804 protocols for the statistical analysis. In terms of gender 526 (65.4%) of the participants were females and 278 (34.6%) were males. The age was between 17 and 33 years (M age = 20.79, SD = 2.21). According to marital status, 789 (98.13%) were single, 19 (2.4%) were married, 4 (.5%) were living together and 2 (.2%) were divorced. Referencing to secondary school of precedence, 590 (73.4%) were from the private school, 161 (20%) from public schools, 6.3% from municipal schools and 2 (.2%) were from public-municipal schools.

Instruments

Attachment Scale AP-1

For the development of the Scale AP-1, we took as base Bowlby's4 classical theory, adding the clinical expertise and the diary interaction with university students; the attachment styles considered were secure, avoidant and ambivalent, the disorganized one was not acknowledged, because this style produces many difficulties to whom presents it and probably is not cursing university studies.

For each attachment style, its main characteristics were studied and described, following the proposal of the items with a positive formulation and oriented towards ability. In this sense, it will allow a better comprehension of them for the participants. In table 1, each of the proposed items with its theoretical argumentation is presented. (Table 1)

Table 1 Attachment Scale and theoretical argumentation for each item

| Item | Item’s Theoretical Argumentation |

| 1. I show empathy in my social relationships. | Empathy is a very important aspect in the relationship mother- son/daughter, guiding the conformation of secure attachment. |

| 2. Is easy for me to make new friends. | Secure attachment allows people to show themselves as calm, trusted and secure when establishing social relationships, and this fact makes easier to stablish them. |

| 3. I am open to trust in other people. | Trust is the base for an interpersonal secure relationship, which guides secure attachment as well. . |

| 4. When I’m in trouble, I’m able to ask for help to other people. | Children with secure attachment perceive their mother as a “secure base” to whom they could come up to when they are struggling. So, secure attachment stimulates a person’s capacity to ask for help when needing. |

| 5. When I’m in someone’s company, I tend to trust that person. | Secure attachment constitutes the base for stablishing trust relationships, that is why a person tends to naturally trust in the people around them. |

| 6. I tend to reject social relationships that imply compromise. | Avoidant attachment is related to rejection in the contact and the emotional implication with other people. |

| 7. I tend to show indifference in the face of important situations that are important in my life. | An avoidant attachment’s characteristic is the indifference. People with this style of attachment tend to show this response in front of a situation of his/her environment, and this does not mean that it does not affect them. |

| 8. It is hard for me to understand another’s living situation. | It is well known that the avoidant attachment, ambivalent and disorganized are related to different levels of difficulties in the mentalization, it means, the capacity to understand another’s experiencing feelings. |

| 9. I show myself as an independent person daily, even when it is not like this. | A person with avoidant attachment tends to show a high level of independence and and self-sufficiency, since there is a previous experience of not counting with their mother as a secure base. |

| 10. I fell worried when I’m apart of people that is important for me. | A strong reaction in front of a separation implies difficulties in trusting and security, related with ambivalent attachment. |

| 11. Is difficult to me to make decisions. | An ambivalent attachment’s characteristic is the difficulty to make decisions, because of the increase of anxiety when choosing for an option. |

| 12. It is difficult for me to stablish social contact. | Ambivalent attachment is characterized for difficulties to stablish and maintain social contact, because of the high levels of anxiety. |

| 13. I consider myself as an insecure person. | The difficulty in social relationships, is reverted towards themselves and their self-image, this explains that a person with an ambivalent attachment perceives themselves as insecure. |

| 14. I feel calm when I’m alone. | A person with secure attachment feels calm being alone or with others. |

Sense of Coherence Scale SOC-15

To assess discriminant validity of the Attachment scale AP-1 there was applied the scale SOC-15(43), this scale assesses the classical three factors that set this construct: comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. In this scale, items such as “when I express my feelings, I think that everyone else understands me” or “things that I do in my life makes sense” are proposed. Previous investigation has shown adequate reliability of this instrument.

Procedure

This investigation started once obtaining approval from the Ethical Committee for the research with human beings (code 2019-58-EO). After it, a collaborative job was executed to prepare the scale's items, it was possible through video conference between researchers from Chile and Ecuador.

When the first version of the scale was done, five cognitive interviews to improve the understanding of proposed items were conducted in both South American countries simultaneously. Then, a pilot study in a sample of 10 university students participating was applied, obtaining some observations that were taken into account to get the best and final version of the scale.

Before employing the instruments, authorizations to apply them massively were managed at universities from Chile and Ecuador, asking for the collaboration of authorities and professors by explaining the objectives and aims of the present research. Students were then invited to voluntarily participate in this study. They had the opportunity to read the informed consent, in which the research objective, lasting time, directions to respond to the instruments and confidentiality compromises of the obtained data and results were explained. Through signing this informed consent, they accepted their volunteer participation and the comprehension of the research. The application was realized collectively in the same classrooms where they were, under the direction of a researcher belonging to the team.

Once the information from Chile and Ecuador was obtained, databases were built. Statistical analyses using SPSS version 25 and AMOS version 23 software, and results were discussed by every member of the research team.

Data Analyses

For the sociodemographic data, statistical descriptive analyses such as central tendency and dispersion were used. To analyze the four hypotheses there were different procedures performed. For the first hypothesis, the Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega; for the second hypothesis, a Pearson’s correlation; for the third hypothesis, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA); and in the fourth hypothesis, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Results

Results are presented according to hypotheses proposed in this research, as following:

Hypothesis 1: Scale’s Internal Consistency

For each attachment’s subscale, there were two calculations of internal consistency applied. The first one, using the procedure of Cronbach’s Alpha and the second one with the McDonald’s Omega, based on the item’s factor loading to its respective subscale.

Maintaining the hypothetical setting of the Secure Attachment subscale, with its items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 14, a Cronbach’s Alpha consistency of .63 and .62 was obtained and with McDonald’s Omega .77 and .75 in Chile and Ecuador respectively. Then, the omitable items that would improve the scale's condition were evaluated. In Chile, it was found that items 1 and 14 did not correlate statistically significant with the rest of the items (between r = -.02 and -.08, p = > .05); in Ecuador the same occurred with item 14 (r = - .13, p = > .05). As a consequence, those items were eliminated, achieving an improvement in the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of .75 and .72 and McDonald’s Omega of .80 and .82.

In the second subscale, Avoidant Attachment it was started by analyzing the hypothesized distribution made by the research team, where item 6, 7, 8 and 9 were considered as setting. A Cronbach’s Alpha of .51 and .63 was found and a McDonald’s Omega of .60 and .73. The correlation among the items was between r = .21 and .26, and .17 and .30, p = <.05, being the item 9 which presented a minor level of correlation in Ecuador’s sample. When revising this setting it was determined that the elimination of an item would not improve the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient neither in Chile nor Ecuador; although, when going back through each item’s factorial loadings it was found that the item number 9 loaded the lowest (in concordance with the correlation). Once it was eliminated, internal consistency was recalculated through McDonald’s Omega procedure, finding a better result of .60 and .75.

In the third subscale which assessed Ambivalent Attachment with the items 10, 11, 12, and 13 it was found a Cronbach’s Alpha of .64 and .67, and a McDonald’s Omega of .70 and .77. The correlation among the items was between r = .19 and .47, being the item 10 which contributed to less in Ecuador and Chile. Because of it, this item was eliminated obtaining a modification in the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of .68 and .72 and a McDonald’s Omega of .68 and .75.

The instrument was analyzed with the whole sample from Chile and Ecuador and it was found that in Secure Attachment (items 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of .73 and McDonald’s Omega of .82. In Avoidant Attachment (items 6, 7, 8 and 9) a Cronbach’s Alpha of .58 and McDonald’s Omega of .70. In Ambivalent Attachment (items 11, 12 and 13 a Cronbach’s Alpha of .69 and McDonald’s Omega of .73.

Internal consistency results contribute with empiric evidence in favor of its proposed setting, since the three subscales proposed to measure the attachment’s constructs count with acceptable reliability parameters.

Hypothesis 2: Convergent Validity

This hypothesis was analyzed through the correlation of the three variables of attachment measured with the developed scale and other variables of a similar theoretical construct, which is the Sense of Coherence. This was assessed with the scale SOC-15, which is configured by three indicator identified as comprehensibility (α = .72 Chile, .67 Ecuador and .70 total sample), manageability (α = .81 in Chile, .78 in Ecuador and .80 in the total sample), and meaningfulness (α = .80 in Chile, .83 in Ecuador and .80 in the total sample). Table 2 presents descriptive data. (Table 2)

Table 2 Descriptive data of measures realized in the two countries.

| Chile | Ecuador | Total Sample | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Secure Attachment | 13.93 | 3.33 | 17.70 | 3.79 | 18.07 | 3.69 |

| Avoidant Attachment | 7.00 | 2.70 | 10.41 | 3.40 | 9.95 | 3.41 |

| Ambivalent Attachment | 7.86 | 3.04 | 7.87 | 3.05 | 7.86 | 3.03 |

| Comprehensibility | 20.64 | 3.16 | 19.92 | 3.21 | 20.28 | 3.19 |

| Manageability, | 13.06 | 3.79 | 19.05 | 3.66 | 19.40 | 3.73 |

| Meaningfulness | 16.56 | 2.87 | 20.33 | 3.65 | 16.32 | 2.94 |

In Chile, secure attachment showed a direct proportional correlation with comprehensibility and meaningfulness with a level between r = .36 and .46, p = < .001, meanwhile, with manageability showed an inversely proportional correlation r = - .09 p = .02. Avoidant Attachment showed an inversely proportional correlation with comprehensibility and meaningfulness at a level among r = -.22 and -.29, p = <.001. Meanwhile, with manageability it showed a directly proportional correlation with a level among r = .86, p = < .001. In the Ambivalent Attachment it was found inversely proportional relationships with comprehensibility and meaningfulness with a level among r = - .41 and - .42, p = <.001, meanwhile, with manageability obtained a directly proportional correlation r = .45, p = <.001.

In Ecuador, the correlation analysis found that secure attachment correlated directly proportional and statistically significant (p = < .001) with comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness among r = .30 and .37. Avoidant Attachment correlated inversely proportional and statistically significant (p = < .001) with the three variables of sense of coherence in a level among r = - .14 and -.17. Ambivalent Attachment correlated inversely proportional and statistically significant (p = < .001) with the three variables described in a level among r = -.29 and -. 34.

With the total sample, it was found that directly proportional correlations among secure attachment and comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness in a level among r = .34 and .43, p = < .001. In the Avoidant Attachment it was found that inversely proportional correlations with the three variables of sense of coherence in a level among r = -.26 and -.27, p = < .001, as well as with Ambivalent Attachment, with correlations among r = -.35 and -.42, p = < .001.

Hypothesis 3: Exploratory Factor Analysis

At first, the Barlett’s sphericity test was applied. In Chile it was found a value of KMO = .75, x 2 = 1989.16, p = < .001; in Ecuador KMO = .77, x 2 = 2496.81, p = < .001, and in the total sample a KMO = .77, x 2 = 4133.91, p = < .001. These results suggest that the scale counts with the necessary condition to apply the exploratory factor analysis. In table 3 the items’ organization and its loading factor through the method of extraction of principal components and a Varimax rotation with a Kaiser normalization is presented. (Table 3)

Table 3 Item’s factorial loading and its factor organization

| Ecuador | Chile | Total sample | |||||||||||||

| Factors | Factors | Factors | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| A1 | .64 | -.09 | -.20 | .07 | .14 | -.37 | .25 | -.63 | .18 | .54 | .01 | -.39 | .15 | ||

| A2 | .64 | -.40 | .17 | -.18 | .43 | -.71 | .15 | -.01 | .01 | .68 | -.32 | .08 | -.17 | ||

| A3 | .73 | -.01 | .16 | -.25 | .83 | -.18 | -.01 | -.01 | -.04 | .76 | -.02 | .09 | -.14 | ||

| A4 | .70 | .06 | .02 | .12 | .72 | -.14 | .01 | -.01 | .04 | .68 | .02 | .04 | .07 | ||

| A5 | .75 | .09 | .01 | .02 | .82 | .04 | .02 | -.15 | -.04 | .74 | .11 | -.07 | .03 | ||

| A6 | .04 | .03 | .67 | .07 | -.08 | -.04 | .31 | .36 | .56 | .06 | .09 | .60 | .24 | ||

| A7 | -.01 | .08 | .77 | -.01 | -.07 | -.02 | .27 | .57 | .16 | -.01 | .10 | .70 | -.01 | ||

| A8 | -.01 | .29 | .67 | -.03 | .01 | .06 | .03 | .76 | .01 | -.04 | .16 | .71 | -.09 | ||

| A9 | .02 | .57 | .40 | .04 | -.09 | .20 | .59 | .33 | -.09 | -.02 | .56 | .40 | -.09 | ||

| A10 | .28 | .60 | -.12 | .07 | .06 | -.05 | .74 | -.09 | -.05 | .24 | .60 | -.09 | -.04 | ||

| A11 | -.01 | .73 | .21 | -.20 | .06 | .41 | .61 | .12 | .12 | .01 | .73 | .21 | -.06 | ||

| A12 | -.34 | .66 | .18 | .13 | -.11 | .74 | .19 | .20 | .13 | -.37 | .59 | .24 | .18 | ||

| A13 | -.10 | .74 | .11 | .09 | .01 | .64 | .46 | .02 | .07 | -.13 | .75 | .08 | .12 | ||

| A14 | -.03 | .06 | .07 | .95 | .02 | .16 | -.20 | -.11 | .83 | -.03 | .01 | .04 | .93 |

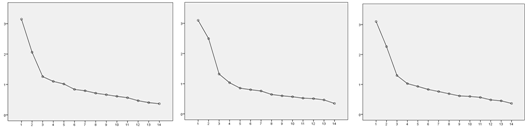

In figure 1 a sedimentation graph is presented, where it is possible to identify the number of factors that emerge in the scale to assess attachment. (Figure 1)

According to the exploratory factor analysis realized, the solution that fits the best to the model is coherent with the hypothesis. With the three factors of attachment, secure, avoidant and ambivalent it is possible to explain the 41.61% of variance in Chile, 49.17% in Ecuador and a 47.59% in the total sample.

Hypothesis 4: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The confirmatory factor analysis was realized through the method of maximum plausibility and it was considered as goodness-of-fit parameters, the values of comparative fit index (CFI) greater than a .90, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than .07 and a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) less than .08(44). In figure 2 the hypothesized model for the Attachment scale is presented. (Figure 2)

Figure 2 Hypothesized model tested in the confirmatory factor analysis for Chile, Ecuador and the total sample.

This model considered the initial scale proposal, leaving behind the items 9, 10 and 14 since these did not contribute to internal consistency. Goodness-of-fit parameters found were the following: in Chile: x 2 (41) = 376.38, p = <.001, SRMR = .08, CFI = .78 and RMSEA = .10 (.09 - .11). In Ecuador: x 2 (41) = 368.91, p = <.001, SRMR = .0745, CFI = .824 and RMSEA = .10 (.09 - .109), and in the total sample: x 2 (41) = 717.03, p = <.001, SRMR = .077, CFI = .80 and RMSEA = .10 (.09 - .11).

The hypothesized model was tested with parameters in favor of its internal consistency and did not obtain the adequate fit. Because of it, factor loading of each item was reviewed in the exploratory factor analysis, finding that the two first items of the secure attachment scale were the ones that contributed the less to the factor, which is why those were deleted. In figure 3 the second factorial hypothesized structure is presented. (Figure 3)

Figure 3 Second model tested through confirmatory factor analysis in Chile, Ecuador and the total sample.

The second hypothesized model found an adequate goodness-of-fit which suggested that each subscale would be set by three items. Parameters of model’s goodness-of-fit were in Chile x 2 (24) = 64.53, p = <.001, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .06 (0.04 - 0.75) and SRMR = .043. In Ecuador x 2 (24) = 88.63, p = <.001, CFI = .967, RMSEA = .04 (0.03 - 0.60) and SRMR = .03 and with the total sample: x 2 (24) = 136.28, p = <.001, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05 (0.04 - 0.65) and SRMR = .03.

Discussion

This research has reported the development and psychometric analysis of a scale to assess the adult attachment in two Latin American countries: Chile and Ecuador. Contributing like this in an aspect not yet solved in the line of research of adult attachment, which is its assessment methods. To achieve this objective, four hypotheses to search about internal consistency in terms of reliability and convergent validity of the construct were proposed.

The first hypothesis proposed that internal consistency’s values would be adequate. Due to the favorable results obtained, the values generated are within acceptable parameters, affirming this hypothesis. Furthermore, a minimum items’ elimination was made to improve internal consistency values.

Therefore, it was convenient to remove item 10 from the ambivalent attachment subscale, and the item number 14 from the secure attachment subscale. This is because these influenced negatively to the scale’s reliability; their elimination improved its value. Statistical findings were confirmed by theory, since the analysis determined that these items were linguistically formulated, considering an emotional aspect, using the statement “I feel”. This formulation diverged completely from the other chosen items that referred to behavioral aspects, which can be directly and externally observed. This brought the thought that feelings are subjective, and because of it, evaluating them represents more difficulties. Taking into account that during the attachment development in childhood, mother’s behavioral response to son/daughter’s needs4 is the one that determines the unfolding of affective synchronicity.

It is possible to estimate a modification on item 6 that refers to a plausible rejection to a social relationships compromise. This could create difficulties in a person's position towards a relationship, because a compromise is not necessary to get involved in every social relationship. For example, a behavior of courtesy does not necessarily imply a compromise; meanwhile, affective relationships demand a compromise. This would contribute to the easy and clear position of a person towards the relationship.

The second hypothesis proposed that the scale developed would have an adequate concurrent validity when correlated with others assessing the sense of coherence. Findings in this research contribute with empiric evidence in favor of this proposal since the three styles of attachment correlated with the sub-dimensions of meaningfulness, comprehensibility, and manageability of the sense of coherence.

These results are coherent with previous research where it has been reported that attachment styles have been assessed through scales that correlated significantly with the elements that conform the sense of coherence. Also, data is in concordance with other studies where attachment has been related to another theoretical construct such as sense of coherence and resilience(45), emotional regulation(46)(47), self-esteem, physical health(48), romantic relationships and pro-social behavior(49). These among the others that allow understanding attachment relationship with human beings’ diverse psychic characteristics.

The third hypothesis stated that the exploratory factor analysis would keep the items’ organization proposed at first. In this sense, findings contribute to the affirmation of this hypothesis, since most of the proposed items contributed positively to the three factors suggested by the research team.

Items 9, 10 and 14 presented a low factor loading, this was coherent with the other analyses. This data could be explained because of the difference in its linguistic content. This is because the rest of the items are oriented towards an attachment’s behavioral component assessment through daily life routine that might be interpreted easily and valued by a person who fills up the scale. This is different of items 9, 10 and 14 that contain complex aspects within human’s subjectivity (independence or worrying), this gives light to understand its low contribution in the entire scale.

The fourth hypothesis proposed in the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of de attachment scale (AP-1) would have an adequate solution of three factors: (a) secure attachment, (b) avoidant attachment, (c) ambivalent attachment. The analysis conducted allows to support the three-factorial structure of the proposed scale, showing a good-fit of the observed data; obtained results highlight that the scale presents an adequate factorial solution with three sub-dimensions, each of those composed by three items. Because of it, this instrument could become a brief scale to assess adult attachment. Just as many other instruments that count with a similar number of items(38).

Furthermore, the data of the ratified structure in the confirmatory factor analysis are in concordance with previous research that has reported that attachment scales presented adequate psychometric properties with goodness-of-fit indexes appropriated for the three factors (secure, avoidant, ambivalent). This explains a great percentage of the variance in this construct(50) and with theoretical classic bases that considers these three attachment styles as its essential construction(4).

Likewise, obtained results from confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the attachment scale (AP-1) allows preliminarily its usage in the adult population in Chile and Ecuador. This constitutes a significant advance in the assessment of this construct with aims in clinical and psychological investigation in Latin America, improving previous research and scales’ limitations that measured this construct(51)(52).

As conclusion of the realized work, the scale AP-1 presents adequate levels of validity and reliability to assess a young adult’s attachment of Latin American context. Because of it, reported results of this investigation constitutes a valuable contribution to attachment’s assessment instruments. Also, at the same time constitutes one of the developing aspects in this line of research.

Validation of instruments like this reflects an advance in the attachment theory in Chile and Ecuador, because it might be applied in the clinical area and will be valuable in its use to assess attachment in young adults. This in turn will contribute to the comprehension of their actions and responses facing meaningful relationships in their lives.

It is important to highlight that the validation of this scale opens interesting perspectives for future research, because it would be relevant to improve reliability and avoidant attachment sub-dimension’s validity. As well as the application of the scale in other populations in a diversity of contexts to estimate how the instrument conducts.

The limitations of this study that must be declared are related to the subjectivity of human beings which will always be implicit in a self-report scale. This fact might represent a bias of the information given by the participants in their interest to safeguard the ideal image of themselves.

Also, the sample of this investigation belonged to three different cities from Latin America. This explains why data could not be generalized in its totality, although results give a wide idea of attachment behavior in young adults of the countries taken into account for this research. In this sense, this proposed study and obtained results might be projected towards a wider inquiry that must take place in the future. It must consider other Latin American cities in order to get a better explanation of attachment in this region.