INTRODUCTION

Parkinsonism is a well-recognized sequelae of diverse toxic insults to the brain which include - but are not limited to - carbon monoxide poisoning, cyanide intoxication, heroin overdose, and alcohol toxicity (1)(2)(3)(4). These conditions have been associated with selective (or almost selective) necrosis of the globus pallidus, which most often result in a syndrome called pallidal-Parkinsonism that may be followed by dystonic manifestations in some cases (5). Here, we report a patient who developed pallidal Parkinsonism after a heavy binge drinking episode in which the pathogenetic mechanism associated with its appearance was likely due to complications related to alcohol intake and not to a hypoxic-ischemic insult to the brain.

CASE REPORT

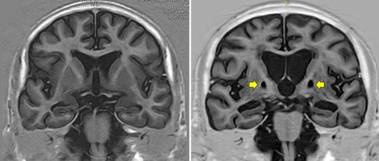

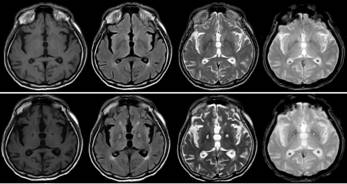

A 77-year-old man with history of arterial hypertension and heavy alcohol intake was first evaluated after his enrollment in the Atahualpa Project Cohort (6), on June 2014 (when he was aged 70 years). At that time, he received a neurological examination and a brain MRI for research purposes (Figure 1, upper row) which were normal. During these years, he has been actively enrolled in the cohort and received multiple clinical examinations and complementary tests, which have been within normal limits with the exception of an abnormal ankle-brachial index determinations signaling peripheral artery disease. Over the past two years, he received several finger-prink blood tests for detection of SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM antibodies, which were negative in all determinations. According to proxies’ comments, the patient had experienced several episodes of loss of consciousness after binge-drinking and has been found lying on the village’s streets but had always responded to verbal commands. Six months ago, after one heavy binge-drinking episode, in which the patient drank several bottles of cane liqueur (50% alcohol) during an entire week, he was found unconsciousness at the street and did not respond to verbal commands or painful stimuli for a couple of hours until he spontaneously woke up. During the time that the patient did not respond to stimuli he breathed spontaneously and the skin was pale but not cyanotic. Over the following weeks, his neurological conditions changed. He progressively developed slurry speech, action tremor in both upper limbs, generalized bradykinesia, and the gait became unsteady and shuffling. A new MRI revealed bilateral symmetric necrosis of the globus pallidus as well as severe cortical and hippocampal atrophy (Figure 1, lower row; and Figure 2). The patient declined treatment for his condition. (Figure 1)(Figure 2)

Figure 1 MRI of the patient before the event disclosing no major abnormalities (upper row). Six months after the event (lower row), there is evidence of bilateral and symmetrical necrosis of the globus pallidus, which is noticed in all MRI sequences in the axial plane, including from left to right: T1-weighted, FLAIR, T2-weighted, and Gradient-echo.

COMMENT

Bilateral necrosis of the globus pallidus has been reported to contribute to several motor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease. However, the paucity of individuals with isolated lesions of the globus pallidus made it difficult to ascertain the role of these nuclei in different motor functions (7).

In the present report, the patient had an episode of unresponsive unconsciousness after massive alcohol intake, which was not associated with cyanosis or the need of respiratory support. Therefore, it is likely that such an episode was associated with alcohol intoxication-related respiratory acidosis as was the case reported by Kuoppamaki et al (4). Indeed, both (the present case and that already mentioned) share important features such as the precipitating event, the spontaneous initial recovery, and the development of pallidal Parkinsonism some months after the acute event. Moreover, respiratory acidosis in the setting of acute alcohol intoxication has been reported elsewhere (8). A limitation of the present case report is that arterial gasometry was not determined during the acute phase of the intoxication, but other pathogenetic mechanisms appear less plausible. Likewise, the ingestion of adulterated alcohol could not be totally ruled out, but the absence of visual complains makes unlike that methanol was responsible for the patient’s complaints (9). In addition, we could recovered the bottles that the individuals had been drinking before the episode and that particular liquor had been properly registered (sanitary permission) in the Ecuadorian Minister of Health.

In summary, this case provides proof-of-concept of pallidal Parkinsonism as a delayed and severe consequence of binge drinking. Toxic or anoxic-ischemic injury of the globus pallidus are the two mechanisms by which the aforementioned condition may cause pallidal Parkinsonism and must be kept in mind at the time of differential diagnosis.