INTRODUCTION

Discussions regarding the State’s role have dominated the development literature since the emergence of institutional economics in the 1990s. A consensus is established that a strong State can stimulate economic development (Bardhuan, 2016). However, the absorbing question has been determining what a strong State should be. Stewart (1976) uncovered a snippet of notes from Adam Smith's lectures with sentiments that a State should be at the center of ensuring the triumvirate of peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice (Tohidi, 2019).

Smith's articulation of a tolerable administration of justice hypothesizes that injustice and intolerance obstruct or make social interaction hard or impossible where people do not abstain from injuring each other. This concept has engineered the development of an institution of the RL as a critical factor for inclusive economic development. A strong institution of the RL has the potential to deter or mitigate the grabbing hand of those in power of the use of public resources for personal gain, protection of property and contractual rights, and ensure that hard work is rewarded proportionally (Irwin, 2014; Liu et al. 2018). An effective institution RL system would ensure peaceful coexistence of people irrespective of their differences, hence the smooth operation of economic institutions such as the market. Therefore, the current research seeks to analyze the influence of the institutions of the RL law on inclusive economic development in the SADC region.

Institutions are the humanly devised and enforced rules of the game that shape human interaction (North, 1990). These rules form law and order of the day for society, and define what is permissible in any given circumstance (Leeson, 2017). Through political institutions, such as the RL or the judiciary, the State, through its power, can define and enforce property rights, which provide an indemnity for inclusive development and an improvement in human life. According to Aligica et al. (2019), inclusive economic development can hardly subsist in a society that fails to construct constitutional contracts, that is, law and order. Liu et al. (2018) argued that good governance, which is hinged on the strength of the institutions of the RL, mitigates the grabbing and influences the helping tendency of those in power.

Adam Smith identified three critical roles of the State: 1) providing national defense, 2) ensuring sufficiency of public goods and works, and 3) ensuring that every member of society is safeguarded from injustice or oppression (Irwin, 2014). The State must establish laws but, most importantly, provide a system of courts, police and army to enforce laws, guarantee peace, and uphold national sovereignty (Naidu, 2002).

Likewise, scholars contend that good governance backed by a strong legal framework may ease the socioeconomic strain on emerging countries (Mkandawire, 2007; Banda, 2023b). Africa has long been dominated by neopatrimonialism, which Mkandawire called a ubiquitous moniker for Africa's governments. However, Mkandawire (2015) called for a political system that would give an in-depth analytical content and offer strong predictive value to economic policy and performance, other than Africa's neopatrimonialism. In response, this study considers strengthening the institution of the RL as essential to bring good governance to its epic in African countries.

This institution enables governance to be transparent, fair, judicious, participatory, accountable, well-managed and responsive; and spearheads the efficiency of other development institutions (Grindle, 2010; Banda, 2022a). Without a sound RL, the State may fail in its essential role of correcting market failures arising from unregulated markets (Hammer, 2000). Therefore, the State should support the judicial system by increasing infrastructure, law practitioners, and financing law enforcement agencies like the police and the army (Ellet, 2014).

This study matters in the context of African Regional Economic Communities’ (RECs) relations, especially with SADC leaders, policymakers and researchers, because it provides insights into the significance of the legal framework on inclusive economic development. The most crucial sustainable development goal (SDG) is number 16, that is, "peace, justice and strong institutions", and this emphasizes principles of the RL. This objective supports the creation of peaceful, inclusive communities that foster sustainable development, ensures that everyone has access to justice, and establishes inclusive institutions at all levels of government.

The institution of the RL is believed by the United Nations (UN), its agencies, and members that the institution's success has a multiplier effect on achieving all other SDGs (IDLO, 2020). SDG 16 is a critical driver of achieving all national development plans, because an increase in the accessibility of justice and the RL increases the ability of people to settle disputes, claim one’s rights, and see and seek remedies (Laberge, 2019).

For this reason, the African Union (2015) has integrated SDG 16 into the African Agenda 2030 in aspiration 3, goal 11. The goal seeks a complete renovation of the institutions of the RL, governance and democracy in all African countries. ). Similarly, RECs such as SADC and individual countries have included the agenda of strengthening the RL institutions in their development plans. For instance, pillar number 5 of SADC's Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP) 2020-2030 blueprint emphasizes strengthening peace, security and governance. Aspiration 2 of pillar 5 strictly challenges SADC member states to boost political unity, promote territorial democracy and governance, and prioritize human rights and security principles by making the supremacy of the RL a top priority (SADC, 2020). In addition, SADC recognizes that industrialization and market integration goals pivot on peace, resiliency, and political stability (SADC, 2020). These premises will hardly be attained if the region's RL performance remains unreformed, weak and unempowered.

Furthermore, this study is novel, since matching literature is yet to be directed to the SADC region as a unique economic bloc that cherishes objectives beyond trade to strong political relations among its members. Besides, existing literature focused primarily on the nexus between governance and economic growth (Ndulu and O’Connel, 1999; Dollar and Kraay, 2002; Murtaza and Farid, 2016; Liu et al., 2018; Adzima and Baita, 2019: Noha and I-Ming, 2016; Samarasinghe, 2018; Olson et al., 2000; Kurtz and Schrank 2007; Fayisa and Nsiya, 2013; Setayesh and Daryaei, 2017; Adzima and Baita, 2019; Ekpo, 2020). It is, thus, not unfathomable that the results are highly mixed due to the multifaceted nature of measuring economic growth.

For example, Adzima and Baita (2019) observed that legal capacity depicted the positive a priori influence on national output in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nevertheless, Ekpo (2020) found that good governance does not influence an increase in national output in the same study area. Therefore, this study seeks to divert attention from economic growth-related indicators to inclusive economic development beyond economic growth. Instead, we adopt the Human Development Index (HDI) because the indicator extends beyond output to capture some well-being aspects, such as education and health.

Literature review

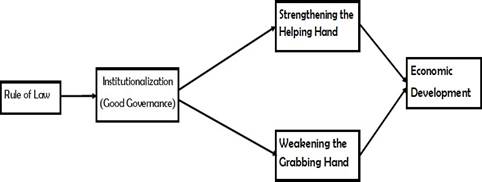

Conceptual framework

This study modifies a conceptual framework from Liu et al. (2018) to its own needs. Such conceptual framework suggests that inclusive economic development is affected by the RL institution, which ensures that political and economic institutions are effective (strengthening the helping hand) and reduce inefficiency and ineffectiveness (weakening the grabbing hand) in these institutions and those in power. Illustration 1 below shows the conceptual framework.

Theoretical framework

Amartya Sen’s capability approach

Unlike governance-growth nexus studies, which mainly adopt the Solow growth model, this study adopts the capabilities approach, which is a theoretical framework that depicts two hypotheses: the first one states that the primary importance of institutions is to attain well-being. The second hypothesis is that the comprehensiveness of well-being should dwell on what people can do (capabilities) and what they have done or are doing (functionings). It is contended by Sen that the ability of people in a society to turn means or resources and public goods into well-being is a function of three mutually exclusive conversion factors: personal conversion factors, social conversion factors, and environmental conversion factors (Fredian, 2010; Robeyns & Byskov, 2021).

This manuscript considers the institution of the RL as a critical social conversion factor that inscribes governance (WJP 2021). In fact, according to Sen (1993), as cited in Walker and Unterhalte (2007), all the instrumental freedom outlined ‒political freedom, transparency guarantees, social opportunities and protective security‒ depicts the elements of good governance. These freedoms, also referred to as "conversion factors", tend to enrich people with urgency and empowerment to achieve well-being (Fredian, 2010; Banda, 2022a).

Acemoglu and Robinson's theory of institutions

In addition to the capabilities approach, the paper incorporates the theory of institutions by Acemoglu and Robinson. This theory is adopted because it clarifies the right institutions needed for inclusive wealth for a nation. Like their predecessors (Deepak Lal and Adam Smith), Acemoglu and Robinson outline the causes of wealth and poverty in economies such as laissez-faire, democracy, and the RL institutions. However, they introduced new ideas in the form of two antagonistic archetypes: extractive institutions and inclusive institutions. The latter, especially the RL institution, enables citizens to participate in decision-making processes (Dzionek-Kozłowska & Matera 2021).

Also, Acemoglu and Robison argued that the wealth of economies differs primarily due to differences in political and economic institutions, since this rule governing markets in an economy and the incentives that stimulate hard work among people (Acemoglu & Robisnson, 2012). The RL is one political institution that, if fair, transparent and supreme, can enhance political pluralism through voice and accountability, control of corruption, checks, and balances. In other words, political pluralism has the potential to strengthen the helping hand and weaken the grabbing hand of those in power (Lie et al., 2018). Therefore, engaging the masses in decision-making will facilitate an efficient allocation of resources, thereby improving inclusive economic development due to increased pro-poor policies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data

We used annual data for all 16 countries from the SADC from 1996 to 2019. Data on the dependent variable (HDI) was collected from the United Nations Development Program database (UNDP, 2020). On the other hand, data for the primary independent variable, the RL index, was obtained from the World Bank (2020). Finally, data for Official Development Assistance (ODA) and aid was obtained from the World Development Indicators [WDI] (World Bank, 2021).

Econometric specification

Based on previous empirical studies (Liu et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2013; Huynh & Jacho-Chavez 2009), we expect a nonlinear relationship depicting diminishing or increasing returns between economic development and the RL. However, this verdict will be drawn from the scatter plot in section 4. Initially, we systemically specify the linear econometric model as follows:

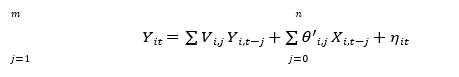

Where HDI, RL and ODA are considered. On the other note, 𝛽0 is the intercept; 𝛽1 and 𝛽2, are the coefficients to be estimated; μ depicts the country effect; λ represents the effect of time; ε is the random disturbance representation; and i and t denote countries and time period respectively. In reference to Pesaran et al. (1999), we consider the panel ARDL (m, n) model, as specified in the following equation:

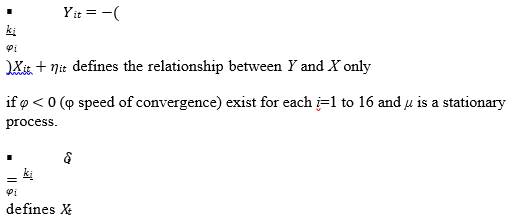

Subtracting the lagged regressand (𝑌𝑖𝑡) from both sides of equation 2 allows the dynamic heterogeneity in panel regression to be added into an error correction model using an ARDL (m, n), as shown below:

Where y denotes the dependent variable (HDI), X represents a list of independent variables including RL and ODA. On the other hand, there are some parameters, as explained below:

θ and V respectively denote the short-run coefficients of lagged independent and dependent variables.

φ and k denote the speed of adjustment to the long-run equilibrium and the long-run coefficients.

Η denotes the country-specific intercept.

Similarly, the subscript i and t denote cross-sections and time, respectively. Likewise, the term 𝑌𝑖,𝑡−1 − 𝑘′ 𝑖𝑋𝑖,𝑡−1 in equation 3 denotes the long-run relationship between Y and X (ECT); and, according to Pesaran et al. (1999), two assumptions justify this long-run relationship:

across all countries, as 𝛿𝑖 = 𝛿 (assumption of no long-run heterogeneity).

In the same way, equation 2 provides the intuition into k-convergence because φ is interpreted as the speed of adjustment towards the long-run equilibrium state. Equation 3 will be estimated by either of the panel ARDL estimators, namely, the mean group (MG) advanced by Pesaran and Smith (1995); the PMG, established by Pesaran et al. (1999); and the DFE estimator. The selection of the estimator will be decided by the Hausman model test, which identifies the best and most efficient estimator suitable for the data under study.

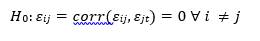

Cross-sectional dependence

We adopt two tests: the Breusch Pagan (1980) lagrangian multiplier (LM) test, and the Pesaran (2004) scaled LM test to control for CD. The test designates the interrelatedness among the error terms of each group in a study. Otherwise, flouting the test for cross-sectional dependency can lead to inefficient estimators and worthless test statistics (Iheomu & Nmwachukwu, 2020). The general null hypothesis of this test is given as:

In this sense, the test's outcome is significant because it allows researchers to achieve efficiency gains, which would not be the case when running separate ordinary-squares regressions for each cross-section. Thus, it is statistically faulty to pool a sample of cross sections that is not heterogenous in slope parameters (De Hoyos &Sarafidis, 2006).

Panel data diagnostic tests

Co-integration relationship between X and Y will be validated by a negative and statistically significant coefficient of the ECT (𝑌𝑖,𝑡−1 −

𝑘′ 𝑖𝑋𝑖,𝑡−1) in equation 3. In terms of the panel unit root test, the study applied the Pesaran (2007) cross‐sectional augmented Dickey-Fuller (CADF) test, which takes into account cross-sectional dependence. This test yield optimum precision while being cloistered from the CD issue, which is common with panel data (Iorember et al., 2022).

We used the Ramsey’s regression specification error tests (RESET) to certify the correctness of the specified model for reliability of empirical results. According to Gujarati (2004), the Ramsey RESET is the only general test for misspecification and barely needs other supporting specification models. For appropriate model selection, the study used Bayesian information criteria (BIC) to test for optimal number of lags to be included in the regression model. In addition, the matrix information test was used to test model specification, heteroscedasticity and normality of residual terms. On the other hand, the Pearson correlation matrix analysis and the variance inflation factor (VIF) were incorporated to check the incidence of multicollinearity in the model.

Empirical results and discussion

Descriptive statistics

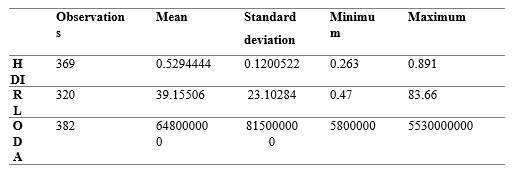

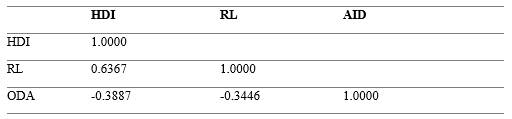

Table 2 shows summary statistics, which prove that it is evident that data points for human development and the RL are clustered around the mean values of 0.53 and 39.16, respectively; and Table 3 presents the results of the Pearson correlation matrix, which shows a strong positive relationship between the performance of the RL and the inclusive economic development. The trend analysis in Illustration A1 further supports the positive relationship between the two variables of interest. Therefore, it is evident that in the year ranges 2001-2003, 2006-2007 and 2012-2019, the two variables are moving in the same direction.

In addition, illustrations A2, A3 and A4 show the trends for SADC countries for each variable. For example, Illustration A2 reveals that Mauritius and Seychelles are top while Mozambique has the least inclusive economic development in the SADC region. On the other hand, Illustration A3 shows that Mauritius, seconded by Botswana, tops the region in terms of performance of the RL institution.

Pre-estimation test results

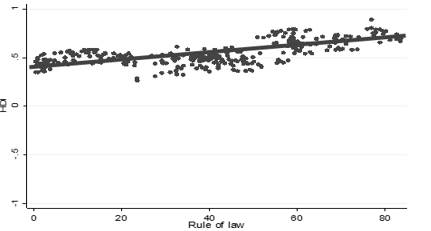

Illustration 2 presents the Cartesian coordinates on a scatter plot, which shows that the inclusive economic development and the RL are linearly related, since there is less evidence for diminishing or increasing returns. This linear relationship between the performance of institutions of the RL and economic development implies that the study’s primary explanatory variable (RL) enters the econometric model in its pure form. The linear relationship confirms the model specified in equation 1 in section 3.

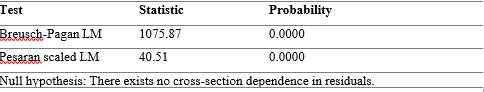

Tables 4 and 5 present the results of cross-section dependence and panel unit root tests. The Breusch-Pagan lagrange multiplier (LM) test and the Pesaran scale LM test are statistically significant at conventional levels, such that we reject the null hypothesis of no cross-sectional dependence, and we conclude that the errors across the countries in the model are correlated with each other.

Table 4 Cross-section dependence test results

Note: standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Consequently, we incorporate tests and estimation procedures that accommodate cross-sectional dependence to avoid pooling a cross section that is homogenous, which reduces efficiency gains. For this reason, we adopt the Pesaran (2007) CADF, whose results reveal the absence of unit root after taking the first difference for all series. The order of integration of series makes panel ARDL a more appropriate model, since it is only applicable for series integrated of order 0, I(0), or order 1, I(1), or both and not otherwise.

Table 5 Pesaran’s (2007) CADF panel unit root test results

Note: standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

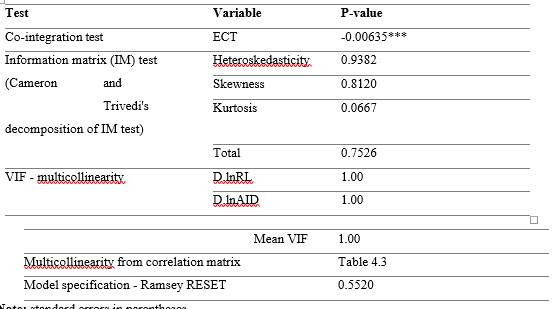

Therefore, we present the panel ARDL diagnostic test in Table 6. The results of the Ramsey RESET show that the model is well specified. Similarly, the p-values of the matrix information test lead us to fail to reject the null hypothesis of no model misspecification, no heteroscedasticity and no normality among residual values. In addition, the mean VIF is far below 10; hence, there is no multicollinearity. The result concurs with the Pearson correlation matrix in Table 3, when no pair of variables are correlated above

0.8. Finally, the ECT is desirably negative and statistically significant, thereby confirming a co-integration among the variables of the study.

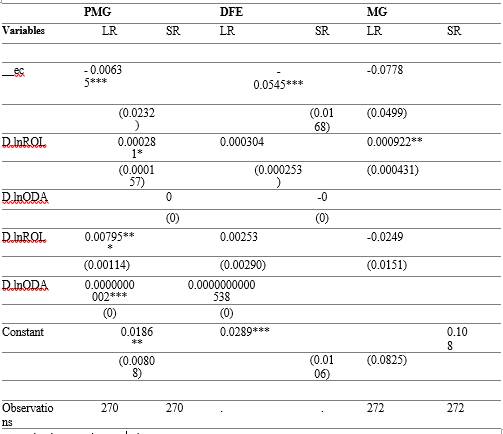

IV.3. Long-run and short-run estimation results

Table 7 presents the long-run and short-run outcomes for all panel ARDL estimators regarding the influence of the institutions of the RL and ODA on inclusive economic development in SADC member countries. However, the discussion will be based on the PMG estimator, which is favored over the MG and DFE using the Hausman model test. The lag list ARDL (100) was guided by the BIC.

Table 7 Panel ARDL long-run and short-run estimation results

Note: standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

The PMG estimation results indicate a strong co-integration relationship among the study variables because the error correction term is desirably negative and statistically significant at conventional levels. Therefore, we have enough evidence for the speed of adjustment or convergence to the long-run equilibrium state after encountering various shocks. The estimated coefficients of long-run and short-run model for the RL are statistically significant at a 1 % level.

Therefore, we are 99 % confident that an improvement in the performance of the RL institutions positively influence inclusive economic development in the SADC region. The long-run coefficient of the RL reveals that a one-unit improvement in the performance of the RL institutions results in a 0.0079 unit increase in inclusive economic development in the SADC region, at ceteris paribus. At the same time, the short-run coefficient of the rule of law indicates that a one-unit improvement in the performance of the rule of law institutions results in a 0.00028 unit increase in inclusive economic development in the SADC region at ceteris paribus.

These findings are in line with the theoretical expectation that, as the institutions of RL evolve, inclusive economic development improves. For example, a strong institution of the RL will mitigate the grabbing hand and enhance the helping hand of those in power. Furthermore, we argue that a strong institution of the RL is critical to citizens' participation in the democratic process -national, regional and local decision-making processes- through an enhancement in the right to speech. Political leaders can distribute resources more effectively among alternative users as a result. In other words, there will be a fair distribution of the nation's output, access to health and educational facilities, and effective management of both public and private sector investments and service delivery.

Likewise, a reasonable standard of living and market prospects for residents will certainly improve as a result of this phenomena, leading to inclusive economic development. Similarly, the estimated long-run coefficient for ODA depicts a positive relationship with inclusive economic development and is valid with 99 % assurance. That is, a one-unit increase in the inward flow of aid in the SADC region will lead to a 0.00000000002- unit improvement in inclusive economic development in the region in the long run, at ceteris paribus.

On the other hand, the PMG estimator imposes restrictions in the long-run results while allowing for heterogeneity in its short-run estimates. This study provides heterogeneity in short-run dynamic estimates for SADC because of differing government effectiveness and vulnerability to political shocks, fiscal policies, constitutional supremacy, legal manpower, among others.

Facing this, Table A1 presents the generic heterogeneity PMG short-run estimates. The institution of the RL maintains a positive and statistically significant influence on inclusive economic development in Lesotho, but a negative and statistically significant relationship in Malawi. Moreover, the negative impact of the institutions of the RL on inclusive economic development in Malawi sparks evidence of neopatrimonialism ‒scenario for patron-client networks, corruption and rent-seeking behaviors‒ (Fransisco, 2010; Bach and Gazibo, 2011).

Discussion

The positive influence of the institution of the RL on inclusive economic development in the SADC region is consistent with the findings of Adzima & Baita (2019), Murtaza & Farid (2016), and Afolabi (2019). These studies also observed that the institutions of the RL positively influence the economic performance (measured by GDP) in Sub-Saharan Africa, Pakistan, and Western Africa, respectively. Zouhair (2019) also observed that the rule of law institutions positively influences economic development in SADC and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). It is not surprising that Earl & Scott (2009) argued that consolidated democratic regimes with solid legal framework enjoy higher quality governance, enhanced magnitude of economic performance, and easily adhere to pro-poor policies.

Moreover, Irwin (2014) stressed that it is difficult or impossible to motivate the accumulation of wealth where plundering, pillaging and perpetual wars form the moment of each day. That is, when people find themselves under the threat of robbery, they will have no motive to be industrious. How can a nation develop; how can people eat, teach, study, work and raise families without peace? These are just a few issues that insecurity brings up. In addition, how can a nation achieve peace without justice, respect for human rights, and a legal system of government? (UNDP, 2016). These questions call for a strong and effective written national encyclopedia of laws to set a prism of principles of national policy and guide State priorities to achieve sound economic performance (Gloppen & Kanyongolo, 2007).

It is not uncommon that the short-run heterogeneity estimates revealed a negative influence of the institution of the RL on inclusive economic development in Malawi. For example, Zouhair (2019) observed that the institution of the RL leads to a deterioration of economic development in the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the intergovernmental authority for development (IGAD) countries. Using income per capita as a measure of economic development, Ekpo (2020) also observed that the institution of the RL negatively affects the economic performance in SADC countries.

Such conclusions are trans-historically inscribed into the ancient concept of neopatrimonialism. Indeed, other scholars contend that this system of neopatrimonialism is not always detrimental to development as advanced by the donor orthodox (Cammack & Kelsall, 2011). The argument here is that strong institutions of the RL may demotivate those in power from being effective and efficient, since they are unlikely to enrich their own pockets from the success of public investment projects they initiate.

Similarly, Beliamounie et al. (2009) noted that corruption, a component of neopatrimonialism, leads to an increase in public sector investments, which may improve the economic development of a nation more than the private sector. However, Cammack et al. (2007) stressed that it is difficult to construct the novel institution of governance, where existing patron-client relationships are deeply ingrained and favor specific influential factions of a society.

Lastly, the long-run panel estimate reveals that ODA positively influences inclusive economic development for SADC member states. Also, Minoie & Reddy (2010) noted that a 1 % increase in aid from Nordic countries leads to a 1.5 % point increase in economic performance in developing countries. Similarly, Sebastian et al. (2016) found that aid significantly influences economic development in countries where it is the dominant source of fiscal and development funding.

However, Matola (2014) observed that, without a strong government, aid does not enhance the betterment of human life in Southern African countries. That is the case in this study for Malawi and Zimbabwe, where ODA is found to negatively influence inclusive economic development in the short-run. Without government effectiveness, funds from aid are grabbed mainly by those in power without serving planned investment projects in low-income countries (Zardoub, 2020).

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

This study examines the impact of the performance of the institutions of the RL on inclusive economic development in the SADC region. We employed the panel ARDL model to analyze the short-run and the long-run co-integration relationship between the variables for data from 1996 to 2019. The Hausman test results favored the PMG estimator over the MG and DFE estimators of the panel ARDL model, so the ECT revealed a co-integration relationship between the study's variables. In the restricted panel, a strong legal framework is found to be positive and statistically significant to the attainment of inclusive economic development in the region. That means that the anchorage of the institutions of the RL is vital if economic integration is to be achieved.

This study, therefore, offers policy insights for policymakers in SADC, which can be inferred to other African RECs to assist their member states in strengthening the administrations of justice to promote peaceful coexistence among people. Strong institutions of the RL are critical to African RECs because economic integration gauges countries to negotiate to bide laws to govern the operations of trade, which extend to all members involved and their sub-parts. Therefore, we recommend that these regional trade laws are integrated into each member's national laws, and common courts should be set to adjudicate disagreements over compliance by individual citizens or one country against another. The supremacy for such adjudications and sanctions promotes the peaceful coexistence among traders of different nations and guarantees economic integration and development.

Finally, we also suggest the need for a concerted effort to implement legal initiatives to address and redress the challenges faced by the SADC region. A suggestion is made to increase commitment to constitutionalism in SADC member countries, provide a framework to track the adherence to transnational trade laws and policies, and promote bidirectional or multidirectional collaborations among national and regional institutions. Furthermore, the SADC region should incentivize increased participation among legal stakeholders.

For future research, we recommend incorporating the RL index developed annually since 2013 by the World Justice Project (WJP). The index provides a more comprehensive methodology, because it combines all elements of WGI and adds criminal justice and civil rights. However, using this index will require a large panel to gain more data observations, which could have otherwise not been possible in this SADC restricted study.