INTRODUCTION

Textbooks "seek both to stimulate language learning and to support language instruction" (Hadley 2018:298). In this sense, Tomlinson (2013:11) suggested connecting learning and instruction's current research in material development. That is, in order to create a course book that aims to foster language learning, it might be suggested to consider the opinion of experienced teachers (Wen-Cheng, Chien-Hung & Chung-Chieh 2011).

Textbooks should include authentic and pedagogical content (Burns 2012). In contrast, Ecuadorian public course books were unfitting for many students and did not meet most learners' needs (Espinosa & Soto 2015). In 2019, new educational textbooks were initially implemented in Ecuadorian public schools to comply with current EFL research.

The principles that frame the textbooks are:

Content and language integrated learning (CLIL), which is "an educational approach involving the use of foreign/additional language as a tool for instruction" and "creates a space for learners to become engaged in meaningful language use" (Nikula & Moate 2018:21).

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach which focuses on real-world contexts and engages learners in the authentic, functional use of language for meaningful purposes (Ministerio de Educación 2016:6)

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) establishes skills in the use of the English language based on students' context and ages (Fisne, Güngör, Guerra & Gonçalves 2018). It offers guidance for teachers, examiners, textbook writers, teacher trainers, and educational administrators (Ministerio de Educación 2014:6),

Moreover, the aim is to foster 21st Century skills such as social and thinking skills, a foundation for lifelong learning (Ministerio de Educación 2016) and focus on language use and production (Espinosa & Soto 2015:28).

These pedagogical modules were first used in the highlands and Amazon regions. The set comprised 72 modules, six modules for each of the twelve school years of primary and secondary education. Each module consists of 32 pages; it complies with the National Curriculum, the CEFR, and branches from the communicative approach. The pedagogical modules are distributed digitally. Likewise, it provides listening resources uploaded on the Ministry of Education website.

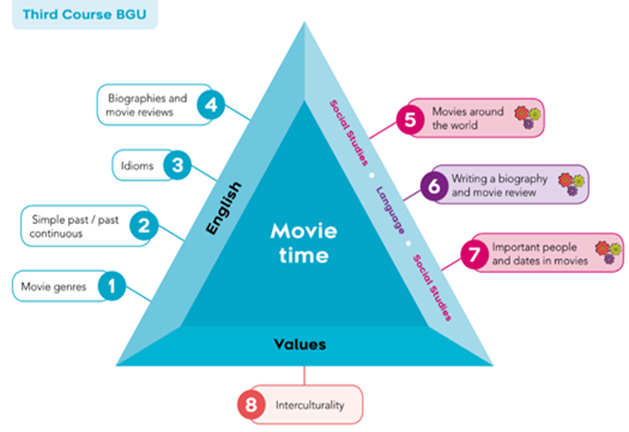

An example of the organization of a module is shown in figure 1. In the center of the triangle, the central theme of the pedagogical module is displayed. On the left side of the triangle, the topic and English skills for this unit are established. On the right side, the unit's connections with other subjects such as History, Social Studies, Science, Art, Language, Language and Literature, Art History, and Mathematics are addressed. Finally, at the bottom part of the triangle, the values that will be addressed in each unit are indicated.

Agreement on the role of textbooks in both teaching practice and learning has not occurred. Some teachers consider textbooks are an essential source of classroom activities; for teachers, the resource "saves time and effort in preparing for the lessons" for students, it gives them "an easy access to present and future content" and learners from different backgrounds have the same information (Ulla 2019:971).

However, some may rely on teachers' roles. Vellenga (2004:2) reported that "most textbooks are inadequate, but an effective teacher can overcome the shortcomings of a text." According to Wen-Cheng, Chien-Hung and Chung-Chieh (2011:94), course books work "as a supplement" to the teaching methodology and that course books should "provide the foundation for the content of lessons, the balance of the skills taught, as well as the kinds of language practice the students engage in during class activities."

The relation of teachers' attitudes towards textbooks is beneficial in course book development and may need further consideration. Kilickaya (2019) explored how teachers' contributions in evaluating a course book are valuable for teaching practice and learning experience. Ahmadi and Derakhshan (2016:265) concluded that developers should "pay critical attention to the materials arrangement, the vocabulary and grammatical points, language skills, language teaching methods, and the appearance of the book."

Although teachers' perceptions depend on their own teaching style, "no neat formula or system may ever provide a definite way to judge a textbook" (Ansary & Babaii 2002:1:8). For this reason, teachers' opinions are important in research in order to narrow down to criteria that appropriately evaluate the content and usefulness of the course book (Azadsarv & Tahriri 2014; Jayakaran & Vahid 2012).

Besides specifying what is to be learned, a

syllabus also signals how those contents will be learned and in what order. The organization of a syllabus signifies

which theory of language, learning, and language use it has adopted. The order of contents shows the underlying

principles for sequencing and grading.

Besides specifying what is to be learnt, a

syllabus also signals how those contents will be learnt and in what order. The organization of a syllabus signifies

which theory of language, learning, and language use it has adopted. The order of contents shows the underlying

principles for sequencing and grading.

Studies have shown some criteria that may serve as a starting point in course book evaluation. Al Mamun (2019:181) stated that the quality of editing and appropriateness for contextual settings are two essential aspects of course books: "specifying what is to be learned" and "how those contents will be learned and in what order." Some may hinder the importance of grammar presence and vocabulary extent, which depends on the students' level and attitudes towards the language (Namaghi, Moghaddam & Tajzad 2014).

Besides, students' needs should be considered; the effect of course books on students results in adapting their own learning styles, self-regulating, and selecting information to comprehend the texts (Beishuizen, Stoutjesdijk & Van Putten 1994:171). English textbooks should be relevant to the students' needs and interests in connection to meaningful activities (Ahour, Towhidiyan & Saeidi 2014:156). Texts should prepare "learners to overcome the problems they encounter in real life" (Dahmardeh 2009:49).

Teachers highly regard the implementation process and training of course books. Ebrahimi and Sahragard (2017) explained that even though current textbooks packages provide audio tracks, teachers' guides, and workbooks; EFL teachers may still have negative perspectives towards these new materials because of time constraints, lack of training, uneven activities among language skills and learner strategies, lack of destination culture and contextualized activities. Consequently, it is suggested that teachers are trained before using a course book to apply them effectively in their classrooms (Mili & Winch 2019).

Textbooks are the primary resource of Ecuadorian teachers in their classrooms (González et al. 2015:99). However, it is suggested to implement textbooks designed based on Ecuadorian reality and Ecuadorian curricular guidelines; consider cultural, social, and economic aspects; develop oral communication skills and meaningful knowledge (Lozano 2019:66).

In Ecuador, few pieces of research focuses on the perceptions that EFL teachers have on textbooks in their pedagogical practices. There is a lack of research dealing with the implications of integrating English language pedagogical modules in Ecuadorian EFL classrooms. Consequently, this study will explore the following results:

How do Ecuadorian EFL teachers working at state schools perceive the new pedagogical textbooks?

Which are the changes that Ecuadorian EFL teachers perceive in the new pedagogical textbooks established by the Ministry of Education compared to previous textbooks?

How do Ecuadorian EFL teachers working in state schools perceive the implementation of these new pedagogical textbooks?

This study is underpinned by previous research that explored teachers' perceptions of the content, use, and implementation of the textbooks in EFL education. The current study reports a qualitative study's method and results based on three qualitative techniques: a content analysis of the pedagogical modules, content analysis of the Ecuadorian national curriculum, and a focus-group interview with eight Ecuadorian EFL teachers. Thus, it recommends practical changes to make more efficient the integration, use, and application of these new Ecuadorian pedagogical modules.

METHODOLOGY

This investigation is based on qualitative research principles. It is principally based on a focus group interview conducted after a detailed overview of the Ecuadorian EFL curriculum and the Ministry of Education's pedagogical modules. In order to obtain data, the following considerations were made in the process:

1) selecting the instruments,

2) identifying the items in the instruments,

3) outlining the participants' selection, and

4) carrying out the study (Griffee 2005).

After examining the curriculum and the course books (pedagogical modules), data was collected from the semi-structured focus group interview participants, which was analyzed using content analysis.

PARTICIPANTS

The participants of this study were selected purposefully based on their understanding of the topic (Bolderston 2012). A total of seven Ecuadorian teachers from the Amazon, Highland, and Coastal regions participated in the focus group interview. All of them have experience in teaching English as a Foreign Language in Ecuadorian public schools. Six of them had used the pedagogical modules before the study; one teacher had not used them but had explored these pedagogical modules' content.

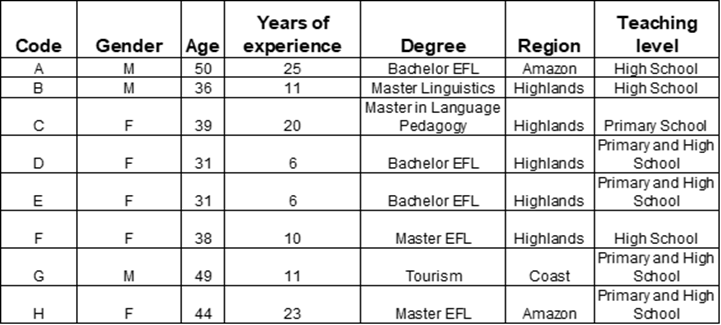

The background of the participants is reported in Table 1. Five teachers had six to eleven years of EFL teaching experience, and three teachers had more than twenty years of experience in this field. Three teachers hold a bachelor's degree in EFL teaching, four teachers have a master's degree in the English teaching field, and one teacher holds a bachelor in Tourism. It is essential to indicate that a professor of qualitative studies from a Hungarian university acted as a supervisor and consultant of this study.

INSTRUMENT

In order to obtain relevant data for this study, a focus group interview was carried out. According to Bolderston (2012), this type of interview should include five to ten participants; for this reason, eight teachers were invited to participate in this study. The interview included predictive (what the interviewee considers will happen) and retrospective evaluation (when the interviewee has already used the textbook) (Rahimpour 2013).

Another consideration for creating the interview is the nature of questions. Naba'h, Samak, and Massoud (2016) suggested categorizing teachers' perceptions before the study; thus, this was one of the first steps. For this, the authors revised previous checklists from other authors and decided on each question's importance based on literature findings. For example, López-Medina (2016) also developed a checklist to evaluate a course book; by using a checklist, authors would not forget any essential criteria if interviewees do not mention them and, thus, no time-wasting (Abdelwahab 2013).

The questions from the interview were adapted from and based on previous research methodologies. The criteria for creating the questions met specific general considerations from Rahimpour (2013) in analyzing a course book, such as skills appropriateness and integration, social and cultural considerations, and subject content. Other research is from Ansary and Babaii (2002, p. 6), who created a set of universal features of EFL/ESL textbooks, in which there was also a highlight to content and connection to current approaches.

The study also contemplated the suggestions of Mukundan and Nimehchisalem (2012) related to the adjustment to the learner's needs, the efficiency of audio materials, and cultural sensitivities (p. 1132). Furthermore, some questions derived from Rosyida (2016) outline who focused on the textbook's applicability to students' needs, the complication of its use, and its relation to the syllabus.

After creating the interview guide for the focus group, it was sent to a university professor who provided expert-judgment on this instrument. After making the suggested changes, the instrument was translated to create an equivalent instrument in the participants' L1 (Brislin 1970). The equivalence of the two versions was checked with the use of back-translation into English. The researcher piloted the interview with two Ecuadorian EFL teachers; this process helps determine the instrument's feasibility and limitations to refine its content (Creswell & Poth 2016).

The interview's implementation was a four-part process that included a formal welcoming to the meeting, the instructions, the questions and participation of the interviewees, and the closure (Mahmoud 2013). The first part of the focus group interview provided background information on personal details and teaching experience (Mukundan & Nimehchisalem 2012). The third part of the focus group interview consisted of asking about the integration of the new pedagogical textbooks, current teaching methodologies, and elements of the new textbooks.

The interview consisted of eight questions to be covered during the interview with follow-up questions to obtain a more in-depth understanding of the participants' answers (Legard, Keegan & Ward 2003; Suri 2011). The questions progressed from general impressions to an in-depth examination of the topics; this way, all essential items could be carefully explored (Abdelwahab 2013).

Specifically, participants shared their ages, level of education, region, and levels that they teach. The second part consisted of eight questions regarding general perspectives on the course book, activities' alignment to current methodologies, and specific perspectives on the content. The questions also referred to the pedagogic modules' relation to the National Curriculum Guidelines (Ministerio de Educación 2014).

The protocol followed other focus-group interview guidelines (Bolderston 2012). The author and the co-author as a co-facilitator hosted the interview. The hosts ensured that all participants were contributing equally, with specific verbal signaling. The meeting was online; the setting of the video conference via Zoom permitted the face-to-face connection required.

Participants were informed of the topic and the type of questions they would need to answer concerning the pedagogical modules. Participants were informed that their names would be changed to pseudonyms and not shared with external parties to maintain confidentiality.

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

Primary data was collected from the first-hand-experience of the interviewees (Kabir 2016). The interview was recorded live through the Zoom video conference program. During the interview, questions arose on behalf of the hosts/authors, and some clarifications were made when needed. Similarly, this study is underpinned by a system for coding the interaction in focus group interviews (Morgan & Hoffman 2018).

The recruitment of the interviewees was made by phone. The authors explained the aims of the study and the personal and candid nature of each question. The participants were informed about how the meeting would be held and recorded and that the information provided would be solely used for research intentions.

Essentially, a code has been assigned to participants in order to maintain the citing standards. According to ethical considerations protocols, the interviewees were given a code and are referred to as teacher + letter. This process abides by confidentiality agreements among the participants and hosts of the interview, that is, in this research, the authors.

The authors clarified the anonymous aspect of the process and received the consent of all active participants. In other words, the teachers that did not agree to the terms and process were not included in the present study. In order to avoid bias, the researchers neither commented nor participated in the interview. Additionally, the questions were revised by an external assessor as well as sent to other fellow teachers. This last procedure was permitted to verify that meanings and phrases were correctly transmitted to the reader.

Data were analyzed by transcribing the audio through a voice recognizer and monitored by the transcriber, one of the authors. The second author revised and oversaw the transcription in order to avoid missing information. During the third and final revision of the transcript, the authors worked online to add their annotations.

In a shared online document, the data was analyzed by building topics and codes based on a constant comparison of data, codes, and emerging categories (Kelle 2010). The final topics were classified upon each category, and comments matched the same ideas with different connotations, depending on the interlocutors' opinion.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The present section includes the topics that emerged during the focus group interview. It covers an analysis of teachers' perceptions of the implementation, use, and integration of the pedagogical modules provided. According to Ansary and Babaii (2002), teachers' criteria may differ from one another; for this reason, this study contrasts the patterns and aligns the common ideas obtained from the participants' answers.

For research question 1, How do Ecuadorian EFL teachers working at state schools perceive the new pedagogical textbooks? Teachers reported limited compliance with students' needs in terms of length, level, and skills. Textbooks are required to include various metacognitive activities that foster students' learning outcomes (Dahmardeh 2009).

Some of the teachers indicated that the content was too difficult for students from rural areas with a low English level due to learners' backgrounds and low prior knowledge. Some of the disadvantages derived from detecting that the activities focused on a few skills. Teachers also described the inability of students to reach the textbook's level.

One of the course books' failures is that they ignore the integration of four language skills in the same amount throughout content and activities (Ahmadi & Derakhshan 2016:265). Teachers stated that the modules aimed at improving reading and writing but missed on more listening and speaking activities. For example, Teacher D (personal communication, April 20, 2019) manifested dynamic activities but focused only on reading comprehension.

Other teachers defended that the writing activities in the pedagogical textbooks displayed several types of texts, which may help students learn the skill through varied opportunities to perform. For instance, Teacher F (personal communication, April 20, 2019) claimed that he likes the tasks that the course books offer texts like how to write e-mail or essay, for example. On the other hand, all the participants agreed that activities that foster the use of four skills (listening, writing, reading, and speaking) should be incorporated in course books, as well as that the four skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) need to be included in the same extent.

A practical course book "has just the right amount of material for the program, it is easy to teach, it can be used with little preparation by inexperienced teachers, and it has an equal coverage of grammar and the four skills" (Richards 2001:2). Learners' interests should be considered in selecting reading texts for an ELT textbook since they can affect students' language learning (Namaghi, Moghaddam & Tajzad 2014:125). Besides, topics and activities that help students develop high oral communication skills and meaningful knowledge must be included (Lozano 2019:68).

The length affected another issue, which is teaching time. Teacher A (personal communication, April 20, 2019) reported that the course books' content is too extensive, so much so that it cannot be covered in the school year. Teacher C (personal communication, April 20, 2019) thinks it would be better to reduce some of the activities because there is much content. Similarly, Teacher F (personal communication, April 20, 2019) expressed that information is too extensive and broad.

For research question 2, Which are the changes that Ecuadorian EFL teachers perceive in the new pedagogical textbooks established by the Ministry of Education compared to previous textbooks?

Participants stated that there were some issues in transitioning from previous course books to the new modules, not only in getting the document but also in the lack of training.

Teachers need to be informed of and familiar with the textbooks. "prior to selecting a textbook, educators should thoroughly examine the program curriculum" (Wen-Cheng, Chien-Hung & Chung-Chieh 2011:94). The previous books were grammar-based, and suddenly, the course books were loaded with new methodologies and text-rich tasks that seemed too much for them. Teacher A (personal communication, April 20, 2019) expressed that if they were going to make this kind of transition, we, as English teachers, should have been the first to know.

The experience of students was different at each level. For younger learners, it was incredibly complicated; Teacher C (personal communication, April 20, 2019) stated that her students of the seventh year were learning the simple present tense last year, and now the new texts include all the past tenses, for the kids, it would be terrible.

In high school, most teachers explained that the material is aligned with the students' level. However, a few teachers had a different experience. For example, Teacher H (personal communication, April 20, 2019) indicated that some students in the Amazon region, unfortunately, have had no English classes before. Our findings contrast with Nikula and Moate (2018) advice, who claimed that using the language should be done gradually to obtain better improvements in the second language. Additionally, the situation contrasts with CLIL principles that aim for English to become "a habitual part of the classroom environment" (Nikula & Moate 2018:23).

Participants evaluated some of the features of the modules positively. The main positive point was that the document provides students opportunities to communicate and use the language authentically. The positive commentaries observed communicative principles. First, Teacher E (personal communication, April 20, 2019) stated that the way one learns is by doing, and the positive aspect is the authenticity of the activities; none is repeated. Teacher B (personal communication, April 20, 2019) said that the course books help students develop critical thinking. In this sense, communication is the main goal in current teaching practice, and that the modules fulfill it.

The new text book adhered to the principles advocated in the National Curriculum (Ministerio de Educación 2014). Participants mentioned that there is a link to CLIL in activities and focused on topics rather than grammar rules. These findings are supported by Nikula and Moate (2018), who defined CLIL as an opportunity to use the language and learn it to understand other disciplines.

For research question 3, How do Ecuadorian EFL teachers working in state schools perceive the implementation of these new pedagogical textbooks? On this matter of teacher training, a few participants referred to the modules' arrival and application as a disaster. Teacher B (personal communication, April 20, 2019) indicated that the transition of these new pedagogical modules was the most challenging aspect that teachers have to face, and it is the reason it affects us. As Ulla (2019) explained, teachers, in general, have positive perceptions of using textbooks as an essential source in their classes; however, if teachers are not adequately trained, they will attain negative perspectives towards new course books (Mili & Winch 2019).

That is why it is essential to allow teachers to control the curriculum at the classroom level to meet students' needs in a better way (Espinosa & Soto 2015:40). According to the participants, they did not receive any training before using the modules. A few teachers were trained, but only after finishing the school year.

We were surprised when we received the new pedagogical modules, we did not have any idea about these new books, and because we did not receive any training, we had to find information from other sources such as a Facebook group of Ecuadorian English teachers or colleagues from other institutions. (Teacher F, personal communication, April 20, 2019)

Regarding receiving the material, all of the teachers had significant delays during the school year; while classes started in September, the modules arrived in November. In this regard, Teacher C (personal communication, April 20, 2019) indicated that he had been using the previous textbooks, even after the arrival of the new modules, because the integration of these new modules was a significant change, and it was shocking."

Likewise, Teacher E (personal communication, April 20, 2019) explained that when the information of the new textbook arrived at our institution, we already planned and presented the Annual Curriculum Plan for all the classes we had to teach during the year, so we had to do double work. This emerging comment provided a general perspective of how this process was perceived:

The integration of these modules was a disaster for teachers since we only obtained these modules in a digital form, we did not have the audio materials, and even worse, we had no idea about what to tell the parents and students who already had the previous textbooks. (Teacher E, personal communication, April 20, 2019)

It could be the case that EFL teachers have negative perspectives because of time constraints, lack of training, uneven activities among language skills and learner strategies, lack of destination culture, and contextualized activities Ebrahimi & Sahragard (2017). Although "textbook writers should provide students with a variety of exercises and activities to practice language items and skills" (Richards 2001:4), it is essential that teachers are trained (Richards 2001:6) to use course books to apply them as a useful guide in their classrooms (Mili & Winch 2019).

There is a recommended strategy to using textbooks, "teachers should be able to respond to these new challenges and changes by altering activities and creating the more tailored ones" (Wen-Cheng, Chien-Hung & Chung-Chieh 2011:95). It is relevant to revise and modify the English books, which may imply removing or changing unsuitable material and proving the books' quality (Azadsarv & Tahriri 2014; Jayakaran & Vahid 2012).

Furthermore, it is essential to understand that "every textbook needs adapting every time it is used because every group of learners is different from every other and has different needs and wants" (Tomlinson 2012:272). According to Teacher G (personal communication, April 20, 2019), it is now up to us, teachers, to demonstrate that we can make it with these new modules.

Teachers agreed that the lengthy content was one of the main challenges, but they would either edit or delete some content and activities that they cannot cover because of the lack of time. Participants decided to use only some of the readings from the modules in every given lesson, while the rest covered some of the pages and created their own sequence. Teacher F (personal communication, April 20, 2019) sustained that teachers are undoubtedly forced to make adaptations, select topics, and cover the skills required by the syllabus.

Adapting not only implied changing the materials but also deleting. Teacher D (personal communication, April 20, 2019) claimed that textbooks have good topics, but most of them cannot be included in classes because of their complexity. The majority of the teachers manifested that they deleted or omitted some content from the pedagogical modules. The decision to adapting content is crucial, given that "using textbooks that do not match the needs and goals of both teacher and students could result in failure in teaching and learning the English language" (Ulla 2019:971).

In addition, some of them indicated that they adapted their practice to the communicative features of the modules. Teacher B (personal communication, April 20, 2019) expressed that every course book, well, it is excellent because there will be some learning. These comments align with the findings of Rosyida (2016), who claimed that teachers create tasks and materials based on students' needs and adapt. According to Ansary and Babaii (2002) and Ahmadi and Derakhshan (2016), teachers' perspectives on the books they apply in their everyday practice help them gain insight into making changes seeking a more efficient use of the materials.

In this sense, participants shared solutions and decisions made at the core of their English departments. Some teachers added that modules provided an excellent opportunity to adapt and apply current methodologies.

CONCLUSIONS

From this study, it is possible to conclude that even though Ecuadorian EFL teachers identified strengths and weaknesses in the pedagogical modules, they positively evaluate them. They indicated that the new pedagogical modules provided teachers and students meaningful activities and authentic materials to use in their teaching-learning process. Besides, they stated that the new pedagogical modules are connected to the Ecuadorian curriculum and the current ELT methodologies, such as project-based learning, learner-centered approach, and CLIL. Other positive features that teachers perceived were contextualizing the content and integrating current teaching topics to foster students' English skills.

On the other hand, teachers listed some weaknesses in these pedagogical modules. All of the teachers perceived that these modules lacked sequence; they were not addressed to the English level that students had, they mostly focused on reading and writing skills, and they were expected to cover them quickly.

In terms of integrating these pedagogical modules, all of the interviewees agreed that the transition from the old textbooks to the pedagogical modules was a failure. They mainly did not have any training before implementing them in their classrooms, and they only obtained parts of the modules digitally. Furthermore, there are still missing pedagogical modules, such as audios and teachers' guidebooks.

Some teachers highlighted that the previous textbooks had grammar-based sequences, which contrasts with the new communicative nature of the modules. Those who argued for the importance of integrating skills commented on other elements in creating these modules. There were comments on the urge to step up in the teaching practice.

Based on these findings, there are a few recommendations. For instance, experts in charge of creating and editing EFL pedagogical modules may consider integrating the same amount of content to the four primary English skills. Besides, to align and connect all pedagogical modules' content and provide formal training and enough resources to integrate these new pedagogical modules efficiently in EFL classrooms.

Another recommendation is that it is essential to consider this aspect, given that learners "pay more attention in class when the content is meaningful" (Espinosa & Soto 2015:42). In a similar study, teachers commented on interaction fostered by the activities and reported that the course book is practical when it "facilitates authentic interaction" (Hadley 2018). However, the role of the teacher affects this matter. A textbook is often the essential resource, but "there are other materials that teachers may use or adapt so that students feel engaged in developing listening and speaking skills" (Gonzalez et al. 2015:100).

To conclude, it is suggested to explore course book evaluation further to obtain more findings. Research is essential through questioning the use of textbooks, "which have been used by experienced teachers who, after making informed choices about the needs of their learners and the concerns of their specific pedagogical context, are actively engaging students in the task of learning" (Hadley 2018:304)