INTRODUCTION

The 1930s was marked by the influence of political and economic events that transformed the institutional structure of the country and that, at the same time, behaved as the foundation of a modernization that was not unique to the Ecuadorian case, but that was introduced as part of the institutional modernization models in Latin America. On the other hand, the international crisis had a significant impact on the country's economic stability, especially the stability of the export sectors. The Great Depression created a context of deep political instability, in the Ecuadorian case, within the 1930s, 12 people were registered as head of the executive power in less than 10 years.

The modernization of Ecuadorian institutions came hand in hand with the visit of the Kemmerer Mission, which advised the government on the creation of the Central Bank of Ecuador, which centralized the monetary issue and, together with this institution, several control organisms were created such as the Comptroller General of the State and the Superintendency of Banks. In addition, the gold standard was implemented as the main monetary policy. A good part of the countries of the Latin American region went through similar processes, that is, the creation of national banks, of control institutions, and the restoration of the gold standard.

According to Eichengreen & Temin (2000), the Great Depression produced two phenomena on the prices of goods and products in those countries that maintained the gold standard. First, a deflationary phenomenon due to the reduction in the money supply (Drinot & Knight 2014). Deflation forced industries to reduce production costs, be these from the reduction of wages or from the reduction in the number of workers (Arnaut 2010). This phenomenon stopped when the countries eliminated the restrictions of the gold standard, in the case of Ecuador it happened in 1932. From then on, a second tendency was visualized, this time inflationary because the countries found no legal restrictions for the emission of new currency.

In this economic and political context, the research proposes to analyze some of the most important variables in relation to the working conditions of workers in Ecuador during the 1930s. On the one hand, the context of purchasing power and the wages received by workers will be analyzed, taking into account three groups, namely: first, a group of workers who lived from barter and community survival systems; second, a group of salaried farmers and small business workers who received a daily wage plus certain compensation in kind; third, the group of workers found in the centralized public sector and in the industrial sector.

On the other hand, the different legal bodies that were approved in relation to the labor situation will be described and analyzed. The analysis will focus on the benefits received by workers, including compensation for eviction, premature separation, maternity, disability, overtime worked, in addition to prohibitions of hours and days of work and prohibition of work for minors. The analysis will also include a special section on the implementation of minimum wages in Ecuador as in some Latin American countries.

The implementation of changes in wages as changes in the labor legal systems came along with some populism governments, after the Great Depression, many politicians saw the opportunity to use it as a platform for their agendas: on the one hand, this agenda involved some adaptation of socialism; on the other hand, it involved some adaptation of Keynesian economic models. In all cases, populism was the main characteristic, so there were the cases of Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico (1934-1940), Getulio Vargas in Brazil (1930-1943), Juan Domingo Perón in Argentina (1943-1955) (Zapata 2002). In Ecuador, the first populist government of Velasco Ibarra (1934-1935).

In following decades, there is a clear change in the highland hacienda: the elimination of the

Huasipungo system and the establishment of salary relationships. Moving to the center and north of Ecuador, there was an increasing coexistence of haciendas and smallholdings combining the business economy with the peasant economy this due to agrarian transformations that have converted the peasant from possessor to owner, the landowner initiative: the patron-peasant was replaced by the employer-worker relation (Salamea 1980).

The transformation of farms and the expansion of production in the sector of large farms in several countries forces us to take into account a path different in which the large farm is the one that expands production. What makes this requirement even stronger is the fact that the expansive presence of large-scale exploitation occurs even in countries that had carried out reforms agrarian and even in cases of profound transformations such as the Mexican and the Bolivian (Murmis 1980).

METHODOLOGY

This revision article made usage of the historical-comparative method and the historical-analytical method. With the first, certain similarities, differences and trends have been found in the implementation of minimum wages in the Latin American region. The most important trend was the differentiated implementation of minimum wages based on geographical areas and types of work. In relation to the historical-analytical method, it was useful in the construction of legal, economic and social contexts that shelter labor relations in Ecuador during the studied decade. In this way, quantitative and qualitative new data has been presented and analyzed.

Although the methodology can be circumscribed as part of Social History or Economic History, the article was written within the guide of the historical objectivity that can be found and narrated in research, taking into account their obvious limitations, and in line with the school of thought of the well-recognized Leopold Von Ranke as he saw History as the presentation of facts, “to history has been given the function of judging the past, of instructing men for the profit of future years. The present attempt does nor aspire to such a lofty undertaking. It merely wants to show how it essentially was” (Iggers 2011:86). Thus, the article will develop first within the economic context; then, within the legal system; and, finally, in relation to the minimum wage.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

During the decade studied the region experienced the worst crisis of the XX Century, the Great Depression. Although a variety of symptoms of the crisis can be seen in the Ecuadorian economic system, on the other hand, the GDP continued to grow moderately between 1929 and 1934, at an average of 1.5% (Morillo 1996:687), without registering decrease in none of the years that the crisis lasted.

This is one of the great differences that we find with the Latin American region, whose GDP will fall -16% in the same period (Mitchell 1993:762-764). Nonetheless, the impact in the Ecuadorian economy was mainly registered in the international commerce, which diminished in 55% by 1932 (Naranjo 2021). Within this context, the article develops three themes: economically active population and purchasing power; legal context on working conditions; and, a brief review on the implementation of the minimum wage in Ecuador and some Latin American countries.

ECONOMICALLY ACTIVE POPULATION AND PURCHASING POWER

The data on the economic active population in Ecuador during the 1930s are somewhat obscure because there are no exact references to processes and organized by the central government in the form of national censuses. Thus, the data presented are approximations based on local projections. The National Economic Planning and Coordination Board calculated that by 1962 32% of the population could be considered economically active.

Given the total absence of official data, we have chosen to take this first estimate and extrapolate it for the 1930s. By 1930, approximately 14% of the population lived in urban centers, that is, more than 20,000 inhabitants (Bethell 1998: 31). Extrapolating these numbers, around 116,480 people worked in the urban economy, and around 715,520 in the rural economy. De la Torre (1993) estimates that in 1936, 55% of the Quito population was marginally employed: 10.4% were day laborers, 23.5% were independent workers, and 21.1% domestic workers. Public sector workers represented 16.6% in 1936 (Naranjo, 2017).

According to Linda Alexander Rodríguez (1992), it is known that half of the population was indigenous, who led a sedentary life, with feeding processes based on grains and tubers, they exchanged their tissues for cow's milk, goats or cows, for meat, poultry or sheep wool (Banco Central del Ecuador 1940).

This part of the population lived in a labor context that arose from the Huasipungo, a space of land that was rented for its production that served as a livelihood for families and communities. The concertaje system worked in a common way in rural sectors, especially in the Ecuadorian highlands, generating the isolation of rural sectors from the local and international market. This part of the economically active population was outside domestic consumption and commercial exchange because they interchanged products and were clients of the same products that they cultivated or traded.

In the northern central Sierra, which includes the provinces of Chimborazo, Tungurahua, Cotopaxi, Pichincha and Imbabura, the hacienda system was the base on textile and agricultural production becoming the main source of income for workers, and the main source of industrial development. Creamer (2018) argues that in the 1920s, a textile boom developed which founded the bases for the type of industry that was going to grow in the region, the main representative cases are the Haciendas in Otavalo and the Valley of Los Chillos (Saint-Geours 1994).

The indigenous were the essential mass of the peasantry, as an active part at the hacienda. After the indigenous were the day laborers, small owners and artisans. Then, the mestizos: merchants, carriers, employees, urban artisans. And finally, there are the whites of the city. In 1930, Indians were no longer considered the same way than in 1875. With a certain level of democratization of society, “

” (Saint-Geours 1994: 168).a State more coherent national, international ideological movements and the birth of indigenism, the Ecuadorian Indian ceases to be a simple illiterate labor force

The other twenty-five percent of the population was made up of wage workers and farmers, who were immersed in internal trade. The remaining percentage of the economically active population was made up of public sector workers, merchants, industry owners, renters, who actively participated in the local market. This percentage of the population was also related to the external sector, that is, they were those who consumed imported goods and those who produced export goods.

The purchasing power of the economically active population also varied according to the labor group. From the first group, there is no more information because the population was involved in the exchange and commercialization system under the barter system. Due to the absence of primary data and the complexity of making calculations based on commercial exchange and not on the monetary value of a job, it is impossible to calculate exact amounts.

In this sector, there is only a qualitative assessment of the social and labor conditions in which they lived during the decades studied. This group is characterized by the production and consumption of agricultural products such as sugar, cotton, corn, rice, bananas, pineapples, oranges, lemons, etc (Stevens 1940).

In the second group, the percentage of the population that was made up of salaried workers and farmers, we have little information, which comes from primary sources from the center of the country. According to salary data paid in 1936 to baker's assistants, they received between 2-5 sucres daily (Figure 1), which could represent a sum of between 40 and 100 sucres per month, which could include between 4 and 10 sucres more if weekends are taken into account. The work in the large cattle ranches was better paid, with a salary of around 75 sucres per month in 1936. In addition, as the account book shows (Figure 2), the workers also received extra payments in goods, be they in cattle, beef, sheep, potatoes, corn, etc.

In this second group, primary information from pensions can be added. Presidential decrees from 1928 mentioned pensions from 66 to 143 sucres monthly for a primary teacher, equivalent to the average received in the last five years. Furthermore, wages paid in Hacienda Tungurahua in 1928, in the amount of 60 sucres for doormen and stamp sellers (Official Gazette N.604 1928), can give a clearer panorama of the income situation of salaried workers and farmers.

Primary Source: Hacienda Guachalá y Anexas 1936

Figure 2: Plantation Guachalá y Anexos, Accounting books

In the third group, constructed from the economically active population found in the public sector, workers in industries and merchants, the data from Naranjo (2017) showed that the lowest-paid employees and workers had, on average, an income of 91 sucres per month within 1920s. However, these wages had fallen sharply during the international crisis: the Great Depression reduced unskilled wages by about 25 sucres from 1929 to 1935. As expected, this group, which is directly involved with the local market and with national transactions and trade, they received a higher remuneration than the other groups.

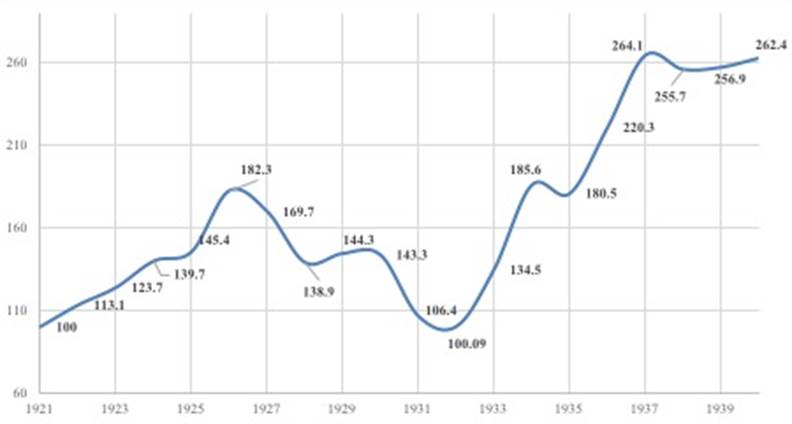

Based on the data, it can be seen that wages fluctuated in direct relation to the price index. That is, until 1932, taking into account the deflationary phenomenon, real wages increased because nominally they remained stable since 1929. After 1932, when policies related to the gold standard are set aside, inflation has a direct impact on wages: real wages decreased while employment increased due to the growth of the money supply, confirming the Phillips curve (Naranjo 2021). As can be seen in Figure 3, the growth of inflation stops in 1937, with which it can also be said that wages begin to stabilize from the same year.

The purchasing power of the economically active population of Ecuador can also be seen from the differentiation of groups. In the first group, the one that lived from the fruits of its agricultural and livestock production, and from the community exchange system, its purchasing power remained stable despite the international crisis because its commercial movement was internal and did not depend on fluctuations in prices that occurred in the domestic market. This sector of the population behaved as a cushion of resistance during the international crisis because their way of subsistence did not depend on national or international trade.

In this way, it can be understood that, from 1929 to 1932, Ecuador grew an annual average of 0.6%. However, during the recovery period, this part of the population became a heavy burden because it did not generate more production: after the impact of the international crisis, the recovery process was very slow compared to the rest of the Latin American region. From 1932 to 1939, Ecuador grew an annual average of 3.5% while Latin America grew an average of 5% (Naranjo 2017).

On the other hand, the second group, made up of salaried workers and farmers, as well as the third group, made up of public workers, merchants, exporters and agricultural owners, did see their purchasing power affected during the Great Depression in both trends previously described: a rise in purchasing power until 1932, and then a steady decline until 1939. Wages in 1937 are only comparable to 1928 wages, meaning purchasing power did not grow for a decade. According to Feiker (1931), Ecuador, with a population of around two million people, had a low purchasing power, similar to that of a Nordic country of two hundred thousand people.

LEGAL CONTEXT ON LABOR CONDITIONS

The Ecuadorian labor context is studied from three perspectives: first, the current legal system for the decade; second, the implementation of social security; third, the analysis of the minimum wage. The labor system allows the construction of a clear vision of the environment in which these activities were carried out; on the other hand, the study of social security show the first legal benefits that workers obtained; finally, the analysis of the minimum wage allow to visualize how this element was the product of an international wave towards the approval of legal minimums for subsistence.

In relation to the legal system in the labor issue, in the thirties several provisions can be found to the conditions of the worker, the first was configured in the Penal Code of 1906. This code was in force throughout the decade of the thirties, with prison for those who decreased the wages (art. 298). A few years later, on September 11, 1916, the hours and days of work were legally established, “by which the hours and days of work are set, in eight the first and six the second, per week” (Albornoz 1931:52). In 1921, the Law on pecuniary compensation for the worker or day laborer due to work accidents was published, on July 13, 1925; the Social Welfare and Labor Section was created on July 13, 1926.

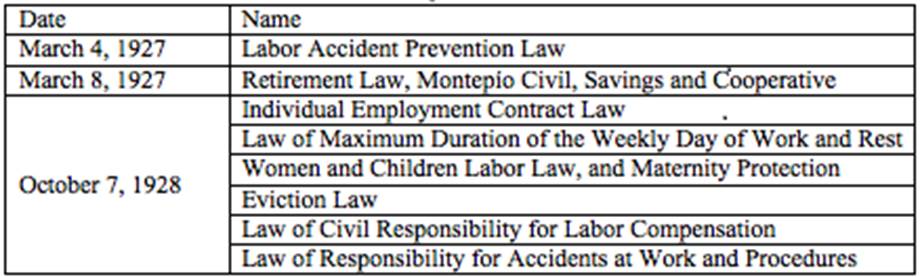

At the end of the twenties, several legal bodies were created on the labor:

Individual Employment Contract Law: this legal body did not have a clear concept of the meaning of employee and employer; the legal events for the eviction were established; and, if the forms of compensation for an untimely or premature dismissal are published.

Law of Maximum Duration of the Weekly Day of Work and Rest: in this legal body, work eight hours a day and six days a week was established as mandatory for private or public employees; public workers have rest days that are established by decree in the norm, Christmas, or Civic Day; payment for overtime worked was established; and the working day is divided into two, with a break in between.

Law on the Work of Women and Children, and Protection of Maternity: it strictly prohibited the work of minors under 14 years of age; employers are obliged to formalize the primary education of those workers under 18 years of age; for workers under 18 years of age, the maximum time for their working day was eight hours per week; In relation to women, work on night shifts was prohibited, in addition, an employer subsidy was required for six weeks, three weeks before and three weeks after childbirth.

Eviction Law: it legalized the penalties for untimely or premature dismissals, in addition to establishing the requirements for evictions and compensation.

Law of Civil Responsibility for Labor Compensation: in addition to the eviction law, which, once the requirements for compensation and evictions have been regularized, the law of civil responsibility for labor compensation was enacted. In this legal body, compensation was tied to the seriousness of the case due to a work accident (Albornoz 1931).

Law of Responsibility for Work Accidents and Procedures: the legal body was published in 1928, it is made up of two parts: first, the responsibilities of the worker in accidents and work-related illnesses; second, the responsibilities of employers in relation to the partial disability of their employees due to labor problems, “

” (Guerrero 1937:22)the victim has the right to be compensated with an amount equivalent to two years' salary

Although this legal context can give a clear idea of how the centralized public sector worked, it cannot say the same about the private sector, the informal sector, and even the public sector in provinces other than Pichincha and Guayas, the most important provinces politically and economically.

We have not found reports that clearly show the application of this body of labor laws in the sectors described, this is logical or, at least, predictable, due to the high rate of informality in the private sector and because the functionality of the public sector, apart from Guayaquil and Quito, it was extremely weak. Despite this, it is highly likely that this legal body on labor has been applied in the centralized public sector and even in a certain part of the industrial sector; however, it is very probably that it was not applied in most of the informal sector.

In the case of the peasants and part of the indigenous sector who lived inside a huasipungo system, the context of the labor system did not correspond to the reality that was lived. In many cases, this group of workers were “landless, homeless, without belongings of any kind, they commit, sometimes for life, for a minimum amount whose debt is never extinguished” (Albornoz 1931:47).

The adaptation to this labor system came gradually in later decades as the nation's economy improved and the companies grew over time and multiplied in number. Social security was founded in Ecuador as a state order regime in 1928, from the “Pension Fund, which mainly established the benefits of the retirement, civil and mortuary fund in favor of civil and military officials” (Instituto Nacional de Previsión 1939:5).

This Pension Fund included several benefits for workers such as reimbursement for contributions, income for disability and work accidents, work-related illnesses, medical assistance, retirement systems starting at age 75 or with a total of 20 years of contributions, “if the worker is unemployed or withdraws from the Fund for any other legal reason, their contributions are returned intact” (Instituto Nacional de Previsión 1939:7).

On July 31, 1936, the strike law was published, which contemplated the right to stoppage by workers after all means of institutional conflict resolution had been exhausted,

… they must comply with the requests of the employer, to which 51% of the factory workers have to adhere... and they can only declare a strike if, three days after receiving the aforementioned declaration, the employer remains silent or responds negatively. (Pan American Union 1937:25)

A BRIEF REVIEW OF THE MINIMUM WAGE

Within the analysis of labor conditions, it is essential to refer to the establishment of the minimum wage in Ecuador and in the Latin American region because it arised as part of a regional change towards the protection of certain labor rights and the establishment of minimum wages necessary for subsistence. In the case of Ecuador, the minimum wage was established as a legal norm in 1936,

…

. (Guerrero 1937:22-23)another important achievement is the relative minimum wage. The lack of legal fixation of the same, was a vacuum that had to be filled urgently... after long investigations it was possible to indicate the minimum wage in one sucre per day in the mountains, and two, on the coast

This regulation, like the previous ones described, did not guarantee a minimum payment for the entire working population. As was logical, the minimum wage was in force in the centralized public sector and in a certain part of the industrial sectors; however, its application was dispersed among the other two sectors of the economically active society, that is, the salaried agricultural sectors and the indigenous and peasant sectors that lived within their local market. The case of the peasants,

…

. (Moreno 1992:73)many of them do not receive any salary in cash, rewarding their services with the land they occupy; others, according to the relationships and agreements of the rustic farms, in the mountains, receive salaries that fluctuate from twenty to fifty cents, and in warm regions, from eighty cents to two and three sucres

As part of the labor situation of workers in the thirties, it is relevant to analyze the establishment of the minimum wage as the state and legal recognition of minimum lower barriers necessary for the support of a person. In the specific case of Ecuador, the minimum wage was legalized taking into account the difference between regions and labor groups, thus, for example, 25 sucres was imposed for jobs in the interior, 50 sucres for jobs on the coast, 37.5 sucres for jobs in the capital. Next, the implementation of regulations regarding the minimum wage in Latin America will be reviewed.

MINIMUM WAGE IN LATIN AMERICA

The countries that are reviewed and analyzed below went through their own local and national political contexts, however, all point to the creation of minimum wage barriers that allow workers to have an income as a minimum necessary sustenance. For this, the situation of workers in the public sector, geographical differences and transportation problems in specific localities, labor demand in private sectors, and the possibility of employers making these payments were taken into account. Thus, it can be understood how several countries legalized different types of minimum wages depending on the geographical position, the exchange rate and the type of work.

The Latin American region was witnessing, in the 1930s, a wave of implementation of minimum wages, either through legal bodies or through constitutional changes. In the constitutions of Brazil, Mexico, Uruguay and Peru were clear the need to establish constant minimum wages (Owen 1938). The rest of the countries in the region welcomed them over time and within their own political context.

The legal changes around the implementation of minimum wages came along with some populism governments which encountered the economic crisis of 1929 as the opportunity to claim the guilt on the northern hegemon. As many governments of that period sought the electoral support of the popular masses, the political leaders offered to establish benefits for the workers and employees such as Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico (1934-1940), Getulio Vargas in Brazil (1930-1943), Juan Domingo Perón in Argentina (1943-1955) (Zapata 2002). In the case of Ecuador, the changes where produced within the context of the Julian Revolution (1925-1932), and the entrance of the first populist government of Velasco Ibarra (1934-1935).

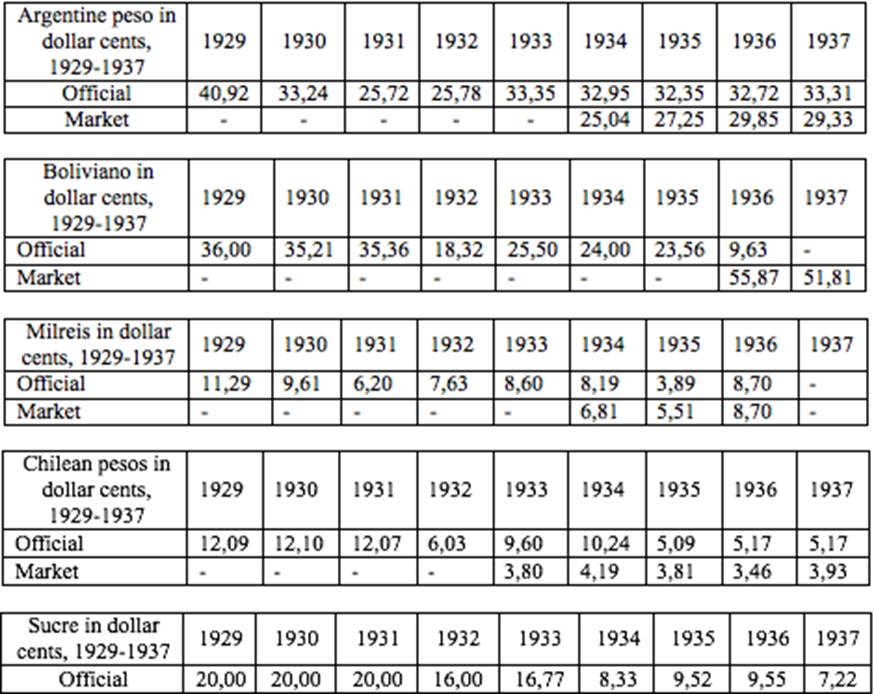

In the cases of Ecuador, Cuba, Costa Rica, Chile, Brazil and Argentina, multiple commissions were created to study the different possible minimums that could be established. With this purpose, Table 2 has been used to present the minimum wages in USD. According to Owen's report (1938), the legal processes that occurred in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile and Ecuador will be analyzed in the following section.

ARGENTINA

In the case of Argentina, in 1929, Law 11.544 was passed, which regulated the length of the working day, it was established 8 hours per day or 48 hours per week. In 1933, Law 11.723 was passed, compensation and paid vacations were some of the most important amendments for workers in the sector commercial. In 1934 Law 11.933 was passed through of which the compulsory maternity leave was established from the 30 days prior to the birth, and up to 45 days after (Cámara Argentina de Comercio y Servicios 2018).

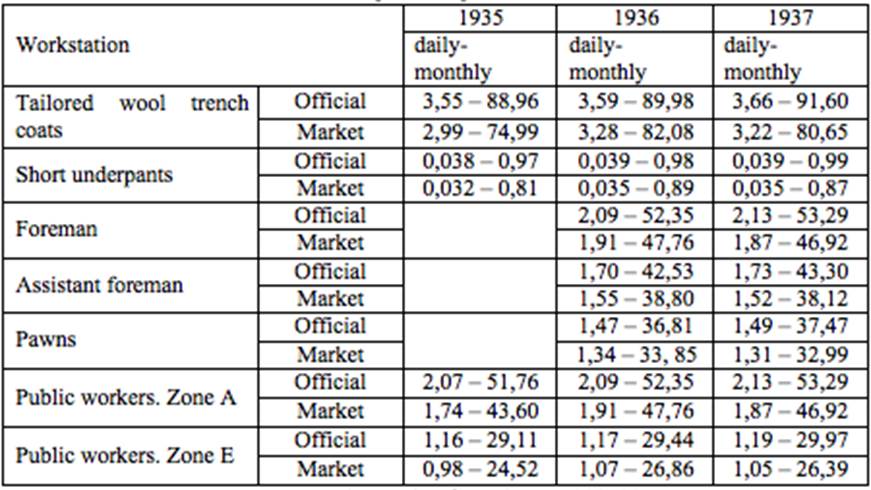

The first sector in which the minimum wage was imposed and legalized was in the public sector. Public sector workers, through a legal decree on September 28, 1934, were divided into two geographical zones, each of these zones were accompanied by a letter, zone A and zone E: zone A: 160 pesos monthly or 6,40 pesos daily; zone E: 90 pesos monthly or 3,60 pesos daily. Minimum wages for the private sector were implemented on April 15, 1935 for the textile industry and on June 9, 1937 for footwear companies.

Within the textile industry, wages are also differentiated between those who work in wool raincoats and those who work in shorts. The former with a minimum of 11 pesos, and the latter with a minimum of 12 pesos. The masons' strike of 1936 (Owen 1938) caused the authorities to publish the resolution of March 24, which formalized the minimum wage for foremen (6.40 pesos), foreman assistants (5.2 pesos), and pawns (4.5 pesos).

The minimum wages in Argentina have been converted to their corresponding value in US dollars in order to have a common measurement for comparison with Latin American countries. As can be seen in tables 2 and 3, the minimum wages in US dollars vary depending on the industrial sector, with the best paid being those workers who were in the trench coat textile industry, while the workers with the lowest wages were those who the public sector of zone E.

Although the jobs that paid the least were those of short underpants, the workers were not only dedicated to the manufacture of underpants but also to other elements of the textile sector. For this reason, they were not identified as the sector with the lowest income. Finally, although working days were officially considered based on 25 days, the days worked per month varied according to the productive sector. In 1945, and through the Decree 1740, the Secretary of Labor and Forecast Juan Domingo Perón generalized the right to enjoy paid vacations workers from all sectors.

BOLIVIA

In the case of Bolivia, on June 27, 1933, the decree was published by means of which the increase in wages was legalized in both the public and private sectors. These salaries increased percentage-wise, depending on the productive sectors and monthly income: those workers with a salary higher than 1,201 bolivianos per month, the salary increased by 780 bolivianos; those workers with less than 100 bolivianos per month, the salary increased by 120%; those workers with a daily salary of one boliviano, the increase was 120%; and, those domestic workers who received up to five bolivianos per day, the increase was 80% (Owen 1938).

Four years later, in 1937, the minimum wage for the commercial and industrial sectors was legalized. The workers received a minimum wage of 140 bolivianos, without gender identification; for those workers considered older adults, their minimum wage were five bolivianos a day; while, for minor workers, between 14-18 years old, their salary were three bolivianos per day. This regulation excluded workers in the agricultural sector with a total of assets that did not exceed 50,000 bolivianos.

As can be seen in tables 4 and 5, the minimum wage adapted to US dollars is divided into three sectors: the first, the industrial commercial sector, with a minimum wage of 72.53; second, workers considered as older adults, with a monthly minimum wage of 64.76; and, the third group, minor workers between 14-18 years old, with a minimum wage of 38.85.

BRAZIL

The minimum wage was established in a process of negotiations between 1934 and 1937, during the presidency of Getúlio Vargas (1930-1945). The Federative Republic of Brazil (1934), in the Constitution, sanctioned the minimum wage as remuneration “

” (art. 121).capable of satisfying, according to the conditions of each region, the normal needs of the worker

On January 13, 1936, a decree was published by means of which there was a special treatment for the salary of federal civil personnel, which was included in the law published on January 13, 1936. Those workers with a salary of less than 150 milreis, increased to 200 milreis; workers with an income between 150 and 1,500 milreis, their salaries increased by 40% up to 500 milreis, 20% per penny up to 1,000 milreis, and 10% per penny up to 1,500 milreis. For that group of workers with an income between 1,500 and 2,500 milreis, the increase was 300 milreis. Workers with an income between 2,500 and 3,000 received an increase of 250 milreis. And, workers with income between 3,000 and 4,000 received an increase of 200 milreis.

From the Constitution, approved on November 10th, 1937, Brazil accepted the prevailing need for a “minimum wage capable of satisfying, according to each region, the normal needs of work” (Owen 1938:326). For this purpose, various commissions were organized to raise minimum wages based on geographic division. These differentiated salaries were later approved through an executive decree.

In all cases, it was accepted that underage workers received a salary corresponding to half the income of an adult; those jobs that were carried out in insane conditions were entitled to a salary and a half. In addition, all work performed with an income below the minimum wage was canceled and the employer was required to pay the difference for the time worked.

As can be seen in tables 6 and 7, in 1936 the minimum wage was established according to previous earnings. The lowest minimum wage was $17.50, and the highest minimum wage was $278.40.

CHILE

In the case of Chile, the labor code was approved on May 13, 1931, through which minimum wages were regulated based on negotiations carried out between commissions. A commission made up of three representatives of the group of workers; and, another commission made up of three representatives of the business and industrial sectors. These commissions would regulate the condition of the minimum wage and stipulate the resolution of conflicts with the General Labor Inspector (Vergara 2014).

One of the industries that received differential treatment was the nitrate industry. The wages for this productive sector were published on January 8, 1934: those workers who remained in single marital status received a minimum wage of 10 pesos per day; for those workers who were married or were heads of family, they received 15 pesos per day; and, those workers who were older adults, had a disability or were minors, their salary was calculated at the rate of 50% of the salary of a single worker.

The Superior Labor Council began to discuss a proposal for a bill on the minimum wage, which was approved in March 1935 to be presented to the national congress. The bill contemplated a minimum daily income that should not be less than two-thirds nor more than three-fourths of the normal or currently paid salary in each area of the country.

The government of President Arturo Alessandri (1932-1938), “by decree no. 1009 of October 11, 1935, appointed a commission to study the conditions of application of the minimum wage and propose legal measures that would substantially improve the income of workers through the family wage” (Yáñez 2019:12). This commission proposed a living and family wage for different areas of the country, which should meet the basic needs of an entire year, especially an intake of 3,000 calories per day for each worker. The result was a salary of 10.50 pesos in Zone I, and 8.03 in Zone V.

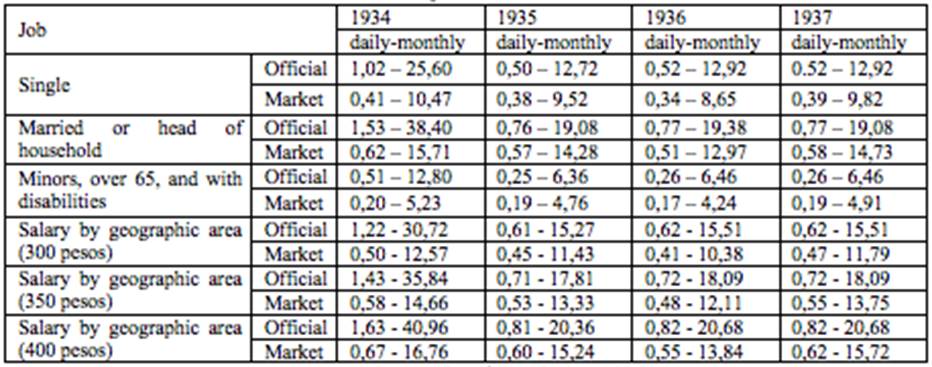

A few years later, in 1937, the salary was legalized for the entire private sector. This time the salary was divided according to geographical areas: 300, 350, and 400 pesos per month. In the case of the municipality of Santiago, the minimums were established at 12 pesos per day for temporary workers and 13 pesos for the group of permanent workers. As can be seen in tables 8 and 9, the salary in US dollars fluctuated between 4.24 and 15.72, while the lower limit was 8 for the group of workers made up of minors, older adults and workers with disabilities.

ECUADOR

In the case of Ecuador, conversations on the establishment of a legal minimum wage happened during the Constitution of 1929. Nonetheless, the wording did not entail an exact quantity, article 151 only mentioned that the minimum wage must be based on costs of living and the regional climate conditions,

. (art. 151.18)The law will set the maximum working day and the way to determine the minimum wages, in relation, especially, to the cost of subsistence and to the conditions and needs of the various regions of the country. It will also set the mandatory weekly rest and establish social security

The minimum salary was legalized in 1936, after a series of labor problems and political agreements. It should be taken into account that as of 1932 the stability of Ecuadorian politics was very weak, with around 12 people as representatives of the executive power until 1940. In 1934 occurred one of the most important labor conflicts of the decade, the paralysis of the La Internacional factory, one of the most important textile industries in the country. According to the Ministry of Government and Social Security, in its Report to the Nation, it mentions that one of the main requests of the leaders of the strike was “that the minimum wage of 1.50 sucres be established in eight hours of work” (Baquerizo 1934:74).

In the report, the Minister of Government and Social Security, Mr. Rodolfo Baquerizo Moreno, recommended that in order to put into practice the desire to set salaries, “

” (Baquerizo 1934:74).it was convenient for the Honorable Congress to issue a Special Law on the individual, prior to the in-depth study of the various zones and customs of the country

In the Senate, on November 26, 1934, the definitive draft of the Minimum Wage Law was achieved. These results indicate that the process of elaborating the legislation on the minimum wage was truncated. No progress was made in the 1934-1935 juncture towards the final phase of enactment of the law, “

” (Creamer 2018: 36).the fact that wage fixes responded to agreements between the parties until 1936 reflected a legal vacuum linked to the weak capacity to elaborate wage legislation for the industrial sector during the politically unstable period from 1931 to 1935

Thus, after several months of political instability, labor pressures, and legislative agreements, in 1936 the Organic Labor Law was published, establishing the minimum wages in the country (Registro Oficial No. 205, 1936). In this it responded to the agreements that are reached between the interested sectors, to say: the sector of the workers, the industrialists, and the central government.

The legal body divided the minimum wage into two parts, one wage for the manual worker, and another wage for the agricultural worker. In 1937, on February 4, in an executive decree ordered by President Federico Páez, minimum wages for agricultural workers and private employees were established.

In the case of the manual worker, the minimum wage was 2 sucres per day on the Coast and 1 sucre per day in the Sierra. The capital, Quito, received differentiated treatment, the worker received a salary of 1.5 sucres. In the case of the agricultural worker, the minimum payment was also differentiated.

Workers on the Coast earned 1.2 sucres, while workers in the Sierra received 0.60 sucres. In the case of workers under 18 years of age, and women, whether in the manual sector or in the agricultural sector, the minimum wage was calculated at a rate of 2/3 of the established one. The legal body did not describe the salary of domestic workers (Pan American Union 1937).

As can be seen in Table 7, the minimum wages were divided into sectors and geographical areas, namely: manual workers and agricultural workers; in the Sierra, on the Coast or in the capital (Quito). Thus, the salary could fluctuate from USD 1.17, in the case of agricultural workers in the Sierra, to USD 4.77, in the case of manual workers on the Coast.

Table 7: Minimum wage in Ecuador in USD, 1936-1937

Source: Autor´s from Pan American Union 1937: 416

Thus, in the case of Ecuador, the labor sectors could receive from 25 sucres per month in the Sierra to 50 sucres on the coast, and 37.5 sucres in Quito. In the agricultural sector, the worker with the lowest salary received 15 sucres a month in the Sierra and 30 sucres in the Coast.

CONCLUSIONS

The decade of 1930 involved a two-period process: first, the one that receives the impact of the Great Depression; second, the one that presents a slow recovery. The first is characterized by the implementation of monetary instruments such as the gold standard and the centralization of monetary emission through the Central Bank of Ecuador.

The second is characterized by the growth of monetary emission, the growth of inflation and the growth in political instability. This instability opened the doors for the entrance of populists’ governments, such is the case of Velasco Ibarra, not being the only one in the region, but incorporated with the governments of Gertulio Vargas in Brazil, Perón in Argentina and Cárdenas in México.

Within this context, the article reviews three important aspects: the economic active population, the legal system on labor; and the minimum wages. In relations to the economic active population, it can be divided into three groups: those who live in a barter system; those who work in Haciendas, are wage workers or farmers; and, those who are part of the worker in industries, merchants or part of the public sector.

The first group has little information on labor, nonetheless, the article shows that it is characterized by the production and consumption of agricultural products such as sugar, cotton, corn, rice, bananas, pineapples, oranges, lemons, etc. In the second group, the salary data paid in Haciendas or Bakeries is 2-5 sucres daily. In the third group, the salaries varied from unskilled to skilled workers.

In relation to the legal system, among the benefits that were implemented within the decade are the compensation for eviction, for premature separation, for maternity, for disability, for overtime worked, in addition to prohibitions of hours and days of work and prohibition of work for minors.

As has been argued in the article, the applicability of these legal bodies can be presumed in the labor sectors of the centralized public sector.

In other words, a complete or almost complete application of labor legal systems can be presumed in those workers who belonged to the public sector and those workers in the largest industrial sectors of the country. No reports or reports have been found that analyzed the labor situation from the application of the approved legal systems in the other sectors of the population. This is understandable due to the informal labor context and because a high portion of the economically active population lived in barter systems or in labor contexts whose salaries included payment in kind.

In relation to the minimum wage, in the case of Ecuador, while in the Central Sierra of the country the wage was one sucres per day, the minimum wage for the Sierra was 25 sucres and for the Coast 50 sucres. These data cannot be generalized to all regions of the country; however, they give us a brief and contextual appreciation of the employment situation.

In relation to the Latin American region, two clear trends can be observed. First, a trend of approval of minimum wages in the 1920s and 1930s. Second, there is a tendency to differentiate minimum wages according to geographical areas, the age of the workers, and their family or physical situation, that is, differentiated wages for people with disabilities, and differentiated wages for married women