Introducción

In social work, a social science discipline, research depends on reliable and relevant information with which to generate knowledge and seek the most suitable solutions.In schools delivering courses on social work the debate on academic research training and professional practice is ongoing, as these endeavors are deemed to contribute to social emancipation and the elimination of inequality and exclusion. In Spain the degree is geared to the skills demanded by employers (Molina, 2009).

Social workers must be conversant with issues affecting citizens. In addition to professional competence, they must master the information skills that enable them to introduce social change (SCONUL, 1999; Association of College and Research Libraries, 2000, 2016).

The study discussed hereunder was designed to determine the information skills that should be acquired by future social workers during their university training, based on the inclusion of information literacy (IL) in the curriculum.

Literature review

ACRL (2000; 2016) defines IL to include the recognition of when information is needed, the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced, the ability to locate, evaluate and use effectively the information needed, the use of information in creating new knowledge, the ethical participation in communities of learning and the application of critical thinking to build knowledge.

CRUE-TIC/REBIUN [Spanish university library network] (2012) establishes ten areas comprising IT and information skills: 1.- access to vehicles; 2.- access to protocols; 3.- digital identity; 4.- operating systems and resident software; 5.- internet and the web; 6.- university websites; 7.- information search; 8.- information assessment; 9.- organizing and communicating information; 10.- keeping abreast of and sharing information. These areas are implicit in the information skills defined by the network (CRUE/REBIUN, 2014).

Gómez and Hernández (2013) study the integration of IL in the curriculum, contending that these skills are the key to preparing students for study, the working world and personal life. The implementation of ongoing, coordinated IL in curricula and full collaboration between educators and librarians advocated by those authors is shared here.

Marzal and Borges (2017) deem that the four types of skills - effective content consumption, effective content creation, interaction and metaliteracy - regarded as features of academic excellence must be integrated in and form part of IL indicators in structure-based skill evaluation.

Toledo and Maldonado (2015) 44-item measuring tool is based on UNESCO standards for information and communication technology (ICT) skills for educators and on the rules on aptitudes for accessing and using information in higher education. It also addresses the knowledge and use of and attitudes toward devices, tools and services. Cabezas, Casillas, Ferreira and Teixeira (2017) deem that those items also help determine university students’ digital skills.

Undergraduate social work courses stress the acquisition of research and intervention skills. The global standards for social work education and training set out by the IASSW/IFSW (2004) include nine sets of standards that serve as a reference for universities to formulate their curricular offering.

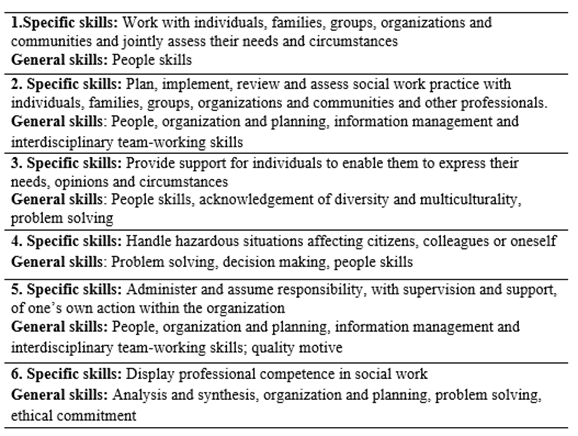

The profile of specific and general skills defined for the degree in this area offered in Spain and summarized in Table 1 draws heavily from those precepts (Vázquez et al., 2005).

Table 1 Specific and general professional skills by group.

Source: Adapted by the authors from Vázquez et al. (2005)

As the table 1 shows, there are six groups of specific professional skills, each associated with one or several general skills. Spain’s Libro Blanco de Trabajo Social [white paper on social work] divides the profession’s objectives into three groups: competence objectives: know-how (aptitudes); discipline objectives: mastery (knowledge) of curricular subjects; and attitudinal objectives: command of conduct. A flair for interpersonal communication when gathering information, either for research or intervention might have profitably been included as another objective under command of conduct.

Metodología (Materiales y métodos)

This descriptive study adopted a quanti-qualitative approach and was conducted in two stages. The first consisted in information searches in the Web of Science, which yielded 101 papers, and Scopus, where 104 were retrieved. The terms (and all their possible combinations) searched included information literacy, international information literacy standards, information skills, information competence training, social science, social work, higher education, information literacy indicators and information skill measurement. In the second stage a proposal for information literacy standards was established for use in the profession.

The documentary analysis performed covered the ACRL's Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (ACRL, 2000), Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (ACRL, 2016), Information Literacy Standards for Anthropology and Sociology Students (ACRL, 2008), Political Science Research Competency Guidelines (ACRL, 2008) and Psychology Information Literacy Standards (ACRL, 2010).

The CRUE/REBIUN (2014) definition of information skills, the Global standards for the education and training of the social work profession (IASSW/IFSW, 2004) and the skills listed in Spain’s Libro Blanco de Trabajo Social (Vázquez, et al., 2005) were also analyzed.

The standards formulated were submitted for review by two groups, one comprising eight social workers and the other eight information scientists, who replied to a questionnaire designed to assess the skills defined. The Liker scale used was: 1 (very important), 2 (important), 3 (neutral), 4 (scantly important) and 5 (unimportant).

Resultados

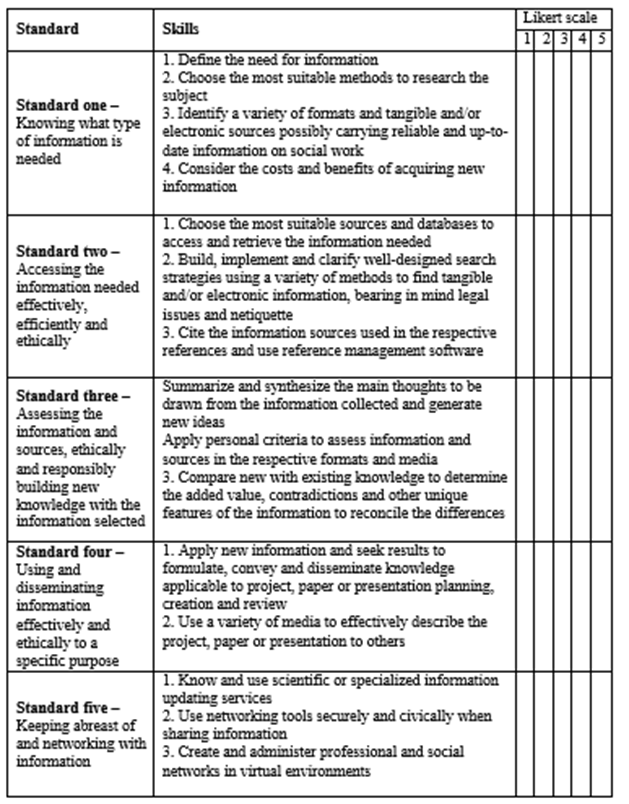

Questionnaire. The questionnaire reproduced in Table 2 lists the five IL standards and their associated skills derived from the documentary análisis.

Standard one was deemed important by 88% of the social workers and the other four to be very important by 100%. All five standards were regarded as very important by 100% of the information scientists. In light of the results, all five information literacy standards were included in the proposal.

Discusión

Information literacy standards for social work

Standard one: knowing what type of information is needed

Skills. 1. Define the need for information

Indicators: a.- Identify and describe a research subject or area or other information need characteristic of social work, using specific terminology, methods and contexts. This entails the ability to conduct exploratory searches in general information sources and references to acquire a command of the subject. Documentary sources typical of social work and other more general references such as encyclopedias and dictionaries may be used.

b.- Identify and list keywords and their synonyms for information searches on the subject. Encyclopedias and dictionaries may be used.

c.- Formulate the research subject, determining search parameters in keeping with the need for information: timeframe, geographic scope, depth.

d.- Ascertain the scope of the information retrieved and determine if the information needs must be clarified, revised or redefined after a preliminary exploration of the literature on the subject.

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors.

e.- Understand that up-to-date and authoritative scientific information is needed to conduct research.

f.- Realize that duly qualified social workers should be consulted to precisely define the subject to be researched.

g.- Constantly rethink the nature and scope of the information required.

Skills 2.- Choose the most suitable methods to research the subject

Indicators. a.- Identify and assess the qualitative and quantitative methodologies applicable to social work that related to the problem or project at issue. Examples: fieldwork, participant observation, data analysis, interviews, survey-based research, literature review and databases specific to the specialty.

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors. b. Have a working knowledge of institutional policies on research involving individuals, including access to participants, their consent and the institution’s requirements. c. Identify and analyze privacy, confidentiality, security and other ethical issues relating to the research methodology used, further to the principles laid down in social workers’ codes of professional ethics.

Skills 3. Identify a variety of formats and tangible and/or electronic sources possibly carrying reliable and up-to-date information on social work

Indicators. a. Describe how the information used in social work is generated and formally and informally disseminated. Examples: censuses conducted, ethnographies, field notes, datasets, conference papers, grey literature, academic websites and peer-reviewed academic articles.

b. Realize that social work knowledge is organized in ways and formats that may affect access and evaluation. Examples: academic journals, article databases (Dialnet, Google Scholar, SciELO Citation Index); e-book databases (Openedition Books, Google Books); repositories (BASE, SocArXiv, Recolecta, RecerCat, OAIster, Oxfam Policy and Practice); research databases (CIS data bank, Harvard Dataverse, International Data Archives, re3data.org); dictionaries (IATE - InterActive Terminology for Europe, Diccionario de servicios sociales); dissertations (Tesis doctorales en red, Teseo, NDLTD Global ETD Search, Open Access Theses and Dissertations, DART-Europe E-theses Portal); congresses (Agenda SiiS, Congresos - iS+D, Calenda, Conference Alerts); bodies and institutions (CIS - Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Emakunde - Instituto Vasco de la Mujer, Instituto de la Mujer y para la Igualdad de Oportunidades); organizations (IPES Mujeres y feminismos, SiiS Centro de Documentación y Estudios); and statistical portals (CIS - Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Eurostat, Human Development Reports, UNESCO Institute for Statistics); and mailing lists (Listas RedIRIS - Ciencias sociales), to name a few.

c. Differentiate between primary and secondary sources in social work, acknowledging the use and value of each. Examples: (primary sources) the academic journals cited in point b; (secondary sources) dictionaries, encyclopedias, yearbooks and similar.

d. Realize that existing information can be combined with original thinking, experimental studies and/or analysis, generating new information and different perspectives on social and cultural developments and social theories.

Skills 4. Consider the costs and benefits of acquiring new information

Indicators. a. Determine the availability of the information required and broaden the search with resources not found in the university library or on line. Example: borrow documents from another library; correspond with students in other universities to gain access to information in databases subscribed to by their university but not by one’s own.

b. Define research timing: timetable for gathering the information needed, doing the fieldwork, analyzing the data...

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors. c. Use open access information to address social work issues

Standard two - Accessing the information needed effectively, efficiently and ethically

Skills. 1. Choose the most suitable sources and databases to access and retrieve the information needed

a. Identify and select information relevant to the subject in library databases and catalogues, bearing in mind the format: scientific journals, monographs, dissertations. Example: review the social science citation index and choose a journal suited to the subject researched.

b. Distinguish among information resources on the grounds of typology, utility, location and nature (general or specialized). Differentiate between databases furnishing indexed and up-to-date information in journals, books, dissertations and conferences on social work and others furnishing on-line text from other less visible or less recent journals on other disciplines, depending on the study under way.

c. Access academic material available on specialized websites published by organizations such as the Consejo General de Trabajo Social (https://www.cgtrabajosocial.es), Asociación Internacional de Escuelas de Trabajo Social (https://www.iassw-aiets.org/), Biblioteca Virtual de la Escuela de Trabajo Social de la Universidad de Costa Rica (http://www.ts.ucr.ac.cr/biblioteca_v.php), Centro de Documentación e Información sobre Trabajo Social (https://www.siis.net/es/que-es-siis/presentacion/1/), Federación Internacional de Trabajadores Sociales (http://ifsw.org/) and Red Eurolatinoamericana de análisis de trabajo y sindicalismo (http://www.relats.org/). Websites should always be assessed to the following criteria: author qualifications, audience, currency, editor, reliability, objectivity, relevance, scientific rigor and utility.

d. Understand when it is advisable to access different resources and tools. Example: use Google Drive to store and share on-line information; use specialized search engines to access over 80 million PDF files with scientific papers, such as http://www.freefullpdf.com/; http://www.scienceresearch.com/ for scientific subjects and http://www.kiosco.net/ for newspapers and magazines.

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors e. Be conversant with and observe university rules and regulations on accessing information resources and storing texts, information, images, field notes and audio-visuals.

Skills 2. Build, implement and clarify well-designed search strategies using a variety of methods to find tangible and/or electronic information, bearing in mind legal issues and netiquette

Indicators. a. Use social work-appropriate terminology in database searches, applying keywords, synonyms and vocabulary from one’s own database lists and thesauruses such as published by UNESCO.

b. Design effective search strategies in different social work databases using advanced search tools, Boolean operators, stemming and filters to define searches precisely. c. Use search engines to find books, academic journals and electronic sources

Skills 3. Cite the information sources used in the respective references and use reference management software a. Understand and distinguish among citations, bibliographic references and a bibliographies. That entails the ability to cite the sources used and reference them appropriately.

b. Recognize different types of citations depending on the source: books, articles, dissertations, websites, illustrations, audio files. That calls for distinguishing different types of documents in the references.

c. Realize that citation rules vary by discipline and publisher: APA, ISO, Chicago, MLA, others. The ability to follow citation and reference rules must be acquired.

d. Master cloud and desktop reference management software and be able to create a database using reference managers such as Zotero, Mendeley, RefWorks or ENDNOTE.

e. Understand how to import and export reference data from and to reference managers. That entails reusing the information obtained in bibliographic searches to import and export references between reference managers and texts using reference management software.

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors. f. Understand that sources must be cited to respect authors’ intellectual property and know how to distinguish between paraphrase and quote. g. Understand the benefits of technology for drafting and organizing references and citations.

Standard three - Assessing the information and sources, ethically and responsibly building new knowledge with the information selected

Skills. 1. Summarize and synthesize the main thoughts to be drawn from the information collected and generate new ideas

Indicators. a. Identify the main ideas in texts (books, academic papers, interview transcripts, ethnographies), select theories, conceits, analyze, synthesize, interpret quote or paraphrase information.

b. Recognize inter-relationships among concepts, social theories and field observations and combine them to build new knowledge.

c. Use electronic tools and specific software to access reliable information sources and contribute to virtual team collaboration.

Skills 2. Apply personal criteria to assess information and sources in the respective formats and media

Indicators. a. Review and compare information from various sources to ascertain its validity, relevance, perspective and the author’s qualifications.

b. Recognize that not all the information available on line is relevant and reliable and that sources must be assessed to determine their suitability for the work at hand.

c. Seek different points of view in alternative databases, books, websites, digital repositories and articles, evaluating the source of information or reasoning and determining whether or not to include the opinions put forward.

d. Analyze argument structure and logic and whether the methodology is in keeping with social work standards, identifying the most judicious ideas and possible conclusions.

e. Recognize and interpret the cultural and material contexts in which information was created.

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors f. Identify and discuss problems associated with citizens’ social rights in accordance with internationally accepted standards.

Skills 3. Compare new with existing knowledge to determine the added value, contradictions and other unique features of the information to reconcile the differences

Indicators. a. Store the information retrieved in organized files and determine if it meets research needs; if insufficient, select other information that furnishes relevant supporting evidence, deploy other search strategies and draw new conclusions based on the information compiled.

b. Seek expert opinion from social workers and similar professionals through interviews, e-mail, mailing lists, fora, chatrooms and virtual communities to validate and interpret information.

Standard four - Using and disseminating information effectively and ethically to a specific purpose

Skills. 1. Apply new information and seek results to formulate, convey and disseminate knowledge applicable to project, paper or presentation planning, creation and review

Indicators. a. Organize and integrate content, quotes and paraphrases in ways that support document or presentation purpose and format.

b. Acknowledge the difficulties encountered and adopt alternative strategies to integrate new and existing information and create knowledge by formulating a project, document or presentation.

c. Have a working knowledge of the various types of academic and technical papers: senior’s theses, oral communications, posters, videos, research projects, dissertations, articles, essays.

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors d. Understand what plagiary means.

e. Contribute to teamwork.

Skills 2. Use a variety of media to effectively describe the project, paper or presentation to others

Indicators a. Choose the medium, format and style best suited to the document and target audience (blogs, websites, social networks, e-mail, chatrooms).

b. Use a range of formats and technologies, including design and communication principles, to present a research project, choosing the medium, type of dissemination and format best adapted to the document and audience: open-access platforms or commercial vehicles.

c. Distinguish the most common digital and hard copy publication identifiers: ISBN, ISSN, legal deposit, doi, PURL and similar.

d. Sign papers with a standardized signature.

e.- Design and manage websites for communicating and disseminating electronic documents.

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors. f. Understand conceits such as intellectual property, copyright, open access policies and technology transfer, making proper use of documents. Obtain permission from authors or organizations where copyrighted material must be used in presentations or texts.

g. Share research outcomes with netiquette-respecting groups that use social work information ethically.

Standard five - Keeping abreast of and networking with information

Skills. 1.- Know and use scientific or specialized information updating services

Indicators. a. Keep up-to-date with alert services, site summaries (RSS) and similar tools, networking, managing a digital profile and interacting in a specialized or general social network.

b. Use virtual and collaborative tools to organize the information received (wikis, blogs, microblogging, fora).

Skills 2.- Use networking tools securely and civically when sharing information

Indicators. a. Share and communicate information with collaborative tools and social networks such as audio and video channels, virtual tools for creating and sharing documents, social bookmarkers and personalized virtual environments.

b. Use a personalized virtual environment to organize and share information, observing digital environment conventions and rules of conduct.

Skills 3.- Create and administer professional and social networks in virtual environments

Indicators. a.- Further e-collaboration and the exchange of ideas.

b. Lead virtual teams, assign tasks and responsibilities to meet targets.

Ethical, socio-cultural and legal dimensions and behaviors. c. Understand the risks of sharing information on line and maintain a suitable digital identity.

d. Evaluate the relevance of the information disseminated and shared, avoiding spam and infobesity/infoxication.

Conclusiones

The standards described facilitate the introduction of IL in social work curricula to help undergraduates develop information, digital and info-communication skills, while strengthening teaching-learning in the field and specific and general professional skills. Each standard covers knowledge, aptitudes, attitudes and behaviors that students need to acquire. These skills and their respective indicators can be used to evaluate students and encourage their own self-evaluation. The ethical, socio-cultural, netiquette-related and legal dimensions and behaviors listed help them measure their performance in the use of information, an area of vital importance in social work, from the perspectives of both research and professional practice.