Introduction

The city is a human settlement which does not date back to modern times, but has its roots in the great civilisations of long ago, particularly the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilisations. In the past, it was referred to as a “city”, from the Latin “civitas” which means a highly organised group.

The Urban programming began when architecture began and had been working in a broad field of study. For this reason, the fabrication of cities published books, articles, magazines, and topics in a wide range of study, in different methodologies.

Up to now, there are many diverse definitions of urban planning and many methods approaches. The urban planning is defined as a process to investigate and decision making that identifies the scope of work to be designed (Neiler, 2015). In other words, urban programming means the inquiry, observation, questionnaire, investigation, interview, discussions (Ma, 2015). That is to say, it is the process of describing the real condition, gathering the information, client’s requirements, uncover the design problem, analysis, synthesis of the relevant data of project which clarifies the objectives, to facilitate the design decision making (Deng & Poon, 2013; Van der Voordt & Van Wegen, 2005; Hassanain & Juaim, 2013).

The normative rule is an indispensable tool for forecasting and regulation, and its role is essential in the planning and management of the city. However, it has always been criticised. The city is a human settlement which does not date back to modern times, but has its roots in the great civilisations of long ago, particularly the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilisations. In the past, it was referred to as a “city”, from the Latin “civitas” which means a highly organised group (Mangin & Panerai, 1999). In addition to its inadequacy and inefficiency, the scarcity of financial resources induced by the economic crisis of the 1970s, and the inability of the welfare state to finance planning and construction projects. All of these facts have incited the public authorities to value cities economically and to revise urban planning theories in depth (Carrière & Demazière, 2002). Thus, urban planning of norms has been replaced by urban planning of projects.

The project, or more precisely the urban project, is a concept that was developed by the Italians. It is the result of the symbiosis of two disciplines: architecture and urban planning (Masboungi, 2002). The project conceived within the framework of a federative plan requires an approach which is essentially based on the implication of several actors (Martin & Novarina, 2003). Project-based urbanism or concrete actions were expressed in the 1980s and 1990s by a multitude of large urban projects, first in the United States of America and then in Northern Europe. As for the cities on the northern shore of the Mediterranean, they have recently resorted to these emblematic projects, their objective being to become more competitive and more attractive (Carrière & Demazière, 2002). In explaining these discussions, regional scientists offer various schools, theories and models. Scientists, with the use of descriptive and quantitative methods, attempt to institutionalize the urban system and optimal size of the city (Molaei Qelichi et al., 2017). Some Maghreb countries are not left out.

Among the Maghreb countries, Algeria is on the way to implementing this new urban planning approach. Following the example of the large Algerian cities, Annaba (36°54′15″N, 7°45′07″E) has been concerned in recent years by large-scale projects, namely transport infrastructures, large housing programmes and structural equipment. The majority of these projects have been completed or are underway, while others have been put on hold. However, what merits attention is that among these projects there are those that were not provided for in the urban development plans, which forced the local authorities to launch a revision of these plans. The most remarkable example is the project of 1400 houses in the forest area of Sidi Achour. Another fact that needs to be mentioned is that of the tramway. This means of transport, much coveted for its cleanliness, its capacity and above all its dynamising effect on the city, has raised an outcry in civil society. This protest against its layout, which was to pass through the hyper-centre, was not its contribution to the city, but it did allow for the emergence of associations paying attention and interest to the urban space, and activating through public debates and writings. This societal consciousness had a favourable echo among the local authorities, who decided to suspend the project while waiting for a common agreement on its layout. Thus, the will to resort to an urbanism of image to shape emblematic projects, the non-conformity of the project in relation to the plan, the submission of the local authorities to the claims of the civil society as for the realization of certain projects, and the awareness of the citizens, all these facts constitute an observation which pushes us to wonder if the urbanistic practices in gestation in Annaba are really revealing of the adoption of a new urban rule for the manufacture of the city.

Faced with emergency situations, among other things, the urban planning instruments that were supposed to serve as a reference for programmatic actions (PDAU: Master Plan for Development and Urban Planning) and to regulate land use (POS: Land Use Plan) have proved to be obsolete. In fact, this approach has now reached an impasse in a context marked essentially by globalisation and the shrinking of public resources. The urban project is the solution adopted by the decision makers in Annaba for the construction of the city.

2. Methods

Like all other disciplines, urban planning heavily depends on research to grow and evolve. Without this the discipline can lose relevance and become extinct in today’s fast-changing world (Odongo & Donghui, 2021). The study of the urban process is one of the main contents of urban planning. It concerns the socio-economic interrelations between the city and its environment, and this must be reasonably organised using favourable instruments and urban rules.

The urban programming is one of the major important stages of planning and design. Urban projects process frequently is still missed in urban development or confused with tasks of urban development planning (Rohani & Ma, 2018).

The research methodology undertaken in this article is both a historical and analytical. The choice of the historical approach is motivated by the fact that it is necessary to have recourse to history because it allows us to find clarification in the origins of the past (Spiga, 2004). As for the analytical approach, it consists of observing phenomena that raise questions and lead to the formulation of hypotheses that are nothing other than anticipated answers to be verified. The reasoning followed is deductive, based on prior knowledge and previous experiences, which allows for analysis and goes beyond the simple observation of facts.

The method adopted can be described schematically as follows:

After the theoretical research, it was necessary to proceed with the exploration of the documents concerning the terrain. To do this, tools were used, in particular plans and photography. The adopted investigative approach consisted in tackling the large scale and then the small scale. That is to say, to undertake an analysis of the documentation concerning the study area (the site), then the case study (the project).

To understand the methodological aspects of the work, it is essential to master the concepts used. To do this, we approach terms such as “project”, which etymologically refers to an old French word: “pourject”, which designates the work of an architect. Nowadays, this meaning has been extended to encompass devices that are part of human productive activity, the realisation of which is not a certainty but can be envisaged (Pinson, 2000).

It was not until the 1990s that the notion of urban projects took on the dimension it has today, following the appearance of wastelands in urban areas as a consequence of the economic crisis or decentralisation. Indeed, these reclaimed lands have a high land value and have been given projects to make them profitable, however, without the prior elaboration of an overall plan. The proliferation of these projects has resulted in urban disorder, functional inconsistencies, spatial imbalances and social inequalities (Berezowska, 2012).

Thus, Tomas François specified that with the urban project, the architectural object lost its status of autonomy that it acquired in the modern period, and was reinforced by weaving relations with its context (Tomas, 1995).

According to Patricia Ingallina, the urban project, which was already in fashion in the 1970s, has been used by architects as a synonym for urban composition, to which they also associate the idea of a large-scale architectural project. In other words, the notion of the classical ‘project’, which belongs to the domain of the architect, prevails over that of ‘urban’, which refers to the city and involves a multitude of competences (Ingalimna, 2010).

On the question of the history and memory of cities, Devillers, like other theorists and professionals, is particularly interested in them. He believes that the urban project cannot be designed outside the city, but within the existing city, taking into consideration its history and the elements of its urban form and their relationship (Devillers, 1994).

After this preliminary work, it was important to have an idea about the use of the urban design rule in the world (Toussaint, 2003). Examples of cities were chosen, namely Bologna in Italy, Barcelona in Spain and Montpellier in France. This choice is not fortuitous; Bologna has the merit of having given birth to the concept of the project and/or the urban project. It has served as a model for many countries in the world. Barcelona is not to be outdone. Indeed, since the early 1980s, this capital of Catalonia has become a laboratory of urban planning from which the decision makers can learn.

As for Montpellier, it is a city which has been equipped with a multitude of urban projects which contribute to the attractiveness of its territory. Furthermore, we chose to compare these three Mediterranean cities with Annaba because they have experienced strong demographic growth since the middle of the 20th century.

These examples of cities are useful to establish a comparison in terms of urban management with the case study of Annaba. To do this, structuring projects realised or planned in this city were studied, comparison criteria were selected and analysis grids were drawn up to confirm or infirm the use of the urban project rule in Annaba. This work ended with recommendations by way of conclusion, while identifying research perspectives.

2.1. Bologna, a landmark experience

The first study area is Bologna, an important Italian city and the capital of the Emilia Romagna region. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400.000 inhabitants, with a density of 2,817 persons/km2 (ISTAT, 2019). Bologna is considered the origin of the urban project. In fact, it is in this city that the urban project was born and developed with the experience of “recupero”. The urban project has its origins in the debates and theories that broke away with the rational and modern thesis, which were held in Italy in the 1960s. It is an innovative procedure which advocates a plural approach to acting on the city and which has implemented, in addition to negotiation, consultation, social mixing, public/private partnership and neighbourhood councils (Pinson, 2006) Furthermore, it is important to specify that the use of the project has not excluded the use of the normative rule (the plan) to frame the projects. However, it has been made more flexible for possible readjustments.

The Bologna experience has become an essential reference for Europe. In Great Britain, for example, regeneration of neighbourhoods and urban wastelands was carried out in the 1970s and 1980s. In France, where technocratic urbanism and state planning reigned in the 1960s and 1970s, a new form of intervention began in the centre of Paris with the Les Halles operation. This project was intensely debated and publicised by the press. Exchanges and criticism led to progressive adaptations.

2.2. Barcelona, the city of partial urban projects

Barcelona is the capital of the autonomous community of Catalonia of Spain and the second-largest city in Spain with a population of 1.7 million, with a density of 16576 inhabitants/km2 (IDESCAT, 2020). It has become a Mediterranean capital as a result of the will of politicians, elected representatives and urban planning professionals. These actors have adopted a strategy that advocates urban planning that is both local and event-based. Thus, specific operations (local projects and emblematic projects) have transformed the city’s landscape to further improve its image, in particular to make it more attractive and to strengthen its economy (Sokoloff, 1999). As in Bologna, the project approach in Barcelona was based essentially on consultation, partnership and public consultation. The projects carried out were also marked out by the rule of the plan which presents only the main development orientations.

To requalify the periphery, which is made up of large housing estates, the Eixample de Cerdà was taken as a source of inspiration, hence the use of the closed block and the creation of spaces of urbanity and sociability. The Barcelona Olympic Village project, in terms of both the design and the method used, presents an interesting alternative.

2.3. Montpellier and the French urban project

Located between Marseille and Barcelona, Montpellier is one of the most attractive cities of the Mediterranean coast. It is an important city in the South of France. In 2018, 290,053 people lived in the city, with a density of 5196 inhabitants/km2 (INSEE, 2019), Its central district was concerned in 2002 by a major operation called “Grand Coeur”, whose objectives are to revitalise the central area, to ensure a harmonious and equilibrated development of the city (centre and periphery), to improve the living environment of the inhabitants of the centre, to maintain a social diversity, and to make the city more attractive. To achieve this, tools were implemented, notably partnership, consultation and participation. The projects carried out have been framed by the rule of the plan and the local housing programme.

A balance is sought for all the districts of the city centre. Each district must offer its inhabitants a pleasant living environment, ensure social diversity and allow the sharing of public space. The operation aims to improve the living environment in the centre to satisfy not only the residents but also the new inhabitants. It was also a question of revitalising the economic, commercial and service activities, crafts and offices, while making the centre accessible to all users. The historic centre has been extended and its heritage has been renovated.

3. Results

Annaba is a littoral city located in the north-east of Algeria. Having been endowed with innumerable potentialities, it has always been coveted and even conquered. It has seen several civilisations and dynasties pass through it, leaving traces that time has taken care to preserve (Derdour, 2013). This inherited cultural heritage, associated with its exceptional natural heritage, constitutes a basis which makes this city a definite tourist destination. However, the urban rule adopted to manage the development of its urban fabric since the departure of the colonists until today is in reality only the result of a voluntary socio-economic policy.

Source: interest.co.uk/pin/barcelona-hotel-map--754282637561402284/ (2022)

Figure 3: The districts of Barcelona

Source: https://docplayer.fr/59214926-Le-perimetre-de-montpellier-grand-coeur.html (2022)

Figure 4: Montpellier

This is in contrast to what is applied in the other cities selected for comparison. Thus, the city of Bologna is widely recognized for an innovative regulatory framework to enable urban commons (De Nictolis & Iaione, 2021). The approach followed by Barcelone is different. This city is today a benchmark for many cities that aim to develop new sectors that generate jobs (Pareja-Eastaway & Piqué, 2022). In France (Montpellier), legislative power, supervision and control are still in the hands of the central State, with increasing input from intermunicipal authorities (Perrin et al., 2018).

And everything that is related to the urban question is relegated to the background. The primacy of the economy over urban planning has consequences for the city and its future. Today, global changes, such as the rise of image-based urbanism, digitalisation and the evolution of society, have prompted policy-makers to introduce large-scale projects for the country’s fourth city, in accordance with the SNAT orientations (Ministère A. T. E., 2010). Their aim is to resurrect the “coquette” and make it a metropolis or a “world city”. Among the major projects registered, the Sheraton Hotel, the Shopping Mall and the Port Terraces have been chosen to illustrate the present work. This choice is mainly justified by their location in strategic sites: the hypercentre and the outer harbour. The global study of these examples, as well as those of European cities, has enabled us to fill in comparative tables whose comparison criteria were determined from data collected in the theoretical part and which essentially concern the definition of the urban project as well as its tools.

4. Discussion

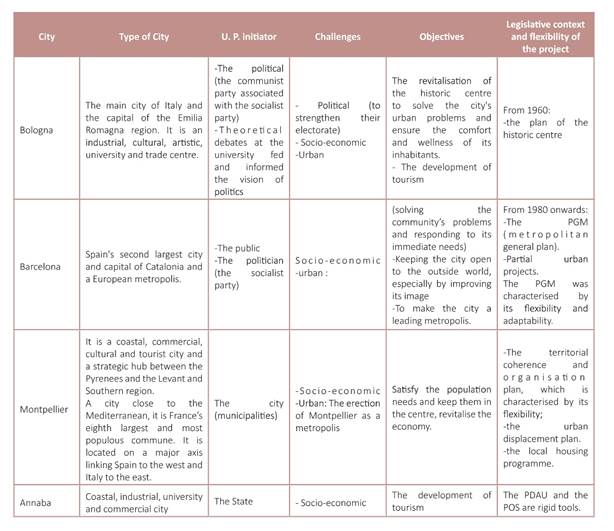

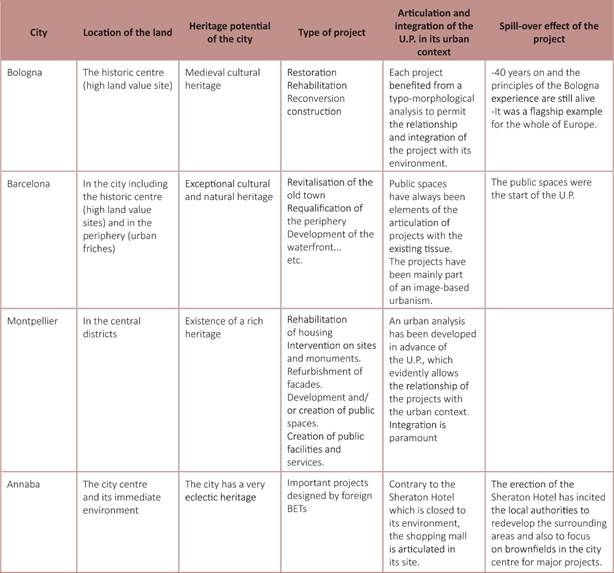

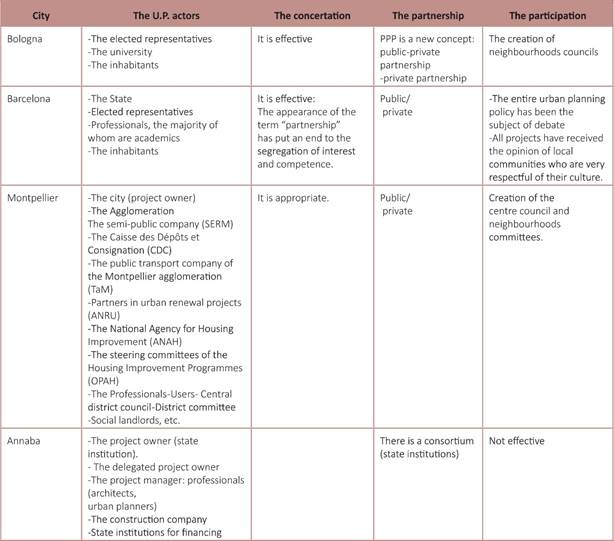

A careful reading of the criteria for comparing the three tables led to the following results:

Like the three European cities, Annaba is also a city that is not lacking in importance due to its innumerable potentialities. It is a port, touristic, industrial, commercial and university city. It also has a considerable natural and cultural heritage. These assets open up perspectives and facilitate the identification of economic, social and urban development issues. These strategic issues allow the actors of the public order (the initiators of the projects: the State as in the case of Annaba or the municipalities, or the population and the elected representatives exceptionally in Barcelona) to set objectives within the framework of a previously drawn-up urban policy. However, the legislative framework differs from one city to another.

For the three European cities, the regulatory framework governing urban development is essentially made up of plans or federative schemes which give the major orientations of development and which are essentially characterised by their flexibility. On the other hand, Annaba is still at the stage of classic planning tools which are rigid (Table 1).

The project sites in the three European cities as well as those in the city of Annaba are located in urban areas with high land values urban and often with heritage value. The projects in the European cities include several operations such as rehabilitation, conversion and redevelopment of public spaces. These projects are respectful of the cultural heritage, integrate harmoniously with the sites and articulate with the existing buildings. Some of them are designed to make the city more aesthetically pleasing and more attractive and competitive. Also, these projects frequently have a knock-on effect; in other words, they can trigger a real urban project that develops over time. The projects of the city of Annaba are rather punctual projects. They were designed by a foreign design office in a modern style in order to embellish the city and make it more pleasant and attractive (Table 2).

The data in the third table show that the projects realised in European cities are real urban projects. These are processes which bring together a multitude of actors and Table 3: Basic criteria of the urban project Source: Authors (2022)

which use all the procedures that are essential for the project approach, namely concertation partnership and citizen participation. As for the case study, it is in fact projects initiated and carried out by the central state or public institutions (Table 3).

This confirms that the project approach should not be copied from what is done elsewhere, but adapted to local conditions. Moreover, critics are beginning to surround it and are already calling on theorists to improve it (Picard, 2014).

5. Conclusion

A critical reading of the three tables mentioned above shows that most of the criteria, particularly the basic ones, namely consultation, partnership and participation, are not fulfilled in the case of the city of Annaba. Therefore, it can be concluded that the present research work, which was elaborated to confirm or infirm the hypothesis posed in the problematic, shows that the case study (the city of Annaba) is still at the stage of traditional planning. However, a new tendency related to an image urbanism is emerging, announcing the premises of the urban project.

The city of Annaba is an example that illustrates the use of the plan rule to manage urban growth. Struck by obsolescence, this normative rule still in force has shown its limits. However, changes in the social and economic context have shifted it towards a new trend announcing the premises of the urban project.

The urban project was born in Bologna as a process on the scale of the district, and over time it has been reformulated into a city project, or even an agglomeration project.

Although the urban project as a process has achieved unprecedented success, it tends to deviate from its original principles as a tool for urban form. In addition, the city projects have led to an atrophy in the participation of citizens, which is one of the basic foundations of the project approach.

This is why it is not interesting to reproduce what is done elsewhere, but to learn from the experiences of others so that the urban project remains a tool for democracy and, above all, for the urban form.

The use of the urban project does not exclude the use of the plan rule.