INTRODUCTION

The discipline of business history is still a relatively new field in Ecuadorian historiography. While separate studies of the electric power industry in Quito (Núñez and Londoño 2005), the beer industry in Guayaquil (Estrada 2005), foreign companies (Albornoz 2001) and general business histories (Navarro 1976) and (Fierro 1991) have been published, there is still much to be done on the history of individual firms in Ecuador.

A particular case in point is that of the Ecuadorian Corporation, founded in 1913 as a holding company for the subsidiary companies originally developed by the Guayaquil and Quito Railway company. In the histories of the Guayaquil and Quito Railroad, little mention is made of the important role that the railroad played in developing the Ecuadorian Corporation, the first modern holding company (conglomerate), to be established in Ecuador. The purpose of this paper is to present a history of this connection between the Guayaquil and Quito Railway company and the Ecuadorian Corporation.

The theoretical framework for this paper is based on the book The Visible Hand: the Managerial Revolution in American Busines (1977) by Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., the Pulitzer Prize-winning professor of business history at Harvard University. According to Chandler the railroads were the first truly modern business enterprises and the managerial and technological innovations they developed created the framework for the emergence of the modern business corporation.

Chandler’s theory of the connection between the railroads and the modern business corporation is particularly relevant to Ecuador, where the Guayaquil and Quito Railway company and the Ecuadorian Corporation made important contributions to the capitalist modernization of the country. Reference will be made in the course of this paper to the managerial and technological innovations identified by Chandler which are relevant to the process of capitalist modernization of Ecuador, in particular in the areas of administrative structure, finance, construction and the development of the holding company and its subsidiaries.

ELOY ALFARO AND THE LIBERAL REVOLUTION OF 1895

The triumph of General Eloy Alfaro’s Liberal Revolution on June 5, 1895, ushered in a period of radical social and political transformation in Ecuador. The revolutionary period (1895-1912) represented the political triumph of the bourgeois agro-export oligarchy of coastal Ecuador over the conservative highland landlords and the Catholic Church. The principal liberal goals were the secularization of the state, freedom of religion, the elimination of the influence of the Catholic Church in politics and education and the capitalist modernization of the country to attract foreign investment in industry and infrastructure (Ayala, 1983:120).

Alfaro’s top priority was the completion of the railroad from Guayaquil to Quito, the obra redentora, or redemptive work, that in the words of Manuel Chiriboga (1983), constituted the “eje central de la acción estatal en la época liberal. La vinculación regular entre Quito y Guayaquil que uniría todo el país, constituyó la clave de la política modernizadora del Liberalismo” (Chiriboga 1983:96).

For Enrique Ayala (1983) the construction of the Ferrocarril Trasandino should be considered the main accomplishment of Alfaro’s two administrations. One of the main obstacles to the completion of the railroad was the English debt that Ecuador incurred during the wars of independence from Spain. Ecuador had defaulted on the debt and until an arrangement could be made with the English bondholders, it was impossible to arrange a foreign loan to finance the construction of the road.

It was Alfaro’s belief that the railroad could only be built by American engineers and financed by American capital. By 1895 the United States had the largest railway network in the world and the city of New York rivalled London as a financial center. In the fall of 1896 Alfaro commissioned Ecuador’s representative in Washington, Luis Felipe Carbo, to interest New York capitalists in financing and building the road. According to Evermont Hope Norton (cited in Stevens, 1957) a syndicate of 12 New York capitalists was organized in January of 1897. Each member of the syndicate contributed $500 to pay the expenses of Archer Harman, who was selected to secure the concession from the government of Ecuador.

METHODOLOGY

The objective of this essay is to demonstrate the connection between the Guayaquil and Quito Railway Company and the development of the Ecuadorian Corporation, the first holding company (conglomerate) established in Ecuador. The study covers a period of 89 years, from the founding of the Guayaquil and Quito Railway Company in 1897 to the dissolution of the Ecuadorian Corporation in 1986.

The methodology for the present article is a revue of the primary documental sources on the railway company and its subsidiary companies and the Ecuadorian Corporation. The documental research was conducted in the National Archives of the United States in Maryland, the Archivo Nacional de Historia in Quito and the National Archives of Great Britain and Scotland in the following sequence: The primary documental source for the founding of the Guayaquil and Quito Railway Company was obtained from File 422.11/G93 in the National Archives in Maryland.

The documentation on the subsidiary companies of the railroad was obtained from the notarial records in the Archivo Nacional de Historia in Quito. The research on the founding of the Ecuadorian Corporation was carried out in the National Archives of Great Britain. A final trip to the archives of Scotland resulted in the discovery of the original records of the Ecuadorian Association, which helped finance the construction of the Guayaquil and Quito railroad.

The theoretical framework for this paper is based on the book The Visible Hand: the Managerial Revolution in American Business (1977) by Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. who defined the modern business enterprise as having “two specific characteristics: it contains many distinct operating units and is managed by a hierarchy of salaried executives” (Chandler 1977:1).

This management structure was originally developed by the railroads and adopted by the modern business enterprise “to monitor and coordinate the work of the units under its control” (Chandler 1977:3). The Guayaquil and Quito Railway company was the first to introduce this management structure in Ecuador and its eventual adoption by other Ecuadorian businesses represents the railroad’s major contribution to the process of capitalist modernization in Ecuador.

Management by a hierarchy of salaried executives also made possible the development of the holding company, which allowed individual companies to hold stock in other companies, which was the “first essential step in the transformation (…) to the modern industrial enterprise” (Chandler 1977:320). The Guayaquil and Quito Railway company and its successor the Ecuadorian Corporation were the first holding companies established in Ecuador. Based on Chandler’s criteria outlined above, the railroad and the Ecuadorian Corporation must be considered the first modern business enterprises to be developed in Ecuador.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

PART ONE: ARCHER HARMAN: PROMOTER OF THE GUAYAQUIL AND QUITO RAILWAY AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES, 1897 - 1911

Archer Harman (1859-1911) was a man with a wide variety of business experiences before going to Ecuador. As a young man he had worked as a railroad subcontractor in the states of Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana and with a partner built a section of the Colorado Midland Railroad. Harman then moved to Louisville, Kentucky where he worked as a paving contractor and prospected for petroleum. He also speculated in urban real estate and lost a multi-millions dollar law suit in a land speculation deal in eastern Kentucky coal lands.

He then moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where he lost out in a fight for control of a short line railroad between the city of Jacksonville and seaport town of Mayport. Harman then partnered with Edward Morley, who later accompanied him to Ecuador, in a venture to establish a ferry service between the town of Key West and the city of Miami.

To finance this venture Harman engaged in a filibustering expedition to run guns and ammunition to the rebels fighting against Spanish rule in Cuba (Washington Evening Star 1896). Harman’s ship, the City of Richmond, was impounded by the US government and later sold to Henry Flagler, the former partner of John D. Rockefeller. Harman then moved to New York city, where he was invited to join the Ecuador syndicate.

When Harman arrived in Ecuador in March of 1897, Ecuador was in the middle of a period of unprecedented economic prosperity fueled by the so-called auge cacaotero, or cacao boom. Revenue from customs duties and internal taxes increased 2.8 times, from S/.6,932,708 in 1897 to S/.19,545,952 in 1913, the year the Ecuadorian Corporation was founded (Ayala, 1893).

During the same 17 years period cacao production doubled from 358,198 quintals in 1897 to 722,332 quintals in 1913 (Rodríguez, 1992). The future economic prospects of the country looked promising and Harman believed that Ecuador had the resources to pay the interest on the railroad bonds to finance the construction. After intense negotiations the government of Ecuador awarded the concession to Harman and the syndicate on June 14, 1897.

According to Chandler, the heavy capital requirements of railroad construction led to the development of innovative financial instruments, the most important of which were first mortgage bonds and debenture bonds, which were the most common forms of railroad financing in the United States. Both of these instruments were used to finance the construction of the railroad in Ecuador.

The cost of construction was estimated by the syndicate at $17,532,000 in US dollars:

$12,282,000 in first mortgage bonds and $5,250,000 in preferred stock to be issued to the syndicate as their payment for assuming the risk of construction. The concession contract called for a further issue of $7,032,000 of common stock to be divided 49% to the government of Ecuador and 51% to the syndicate, which gave the syndicate the controlling interest in the ownership of the railroad.

But unlike in the United States, where the railroads were privately owned and the interest on the bonds was to be paid for out of earnings of the railroad, the 1897 concession contract obligated the government of Ecuador to guarantee both interest and principal on the bonds. This would become a source of major conflict between the company and the government over ownership of the railroad, resulting in the government’s eventual default on the railroad debt.

According to Deler, the cost of construction was “almost two times the equivalent of the annual expenses of the government at the beginning of the 1890s and six to seven times the average annual amount of custom’s revenues” (Deler 1994:329). The $5,250,000 in preferred stock and the $3,586,320 common stock issued to the syndicate raised the capitalization of the railroad company to $ 8,836,320 US dollars, the equivalent in sucres of S/.17,761,032 at the exchange rate of 2.01 sucres per US dollar. The $12,282,000 bonded debt of the railroad was the equivalent of S/24,686, 820. For the sake of comparison, the total capital in circulation in Guayaquil county in 1909 was S/.42,302,17 (Compañía Guía del Ecuador, 1909).

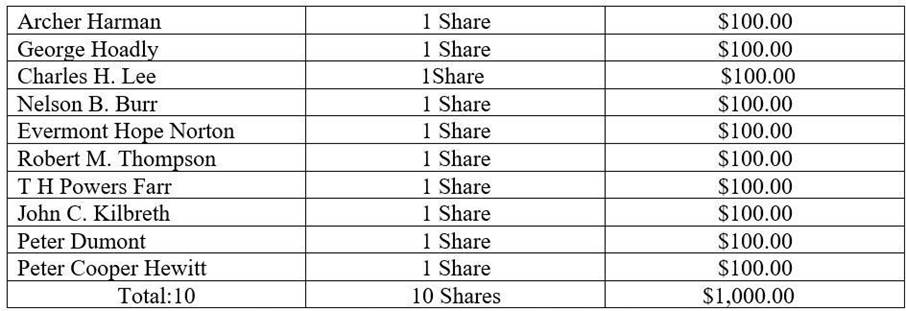

Upon his return to New York Harman reported to the syndicate that the cost of construction was only $5,000,000, a gross miscalculation of the true cost of road (Harman,1897). On September 1, 1897 the Guayaquil and Quito Railroad was incorporated in the state of New Jersey. The subscribers were the following:

Table 1: Incorporators of the Guayaquil and Quito Railway Company

Source: Certificate of Incorporation of the Guayaquil and Quito Railway Company, 1September, 1897, State of New Jersey. Elaborated by Author.

According to Chandler, “legal innovations accompanied financial innovation. To insure legal control over their many properties the railroads perfected the modern holding company” Chandler (1977). But holding companies for manufacturing companies were illegal until 1889, when the state of New Jersey promulgated a holding company law which permitted manufacturing companies to purchase and hold stock in other business enterprises (Chandler, 1977).

The Guayaquil and Quito Railway company was incorporated in New Jersey precisely because of the holding company law and the minimal capitalization requirements for incorporation. From the beginning the Guayaquil and Quito Railway company was interested in much more than just building a railroad, as will be shown in the development of the railroad’s subsidiary companies.

Immediately after incorporating the Guayaquil and Quito Railroad Company Harman left for London to negotiate the purchase of Ecuador’s foreign debt with the Corporation of Foreign Bondholders. A second purpose of Harman’s trip was to secure an underwriter for the first mortgage bonds and place the bonds on the London market. He also presented his project to Lord Revelstoke, the head of Baring Brothers bank, who rejected his proposal. (Baring Archive, 1897- 1898). Harman also failed to place any of the first mortgage bonds on the London bond market.

THE SOUTH AMERICAN RAILWAY CONSTRUCTION COMPANY (SARCCO)

On his return to New York Harman organized the South American Railway Construction Company with a minimum capitalization of $1,000. The subscribers were four members of the original syndicate plus Charles H. Sherrill, a New York lawyer who also drafted the articles of incorporation of the Ecuadorian Association. Article 34 of the 1897 concession allowed the railroad to assign the actual construction to a separate construction company which could in turn subcontract the work.

Two days later, on February 10, 1898 the Guayaquil and Quito Railway company signed a contract with the South American Railway Construction Company to construct the railroad for $4,050,000. A week later the South American Railway Construction offered $4,000,000 to the Drake and Stratton construction company to build the road-a million dollars less than the estimate Harman made in his report to the syndicate, eight million dollars less than the estimated $12,282,000 in first mortgage bonds that the government of Ecuador had agreed to finance! (Cooper-Hewitt, 1898) The contract with Drake and Stratton was signed on March 12, 1898.

Drake and Stratton sent their chief construction engineer George L. Riley to Ecuador in June of 1898 to make a preliminary survey of the line. Riley then cabled that all financial arrangements to construct the line had been finalized. But opposition to the Harman contract had been growingin Ecuador and in September of 1898 congress voted to rescind the Harman concession and Drake and Stratton backed out of their contract (Grito del Pueblo, September 14, 1897).

THE ECUADOR DEVELOPMENT COMPANY

The only funds SARCCO had available beyond the initial capitalization of $1,000 were $650,000 in first mortgage bonds and the $650,000 in preferred stock promised to them, but notyet issued by the Government of Ecuador. Of this amount Harman was to receive $250,000 in bonds and another $250,000 in preferred stock as his commission for obtaining the concession.

Harman returned to London in the summer of 1898 in search of British capitalists to invest in the South American Railway Construction company. While in London Harman made the acquaintance of St. George Lane Fox Pitt, the brother-in-law of Sir John Lubbock, the chairman of the Council of Foreign Bondholders. According to this author (Uggen 2008), Harman was so impressed with Fox Pitt’s aristocratic connections that he sold one half of his interest in the South American Railway Construction Company to Fox Pitt with the condition that Fox Pitt would organize a syndicate in Great Britain to finance the construction in Ecuador. Harman returned to New York in August of 1898 accompanied by Fox Pitt.

On September 16, 1898 Harman, Fox Pitt, Evermont Hope Norton and Thomas Carmichael, the New York representative of the London banking firm of Dent, Palmer and Co. organized the Ecuador Development Company. Dent, Palmer then agreed to underwrite the construction of the road in return for a controlling interest in the company. The Development Company was organized with an authorized capital of only $200,000. The initial subscription was $161,600, of which Dent, Palmer subscribed $73,900 or 47%, giving them a controlling interest in the company.

In August of 1898 the Congress of Ecuador repudiated the 1897 contract with Harman and the Syndicate. According to General Alfaro the 1898 Congress repudiated the Harman contract because it was dominated by enemies of the liberal revolution. But as this article will demonstrate, the Congress had good reason to question the terms of the 1897 concession.

Upon hearing the news of the repudiation of the concession, Harman departed immediately for Ecuador in the company of Fox Pitt and George Mumford, the lawyer for the New York office of Dent Palmer and Co. While in Quito Harman had a falling out with Fox Pitt and Mumford over the amendment of Article 6 of the 1897 concession, which stipulated that the company woud be paid for construction work at the beginning of each mile. But the congress of 1898 modified Article 6 so that the company would only be paid for work completed in the previous month, forcing the company to pay for construction from its own funds.

According to Fox Pitt, “Harman was totally opposed to this change in the 1898 contract but Mumford, as the lawyer for the Development Company, accepted it without Harman’s authorization.” (Uggen 2008). Upon their return to New York Mumford gave an unfavorable report on Harman to Thomas Carmichael, which resulted in Dent, Palmer’s withdrawal from the Development company. After Dent, Palmer’s withdrawal, Harman was once again without funds to finance the construction of the road. Harman then made an arrangement with Evermont Hope Norton to buy out Dent Palmer’s interest in the Development company and transfer the control to the American investors.

THE ECUADORIAN ASSOCIATION

Harman returned to London again in the winter of 1899 where he made the acquaintance of Sir James Sivewright, a wealthy Scotsman who had made his fortune in South Africa. On April 4, 1899 Harman and Sivewright incorporated the Ecuadorian Association in Edinburgh with an initial capitalization of £70,000 pounds. Article 1 of the Memorandum of Association (1899) makes clear that the intentions of the Ecuadorian Association went far beyond that of building the railroad:

. (Ecuadorian Association Ltd. 1899:6)To take, purchase, underwrite, or otherwise acquire and hold any bonds, stocks, obligations and securities of any governments, states, or authorities, supreme, municipal, local or otherwise, and any bonds, debenture stocks, scrip, obligations, shares, stocks, options or other interests, in any trading or manufacturing companies, or companies established for the purposes of any railway, tramway, railway or tramway construction, gas, water, dock, shipping, telegraph, or other undertaking of public utility

On September 6, 1900 Harman and Norton transferred the Ecuadorian Development Company stock, the construction contract, and all the first mortgage bonds and the preferred stock, to the Ecuadorian Association. The stockholders of the Ecuador Development company then exchanged their shares for shares in the Ecuadorian Association.

On June 15, 1900, the Ecuadorian Association assigned the construction contract to the James P. McDonald company of Knoxville, Tennessee, one of the most experienced railroad contracting firms in the United States. The McDonald company was given the section between Chimbo and Alausí, the most difficult and challenging section of the whole line.

On June 8, 1901 the Ecuadorian Association floated an issue of £1,000,000 of 6% Debenture Bonds to raise the capital to finish the line to Quito (New York Times [NYT], 1901). According to Harman, the high cost of construction around the Devil’s Nose resulted in the bankruptcy of the Ecuadorian Association and the dismissal of the McDonald company.

In March of 1904 Archer Harman and his associates, voted to liquidate the Association over the protest of the minority shareholders. To counter their opposition, the minority shareholders were offered the opportunity to exchange their shares in the Association for shares in the Guayaquil and Quito Railway company at the rate of 40% in preferred stock and 60% common stock in the railroad in exchange for every share issued by the Ecuadorian Association.

THE INCA COMPANY

After the Ecuadorian Association was liquidated, Harman organized the Inca Company, with an authorized capital of $150,000 divided into 150 shares of $1,000 each, 149 of which were subscribed by Archer Harman personally (Inca Company Articles of Incorporation, 1904). The Guayaquil and Quito Railroad then assigned the construction contract to the Inca Company, which included the rights to $3,010,000 First Mortgage Bonds and $2,100,000 shares of Preferred Stock for a total compensation of $5,110,000, making the Inca Company (i.e. Archer Harman) the owner of the Guayaquil and Quito Railway Company.

The Inca Company took charge of the construction from the Laguna de Colta to Quito and finished the construction by administration, which meant that construction was carried out by the railroad company and not by the Inca company itself, which was merely a holding company for the stocks and bonds of Archer Harman. This led to a huge conflict between the company and the government, as the railroad charged construction expenses to the operating account, which meant that revenue from operations, that should have been used to pay interest on the bonds, was being used to finish the construction.

Harman claimed that three of the four construction companies were wrecked in the construction of the railroad. This author would argue, on the other hand, that the formation of the separate construction companies were part of an elaborate pyramiding scheme engineered by Harman to transfer the ownership of the railroad to himself.

THE SUBSIDIARY COMPANIES OF THE GUAYAQUIL AND QUITO RAILWAY

Once the rails had reached Guamote, Harman dedicated his time to organizing subsidiary companies to increase the railroad’s earnings. Between 1905 and 1910 Harman organized the following subsidiary companies:

ANGLO FRENCH PACIFIC SYNDICATE

On May 26, 1905 Archer Harman organized in London the Anglo French Pacific Syndicate to purchase 28 acres of prime real estate north of the Ejido Park in Quito. The syndicate contracted Modesto Sánchez Carbo, the manager of the Quito branch of the Banco Comercial y Agrícola to purchase the lands in his name and then transfer the title to the syndicate. Sánchez Carbo was given S/.125,062 by Archer Harman to purchase seven properties between October 23 and November 24 1905.

The syndicate formed the Ciudadela del Centenario in anticipation of the 100 years celebration of Ecuador’s independence from Spain in 1824. On June 1, 1910 the Anglo French Syndicate was liquidated and title to its lands in Quito transferred to the Farms company, a new real estate holding company to hold the title to all of the lands owned by the subsidiary companies of the railroad in Quito and Duran. On March 20, 1920 the Junta del Centenario approved the plans for the urbanization of the Ciudadela del Centenario.

The Farms company then sold the entire property two years later to the Empresa de Mejoras Urbanas of Guayaquil for the sum of S/.450,000. The Empresa de Mejoras Urbanas changed the name to Ciudadela Mariscal Sucre and developed the site which was to become Quito’s modern business district. The Farms retained the title to the 8,000 acre El Recreo property which surrounded the city of Duran.

QUITO ELECTRIC LIGHT AND POWER COMPANY

On November 5, 1905 Harman and Norton organized the Quito Electric Light and Power Company in New Jersey and purchased a controlling interest in La Eléctrica, a small power plant built in 1897 by Manuel Jijón Larrea, Víctor Gangotena Jijón y Francisco Joé Urrutia on the falls of the Machángara river. The Ecuadorian owners of La Eléctrica had run out of fundsand needed fresh capital to expand the plant. The railroad interests supplied the capital and service to Quito was inaugurated on October 8, 1908, only three months after the arrival of the railroad to Quito (El Comercio 1908).

QUITO TRAMWAYS COMPANY

On November 14, 1905 Harman and Norton organized the Quito Tramways company in the state of Delaware and were awarded the franchise to establish tramways service on November 19, 1910. Tramways service was inaugurated on October 8, 1914 to provide transportation from the railroad station in Chimbacalle all the way to the new Avenida Colón, the northern boundary of the tract of land owned by the Anglo French Pacific Syndicate, today Barrio Mariscal Sucre. Unfortunately for the historian, the records of the Quito Tramways company, which were stored in the brewery in Guayaquil, disappeared when la Cervecería Nacional was sold to the Colombian conglomerate Bavaria (Personal communication Jenny Estrada 2004).

THE RECREO COMPANY AND THE NEW GUAYAQUIL LAND COMPANY

On December 5, 1905 Harman organized the Recreo Company in New York to purchase the 8,000 acre Recreo Hacienda from Belisario J. Luque for S/.150,000 ($70,000 in US dollars). The lands of El Recreo surrounded the city of Duran and the land on which the terminal of the railroad was located. Four years later (January 1, 1909) title to the Recreo hacienda was transferred to the New Guayaquil Land Company. Harman’s plan was to develope the Recreo estate and build a “new Guayaquil” to rival the “old Guayaquil” which had been destroyed by the 1896 fire.

To raise the capital to develop the estate Harman travelled to Paris where he interested a large number of small French investors in the project. When the plan failed, the railroad company retained title to the property. The French investors sued Harman in New York and won a judgement of $22,643 against Harman and the railroad (NY Times 1909). But they lost in the Ecuadorian courts and title to El Recreo was retained by the railroad. In recompense the French investors were offered the opportunity to exchange their shares in the New Guayaquil Land Company for equivalent shares in the Ecuadorian Corporation.

THE FARMS COMPANY

On June 1, 1910 Harman and the G and Q board of directors created the Farms Company as a holding company to acquire title to all of the lands owned by the railroad in Ecuador, including the Recreo estate in Durán and the properties purchased by the Anglo French Pacific Syndicatein Quito in 1905. The Farms Company was liquidated in 1922 and title to the Quito and Duran properties were transferred to La Inmobiliaria, another to another real estate holding company, owned by the Ecuadorian Corporation.

THE ECUADOR EXPRESS COMPANY

The Ecuador Express Company was organized on May 1, 1909 to skim off the profit from the freight carried by the railroad, leaving no money to pay interest charges on the first mortgage bonds. The railroad was forced to liquidate the Express Company due to the intense opposition of the Ecuadorian government, which expected the railroad to begin paying its fair share of the interest on the bonded debt once the line began operating between Duran and Quito (El Comercio, 1911).

In 1910 the US State Department, upon request from the Ecuadorian government, published a list of the preferred and common stock holders of the Guayaquil and Quito Railroad Company. The original issue of $12,282,000 was divided in 70,320 common shares and 52,500 preferred shares.

The Inca Company appeared as the owner of 28,629 common shares and 20,331 preferred shares, or a total of 48,960 shares of a par value of $4,896,000, making the Inca Company the largest single shareholder of the railroad. 149 of the 150 shares of the Inca Company were the personal property of Archer Harman, thus making Harman the owner of the majority of the stock of the railroad. (National Archives of the United States, Guayaquil and Quito Railroad File 422.1t1G93/339). Unfortunately for Harman, his stock would not pay interest or dividends until the bonded debt of the railroad had been cancelled.

DEATH OF ARCHER HARMAN, 1911

Ecuadorian opposition to Harman had been building for years and came to a head after it was revealed that he was involved in the negotiations for the sale of the Galapagos islands to the United States. According to Harman’s plan, a portion of the proceeds from the sale were to be used to pay off the bonded debt of the railroad. Archer Harman left Ecuador for New York on April 17, 1911 to discuss the Ecuadorian opposition to the railroad and to him personally with the Department of State. In August, 1911 Harman met with Henry L. Janes, the official in charge of Latin American affairs at the Department.

Harman was presented with a letter from Huntington Wilson, the Assistant Secretary of State, which requested Harman’s immediate resignation as president of the Guayaquil and Quito Railroad and his promise never return to Ecuador. Wilson stated to Harman that “It appears essential that you withdraw from all official connection with the railroad company, which will satisfy the feelings of the Ecuadorians” (Guayaquil and Quito Railway File 422.11G93:346-352). Harman accepted the decision of the State Department under protest and never returned to Ecuador.

Archer Harman died on October 11, 1911 from injuries suffered from falling off his horse while vacationing at the Virginia Hot Springs with his daughter Kate. After Harman’s death his Inca Company shares eventually passed to Archer Harman Jr., the son of Archer’s brother Major John Harman. On April 13, 1925 the Inca Company sold 57,069 shares of a par value of $5,706,900 (28,638 common and 28,431 preferred shares) to the Ecuadorian Government for $600,000. With the sale of the Inca Company stock, the Government of Ecuador became the majority owner of the Guayaquil and Quito Railroad and the Harman family interests in Ecuador and the railroad came to an end.

PART TWO: E H NORTON AND THE ECUADORIAN CORPORATION: 1913-1961

Evermont Hope Norton was named president of the railroad after the resignation of Archer Harman. General Alfaro himself was forced to resign as president on August 11, 1911. Later in the year his supporters staged a revolt in an attempt to return him to power. When the revolt failed Alfaro was arrested and taken to Quito on the same train that he had dedicated his life to build. On January 28, 1912 he was assassinated and his mutilated corpse dragged through the streets of Quito and burned in the Ejido park in the infamous hoguera bárbara.

The burning of Alfaro’s corpse was witnessed by Norton at his residence in the Villa Floresta on Avenida Colombia directly across from the bonfire. According to Norton’s grandson, Presley Norton Yoder (Personal communication November 1, 1989) the brutal death of Alfaro and the opposition to Harman and the railroad convinced Norton that the subsidiary companies could best be protected by separating them from the railroad and re-incorporating them under the laws of Great Britain. On April 19, 1913, Norton founded the Ecuadorian Corporation in London as a holding company to take title to the railroad’s subsidiary companies.

The corporation was capitalized at £1,000,000 pounds sterling, divided into £500,000 common shares and £500,000 in debenture bonds, equivalent to $4,500,000 in US dollars or S/.10,157,400 sucres at the going exchange rate of S/.2.09 to the US dollar, making it the largest corporation in Ecuador at the time. By way of comparison, the two largest Ecuadorian firms in 1913 were the Banco de Pichincha at S/.1,000,000 and the Banco Comercial y Agrícola in Guayaquil at S/. 5,000,000. (Compañía Guía del Ecuador, 1909). In 1913 the total income of the Ecuadorian government from customs duties and internal taxes was S/.19,545,952. (Ayala, 1983).

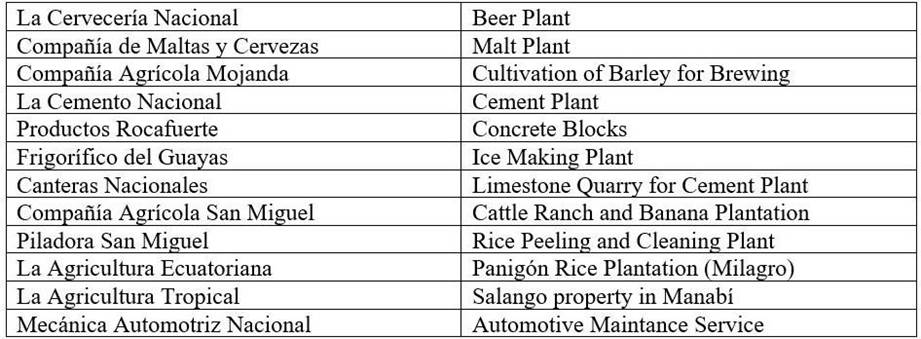

According to the corporation’s prospectus, the following subsidiaries were transferred to the new holding company:

Table 3: Ecuadorian Corporation Prospectus, abril 1913

Source: (The Guardian: abril 24, 1913:14). Elaborated by the Author

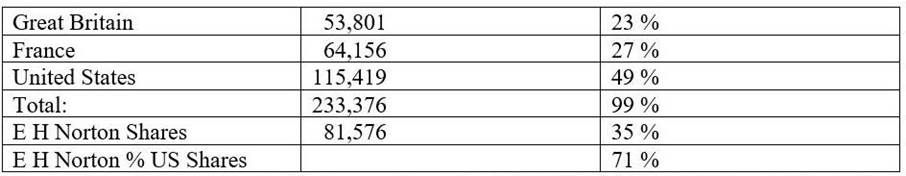

The shares of the Ecuadorian Corporation were divided among British, French and American investors. The 64,156 French shares were transferred by the French investors in the New Guayaquil Land Company. The largest individual investor was E H Norton with 81,576 shares or 35% of the total capital of the Ecuadorian Corporation.

Table 4: Distribution of Ecuadorian Corporation Shares, 1913

Source: Shareholders Ecuadorian Corporation. File: BT31/32153/128446. Elaborated by the Author

When the prospectus of the corporation was published in the press in Ecuador it was attacked ina series of articles in the El Comercio newspaper in Quito. The articles warned of the danger that the Ecuadorian Corporation “trust” posed and the fear that it would create a monopoly which could devour Ecuadorian owned businesses (El Comercio June 8, 1913).

ECUADORIAN CORPORATION ACQUISITIONS, 1913-1938

Barely one month after publishing its prospectus, the Ecuadorian Corporation purchased a two thirds interest in the Fábrica de Hielo y Cerveza (Ice and Beer Factory) from the Guayaquil businessman Enrique Gallardo. The Ecuador Breweries name would later be changed to la Cervecería Nacional, the most profitable of all of the Ecuadorian Corporation’s subsidiaries. (Personal Communication, Carlos Romo Leroux, June 15, 1995).

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914 Ecuador’s cacao exports plummeted. The recovery had just begun when the cacao diseases witches broom and monilla attacked the cacao plantations in 1919. By 1923 cacao production had fallen 30% to 29,564 metric tons. By 1929 cacao production had fallen to 1890 levels, where it stayed for the next 20 years. The effects of the economic crisis sparked the 15th of November 1922 strike of the railroad workers and cacahueros (stevedores employed in Guayaquil in the preparation of the cacao beans for export), followed by the Revolución Juliana of July 9, 1925.

The revolution, led by a group of young military officers from the highlands, offered as an explantion for the coup the domination of the Banco Comercial y Agrícola and the cacao planter elite. When the bank was liquidated the following year, the alliance between the planters, the so- called gran cacao and the Guayaquil bankers, the epoch of the pepa de oro had come to an end. In the coming years the oligarcas del cacao would be replaced by a new oligarchy of sugar and banana planters.

The destruction of the plantations forced many cacao planters into bankruptcy. During the decade of the 1930s many of the planters were forced to sell their properties to settle their debts with the banks. One of the first companies to take advantage of the crisis of the cacao planters was the Ecuadorian Corporation, that purchased three properties in Milagro and Yaguachi: San Miguel (1923), Panigón (1934) and part of the old hacienda Naranjito named Supaypungo (1938).

The name of Supaypungo was changed to Presley Norton, the son of Evermont Hope Norton, the principal stockholder in the Ecuadorian Corpration. The 15,000 acre San Miguel property, located on the outskirts of the city of Milagro, was purchased from the Deutsch Cacao Plantagen, whose principal stockholders were the Seminario brothers. Included in the purchase was the rice processing plant in Milagro.

The corporation developed the property as a successful cattle ranch and rice growing operation on lands that had once been one of the largest cacao plantations in the country. In the same year the Corporation purchased an interest in the 75,000 acre Salango Island property in the province of Manabi with the purpose of cultivating hemp to manufacture the canvas sacks used for the bagging of coffee and rice. The Salango acquisition was met with stiff resistance from the peasant farmers located on the land and was eventually liquidated by the corporation (Personal Communication, Carlos Romo Leroux, June 16, 1995).

The hacienda Panigón, which bordered on San Miguel, was purchased in 1934 from Carmelina Ycaza Manzo and her husband Tito Amador Baquerizo. Doña Carmelina and her husband had mortgaged Panigón to the Banco de Descuento for S/.180,000 in 1925. They took out a second mortgage in 1934 for S/.300,000. When they were unable to meet the payments to the Banco de Descuento they sold Panigón to the Agricultura Ecuatoriana, a subsidiary company of the Ecuadorian Corporation.

In 1938 the corporation purchased Supaypungo from Dolores Dorn y Alsúa, who had inherited the hacienda in the partition of the old Naranjito hacienda which had belonged to Vicente Rocafuerte. The Corporation exploited these properties until they were eventually expropriated by IERAC (Instituto Ecuatoriano de Reforma Agraria y Colonización). When these properties were expropriated between 1966 and 1979 they totaled over 6,000 hectares (Uggen 1993).

In 1934 the Ecuadorian Corporation purchased the San Eduardo cement factory for S/.210,000 from José Rodríguez Bonín. The plant began operations in 1924 but closed in 1929 due to the economic crisis. According Carlos Romo Leroux, Forrest Yoder negotiated a ten year lease- purchase agreement in 1934 and changed the name of the plant to La Cemento Nacional (Personal communication Carlos Romo Leroux, June 14, 1995). The Corporation invested heavily in expanding cement production and from 1935-1956 was the sole producer of cement in Ecuador until Cementos Chimborazo began operations in 1956.

In 1938 the Ecuadorian Corporation made its first international acquisition when it purchased a controlling interest in 2 million acres of quebracho forest and grazing lands in Paraguay from the International Products Corporation. The quebracho forests were at the time the principal source of tanin used in the tanning of leather, which gave them a monopoly of tannin extract produced in South America (Ecuadorian Corporation Annual Report 1938).

LIQUIDATION OF SUBSIDIARY OF THE ECUADORIAN CORPORATION

In 1946 the Ecuadorian Corporation liquidated the Quito Tramways company as it was no longer able to compete with bus and automobile transportation in Quito. This was followed the same year with the sale of its Quito Electric Light and Power Company to the Quito municipal power company for S/.8,000,000 (El Comercio, October 19, 1946). In 1956 the Corporation sold its 34½ % interest in the International Products Corporation for $1,100,000 to Pamela J. Woolworth of the Woolworth Department store fortune (Miami Herald, February 8, 1956).

PART THREE: NORTON STEVENS TAKES CONTROL, 1962-1965

Evermont Hope Norton died on Tuesday evening April 4, 1961 at Hopemont, his luxurious residence on the Virginia peninsula. Upon his death Norton’s favorite grandson Hope Norton Stevens, was named to replace him as the head of the Corporation. The following is a list of the subsidiary companies owned by the Corporation upon the death of E Hope Norton:

Table 5: Ecuadorian Corporation Subsidiary Companies, 1961

Source: Ecuadorian Corporation Annual Report, 1961. Elaborated by the Author.

According to Carlos Romo Leroux (Personal communication, June 15, 1995), the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 led the officers of the corporation, now renamed ECL Industries, to assess the long-term future of the company in Ecuador. The board of directors made the fateful decision to invest in new businesses in the United States, which was seen as a safe haven should there be a Cuban style revolution in Ecuador.

Over the next six years management identified electronics and musical instrument manufacturing as promising fields of investment. In 1963 the corporation purchased a controlling interest in four electronics firms. In 1969 ECL Industries purchased a majority of shares in the Chicago Musical Instrument Company, at the time the largest manufacturer of musical instruments in the United States and the owner of several well-known instrument brands, including Gibson Guitars. One of Norton Stevens classmates in the Harvard MBA program was Arnold Berlin, the son and successor to Maurice Berlin, the founder of the Chicago company. Shortly thereafter, ESL Industries changed its name to Norlin, a combination of Norton/Berlin, the name by which it would be known at its final liquidation barely a decade and a half later (Uggen, 2010).

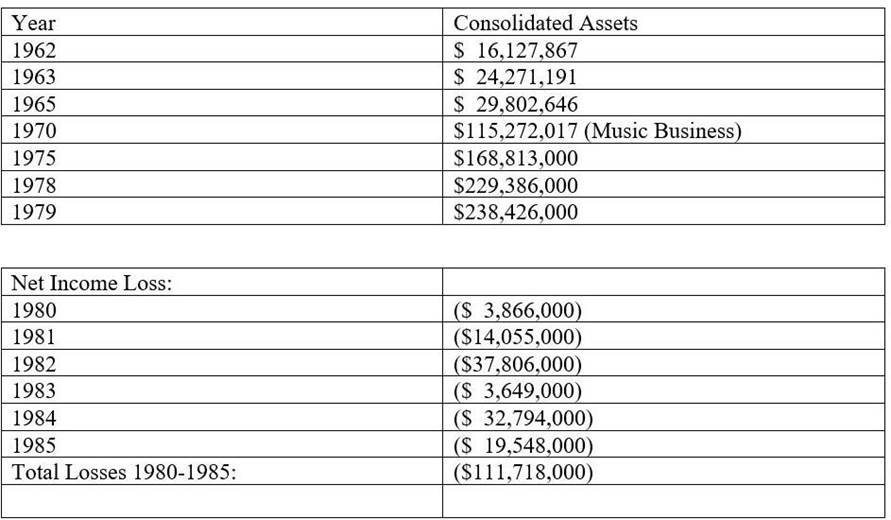

The acquisition of the Chicago company increased the assets of Norlin by a staggering 250%, from $52,848,778 in 1968, the year prior to the merger, to $130,663,013 a year later. The decade of the 1970s saw a steady increase in the company’s assets, which reached their all-time high in 1979 of over a quarter a billion dollars. But at the same time all was not well with the company’s music subsidiary, which began to show losses as early as 1975 due to the recession in the United States and the subsequent drop in consumer spending (Norlin Annual Report 1977).

The music unit, which made up 60% of the company’s earnings in the first half of the decade, fell to a mere 15% at the end of the decade (Norlin Annual Report 1976). The decline in the music business was also an early sign of the mistake the directors had made by abandoning Ecuador for what they hoped would be greener pastures in the United States.

The original mistake in abandoning Ecuador was compounded in 1974 when the corporation sold 51% of its ownership stake in La Cemento Nacional to the Corporación Financiera Nacional. According to Carlos Romo Leroux (Personal communication, June 15, 1995) Norlin decided to get out of the cement business it lacked the capital to meet the expanding needs of the petroleum industry. In January of 1976 the remaining 49% of the Cemento Nacional was sold to the Swiss conglomerate Holder bank, the world’s largest producer of cement.

In October, 1981 Norlin sold off its electronics unit in an attempt to ward off a hostile takeover by Camelia Investments, a British tea company (Wall Street Journal, October 19, 1981). The following year Norlin sold the Cervecería Nacional to Bavaria, bringing to a close the Ecuadorian Corporation’s seventy years of profitable operations in Ecuador. The sale of the electronics and beverage units raised Norlin’s cash balance to $64,341,000 at the end of 1982, further enhancing the company’s attractiveness as a target for a hostile takeover (Uggen, 2010).

Norlin became the target of a hostile takeover for the second time in January of 1984 by the Rooney Pace Group, which had purchased 47.6% of Norlin’s outstanding shares. On September 6, Randolph K. Pace was named chairman of the board and Norton Stevens demoted to vice president of the company that he and his grandfather E H Norton had controlled for 70 years. Stevens resigned on March 5, 1985, severing the final link between the company and Ecuador.

Under the management of the Rooney Pace group Norlin barely survived a year and was closed on March 10, 1986. To make matters worse, Randolph Pace was charged with securities fraud and would eventually serve time in jail. On May 26, 1988 Patrick J. Rooney was convicted of income tax evasion and served time in jail as well. The remaining assets of Norlin, renamed Ameriscribe Corporation, were bought for $83 million by the international conglomerate Pitney Bowes on April 23, 1993.

Although Norlin itself disappeared in 1985, the businesses that were originally developed by the Ecuadorian Corporation have continued to thrive. In a survey conducted in 2002 by the Ecuadorian business journal Gestión, the National Cement Company, now owned by the Swiss firm Holder bank and operating in Ecuador under the name of Holcim, and the National Beer Company, now wholly owned by the South African firm of Saab/Miller, were both listed in the top ten companies in Ecuador as measured by both capital investment and profits (Gestión, 2002). When E Hope Norton died in 1961 the Ecuadorian Corporation’s consolidated balance sheet was

$14,861,066. By 1979, under his grandson Norton Stevens, the corporation’s consolidated balance sheet had grown to $238,426,000, a spectacular 16 times the balance of 1961. The following table 6, illustrates the spectacular growth and decline of Norlin under the management of Hope Norton Stevens:

Table 6: Norlin Consolidated Balance Sheet: 1962-1985

Source: Annual Reports Ecuadorian Corporation. Elaborated by the Author.

One of the main causes of Norlin’s failure was the 1973-1976 recession which was beyond the control of both Norlin and Rooney Pace. A further contributing factor was the plain incompetence and dishonesty of the Rooney Pace Group (Forbes, 1986). Another factor that contributed to the ultimate failure of the corporation was the changing membership of the board of directors.

Under E. H. Norton the board was composed of directors who had been with the corporation from its inception. By the time Norton Stevens came on the board in 1962 E. H. Norton had already passed away and only Forrest Yoder of the founding members was still on the board. The only other senior member was George Herbert Walker, Jr., the maternal uncle of President George Herbert Walker Bush. Norton Stevens replaced the old Ecuador hands by Ivy League graduates with degrees from Yale and Harvard with no previous experience in Ecuador.

Although impossible to prove empirically, perhaps the slow but steady growth of the Ecuadorian Corporation under his grandfather were not spectacular enough for a young Norton Stevens fresh out of graduate school and armed with an MBA degree from Harvard. But the root cause of the demise of the Norlin Corporation must be sought in the fateful decision of Norton Stevens and his board of directors to sell off their cement and beer business in Ecuador to acquire new lines of business in electronics and music in which they had no prior expertise. It is ironic that one of the reasons for leaving Ecuador was fear of being expropiated, while in fact the real danger lay in New York city and the sharks hunting for easy prey on Wall Street.

CONCLUSIONS

The Guayaquil and Quito Railway Company and the Ecuadorian Corporation were the first modern business enterprises to be founded in Ecuador. Their main contributions to the economic development of Ecuador included: the construction of the Guayaquil and Quito Railroad, the establishment of Quito’s street railway system, the urbanization of Quito’s ciudadela Mariscal Sucre, the provision of electricity to the city of 1908 to 1946, the production of cement from 1935-1956, and the manufacture and distribution of the popular Pilsener beer.

The Corporation’s agribusiness subsidiaries introduced scientific farming techniques on the company’s cattle ranch and rice plantation in Milagro. The Corporation also made a significant contribution to the capitalist modernization of Ecuador in the establishment of the holding company and the management structure it adopted to administer the several business units owned by the Corporation.

The completion of the Guayaquil and Quito Railroad fulfilled Alfaro’s vision of the obra redentora which would unify the country under the banner of the liberal revolution. The Ecuadorian Corporation contributed to Alfaro’s vision by establishing the first modern business corporation which served as a model for the great expansion in the number of business enterprises which occurred with the banana boom and the discovery of petroleum in Ecuador’s oriente