INTRODUCTION

A good portion of students, if not all, have been assessed by teachers for a certain work done in class. This assessment could vary among teachers, schools, and even countries. There are plenty of options to assess students’ class performance. For instance, tests and quizzes are two of the many language assessment instruments available for teachers to use. Teachers must be able to choose among this large quantity of language assessment instruments to meet learners’ needs.

However, there is often a misconception about the term assessment, the assessment process itself, and its use. The term assessment relates to students and teachers, given that most of the time teachers are the ones who design the different assessment instruments by taking into consideration their own learners’ needs.

In this study, we will characterize 209 language assessment instruments created by several Chilean English teachers. These assessment instruments come from kindergarten to university teachers and include tools from public and private educational establishments. This study will also describe all the language assessment items and will show the different types of assessment instruments, their educational level, the language system, the language skill presented in the assessment, and the type and number of items.

It will explain the tendency of Chilean teachers of preferring traditional assessment over alternative assessment. This paper is in the context of the research grant FONDECYT 1191021 entitled Estudio correlacional y propuesta de intervención en evaluación del aprendizaje del inglés: las dimensiones cognitiva, afectiva y social del proceso evaluativo del idioma extranjero.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

LANGUAGE ASSESSMENT

According to Le Grange & Reddy (1998:3), “assessment occurs when judgments are made about a learner’s performance, and entails gathering and organizing information about learners, to make decisions and judgments about their learning”. Assessment aims to gather information and evidence of students from original sources to make assumptions of gained knowledge and competences. Boud (1990) stated that assessing students improves the learning quality and the standards of performance.

Several studies show assessment as a positive influence on students (Black & William 1998; Kennedy, Chan, Fok & Yu 2008). It provides feedback, allowing students to acknowledge their strengths and weaknesses to improve their learning process. There is a vast range of assessment methods and tools to help educators assess various aspects of student learning.

Assessment methods are the techniques, strategies, and instruments an educator may use for gathering data on students’ learning. Methods will vary depending on the learning outcomes and the students’ level (Allen, Noel, Rienzi & McMillin 2002), and they can take different forms: tests, rubrics, checklists, rating scales, etc.

TRADITIONAL ASSESSMENT

Traditional assessment, often related to testing and standardized tests, has been challenged by alternative assessment. Many authors agree that traditional assessment is indirect, inauthentic, and it only measures what learners can do at a particular time in a decontextualized context (Dikli 2003). Even though it might be hard to believe that educators still use this type of assessment as their only tool to test, traditional assessment continues to be the preferred norm.

Traditional assessment stands out for its objectivity, reliability, and validity (Law & Eckes 1995), as these aspects belong to standardized tests and multiple-choice items. Traditional assessment often seems to be more practical, since the type of items presented can be easily corrected, and sometimes they are even scored by automatized machines, providing reliable results.

TESTS AND QUIZZES

Tests are powerful tools with a variety of purposes for education (Davis 1993). They help to test and assess whether a student is learning what is expected. A well-designed test can motivate and help students to focus on their academic efforts. As Crooks (1988), McKeachie (1986) & Wergin (1998) claimed, learners study according to what they think teachers will test. For instance, if a student expects a test based on facts, he will memorize information. On the other hand, if a student expects a test will require problem-solving, they will work on understanding and applying information.

Tests and quizzes are different, based on the extent of content covered and their weight in calculating a final grade in a subject (Jacobs & Chase 1992). The focus of a test is on particular aspects of subject-based material, and it has a limited extent of content. There are several test items to measure learning, for instance: multiple choice, true or false questions, reading comprehension questions, fill in the blanks, etc.

It is key to highlight that tests can be adapted to fulfill students’ needs (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2019). A quiz, on the other hand, is a quick test and does not have a great impact on a final grade. A quiz is often very limited in its content extension, and it is a way to keep track of students’ gained knowledge.

LANGUAGE TESTING AND TYPE OF ITEMS

Language testing is often mistaken with assessment, as both terms appear together when we talk about assessment. Language testing is the practice of measuring the proficiency of an individual in using English. It is important to understand this terminology as language tests are part of our education system and society. The scores from tests are a tool to make inferences about individuals’ language ability.

As Bachman (2004:3) stated, “language tests thus have the potential for helping us collect useful information that will benefit a wide variety of individuals.” Testing is as old as language teaching “since any kind of teaching has been followed by some sort of testing” (Farhady 2018:1). From university to school, teachers have used tests to measure students’ abilities and English knowledge.

Most teachers develop their tests as they are a tool for them to decide what to do inside the classroom (Spaan 2006). The prime consideration to develop any test is that of purpose. Thus, test developers need to consider different factors to develop their tests. These factors may vary from classroom to classroom, from school to school, and from region to region within the same country. Spaan (2006:72) defines test takers “in terms of age, academic or professional level, language proficiency level, and possibly geographical location or cultural background”.

The next step when designing a test is to develop the test specifications. Teachers must decide the language skills to be measured (listening, reading, speaking, and writing), and if they are going to be measured as integrated or independent skills. The content and level must also be defined beforehand, along with the design of the test itself. “How long will the test be, both in terms of size and number of items and in terms of time? Will the test be timed or not? Will it be speeded?” (Spaan 2006:74). Scoring is also part of the decisions about the test specifications, and practical considerations, such as the number of students, or the size of the classroom.

What follows next is to determine the type of items to include in the test. Most educators agree that the best tests contain a variety of items and response types to achieve their purpose. No item type by itself has been useful. According to Spaan (2006), the best tests are the ones that contain different item types, “which is fairer to test takers in that it acknowledges a variety of learning styles, balancing objective items with subjectively scored items” (Spaan 2006:79).

Objective items require the individual to select the correct answer from several alternatives or to supply a word to answer a question or complete a statement; while subjective items allow the individual to organize and present an original answer (CTL Illinois 2019). Among objective items are included: multiple-choice, true-false, matching, chronological sequence, and completion; whereas subjective items include essay-answer, open-ended questions, problem-solving, and performance test items.

ALTERNATIVE ASSESSMENT

It is important to support students and make them actively involved in the assessment process (Black & William 1998), to build self-awareness of their learning processes. Alternative assessment includes self and peer-assessment, which aims to develop autonomy, responsibility, and critical thinking in learners (Sambell & McDowell 1998).

The use of alternative assessment over traditional assessment encourages the use of critical thinking and the use of real-world problems, being more meaningful to the learner (Mertler 2016). Whereas traditional assessment only develops the skill of recalling, in which learning outside the classroom becomes meaningless to students.

This idea of a real-life problem is further enforced by Dikli (2003), who explained that several approaches are under the concept of alternative assessment. However, two of them stand out as the most relevant: real-world instructions and the use of critical thinking to solve contextualized problems. The author further describes the activities considered as alternative assessments such as open-ended questions, portfolios, and projects, among others.

RUBRICS

Torres & Perera (2010) define the rubric as an instrument of evaluation based on two scales: qualitative and quantitative. Rubrics are composed of pre-established criteria, which measure the actions taken by a student over a task. Rubrics are specific models to test gained knowledge in the classroom and topics assigned by the teacher.

A rubric is designed as a chart. The chart contains specific descriptors and criteria for the students’ performance. Besides, a rubric always shows the goals to work as a wonderful source of feedback for both students and teachers. Teachers can adapt rubrics to assess and work as a guide for students.

Students can identify the purpose of the topic, the steps to follow, and how they will be assessed (Brindley & Wigglesworth 1997). There are two types of rubrics: holistic and analytic rubrics. The holistic rubric provides a global knowledge appreciation, while the analytic rubric allows focusing on a specific knowledge aspect.

EMPIRICAL STUDIES

Astawa, Handayani, Mantra & Wardana (2017) carried out a study on language test items. The study comprised how different test items presented a high ratio of validity and reliability in an experimental group of teachers in which it had a perpetual effect on language habit development. For this experiment, the authors decided to only work with an experimental group. The experimental group had to create a test focused on the writing skill to analyze if it presented validity and reliability.

After a week of attending the workshop organized by the researchers, the teachers learned how to construct different test items. Likewise, the teachers could identify the principles of validity and reliability in their tests. The last part of the workshop comprised how promptly and consistently the teachers could apply the different test items and the principles to improve the quality of the English language tests in their classes.

Findings showed that the teachers who attended the workshop were better at constructing either subjective or objective English tests. The improvement of the tests was measured by applying the t-test (tests designed by teachers attending the workshop) before and after the workshop. These t-tests were applied to determine the reliability and validity of the test created by the teachers who were part of the experimental group.

Alfallaj & Al-Ahdal (2017) developed a study to investigate and compare the Saudi Arabian EFL testing instruments of Qassim University with the MET (Michigan English Test). The participants were 80 learners from the two EFL courses at Qassim University. They had to submit the scores from their free sample of the MET to draw correlations with the performance of these courses.

Besides, 40 of these participants were given a questionnaire to get feedback on EFL question papers at the University. By doing so, researchers wanted to analyze how reliable the KSA (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) English tests were, compared to international tests, such as the MET.

The findings showed that KSA English learners were not prepared to succeed in the internationally recognized proficiency tests even if they were slightly comfortable with the pattern and content of the University English Tests (UET). In the grammar component, only seven participants scored below 50% in the UET, but in the MET this number went up to sixty-seven. Regarding the vocabulary section, the scores were similar, with sixty-five participants scoring less than fifty percent marks, but in UET seventy-four participants scored between eighty-nine and fifty percent marks.

In the reading test and listening test, the outcomes were much similar: sixty-seven participants scored less than fifty percent marks in the MET, but many participants of this same group scored between sixty and seventy-nine percent marks in the UET. After these results, investigators analyzed the questionnaires in which the participants all agreed that the MET was harder than the UET. Thus, proved that the test components of the UET were not up to the International proficiency expectancy level.

Researchers recommended that English test developers must test their tests to ensure the validity and reliability of them. They recommended the use of a checklist and a series of questions to test if the language assessment principles are present or not before using the instruments in their courses.

METHODOLOGY

The present study is non-experimental and descriptive, and its primary research aim is to characterize the types of instruments, the educational level, the language systems and skills, and the type and number of items identified in a sample of instruments.

The participants in this study are 22 Chilean English teachers from different educational establishments who provided 209 assessment instruments. This intentional sampling is based on the teachers who volunteered to provide examples of their assessment instruments as participants cannot be forced to share their materials. Ten teachers were from subsidized schools, ten teachers from public schools, and two teachers from universities.

The educational grades in which these participants teach range from prekindergarten to 12th grade, including some university courses and primary educational levels in adult school. These participants were contacted online through professional English teachers’ communities or in person over the second semester of 2019.

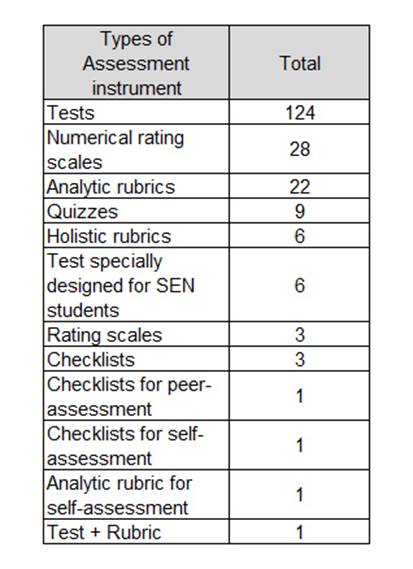

In terms of the types of assessment instruments, a total of 209 was collected. However, four instruments were eliminated, since they were incomplete or not fully legible to use. 205 assessment instruments were analyzed in this research (tests, tests specially designed for students with special educational needs, tests + rubric, quizzes, rating scales, numerical rating scales, analytic rubrics, analytic rubrics for self-assessment, holistic rubrics, checklists, checklists for self-assessment, and peer-assessment). Table 1 shows the detailed number of types of assessment instruments.

Researchers contacted participants online and through in-person meetings to ask for assessment instruments of their authorship. Teachers were informed of the purpose of this study and how it was going to be conducted. They were asked for some personal information, such as gender and the educational establishment where they worked. They were informed that their personal information would be anonymous.

As instruments were received, they were classified according to their educational establishment. Then, to classify the assessment instruments, the data of each assessment instrument was put in a spreadsheet, which contained labels such as: type of instrument, skill measured, system measured, number of items, type of items, scoring system, and level.

Instruments were analyzed following the steps of content analysis, and then a frequency and percent analysis was also used in this study. The data was displayed in tables of frequency that grouped results, such as type of assessment instrument, language systems, and skills measured, educational levels in which assessment instruments were used, number of items, type of items, and scoring system, according to the number of times they were found in the spreadsheet. The creation of graphics came from the data on those tables.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

TYPES OF ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENTS

This study comprised the analysis of 205 types of assessment instruments from different educational establishments (public and subsidized schools and universities). The different types of instruments registered were tests + rubric, tests, tests specially designed for SEN students, holistic rubrics, analytic rubrics for self-assessment, analytic rubrics, quizzes, checklists for peer-assessment, checklists for self-assessment, checklists, numerical rating scales, and rating scales.

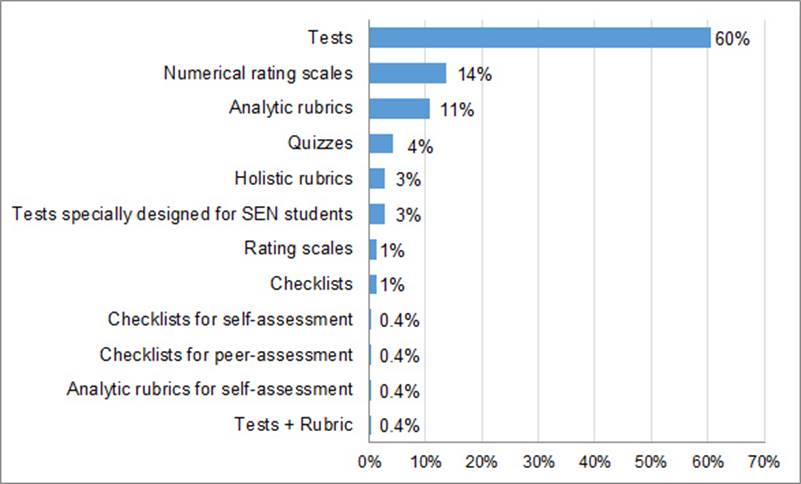

Figure 1 shows that most of the instruments evaluated were tests (60%), followed by numerical rating scales (14%) and completing with analytic rubrics (11%). The least used instruments were tests + rubric, analytic rubrics for self-assessment, checklists for self-assessment, and checklists for peer-assessment (all the previously named instruments share the same percentage 0.4%).

Two hundred and five assessment instruments were analyzed, and twelve different types were registered. The most registered assessment instruments were tests (60%). This result was predictable, as in Chile the most used assessment instruments are tests. Even in important educational instances, tests are mainly used to assess the students’ performance. For instance, SIMCE (Sistema Nacional de Evaluación de Resultados de Aprendizaje) and PSU (Prueba de Selección Universitaria) are two of high stakes examples in which tests and exams are present and may even define the professional future of students.

The fact that tests score the highest in figure 1 may be worrying in foreign language learning because not all the skills (reading, listening, writing and speaking) can be assessed through tests. Productive skills (speaking and writing) require the use of more authentic communicative tasks that encourage students’ language production. Some examples of these are interviews, oral presentations, video creation, poster presentations, which are all tools that are from tests.

Tests are perhaps the most common and practical assessment instruments to assess learners’ responses in a classroom. Coombe (2018) described tests as practical since they help teachers to assess and in most of the cases, grade students’ performance and give valuable feedback to the learner. Moreover, tests are fast and economical to correct, they also provide objective results in the form of scores among students, in comparison to other assessment instruments, which rely on subjectivity given the wide variety of answers learners might provide, causing some reliability issues (Dikli 2003).

Tests are an important part of the Chilean educational assessment policy because of their versatility and easiness when creating them. This fact may be influenced by some contextual factors of Chilean education. For example, the number of students in classroom tends to be high in schools; therefore, the use of tests and quizzes that employ traditional item types are very often a solution for quicker scoring and marking.

In addition, there is still the wrong belief that tests and quizzes are much more objective than an assessment task that requires the use of a scoring scale, in which an assessor has to use his judgement to decide a student’s score. What is also behind the use of tests is the wrong belief that language learning is shown when students memorize facts and knowledge. However, foreign language learning is mostly about developing the skills of reading, listening, writing and speaking.

DISTRIBUTION OF ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENTS ACCORDING TO LANGUAGE SYSTEMS AND SKILLS MEASURED

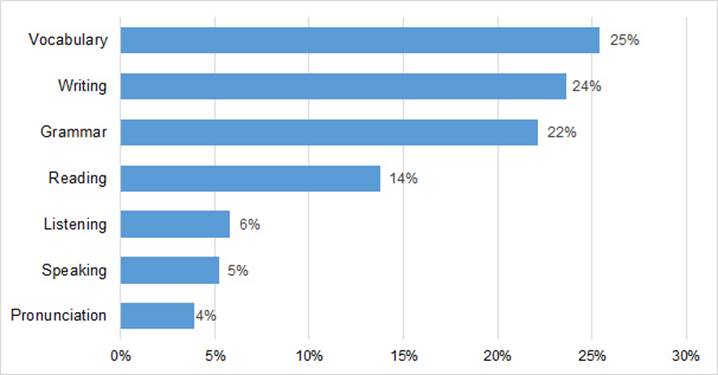

The distribution of language skills and systems measured reads as follows. From the 205 tests, 158 instruments assessed the writing skill, 92 instruments assessed the reading skill, 39 instruments assessed the listening skill, and 35 instruments assessed the speaking skill. Regarding the language systems, it has a frequency of 365. Vocabulary is included in 170 instruments, grammar in 148 instruments, and pronunciation in 26 instruments. It is necessary to remember that a test may contain not one but several language systems and skills to be assessed.

In Figure 2, the highest percentage of assessment instruments were oriented to vocabulary measurement (25%), followed by writing (24%) and grammar (22%). The least evaluated system and skill measured were pronunciation (4%) and speaking (5%), respectively.

In a sample of 205 assessment instruments, vocabulary is present in most of the assessment instruments, in 170 of them. This is equivalent to 25% of the total of samples of assessment instruments. This tendency of privileging vocabulary over other language systems and skills is explained by Kalajahi & Pourshahian (2012).

In their study, they state that there are many ways to learn English, however, if the teacher opts for a vocabulary learning strategy (VLS) teaching approach, the learners may gain different skills (reading, listening, writing, and speaking) in a better and simple way and thus, the experience of learning the foreign language will be better to the students and they will keep motivated to gain mastery in English.

Matsuoka & Hirsh (2010) complemented the idea that learning vocabulary helps to learn other skills, especially reading comprehension. In their work, they summarized the studies conducted by other experts in vocabulary learning strategies and concluded that before learning how to read using learning skills, there must be a threshold to hold on to before reading appropriately. This estimated 95% of the vocabulary lexicon needed to learn reading skills. The authors conclude that teachers must enforce vocabulary items in their class while using ELT coursebooks.

EDUCATIONAL LEVEL IN WHICH ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENTS WERE USED

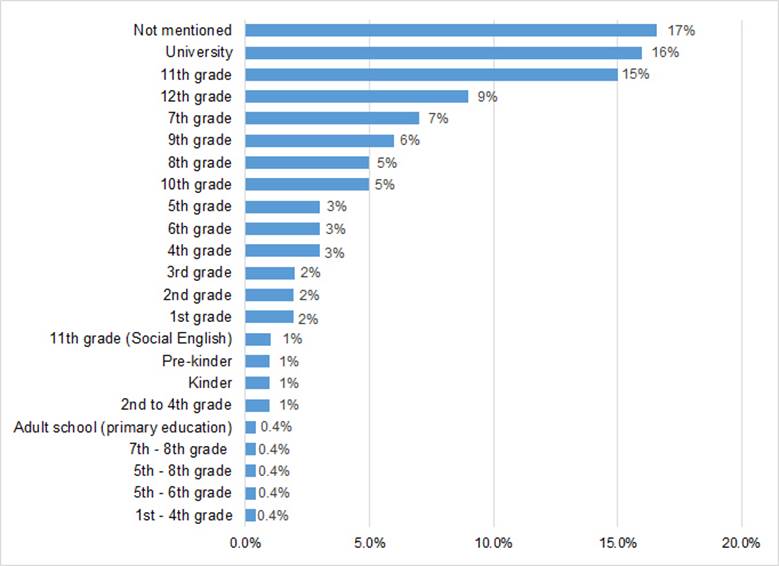

Regarding the grades in which these assessment instruments were used, this study covers all educational levels from 1st to 12th grade. Besides, there are plenty of instruments, which were also employed for kindergarten and prekindergarten students to university students and adult schools. These adult schools are educational establishments intended for adults who have not completed primary and/or secondary education.

Another special case is that some teachers used the same assessment instrument in different grades. The same numerical rating scale was used from 1st to 4th grade, without any changes in its content. The scale assessed the students’ English notebooks from 1st to 4th grade. Another case happened with a numerical rating scale which was used from 5th to 8th grade to assess students’ English notebooks, with no changes in their content.

These cases made a total of four assessment instruments which were used in eight different grades. Those cases are labeled in figure 3 below. Additionally, there were some assessment instruments in which the educational level was not mentioned, in those cases, the instruments were labeled as not mentioned.

From a total of 205 assessment instruments, 17% of the instruments did not mention the educational level in which they were used. Then, 16% of the sample was used in university levels, followed by instruments used in 11th grade (14%). On the contrary, the lowest percentage of instruments corresponds to instruments used from 7th-8th grade, 5th-8th grade, 5th-6th grade, 1st-4th grade, and adult school (primary education) by 0.4% (See figure 3).

Source: Authors own elaboration (2020)

Figure 3: Educational levels in which assessment instruments were used

Out of the 205 instruments registered, 17% did not include the educational level in which they were used. This happens because the instrument was used not only in one but different classes in the same school. This technique reduces the time available to create assessment instruments. Among all instruments in which the educational level is not included, tests are the ones in which the educational level is not clear.

Coltrane (2002) explained that with tests, it is more likely and easy to apply accommodation strategies. The different accommodation techniques allow teachers to adjust some features of the test such as scheduling by giving more time to a different class if their language level differs from other classes, and setting, if one class needs, a different location due to class size problems, to ensure that learners are in a comfortable place when they take the test.

NUMBER OF ITEMS

According to figure 4, the instruments composed of only 4 items have the highest percentage of the sample (21%). Then, it follows the instruments that have 5 (20%) and 7 (15%) items. It forms a pattern as the number of items increases, the percentage decreases. The lowest percentages are the instruments composed of 12 and 15 items sharing 0.4% of the sample.

SCORING SYSTEM INCLUDED IN THE ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENTS

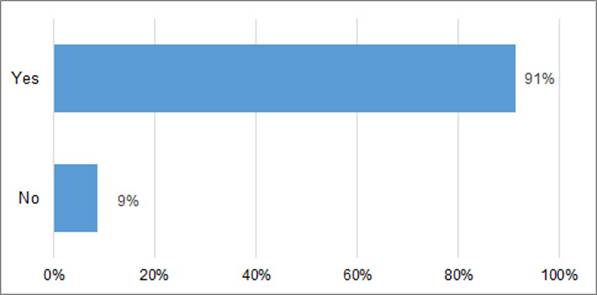

Figure 5 describes whether the 205 instruments included the scoring system as information for students. The vast majority of instruments showed the total score, specifically 187 instruments represented by 91% in figure 5. On the other hand, 9% of the instruments (18 instruments), did not contain any information related to the score.

LANGUAGE SYSTEMS MEASURED IN THE ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENTS

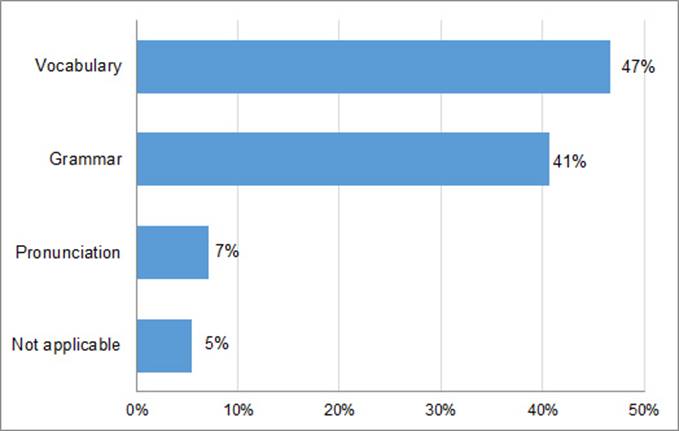

The assessment of the language systems was found in 205 assessment instruments. The language systems found in the instruments were vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation. Figure 6 below shows that vocabulary was measured in 47% of the assessment instruments. Then, grammar scored 41%, followed by pronunciation by 7%. However, 20 assessment instruments did not assess any of the language systems. These assessment instruments are in figure 6 below as not applicable by 5%.

TYPES OF ITEMS

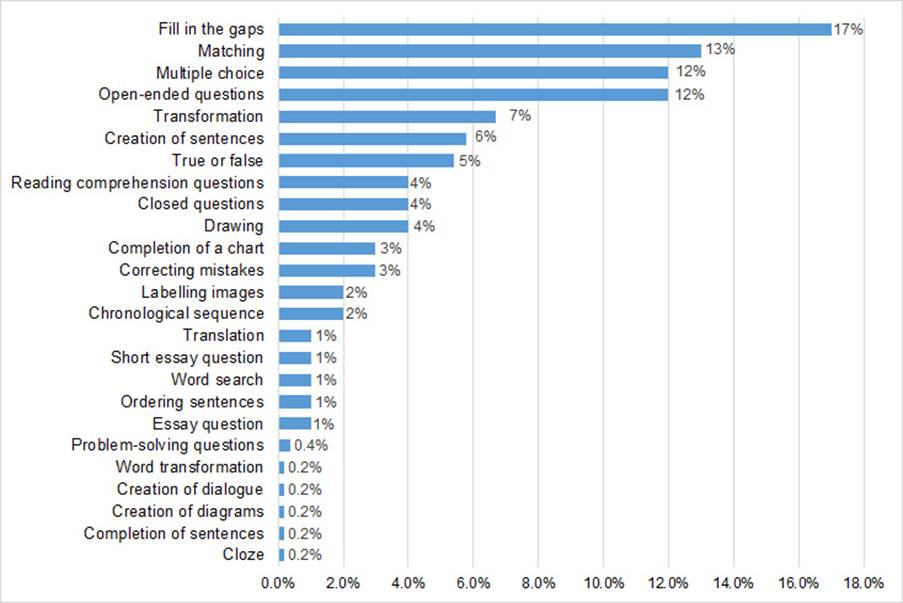

Among the instruments evaluated, it is possible to group them according to their type. For instance, Figure 7 groups the types of items used in Tests and Quizzes. The highest percentage among them is to fill in the gaps items (17%), matching items (14%), and multiple-choice items (13%). Word transformation items, creation of dialogue items, creation of diagrams items, completion of sentences, and cloze items share the lowest percentage by 0.2% (See figure 7 below).

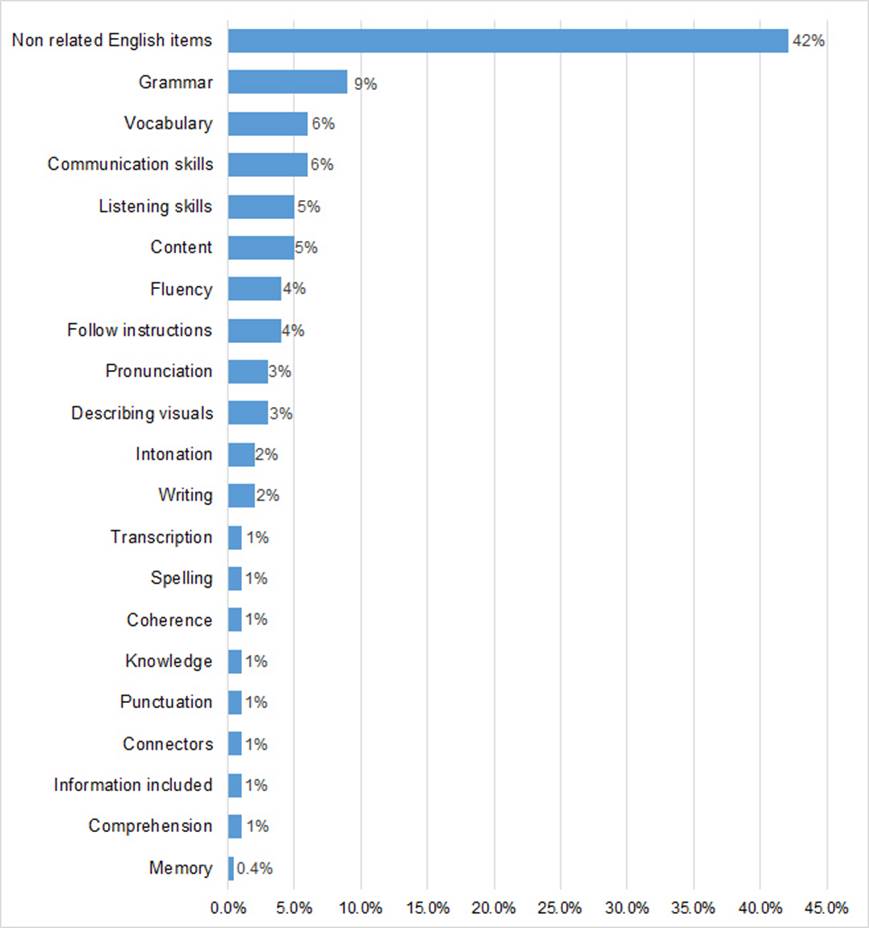

In Figure 8, there is another group composed of rubrics, rating scales, and checklists. There is an extensive list of different contents used in these types of instruments. The highest percentages of language content measured are grammar (9%), vocabulary and communication skills (6%), and listening skills and content (5%), whereas the lowest percentage of content measured is memory (0.4%). There is a group of contents measured in these instruments labeled by figure 8 as no related English items that include contents such as scenography, use of uniform, respect, presentation, participation, creativity, among others (see figure 8).

Source: Authors own elaboration (2020)

Figure 8: Language contents included in rubrics, scales, and checklists

The items most used in these assessment instruments were fill in the gaps (17%), matching (13%), and multiple-choice and open-ended questions (12%). These findings, as Frodden, Restrepo & Maturana (2009) explained, are related to the lack of time teachers have. Teachers have to look for more objective items that are easy to correct and design than more subjective tasks.

The items fill in the gaps, matching, and multiple-choice are related to the practicality principle as they are easy to create as well as easy to assess. For instance, multiple-choice items provide teachers with the opportunity to “quickly analyze the performance of each Test item and use this information to improve future assessments” (Scully 2017:4).

On the other hand, open-ended questions are the type of item that requires teachers to spend more time on its development and grading as “they are not questions that demand a single correct response” (Khoshsima & Pourjam 2014:20). Even though this type of item may demand more time from teachers to develop, teachers use it as this item can “improve the respondent’s possibilities to be heard and give accurate information” (Schonlau, Gweon & Wenemark 2019:2). It can test any aspect of the language, and it is beneficial to build it in the classroom (Dickinson & Tabors 2001).

According to Martínez, Salinas & Canavosio (2014), the assessment instruments aim to assess the organization, content, and accuracy of the tasks asked, such as an essay. However, the most assessed language contents were non-related English items, such as timing, use of uniform, creativity, respect, among others by 42%. It might be possible that Chilean teachers tend to assess students’ behavior to keep them on task, as Martínez et al. (2014) stated that teachers considered other criteria to assess such as students’ attitude, responsibility, and behavior.

Taking aside these types of contents, figure 8 shown earlier, reveals the most assessed language contents: grammar (9%), and vocabulary and communication skills (6%). Even though these results follow the hierarchy criteria of organization, content, and accuracy (Martínez et al. 2014), they also follow the other discovered hierarchy, which is content, accuracy, and then organization (Martínez et al. (2014) ).

CONCLUSIONS

Chilean English teachers prefer traditional assessment instead of alternative assessment. This was a clear tendency from the collection of the assessment instruments. Tests registered 60% predominance compared to the rest of the assessment instruments analyzed. For this reason, we can infer tests are the preferred language assessment instrument used by teachers to assess learners, with an amount of 124 instruments. Besides, the type of items that had the highest percentage through the assessment instruments was fill in the gaps items present in 17% of the assessment instruments.

The fill in the gaps items were encountered 89 times among the 205 assessment instruments. The assumption regarding the results is that Chilean teachers prefer traditional assessments and items that are easy and economical to create, correct, score and mark. However, even though teachers in this study were free to send any type of assessment instruments of their authorship, they might have also misconceived assessment instruments as only tests. Moreover, bearing in mind the lack of time, support, and even resources from the educational system, it is highly difficult for educators to find different ways of assessing learners.

Regarding the language systems and skills identified throughout this study, we can state that vocabulary is present in 25% of the assessment instruments and the most measured skill was writing with 24% of the assessment instruments. Both systems and skills measured were successfully identified in every assessment instrument.

In conclusion, the assessment instruments were mainly oriented to the assessment of writing skills and vocabulary, which were found in 158 instruments and 170 instruments, respectively. Teachers tend to use traditional assessment, which highlights the testing of vocabulary, grammar, reading and listening through traditional test items (fill-in the gaps, multiple choice, matching, etc.).

Nevertheless, it is necessary to assess English language in a more contextualized, integrated and meaningful way. This is not to say that traditional testing has to be demonized, but to suggest that language assessment should integrate traditional and alternative assessment tools that can maximize student learning