INTRODUCTION

In contemporary society, competition between people and organizations has become an inseparable feature of their performance. Everyone wants the best individual to employ in their organization, the most prepared, the most competent; in fact, the meaning of competence is associated both with being adequate or sufficient for something, and with being prepared to compete with others. At the organizational level, competition acquires its own nuance that goes beyond the ability to successfully perform its functions, and focuses on the struggle between institutions or companies for market dominance.

In both cases (people and organizations) the measurement of competence requires the establishment of evaluative patterns that allow defining positions or scales, which ultimately lead to placing individuals or entities in an order of merit. In the academic field, examples abound: the ranking of universities, the evaluation of teachers, the indexing of scientific journals, the academic index of students, and others. This is ultimately intended to determine the quality of the system and its products, based on their competence.

In higher education, quality assessment emerged as a diagnostic instrument, but it has become a mechanism to manage educational systems (Vera & González-Ledesma, 2018). Two approaches to educational quality have coexisted in the last twenty years; the first is given by the purely competitive intention of positioning processes and universities in international rankings, which leads to the concern that not all institutions that operate in different contexts can be comparable (Montoya & Escallón, 2013). The second approach is represented by a social-humanist tendency, in which emphasis is placed on "

” (Stubrin et al., 2007, p. 8).the commitments of institutions with the social meaning of knowledge and training, the ethical and moral values of collective well-being, the democratization of access and permanence, social justice and sustainable development

Under these premises, is it possible to reconcile both interests without conflicting? The objective of this article is to review the recent information backing the competitive and social-humanist approaches to quality in postgraduate studies, and on this basis support what should be the meeting point between both approaches in Latin American universities.

METHODOLOGY

This is a review article, in which current information on the criteria that prevail in determining quality in postgraduate studies was analyzed. 37 articles published mainly in the Scopus and Scielo databases, and others such as Crossref, Dialnet and ROAD, were reviewed. For collecting the information, keywords linked to the revised themes were employed, like quality management, quality standards, accreditation, pertinence, sustainable training and post graduate studies. Mainly, articles published in the last 5-10 years were selected.

Also, the positioning of universities in the three rankings considered the most relevant: QS World University Rankings (QS-WUR), Times Higher Education (THE) and Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) (IDP Connect Limited, 2022) was consulted. Documentary analysis was used to identify elements that coincided with the competitive and humanist-social approaches in the reviewed documents. From the review and analysis of the points of view expressed in the consulted documents, reflections on quality management in postgraduate studies were formulated from the Latin American perspective.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

THE COMPETITIVE APPROACH IN THE QUALITY MANAGEMENT OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES

The global tendency to compete mutually between organizations, including universities, has led to the establishment of indicators with the aim of defining which are the best. The positioning criteria of universities are varied, but three classifications are considered the most important worldwide:

QS World University Rankings (QS-WUR): Founded in 1990 in the United Kingdom, it considers the academic reputation of teachers (30%), the reputation of employers (20%), the student-teacher ratio (10%), the number of citations for faculty (5%), the articles published by each faculty (10%), the number of PhDs in the staff (5%), the web impact (5%), the number of international students (2.5%), the number of foreign teachers (2.5%) and the international research networks in which the university participates (10%).

According to the data published in the QS-WUR for 2023, ten Latin American universities are among the top 400, out of the 1,200 universities contained in the ranking (Table 1).

Table 1: The 10 best ranked Latin American universities in 2023 according to QS World University Ranking

Source: OS World University Rankings (2023)

In this ranking, the top three places were taken by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, the University of Cambridge, UK, and Stanford University, USA, showing just how far behind they are the best Latin American universities in terms of the competitiveness criteria used by this ranking.

Times Higher Education (THE): This weekly magazine, founded in 1971 in the United Kingdom, has published an annual ranking of universities since 2004. Until 2009 it was associated with QS World University Rankings, and since that year it has operated independently.

This organization uses roughly similar variables to the QS-WUR, but in locating the best ones, first considers the number of full-time students, the number of students per teacher, the number of international students, and the female/male ratio in the student body. Apparently due to the preponderance of these variables, the Latin American universities in this ranking appear in much lower positions than those they occupy in the QS World University Rankings. The top ten Latin American universities ranked in THE in 2022 are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: The 10 best ranked Latin American universities in 2022 according to Times Higher Education

Source: Times Higher Education (2022)

In THE, the best ranked universities are, in that order, the University of Oxford (UK), Harvard University (USA) and the University of Cambridge (UK).

Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) (IDP Connect Limited, 2022): Since 2003, this classification has been made by a group of specialists from the Jiao Tong University in Shanghai, China. Their ordering criteria are based on the quality of education and faculties (for which they consider the Nobel prizes and Fields Medal obtained), research (articles published in Science, Nature, and indexed in SCI), and academic performance per capita of universities.

This ranking, even more selective, only includes Brazilian and Chilean universities (Table 3).

Table 3: The 10 best ranked Latin American universities in 2022 according to Academic Ranking of World Universities

Source: IDP Connect Limited (2022)

In ARWU, the top three places are held by three American universities: Harvard University, Stanford University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

As can be seen from the data shown, there is a high coincidence between the English and American universities that occupy the first places in the world. As for Latin American universities, although some appear in the three rankings, this level of coincidence is not so high; even, as pointed by Páez et al. (2021) important variations from one year to the next may occur.

The tendency to locate universities in certain positions has led students to seek access to institutions based on the quality of faculty services, classrooms, laboratories and libraries, lodging and transportation, and even to the development of specific studies to determine the quality of these services (Mapén et al., 2020; Agboola et al., 2019; El Alfy and Abukari, 2019; Afrin and Rahman, 2020; Al-Mekhlafi, 2020; El-Hadidi, 2022).

THE HUMANIST-SOCIAL APPROACH IN THE QUALITY MANAGEMENT OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES

The pertinence of universities is a concept that has been interpreted differently by various authors, who in many cases tend to associate pertinence with the ability to respond to the demands of the economy and production. However, authors such as Estupiñán et al. (2016) and Álvarez et al. (2018) emphasize the relationship of the university with its social environment, understood as the way in which the higher education institution is linked with all the actors of society, in an inclusive manner and favorably influencing the harmonious development of the individual and of the people in general, showing responsibility with the environment and the future of the new generations.

This commitment of the university to society has been called social pertinence (Sosa et al., 2016; Álvarez et al., 2018) and is associated with university social responsibility, which implies a commitment to society from the study plans themselves (Olarte-Mejía and Ríos-Osorio, 2015). For Roque et al. (2016), postgraduate clients are not only the students and the institutions that send them to acquire a fourth level of training, but also society as the scene of the impact of these professionals. Based on these concepts, Luzuriaga et al. (2019) consider that in the procedure to evaluate the quality of the postgraduate course at the Autonomous Regional University of the Andes (UNIANDES), the social impact and the transfer of knowledge should have an important weight.

Acevedo-Duque et al. (2022) point out that, in a world threatened by climate change, the waste of resources, famines and armed conflicts, it should be the responsibility of universities, and in particular of postgraduate studies, to prepare professionals who can face these challenges. For this, they consider that postgraduate programs should establish lines of training depending on the region in which they are taught, and in which the political, economic, social and cultural actors of these fields must be involved. On this basis, several Latin American universities that offer postgraduate programs are redesigning them, incorporating an environmental and transdisciplinary vision, with a solid ethical project and without ruling out technological advances (Acevedo-Duque et al., 2023).

This trend is based on the concept of socio-formation, which implies that students solve real problems in specific areas of action in society, based on their own experiences (Tobón et al., 2015). To fulfill this purpose, the training of professors who will teach the postgraduate courses is of paramount importance. Aliaga-Pacora & Luna-Nemecio (2020) consider that the investigative skills of the students should be oriented towards their performance in the knowledge society, to take advantage of this knowledge in solving context problems. It is not only about acquiring scientific-technical knowledge, but about using it, based on a sustainability thought for the future of humanity (Nikolaiev, 2016).

Public universities should constitute per se a space where these transforming thoughts are generated, and yet they often limit themselves to teaching what is done in developed countries; in this way, the teaching and research plans and policies are much more similar to those of developed countries than to those of our context, despite the differences in their realities, budgets and environments (Pineda-López et al., 2019). This is one of the factors by which there is a divorce between what students and teachers consider as environmental education and what actually appears in the curricula (Amador et al., 2015), and a barrier to solving real problems by postgraduates is created.

THE COMPETITIVE APPROACH vs. THE HUMANIST-SOCIAL APPROACH

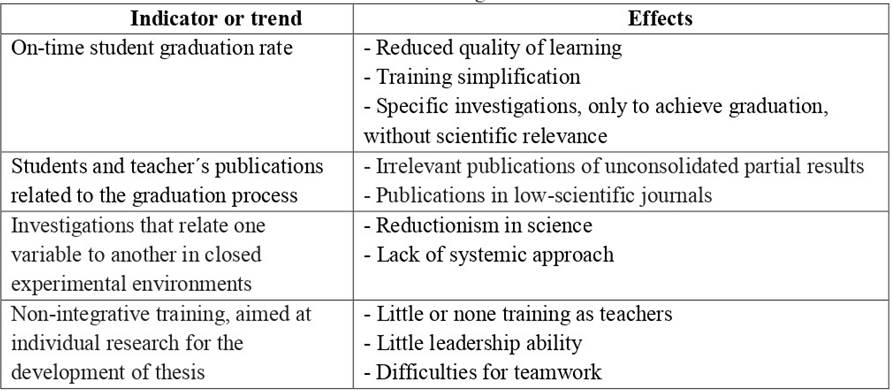

Abreu-Hernández and De la Cruz-Flores (2015) point out that the postgraduate studies have tended to train cadres capable of being employed by transnationals and not to the development of endogenous knowledge. This goal, based on Fordism and Taylorism of the first decades of the 20th century, has led to the standardization of the quality of postgraduate processes based on variables that are easily measurable in numbers, such as the number of PhDs in the faculty, the articles published in certain types of magazines, the prizes obtained, and others. In the evaluation of the quality of the current postgraduate studies, some indicators and trends carry on counterproductive effects in the medium and long term, which are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Trends and indicators of postgraduate quality and counterproductive effects in the medium and long term

Source: Own elaboration based on Abreu-Hernández and De la Cruz-Flores (2015)

Requirements such as the need to graduate within a certain period and to publish an article linked to the graduation process lead to research being carried out solely aimed at obtaining results that allow writing a thesis based on them. These investigations, although they allow the graduation of the student, do not contain relevant results, and are often published in journals of little scientific level. An important factor that has contributed to this is the global trend that has been manifested since the beginning of the millennium towards reducing the duration of master's programs to one year (Cruz, 2014).

This decrease in graduation time, however, has not been reflected to the same extent in doctoral programs, which generally last 3-4 years. Instead, new ways of obtaining a doctorate have appeared, such as the one based on the publication of a variable number of articles on a scientific topic, which has been adopted by many universities, with its advantages and disadvantages over traditional theses (Pérez-Piñar et al., 2017).

The propensity to carry out research in closed environments, with experimental designs that correlate variables outside the real context in which the phenomena occur, constitutes a particularly important danger in postgraduate training. In this way, the paradox can arise that a brilliant student, author of a publication in a journal with a high impact factor, finds it difficult to develop later in contexts that demand a holistic vision, integrating variables that were excluded from the design of his research to graduate. Likewise, the vertical formation of the students in research leaves gaps in their training as teachers and leaders, and diminishes their abilities to make and integrate into collaborative teams, skills that all postgraduates should have for their insertion in society. This is another inconsistency since, as a rule, universities and many research centers require a postgraduate degree to access certain teaching and scientific positions, which puts universities in the role of producer-consumer of postgraduates (Araujo and Walker, 2020). Contrast this situation with what is considered a benchmark in the European model regarding the inclusive training of postgraduates (Walker et al., 2008, cited by Cruz, 2014) as teachers, researchers and leaders with ethical and social responsibility.

Numerous universities maintain this style of work, pressured by postgraduate quality assessment systems; although the will to avoid the commodification of higher education is officially declared, in practice the quality indicators that are required force them to be included in the competitive model, because the weight of indicators of this type is greater than that of those measuring the insertion in society and the link with social problems (Sánchez et al., 2018).

This situation can acquire more complex nuances when trying to obtain international accreditation. For example, in the quality management model designed by Ferreiro et al. (2020) to direct the postgraduate processes of the Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico, towards international accreditation, the variables that are taken into account are typical of the competitive approach (academic staff, students, study plan, assessment and continuous improvement, infrastructure, equipment and institutional support) without considering, at least explicitly, indicators linked to the socio-cultural role of the university in its environment.

The management models of university processes, such as those proposed by Bustos et al. (2016) and Véliz et al. (2020) inevitably lead to priority compliance with this type of indicators, because this is established by the bodies that are in charge of accreditation. In China, Guo and Li (2018), although they declare the importance of postgraduate studies for the sustainable development of the country and of higher education itself, focus their model and proposals for improvement on the quality of teaching and the scientific level of the curriculum. Also in China, Xu et al. (2022) recognize the importance of the insertion of postgraduates in society for the solution of local and global problems, but they do not take this factor into account in their quality prediction model.

As already seen, the medium and long-term effects of this type of quality management models are usually different from those expected; for example, Patiño and Alcántara (2018) point out that, in Mexico, after a decade of policies aimed at solving the lack of human resources for research and the search for high-quality postgraduate programs, there has been an accelerated increase in low-quality graduate programs that are based in the private sector. Instead, students welcome the reversal or easing of these trends. Also in Mexico, a perception study carried out on students of a Master's in Health Sciences showed differences between the subjects in terms of the level of participation that the students observed in various variables, including the execution of activities linked to the social environment (Rillo et al., 2009). An investigation carried out at the Catholic University of Murcia, Spain (Pegalajar, 2016) showed that the student body favorably appreciates that teachers understand knowledge as a teacher-student social construction, that teaching-learning methods include innovation and solving practical problems, and that what they have learned is useful for their insertion in a society with a high level of complexity.

Based on these analyses, is it correct to make a total turn towards the social-humanist approach, abandoning competitive positioning standards, and flatly rejecting the intention of being ranked among the best universities worldwide?

In our Latin American reality, a university should harmoniously combine the training of professionals capable of meeting the development needs of the countries, the generation of knowledge related to universal values, the learning/adaptation/application of existing technologies and the concrete responses to demands of the environment, with global insertion strategies (Ricaurte and Pozo, 2018). However, turning a blind eye to the existence of rankings, and to compliance with the parameters that govern the world quality of universities today, means excluding oneself from the competition; therefore, program proposals, their management and self-evaluation must take into account both the world standards of the competitive approach and the principles of the social-humanist approach.

It is not a question of introducing radical changes in the way in which the postgraduate studies are projected and managed, but of making the purposes indicated in the programs that are approved, in terms such as interdisciplinary approach to the object of knowledge, link with the productive environment, collaborative work (Cruz, 2014) and others, stop being good intentions and become real work objectives. These transformative actions should be accompanied by an accreditation system that gives a greater role to linking postgraduates with society and solving their problems at a local, regional and national level, as well as a forensic fight so that these criteria gain space in global accreditation systems.

CONCLUSIONS

Based in the information reviewed, it is concluded that in postgraduate quality management worldwide the competitive approach predominates, with the tendency for universities to position themselves on the basis of academic and scientific standards. Graduates from these programs sometimes find it difficult to solve social practice problems, which require a holistic vision, and show a lack of commitment to sustainable development.

The social responsibility of universities, and postgraduate studies in particular, implies a commitment from training, research and the application of technologies in solving local, regional and national problems, which can only be achieved with a solid humanistic-social approach.

Latin American universities must combine compliance with positioning standards in competitive rankings with postgraduate social responsibility objectives, and assign greater weight to the latter in accreditation systems