Introduction

In the past, personal values and freedom were neglected in Iran in various ways. Examples of this neglect are seen in Iranian architecture and urban planning that reflect the culture of their society. While a home is a place for resting and mental space and a shelter for the family and emotional needs for everyone. Home as private is a modern invention. Medieval homes, for example, were public spaces in myriad senses: full of people and used as public meeting places. Privacy for individuals within the home in that era was also nonexistent, with up to 25 people living in one or two rooms within a dwelling(Dowling, 2012; Knoblauch, 2020; Saunders & Williams, 1988). As Davidoff and Hall (2018) pioneering account shows, home as private was a product of a realignment of economic, political, moral, and spatial orders through the later parts of the eighteenth century. Here, for the middle class, home and dwelling were reinterpreted through the lens of separate spheres: a spatial moral and gendered separation of the world into collective life (public) and personal life (private) (Dowling, 2012; Gleadle, 2007; Somerville, 1997). Imagining a range of private syntaxes till public relations in a place that’s actually private is possible. But this range in the traditional Iranian homes focused more on the relation of households with others than the relations between each other. In contrast, the private realm of the home is typically understood as a space that offers freedom and control (Darke, 2002), security (Dovey, 1985) and scope for creativity and regeneration(Ahrentzen, 1997; Leith, 2006; Saunders, 1989). It is a confidential space that provides a context for close, caring relationships which was mainly introduced into Iranian homes as a result of religious beliefs. Traditionally, the confidential space is viewed from the aspect of privacy and it is a kind of family space.

As Porteous (1976) has pointed out, “at the core of the ethological concept of territoriality lies the place we call home. We personalize and defend this territory, and it, in turn, provides us with security, stimulation, and identity.” (p. 84) That home is a private space or realm is one of the key meanings of home. Feeling at ‘home’ is not just a function of being located inside a physical structure, but points to an emotional and social process that is very closely tied to cultural context. Yearnings for home and a sense of belonging are intimately connected to our understanding of community, family, and national identity. In defining the privacy of home, it is also often treasured or sentimentalized as a place outside the world of work and the formal economy. The contrast with public is hence central to the definition of private (Dowling, 2012; England, 2010; Gorman-Murray, 2012; Jacobson, 2012; Lloyd, 2012). This understanding of home is founded on several related ideas, most obvious among them, the distinction between public and private, and the inside and outside world (Mallett, 2004; Wardhaugh, 1999). The contours of home as private can be usefully delineated through reference to definitions of private(Chapman & Hockey, 1999, 2002a, 2002b). According to Macquarie Dictionary (2017), for example, private means (1) one’s own, (2) individual, (3) confidential, (4) not holding public office, (5) out of public view, and (6) not open or accessible to people in general. Each of these subtle definitional differences is inflected in home as private: (1) a site to own; (2) a site for the individual rather than the collective; (3) a space for intimate, confidential relationships; (4) a space that is not politics; (5) a space secluded behind fences, walls, hedges, and hence away from the gaze of others; and (6) a space with restricted entry without invitation. In broad terms, then, home is a site, and a set of relationships, that fosters the individual and his/her interests rather than those of the collective (Dowling, 2012). As summarized in a paper by Mallett (2004), home as private denotes that it is a familiar realm, removed from public scrutiny and surveillance. Home offers a space of freedom and control for the individual, and for intimate, caring relationships.

The longest research tradition in urban planning has, nevertheless, examined the home as home (residence) or homeplace (dwelling), and tended to privilege a physical structure or dwelling, such as a home, flat, institution, or caravan that is bounded in space with certain functional, economic, aesthetic, and moral structure(Atkinson et al., 2009; Blunt, 2005; Peil, 2020). Critical studies on the material realm of the home indicate that home is created by many cultural, economic, and social factors. The materiality of home is examined in its physical characteristics and existence as an object in space and time built up by material things(Chevalier, 2012; Liu, 2021; Smith, 2012); How people make and use spatial configurations, in other words, an attempt to identify how spatial configurations express a social or cultural meaning and how spatial configurations generate the social interactions in built environments(Griffiths, 2017; Refaat, 2019; van Nes & Yamu, 2021). In this research, we try to understand the material cultures of the Iranian home as a social construction by examining the spatial patterns and territories. Such an Identification can lead to the formation of more creative and culturally home spaces in Iran. The study consists of the following parts: First; the methodology of research, second; a definition of the concepts of home syntaxes and their features. Then, different spaces of Iranian traditional homes are identified and analyzed, and finally, the most important concepts of the material cultures of the Iranian home are discussed.

Methods

The research has been implemented in a grounded theory-based study and based on the content analysis method. A qualitative sampling including field observations, plans, documents analysis and interviews has been considered for a detailed knowledge of the material cultures of the Iranian home. The meaning of content in content analysis is all kinds of documents that suggested the relations between people. According to this, the paintings on the wall of caves, music, books, articles, handwritings, postcards, films, maps, direct and indirect observations, are included in the content (Banks, 2018; Flick, 2018).

In qualitative field research, the qualitative sampling which is also known as purposeful sampling or theoretical sampling (a sample approach) has been used. The sample size is determined by the “theoretical saturation” of the contents, the culture and context of the case study. Saturation means that no new and important content is obtained and the themes are well developed in terms of features and dimensions (Hennink & Kaiser, 2020; Kyngäs & Kaakinen, 2020; Lambert, 2019; Low, 2019). An open interview with 5 experts in the fields of architecture, urban design, and planning was conducted in addition to field observations of selected case studies.

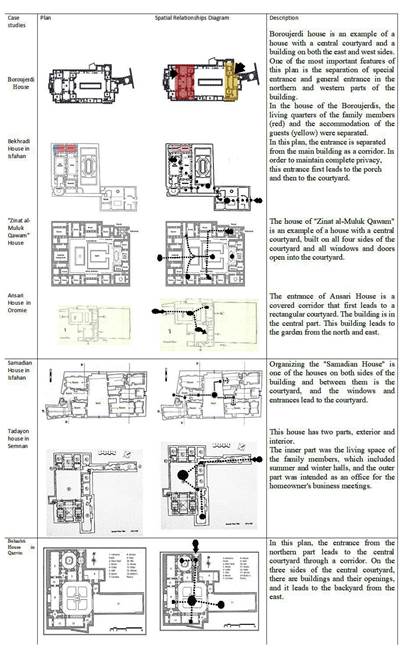

A grounded theory-based study is one that is derived directly from the data and contents collected and analyzed on a regular basis during the survey. The collected contents, analysis, and final theory are all tightly related in this process (Chamberlain-Salaun et al., 2013; Salvini, 2019). The qualitative analysis method consisted of 3 phases. In the first phase, the classes of the material cultures of the Iranian home are identified. Then, in the second phase, first, we studied some main documents and texts of Iranian homes, and then arranged 5 open interviews with some experts in the field of architecture, urban design, and planning Iranian traditional homes to reach theoretical saturation. One of the most important questions in the interviews was, could you please mention some Iranian Traditional houses that completely introduce the material cultures of the Iranian home, since two of the houses should be selected to conduct the research as an intensive research based on an indepth grounded interpretation of the material cultures of the Iranian home. Therefore, based on the opinions of 5 experts, a list of 7 houses was prepared, including Boroujerdi Home, Bekhradi Home in Isfahan, Zinat alMuluk Qawam Home, Ansari Home in Oromie, Samadian Home in Isfahan, Tadayon home in Semnan, Beheshti Home in Qazvin. The plan of these houses and their spatial relationships diagram are provided and examined in table 1. Then, two of them were selected and studied in detail. In the third step, selective coding and core category of the material cultures of the Iranian home in three main classes including, house forms (architectural patterns), activities (behavioral patterns), and cultural values is done and cultural reading is discussed and concluded.

Accordingly, trying to answer these questions:

What are the main cultural values of the material cultures of the Iranian homes?

What concepts are used in the material cultures of the Iranian homes?

What activities (behavioral patterns) do the material cultures of the Iranian homes have?

What are the house forms (architectural patterns) of the material cultures of the Iranian homes?

Results

Canter (1997) believed that the meaning of place is due to the triple relationship between activities, concepts, and physical features. Then for developing his theory, he points to four factors, including functional differences, the aims of a place, interaction scale, and design aspects. The functional differences are related to current activities in place. The aims of a place and interaction scale are related to personal, social and cultural aspects and designing aspects are related to physical features (Cupers, 2017; Gustafson, 2001; Sebba & Churchman, 1983). Hence, for investigating the material cultures of the Iranian home which aims to understand their basic concepts, we should consider activities and physical contexts which activities for what purposes take place in different spaces. There is variation in types of the material cultures of the homes across the world. The private territory is constituted by a collection of elements whose number, form, color, and function differ from one society or culture to another and are transformed during time (Boccagni & Kusenbach, 2020; Chevalier, 2002; Chevalier, 2012). Therefore, it is clearly constituted through a material context that is both social and cultural. It is where individual identities are expressed for sure, but collective identities too; society is integrated into private territory through the context of a home. This means that the public and private realms cannot be strictly separated, but rather interact concretely via things that enter and circulate within their subject worlds in order to secure its development and reproduction. At the same time, something more abstract is going on: social structure and organization belonging to the public realm insert themselves and are reinterpreted in the private realm in the form of the material cultures of the home(Chevalier, 1999, 2014; Cieraad, 2006). Individuals translate their public or collective experience into an inner arrangement of objects. Relations between a person and their society, community, kin, and friends are mediated by the world of objects: they give material expression to people, events, or places. These objects have no essential significance in themselves. Individuals endow them with meaning. Despite being stamped with the universal context of production and distribution that gave them provenance, there is always scope for their possessor to redefine what these objects mean. As a site for expressing our individual and collective identities, the material cultures of the homes open up a window on everyday life, on personal and shared history, and on our relations with others, whether close or distant, including the living and the dead.

Examining the results of studies and research in the field of architecture, urban design, culture, and interviews conducted, we can point out the factors that affect the creation of the material cultures of the Iranian home (shown in Table 2). These factors are: ritual and religious factor, climatic factor, perceptual and cognitive factor.

In the following, the appearance of these values and principles in the spatial body of the Iranian homes should be identified. This can be useful for the promotion of the modern material cultures of the Iranian home.

3.1. Analysis of Traditional Iranian Homes

Generally, there are 5 syntaxes in each home: personal, intimate, greeting, facility, and courtyard syntaxes. These syntaxes have special hierarchies in the Iranian traditional homes. Iranian homes separated homes into two parts: inside and outside. One of the features of homes in most of the cities of Iran is their large area. The important parts of the home are: bench, entrance, vestibule, balcony, courtyard, hall, parlor, and inside (Memarian & Brown, 2006; Memarian & Sadoughi, 2011; Nabavi & Ahmad, 2016).

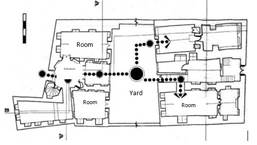

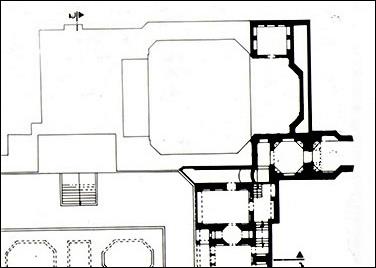

According to Figure 1 which is an example of a traditional plan, we can understand the concept of confidentiality, obedience and submission in its true meaning. Buildings are on both sides and the yard is between them. The entrance leads to the yard. Samadian’s House has three porches. Because of the privacy of these rooms, they don’t have a direct entrance from the yard and a corridor is provided for each entrance. In general, the structure of homes is meant to keep the private space for residents. In the past, large families didn’t have enough space to dedicate an individual room for each person and family members had to share rooms at home. For this reason, family members couldn’t easily find a place to be alone.

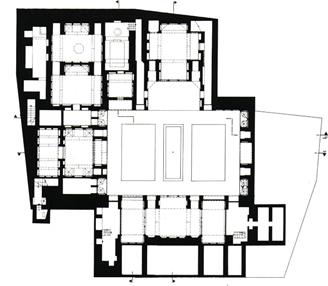

In Figure 2 (Boroujerdi’s House), separating the entrance path and also closing the corridor of view from outside to inside and creating a porch and frontage with platforms for guests waiting has been done in order to create privacy, confidentiality, humility and collaboration in the central courtyard. Boroujerdi’s house has three entrances: the north entrance is the main, the west entrance is for religious and other ceremonies and the south entrance is for specials. The opening only leads to the courtyard and a complete wall without any window or view from outside shows the importance of this issue (Figure 2 & 3). The space of the family members (red section) is completely designed separately from the guest’s room (green section) and the central courtyard is located in the center (Figure 3).

Also, sometimes, two types of percussion (Figure 4) have been used at the entrance to differentiate the sound until the owners realizes that a guest is a man or a woman.

It should be noted that Iranians from ancient times, according to their perception of home, have shown a tendency to introverted architecture. Basically, in the forming of urban areas, especially residential areas, the material cultures of Iranian constructions have been effective. One of these is continence, which has been effective in forming an introverted home. And also, one of the principles that affected vividly in forming confidential territories is the matter of introversion. Introversion is a concept that was a principle in Iranian architecture and with obvious presence in various ways is realized and seen (Nari Qomi & Momtahen, 2020; Raviz et al., 2015).

Introversion itself originated from territorial behavior. The society factor that causes introversion in Iranian homes is the issue of protecting the inviolable privacy of the family away from the eyes of strangers and contentment. Being quiet, a tendency to inner states and avoidance of pretension are the examples of being introverted in Iranian architecture, which appear in the form of tortuous passages, mud and soil walls and simple buildings from outside but the beautiful and detailed interior design (Razavizadeh, 2020; Safarian & Azar, 2020). Creating confidential spaces induces introversion. Therefore, the character of introversion in Iranian traditional homes, in which the family and spiritual beliefs have special respect, has been completely compatible with the culture of society. Pirnia (2005) in “Islamic architecture of Iran” has mentioned that

(…) from 6000 years ago, the material cultures of introverted constructions can be seen. The inside of the house was a place where a woman or a child lived. And it was being built in a way that housewives could work easily and no one could see her. (p.79)

In larger houses, private and public spaces are separated deliberately by sections like entrance, yard, porch, hallway, dooryard (Nejad & Abad, 2016).

Territories from Outside to Inside

The core principle of introversion in Iran can be considered in the construction evolution of the central courtyard. Buildings with courtyards in Iran are about eight thousand years old. (Soflaei et al., 2017; Soleymanpour et al., 2015). As Pirnia (2005) said, “in Iran, they build a garden and a pool in the middle of the house and the rooms and halls wrapped around it like a closed embrace.” (p. 186)

Another principle of introversion is related to facades. There was no window or a hole in the house, or outside the wall. So that it could be seen from the outside, and the exterior was designed with arches, gates and congresses. And only had a gate or headboard that considered opening.

Some features of the material cultures of introverted constructions, the following can be mentioned:

Lack of direct visual connection among the interior spaces (private and semi-private) and outside spaces (public spaces),

Forming the spaces of the house with objects like courtyards and porches. So that the openings lead into these objects.

In Iranian Islamic architecture, not everyone is allowed to disturb the privacy of the family, and the order of entrances to Iranian house is as follows:

Most of the house had entrances, the side platforms in front of the entrances were flat, which provided a suitable space for those who wanted to see the owner but did not need to enter the house,

The connection between the inside and the outside of the house is not as it is today, the visual privacy of the residents of the house was completely secured and not every passer-by could enter the home. Even in the garden house, the yard or garden was large enough that it was impossible to see inside the home,

In the urban size, the alleys path had mazes that have a role of sight breaking and cause private spaces along the private and public route.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 5: Distinction between the exterior and interior space of a home in Birjand

Territories from within

Introversion and Iranian architect’s attraction to the courtyards and pits of gardens, porches and pergolas that surround the naves and create attractive and familiar environments have long been the logic of Iranian architecture. Privacy is one of the concepts and elements that was effective in the design organization of architecture and urban planning, and the architect has used special strategies to reach this need. Spatial order (step-by-step movement from alley or street to the entrance space of the house and then private spaces) as well as the internal and external system operation is a way to provide decent privacy.

In the Iranian house, there are three spaces: public, semipublic (semi-private) and private (confidential territories).

- Entrance: The entrance spaces themselves are part of the sequence of interconnected and related spaces of the whole home. For entering the building, the door and front of the home are both a barrier to entry and a place to greet semi-familiar guests. This space is used as a waiting entrance for newcomers, where the residents of the houe make some usual compliments. Next to the entrance, there are platforms called Pakhoreh, which passers-by sometimes stop for a while to relieve their fatigue under the shadow. Therefore, the location of two platforms on either side of the entrance is an expression of the value of communicating with neighbors and paying attention to citizenship rights. Individualize the door knockers of men and women on the doors proves the principle of secrecy. Muslim architects believe that the doors of houses in neighborhood units should not be opened facing or close to each other.

As shown in Figures 6 & 7, in the traditional houses such as Tabatabai’ Houses, there is no view from the outside of the home to the inside, and the direct visual connection between the interior spaces and the outside space is completely cut off.

- Porch and corridor: Porch or “karbas” is a space that has been designed and built in many types of entrance spaces. This space is often located right after the entrance space and one of its functions is to divide the entrance path into two or more directions. In some public buildings or homes, two or more paths led into the porch, each of which led to a specific space, including the interior of the building, which is the courtyard.

In buildings from which only one way out of the porch, the porch space did not function as a dividing space, but was used as a space for waiting and glorious entrance. Porches have regular geometric shapes with mostly low height and are suitable for the entrance space (Nabavi & Ahmad, 2016).

Dedicated dead-end or porch (semi-public space - semiprivate space) has the following features (Figure 9):

As the doors of the houses open to the space like a platform, porch, or dead end, it creates the feeling of ownership and security.

Residents can come together and make decisions by consulting and contacting each other without any interference in their private space.

Access order avoids crowds and public commuting

Semi-private - semi-public spaces that belong to several families, have led to the visiting and familiarity of residents with each other and, as a result, residents are aware and careful about the area of their common space. Therefore, the porches have both an architectural function and are harmonized with the elegance of social life.

Source: Authors

Figure 7: Toraab home’s Hashti and Masoudieh’s porch for entrance of parivate syntax

Corridor:

The corridor is the simplest part of the entrance space, the most important function of which is to provide communication and access between two places. In some types of buildings, such as houses, baths, and in some cases mosques and schools, the extension and direction of the passage has been changed in the corridors. The corridors lead indirectly to the courtyard, and in this way, designers paid attention to confidentiality.

The corridor is physically narrow and has low width. Of course, the width of the corridors was determined according to the function of the building and the number of users. The average width of the corridors of mosques and large schools is between 2 and 3.5 meters and the width of the corridors of small homes is about one meter on average (Mamani et al., 2017).

Semi-public spaces

Balcony: The balcony can be considered as a space filter and a common part between open and closed spaces. Open or semi-public. In general, the balcony is used as a jointing space in Iranian architecture.

Yard: Housing is important in Islamic architecture due to its direct connection with the private life and family life of the people. A Muslim’s house should be the guardian of his family and should be built in accordance with the religion of Islam. In this regard, the main effect of Islam in the structure of a traditional house is introversion. Burckhardt (2009) describes the courtyard as an aspect of Muslims. He wrote in this case: Muslim homes receive light and air from their inner courtyards, not from the street (Figure 8 & 9).

House spaces

Types of rooms: The most varied and widely used part of the house has been the interior so that the residents of the house do not feel tired and repetitive. The rooms in a traditional house were arranged around the yard according to their importance and use. Summer rooms were usually located on the south side to be less exposed to the sun during summer days, and winter rooms were located in front of the summer rooms and exactly on the side that gets the most sun during the day. Other spaces such as storage, kitchen and stables were located in the second row and behind the rooms (Mamani et al., 2017).

Service space: A backyard was a type of yard that usually had a secondary and service aspect and was designed and built in a part of the house to provide light and ventilation or as an open space for services, and its position and shape were very diverse. Usually, service areas, including the kitchen or bathroom, which should have been built away from the privacy of the house, have access to these backyards, and while providing services, it is responsible for staying away from public view and maintaining confidential territories for the home’s personal affairs.

Discussion

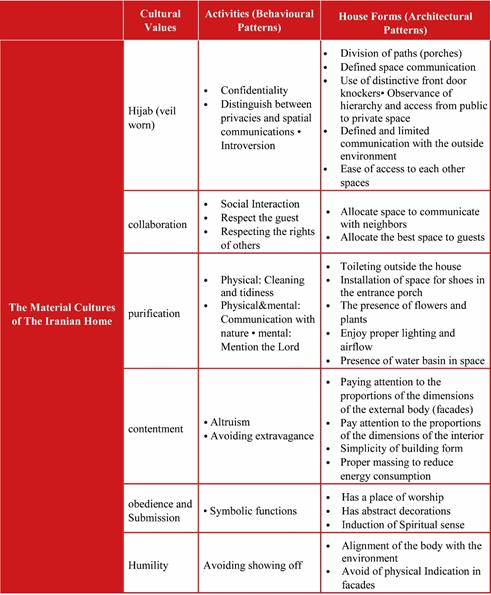

In order to identify the basic concepts of the material cultures of the Iranian home, the relevant codes were discussed in three categories of cultural values, activities (behavioral patterns), house forms (architectural patterns) (Table 2). In each of these three categories, the main criteria and indicators were obtained based on the research literature, field observations, review of plans and interviews, which are shown in Table 3. The main components were identified in the form of six rational and moral values derived from Iranian culture, which are: Hijab (veil worn), collaboration, purification, contentment, obedience and submission, humility.

Conclusions

The home was thus long defined as a fixed and bounded space grounded in activity that occurs in a specific location, but in recent research the home is defined as open, and constructed by movement and communication. Social relations and attached meanings stretch beyond the physical space into the symbolic. Such symbolic meanings show the value and importance of traditions and moral concepts that rooted in the cultural past. At the same time, we need to consider the material home as a result of a complex, fluid, and contested processes both within the home and outside it. Home spaces are seen as shaped by inclusions, exclusions, and power relations. For instance, the material cultures of Iranian homes can convey the gendering concepts where the home is a site of oppression where women are consigned to a life of reproductive and domestic labor with no economic control over its management. Since the home, like other social categories, was masculine because the basis of the home was based on the comfort and wellbeing of men and under the management and authority of the father and the protection of women. Although, at the same time, the material cultures of Iranian homes could be a site of resistance and safety where repressed groups in family (women, girls) or society (minorities) can gain control over certain aspects of their lives.

Also, according to the material cultures of Iranian homes, a space can be considered a home that physically has a social concept and it is considered at least in a relationship between two people and is different from personal territories that have a high value in the modern era in home definitions. The results show that despite the potential of those homes to create personal spaces and territories, there is no definition for that in the material cultures of Iranian homes. Since ancient times, Iranians have shown a tendency towards introverted architecture according to their perception of home and family. The main function of the material cultures of the Iranian house is, above all, to preserve families and collective values. That is why the concepts of home and family have common roots. The material cultures of Iranian homes include Hijab (veil worn), collaboration, purification, contentment, obedience and submission, humility. The most private spaces are interactive spaces such as confidential territories. This kind of territory is not a place that one can be alone. Rather, it is an interactive place for two or more people who feel comfortable with each other semantically, and physically, it creates security for them. Hijab, submission, obedience and humility were emphasized in all the examples. The division of paths and the use of porches and the observance of hierarchy and access from public to private space and decorations clearly convey these concepts. humility and contentment in the material cultures of the Iranian home demonstrated by avoiding showing off in the external facades and using them inside your home. In other words, the Iranian home wants to say that inner beauty and perfection are important and seeks perfectionist architecture.

Changing the values from social values to personal values, and becoming freer the human subject from natural and social limitations causes a challenge to the meaning and power of individual subjectivity and agency. It seems that the material cultures of the Iranian home can be the patterns of designing when they are redefined in a combination of modern and traditional concepts. By valuing privacy and feminine’ principles in combination with collective values taken from moral and rational traditional concepts, while maintaining the peace and security of the inhabitants, the material cultures of Iranian homes can cause personal growth and create a sociable place for households.