INTRODUCTION

Biodiversity, its conservation, and its responsible use occupy a central space in current debates on politics, science, and economics. At the Rio de Janeiro Summit, held in 1992, a discussion area was dedicated to the problems of the planet's survival, which resulted in the signing of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Of the many definitions of the term biodiversity, the one adopted at this event is the most comprehensive, considering it as: “(…)

” (Naciones Unidas 1992:3).the variability of living organisms from any source, including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; includes diversity within species, between species, and of ecosystems

Although not much progress has been made in a general sense in complying with the agreements of that convention, the issue remains open and is reviewed periodically, due to the importance it has for the world and in particular for developing countries. It is precisely in these countries where the highest level of biodiversity exists, and also where it is most threatened. Latin America and the Caribbean stand out for their exceptional natural wealth, when compared to other regions of the planet, and also for the danger of erosion of these resources (León and Cárdenas, 2020).

The very conception of biodiversity as a set of resources is misleading: Klier (2016) and Martínez et al. (2018) agree in stating that the preservation of biodiversity is assumed in western policies as the conservation of “the other”, that is, of animals, plants, and areas that, due to their characteristics, differ from the model of what is considered a developed society. In this way, communities and cultural practices associated with biodiversity and its responsible use by the members of these communities are excluded, and nature is given the connotation of merchandise.

Developing countries, on the other hand, need to boost their economy, and most of them cannot do so if it is not at the expense of the rational use of that biological diversity that they must also protect. The concept of bioeconomy has recently emerged to define the efficient use of biological and natural resources, as well as the use of their waste to reduce the use of fossil energy and decarbonize the economy (Hodson, Henry & Trigo 2019).

This article intends to reflect on the connections between Latin American biodiversity and its possibilities of insertion in the bioeconomy, without violating the cultural practices of ancestral peoples.

METHODOLOGY

This is a reflective article in which current information on the state of biodiversity in Latin America was analyzed, its link to the cultural practices of indigenous peoples, some examples of attempts to appropriate these resources by institutions and individuals, and the need to use the resources that biodiversity provides based on a model supported on the bioeconomy.

It is ascribed to the constructivist hermeneutic paradigm and the type of research is grounded theory. A review of documents on the topics addressed was carried out, which was used to formulate reflections on what the authors consider appropriate for the projection of the Latin American bioeconomy, through a balanced interaction between research, educational, productive and governmental institutions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

BIODIVERSITY IN LATIN AMERICA

The exceptional animal and plant wealth present in Latin America and the Caribbean is a proven fact; almost 60% of the terrestrial species that inhabit the planet are found in this region, in addition to being characterized by a diverse marine and freshwater flora and fauna (UNEP 2018).

In the particular conditions of Latin America, where large unexplored areas and communities that have not come into contact with "modernity" persist, the vision of biodiversity is polarized in two directions: on the one hand, the western/usufructuary, in which everything what exists on planet Earth can be considered a resource and is susceptible to massive exploitation; on the other, the traditional/indigenous, attached to respect for nature, coexistence with all species, and its rational use and even worship. Unfortunately, as pointed by Martínez et al. (2018) although the properties of a resource are independent of human being, it is the latter who attributes its market value to it and who determines the extent to which it is exploited or conserved.

From this perspective, a concept of biocoloniality is applied to the management of biodiversity (Beltrán 2016), on the basis that modern science is the only one capable of discerning truths and demonstrating concepts, which results from a dominant cultural reason projected to starting from the colonial domination itself that in other spaces (political, social, religious) modernity has exercised over the indigenous.

As this author points out:

. (Beltrán 2016:216)The point is that Western thought, in its homogenizing and hegemonic tendency, has believed that its version is the version of the meaning of life and existence, without recognizing that other ways of seeing humanity and its existence are also valid, as well as the world it inhabits

This violence is exercised even from the epistemological point of view, since the distinctions made between terms such as scientific knowledge and traditional knowledge reveal a supposed relationship of superiority of the former over the latter (Beltrán 2017).

Research has been used in many cases as an excuse for the appropriation, by scientific institutions and private companies, of the resources that biodiversity offers, for their use in modern scientific programs and on some occasions to hold a monopoly on that biodiversity (Toro 2007). In this way, attempts have been made to kidnap, with greater or lesser success, the natural resources of Latin American biodiversity in order to use them for business interests.

The most biodiverse Latin American regions are also those in which peoples, tribes and communities reside with habits, customs and cultural practices closely associated with that biodiversity.

A primary consequence of the expansion of agriculture, industry, and urbanism into these areas has been the disappearance of animal and plant species that modern science has not even had time to discover; but that is not the object of these reflections, but the way in which the appropriation of the components of biodiversity has neglected the traditions of indigenous peoples, from a perspective of cultural superiority.

Next, three cases will be presented in which it is shown how the science of developed countries has used native species, linked to ancestral practices of indigenous peoples, stripping them of this connotation and reducing them to that of a market object.

AYAHUASCA

In the Amazon basin, shamans use a concoction they call ayahuasca to induce a state of ecstasy in which visual and auditory hallucinations occur. Although there are different ways to prepare the drink, it is considered that the most common is the mixture of two plants (Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis).

The ingestion of ayahuasca has gained popularity in recent decades, acquiring in some areas an ethno-tourism interest, and even creating spiritual movements around its consumption, such as those called Santo Daime, União do Vegetal, Barquinha and others (Domínguez et al. 2016).

The cultural connotation of the ayahuasca ceremony is undeniable, and in its original form it is considered as a cleansing of the body and spirit, as well as a connection with astral forces. Western science has found the explanation for the hallucinations it produces: Psychotria viridis contains dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a substance with powerful hallucinogenic effects; under normal conditions, the organism inhibits the metabolism of this substance in the intestine, but the β-carbolines contained in Banisteriopsis caapi in turn counteract this inhibition, with which DMT reaches the central nervous system (Escobar 2015). The concoction has shown antidepressant properties (Sanches et al. 2016; Bouso & Sánchez 2020).

Although these discoveries of medical value are relatively recent, ayahuasca aroused commercial interest long before. In 1986, the US citizen Loren Miller, then director of the International Plant Medicine Corporation (IPMC), was granted a plant patent application by the United States Patent and Trademark Office. which he called De Vine, which he had brought from the Amazon jungle in 1981, and which was none other than ayahuasca.

The concession provoked numerous complaints from indigenous communities and an international lawsuit led by the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA). After long years of legal battle, the patent was withdrawn in 1999, but not as a direct consequence of the claims of the native peoples, but on the basis that a specimen of the plant had already rested in the Chicago Museum since before the request. Surprisingly, in 2001 Miller presented new documents and obtained the restitution of the patent until its expiration in 2003, although without rights beyond the genome of the plant and its asexual propagules (Beyer 2008).

PEYOTE

Peyote is a cactus native to the arid zones of Mexico and the southern US. Two species are included under that common name, Lophophora williamsii and Lophophora diffusa. The first of them produces mescaline and the second produces pellotine, alkaloids with high psychotropic effects similar to those of lysergic acid.

Possibly these hallucinogenic properties have transcended much more in the Western world than its therapeutic action on various respiratory, rheumatic, and venereal diseases, which determine its medicinal use by Mexican indigenous people (Ibarra et al. 2015). In addition, Lophophora williamsii produces other alkaloids of pharmaceutical interest such as anhalidine, lophophorin and anhalonin (Santos & Camarena 2019).

This is not the only plant that produces mescaline, since several South American species of the genus Trichocereus also synthesize this alkaloid (Cassels & Sáez 2018). However, Lophophora williamsii is the only one associated with cultural practices of shamanism, divine rites, and dream visions among the Mexican peoples of the Tarahumaras, the Coras and especially the Huicholes (Clavijo 2018).

Mescaline has aroused interest for its pharmacological use in the treatment of headache, depression, obsession, anxiety, and addiction to some substances such as alcohol, in particular because the propensity to become dependent on mescaline is practically non-existent, and intoxications with this substance are moderate and not life-threatening (Dinis-Oliveira, Lança & Dias 2019).

The metabolites obtained from Lophophora williamsii, like those of many other cacti, constitute a potential still little exploited in the pharmaceutical industry (Das et al., 2020), and have not aroused business desires similar to those of ayahuasca, possibly due to the results of the legal conflict surrounding the latter.

POISON DART FROG

The frog Epipedobates anthonyi is endemic to Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador; on its skin there is a powerful poison that has earned it its name and that drew the attention of science starting in the 1970s. At that time, the chemist John Daly, of the US National Institute of Health, collected skins of this amphibian in Ecuador, which possibly left the country through diplomatic channels, since there is no evidence that the Ecuadorian Institute of Forestry and Natural Areas (INEFAN, later merged into the Ministry of Environment) has granted a license for the operation (GRAIN 1998). Laboratory studies led to the synthesis of a non-opioid alkaloid (epibatidine) of pharmaceutical interest.

Epibatidine as a medicine did not prosper, because the threshold between its therapeutic efficiency and its contraindications is narrow; however, it served as a model for Abbot Laboratories to synthesize and patent the derivative ABT-594 in 1995, with an analgesic potency 200 times greater than morphine and without the dangerous effects of epibatidine (Angerer 2015).

Through INEFAN, Ecuador filed a lawsuit against the patent in 1998, without results; the reasons given were that no evidence was found that in Ecuadorian folklore the skin of the frog was used for medicinal purposes, but rather as a poison for hunting, and that the synthesis of ABT-594 was not made directly from the skins of frogs, but taking their structure as a model (Jurado 2021). However, under the bioethical principle of utilitarianism or beneficence (maximum possible benefit for a greater number of people), it is valid to ask why the indigenous communities where the amphibian lives did not receive benefits (Proto 2019).

¿BIODIVERSITY VS. BIOECONOMY?

The appropriating vocation of a part of the Western world towards the resources offered by Latin American biodiversity is not new. Centuries of colonialism reduced Latin America to the status of exporter of raw materials for large industries (food, mining, textiles, and more recently, chemicals and pharmaceuticals) of developed countries.

Meanwhile, these consolidated their hegemony in the manufacture of products made from these raw materials, so that today the probability of developing Latin American industries that can compete in the market with those existing in Europe, North America or even Asia is negligible. What Latin American businessman would try to displace Ford, Toyota, Monsanto, or BASF from the market, even in his own country? However, there is no doubt that the region must continue to grow towards economic development. How to do it then?

There is a space that the development of the Latin American economy can occupy, and it is a paradox that the main resources to do so are found precisely in biodiversity, which, on the other hand, is essential to preserve. The central idea for this projection is based on the bioeconomy, which is centered on the efficient use of biological and natural resources and the recycling of their waste; its use has among its advantages the reduction of the use of energy provided by fossil fuels and the reduction of carbon emissions (Hodson, Henry & Trigo 2019).

The application of an economic model built on the rational use of biodiversity would not only contribute to the health of terrestrial life, but also to the preservation of life itself, which, as Philp (2015) points out, cannot be maintained in the long term in the unsustainability conditions of the current model.

A typical example of what is needed to develop the bioeconomy can be found in Brazil. In addition to having 15 % of the planet's species, Brazil has abundant land, a suitable climate, a low population per unit area and a large amount of natural resources; however, it is also an example of how the export of raw materials diverted the country from the creation of infrastructure, policies, and institutions capable of working from a bioeconomic perspective.

Brazil must “run after lost time” (Valli, Russo & Bolzani 2018), which is also a reality for the entire subcontinent. Latin America enters this race with a disadvantage: between 1981 and 2014, in the pharmaceutical market 1,211 new products were introduced, of which 60 % were obtained from natural substances or were designed from structures found in nature (Newman & Cragg 2016).

Fortunately, Latin American biodiversity is immense, which provides opportunities to take advantage of the existence of numerous natural resources (many already discovered, but the vast majority still unknown) for use in the bioeconomy. See only the two cases described below.

The ever-increasing food needs of the population and the animal species bred in captivity for human consumption are leading to the use of alternative sources of nutrients for these purposes. One of the variants coming to be exploited is the use of flour obtained from insects. The larvae of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.), a species native to America and now widespread throughout the world, can be converted into flour with a high protein content, useful in feeding fish (Meitiyani et al. 2020) and birds (Wahid et al. 2021).

They are even beginning to be used as a substitute for part of the wheat flour in the bakery, with nutritional advantages over the latter in terms of protein and fiber content (González, Garzón & Rosell 2019). In Ecuador, the first soldier fly meal production plant in Latin America was inaugurated at the end of 2021, operated by Bioconversión S.A. on the campus of the Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral, in Guayaquil (El Universo 2021).

Acetogenins are natural substances that exhibit high antitumor activity, several orders of magnitude higher than that of some drugs commonly used in cancer chemotherapy. These compounds are found only in species of the Annona genus, such as custard apple (Annona cherimola Mill.), soursop (Annona muricata L.) and sugar apple (Annona squamosa L.). The phytochemical activity of acetogenins has been demonstrated in vitro, in animal tests, and in simulations of the human digestive system (Gutiérrez et al. 2020; León, Pájaro & Granados 2020; Naik, Dessai & Sellappan 2021; Nayak & Hedge 2021).

The Annonaceae family is made up of about 2,500 species that grow naturally or are cultivated in the tropical regions of America, Asia, and Madagascar (González 2013), but many of these species are native to Latin America, mainly Ecuador, Peru, and Brazil. It is therefore noteworthy that most of the studies on the antitumor potential of acetogenins and their application in pharmacology have been carried out in laboratories in Europe, the USA and Asia.

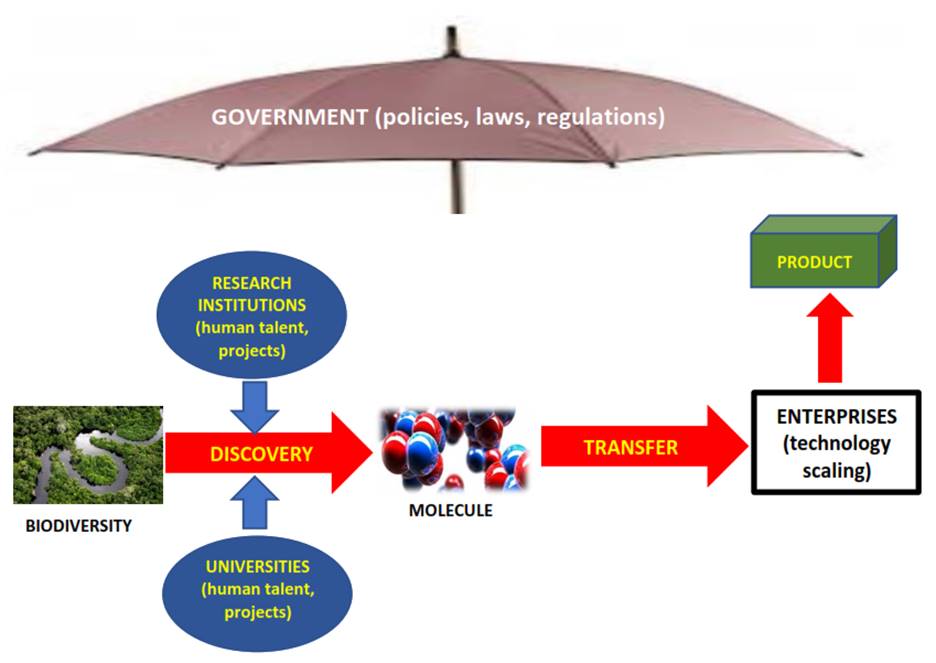

Based on these two examples, it is clear that the region is still very timidly projected towards assuming an economic model that takes advantage of the potential of its biodiversity to generate innovative products within the framework of the bioeconomy. Coordinated efforts of various instances are needed to achieve an education-research-production-policy chain that leads Latin American countries down this path (Figure 1).

Source: Authors' elaboration

Figure 1: Institutional integration in a bioeconomic model for Latin America.

In Latin America, biological wealth and cultural heritage are inseparable, and as Tinoco (2015) points out, both are assets that must be legally protected, so that cases such as that of ayahuasca and the arrowhead frog do not happen again.

CONCLUSIONS

Latin America hosts an important part of the Earth's biodiversity, closely linked to the existence of still unexplored regions and the presence of aboriginal communities that have not been contacted. The indigenous traditions of respect for nature and harmonious coexistence with it determine that this biodiversity is closely associated with cultural practices of different types.

The utilitarian sense of Western culture has caused many forms of life to be converted into bio-resources for science and production, as shown by the cases of ayahuasca, the poison dart frog and peyote. The intentions of appropriation are not limited to the economic aspect, but have transcended the epistemological field, establishing a border between scientific knowledge, obtained by research carried out in laboratories, and the so-called traditional knowledge.

The competitive disadvantage of Latin American countries in the current scenario advises that they take advantage of the potential of their biodiversity to develop their economies. The existence of some examples in this sense shows that it is feasible to do so, provided that the efforts of educational, scientific, and productive institutions are harmonized under government policies of respect for ecology, indigenous communities, and the legal protection of that heritage