INTRODUCTION

Archaeology is rapidly increasing its action range when it approaches other historical moments linked to modern and contemporary societies, becoming much more accustomed to processes closer to current societies - the case of the Archaeology of the Present, for example. Cities became a great source of archaeological sites. It became what is refereed to as Urban Archaeology. As Funari (2005) points out, the equation Historical Archaeology = Urban Archaeology does not apply to the complexity of urban space formation.

According to Zanettini (2004), urban archaeologists also study cultures who existed before to the formation of cities. In many respects Historical and Urban Archaeology are mistaken as the same specificity of a broader field, Archaeological Science. Although it came from Historical Archaeology (Staski 2008), and indeed most of researches in cities deal with historical archaeological sites, it is necessary to highlight the potential existence of prehistoric or pre-colonial contexts, under the city’s urban fabric. As an example, the Sítio Arqueológico Morumbi, in São Paulo city, a lithic workshop in this case existed within what was once a concrete jungle. Similar case happenes in New York, close to the Hudson River, and in many other megalopolis (Salwen 1978).

The presence of prehistoric or pre-colonial contexts in an urban environment underlines the importance to considering the city itself as part of the formation process of an archaeological context. If, as Schiffer (1995) proposed, the natural processes, n-Transforms and the cultural processes, c-Transforms, are deeply considered by archaeologists, the development of the city will be part of the the cultural formation process of the archaeological record.

. (Schiffer 1995:48)Transformations are modeled through the use of two sets of archaeological laws. The first set, “c-transforms”, describes the cultural formation processes of the archaeological record. These laws relate variables pertaining to the behavioral and organizational properties of sociocultural system to variables describing aspects of the archaeological outputs of that system. The laws of noncultural formation processes are termed “n-transforms”

As obvious as it could be, archaeologists must consider both natural and cultural processes of record alteration, post abandonment, when working in urban archaeological contexts. However, in the city, the archaeological context was highly altered by cultural process related to urban development. Therefore, urban development itself expands the preimposed restrictions used for delimitating an archaeological site.

This new perspective does not exclude the first one, coming from historical archaeology (the archaeological site in the city), but expands its understanding, allowing to glimpse cities as a living organism, in interaction and connected. As widely known, an important topic of research among urban archaeologists is urbanization, the general process related to the emergence and development of cities (Staski 2008:07).

As Staski (2008) pointed out, the process of urbanization should be understood in the context of the investigation of an archaeological site, in line with the idea of the formation of the archaeological context, as proposed by Schiffer (1995). This Urban Archaeological postulate questions the own concept of archaeological site as spatial limit, suggesting that the city, the urban mesh, must be treated as a locus, a unique archaeological site.

These two premises, one looking at the archaeological site as independent of the context of urbanization, and the other, looking at the city as a whole, originated the concepts used by Salwen (1978) and Staski (1982) of an archaeology in the city and an Archaeology of the City. While urban archaeologists profess archaeologies in the city, we have not, with few notable exceptions, begun to explore the inherent possibilities in the more rewarding concepts of archaeology of the city (Salwen 1978: 453) and:

(e.g., Salwen 1973). (Staski 1982:9)Advances in methodology, or archaeology in the city (Slawen 1973; Staski 1982), seem to have been given most attention. [...] Urban archaeology seems to have advanced less far, however, in matters of theory and substantive historical research regarding urban phenomena themselves. Although a number of scholars have attempted such archaeology of the city, and in spite of a number of pioneering statements promoting such research

Considering the conceptual division established by both beforementiond authors, an archaeology in the city would be linked to perspectives looking at archaeological sites despite their placement contexts of urbanization; on another hand, an archeology of the city begings from accepting that the urbanization process is an integral part of analysing the research object. In this aspect, however, the idea that concepts mutually exclude each other is not valid, and one could start from both perspectives.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Staski revisited his publication Living in Cities (1982), following-up with Living in Cities Today (2008), reformulating its proposition. In this sense, the second document presents a differentiated statement, one in which both perspectives - of an archaeology in and of the city - are complementary.

In addition, Staski renew its arguments, now permeated by post-processualist postures, highlithing that Urban Archaeology may serve a city aid its urban planners. This new stance was understood as an Archaeology for the City, despite the use of the previous term, Archaeology of the City (Staski, 2008). These concepts are here used together, upon Staski’s approach and perspective.

METHODOLOGY

The intersection between Archaeology and Museology, more specifically between Urban Archaeology and Sociomuseology, falls under the scope of the so-called “musealization of archaeology” (Bruno 1995; Wichers 2011; Tessaro 2014). In short, musealization of archaeology is a research methodology and a contemplation on archaeology and socializing knowledge based on what García Canclini (2011) defines as “nomadic social sciences”. Such encounter, which already stems from multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary sciences at its core, demands for methodologies that allow to move along these diverse paths.

Despite this intersection, specificities of each one of these fields must be taken into consideration, so that no losses occur in relation to the object of research, the archaeological context, and the process of socialization of knowledge. Since this paper targets formulating a concept engrained in nomadic aspects, it is important to present the perspectives that led to its proposal. As this process is in no ways finite, it enable further discussions about the own science where it originated, archeology.

For this exercise, considering the landscape as cultural is of paramount importance and it opens space to the possibility of each person or communit having it particular meanings about it. Also, rescuing proposals from Staski (1982; 1999; 2008) and Salwen (1978), in which urban archaeology should treat the city as an archaeological locus in which an archaeology of, in and for the city, is plays a key role. The current redirectioning of Urban Archaeology and the proposal of an archaeology with the city concept came to light due to the influence of Sociomuseology as part of a research on musealization of archaeology by Tessaro (2014), developed under the scope of a master's degree.

This thoughts, however, do not exclude the above considerations; on the opposite, it includes those of Salwen (1978) and Staski (1982; 1999; 2008) for urban contexts, towards a most comprehensive archaeological discipline, where interaction and communication are integral parts of the archaeological research. “

” (Hodder & Hudson 2003:189).En último lugar, una arqueología totalmente crítica y responsable ha de ser capaz de usar la objetividad y la realidad de la experiencia de sus datos, con el fin de dar forma y transformar la experiencia del mundo

According to Hodder & Hudson (2003), to transform the experience of the world, archaeological data should be related to society: “

” (Hodder & Hudson 2003:189-190).Existe una relación dialéctica entre el pasado y el presente: se interpreta el pasado en función del presente, pero puede también utilizarse el pasado para criticar y desafiar al presente

Zanettini (2004:152) states: “o arqueólogo urbano não tem necessariamente que restringir suas análises aos locais que escava”. And since Archeology is a Science based on multidisciplinarity, it should also be so in contexts of Urban archeology. Adding perspectives of Sociomuseology only expands the reflexive possibilities, as well as the inclusion of insights provided by other Sciences.

Geography is a field of possibilities and concepts like “roughness” (Santos 2008), elements from the past that remain in the landscape, do have added value. Many other proposals also add to a better urban archaeology, such as including perspectives from urbanism, urban anthropology, among others. Hence, this paper think about problems that affect the city's daily life (Zanettini 2004) merging with Staski’s proposal: urbanization is an important topic of research among urban archaeologists (Staski 2008:07).

When dealing with the city, its fragments can be observed, its pieces of the urban fabric, connected through the media communication (García Canclini 2008).

In this respect, museological perspectives that interact with the communicational environment can and should be used when researching about archaeological contexts: “(...)

” (Chagas 2005:18).considerar o museu como ponte entre tempos, espaços, indivíduos, grupos sociais e culturas diferentes; ponte que se constrói em imagens e que tem no imaginário um lugar de destaque

Chaga’s perspective combining with Staskis, Salwen, Zanettini and Garcia Canclini, it becomes clear, as proposed by Ferreira (2008), that social relations involve artifacts: “

” (Meneses 1983:112).cultura material que poderíamos entender aquele segmento do meio físico que é socialmente apropriado pelo homem

Discourse (Foucault 2007) can be understood as a form, a modus operandi. Doing something in a certain way, such as the simple act of walking, is itself a discourse, a culture that is created, thought out, modified, assimilated, signified and re-signified by individuals.

History’s stratigraphic piling (Certeau 2008) opposed to a history that is divided from the present, also supports the need for broadening concepts related to researching the city from archaeological and museological perspetives:

(...) a historiografia separa seu presente de um passado. Porém, repete sempre o gesto de dividir. Assim sendo, sua cronologia se compões de “períodos” (...) entre os quais se indica sempre a decisão de ser outro ou de não ser mais o que havia sido até então (...). Por sua vez, cada tempo “novo” deu lugar a um discurso que considera “morto” aquilo que o precedeu (...).

. (Certeau 2008:15-16)Muito longe de ser genérica está construção é uma singularidade ocidental. Na Índia, por exemplo, “as novas formas não expulsaram as antigas”. O que existe é o “empilhamento estratigráfico”

The above allows us to understand the present of the city must be understood as an archaeological context and a systemic context (Schiffer 1972). The city indeed must be treated as a locus, in which present meanings and discourses are part of the interpretation of the past. The landscape, in this aspect, becomes an important object in the understanding of what the city is, not only its significant places (Zedeño & Bowser 2008), but the discursive and political actions that take place there.

Schiffer's (1972) concepts of archaeological context and systemic context serve to reflect upon the city: systemic context labels the condition of an element participating of a behavioral system. Archaeological context describes materials that have passed through a cultural system, now the objects of investigation of archaeologists.

RESULTS AND DICUSSIONS

Cities, therefore, are archaeological and systemic contexts in coexistence and interaction, which makes the systemic context part of the archaeological work, in opposition to the idea that the archaeologist only reflects on the former. It is in this aspect that the city must be thought of as a locus, as we are dealing with living artifacts that shape the landscape, buildings that are reused and unabated landfills that are still functional.

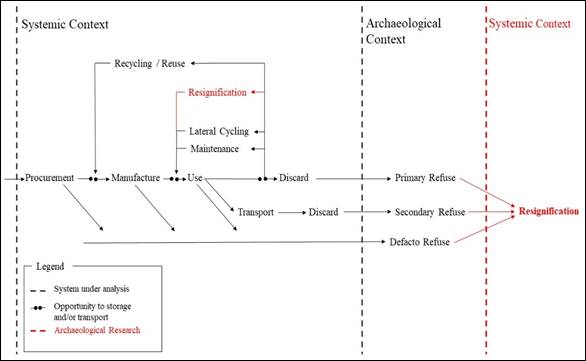

Below, I present the table that synthesizes the ideas of this reflection, using as a basis figures presented by Schiffer (1972):

Source: Schiffer (1972:158-162)

Figure 1: Based on Figures 1 and 3 of Schiffer, about process in Systemic and Archaeological Context; red parts inserted, about process of resignification in archaeological research or maintenance

We are dealing with the manipulation of artifacts from an archaeological context, returning to a new systemic context, and therefore assigning new functions through re-signification. An archeology that is unconcerned with this recycling/re-signification, of exhumed objects placing them in a technical reserve without a new functionality, is practically relocating them again in an archaeological context, as we would be dealing with abandonment again, or as Bruno (1995) pointed out a stratigraphy of abandonment.

This relationship with post-research abandonment becomes more evident at the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century with the increase of work in preventive archeology and is explicit in the historical development of Brazilian archeology and museums as stated by Wichers (2011).

The process of this thought and reflection was linked to the affirmation of Urban archeology as a field of research, since professional colleagues constantly stated that this was not Archeology. It was in this defense process that the approximation with aspects of Sociomuseology and the musealization of Archeology occurred, something even often overlooked by these colleagues, who practice their research and profession by the logic of the stratigraphy of abandonment (Bruno 1995).

Recovering the concepts of systemic context and archaeological context (Schiffer 1972), serves as an affirmation to combat these two issues: urban archeology being disregarded by colleagues as an invalid field; and the abandonment process extravasated by ignoring a process of resignification and communication.

In short, these two areas, one of Archeology and the other of Museology, in the process of musealization of Archeology, have in the urban context a rich theoretical reflexive potential to discuss current issues in Archeology. They serve as a rich laboratory for experimentation.

This reflection led to the exacerbation and reconfiguration of a concept of Urban archeology, archeology with the City (Tessaro & Souza, 2011; Tessaro, 2014), which is currently directed towards understanding the existing approach to Public archeology.

This approach occurs mainly in the process of resignification, already expressed earlier. But it is worth highlighting it as: a representation of the past in the present, supported in the cultural materiality, but only in the process of resignification, is that they become history (Machado 2017). More than history which is something that is in the present, the resignification allows new functions to be assigned to this material culture. “

” (Machado 2017:97).Essa construção baseia-se tanto no seu passado, na sua tradição cultural, quanto no seu presente, nas suas demandas cotidianas e políticas, apresentando-se como perspectiva de futuro

This process of re-signification, which takes place in the present, also contains the past and also the future, thought in the process of socialization/musealization is what generates approximation with aspects of Public Archaeology, or even Collaborative Archaeology. However, to exercise these approaches considering the context of an entire city, we need to perform a democratic, non-exclusive look, or even as some archaeologists call in their research, a cosmopolitan (Meskell 2009), or citizen (Colwell-Chanthaphonh 2019) thinking.

Matsuda (2016) indicates in the brief history made in his article, that Public archeology is divided into four approaches: Educational, Public relations, Pluralistic and Critical.

. (2-3)The educational approach aims to facilitate and promote people’s learning of the past on the basis of archaeological thinking and methods; the importance of protecting and conserving archaeological remains can also be a subject of learning in this approach. The public relations approach aims to increase the recognition, popularity, and support of archaeology in contemporary society by establishing a close relationship between archaeology and various individuals and social groups. The pluralist approach aims to understand the diversity of interactions between material remains and different members of the public; it treats archaeology as one way of making sense of the past and considers how it can meaningfully engage with various other ways of interacting with the past. Finally, the critical approach engages with the politics of the past (Gathercole & Lowenthal, 1990), typically by seeking to unsettle the interpretation of the past by socially dominant groups, in particular ethnocentric and elitist groups, or to help socially subjugated groups achieve due socio-political recognition by promoting their views of the past

In a way, the path of Sociomuseology, inserted in the context of Urban archeology, promotes a greater or lesser approximation with the four approaches at a time when archeological methods and practices become instruments for education/reflection of the city; when it proposes the establishment of socialization, even if only through an exhibition, it is making knowledge/resignification accessible to the population.

When this process of resignification is centered on present urban issues, it turns to the pluralist, or even diversified, aspect of society; and finally, when they propose to reflect on these issues, critical thinking about the past is inserted. However, these divisions are not rigid, but permeable and interchangeable with each other.

In this respect, the idea that Archeology is serving the city is overcome, but rather, that it starts to compose the urban social context in which it is inserted, discussing the city in its urban issues through Archeology. And that's why the reconceptualization of an archeology with the City. However, this concept inserted in the perspective of Public archeology, faces different problems in its theory and practice, depending on the city.

In a city of large proportions, millions of inhabitants, the task of choosing one social group would automatically generate the exclusion of another; seeking to remedy, perhaps this anti-democratic attitude, the use of urban problems, even though at different levels, is something that impacts the city as a whole; as an example, we could mention the issue of mobility. It is up to the archaeologist to know how this could be discussed through archaeological contexts.

As a brief practical example, which will not be discussed in depth here, since the proposal was restricted to theoretical and methodological reflection, one can cite the research developed on the archaeological site Quadra 090, a block in the historic center of the city of São Paulo (Tessaro 2014). This is a diversified context of the transition from the 19th and 20th centuries, where there were domestic units and a productive unit. A period in which the city of São Paulo was going through its first intense process of growth and urbanization (1870-1930).

Considering all the issues of cultural transformations that this site went through, leaving persistent marks, three aspects were related to urban problems of the city in the present and could be used to influence a critical thinking in society: the practices regarding trash; the stratigraphic configuration; and the social identification. In addition, the site was located in the place in the city known as Cracolândia, where crack users occupied the streets.

The practices in relation to garbage, establish parameters to address the concept of hygiene in development in urban society, represented by the presence of garbage cans built in masonry, in the archaeological context. It was possible to think about the development of hygiene and how it extrapolated the material and domestic aspect, directing itself from society to society, giving rise to Cracolândia. This would be a place of social hygiene, or disposal of “human waste” (Bauman 2005:47).

Later, what was approached was related to the stratigraphy of the archaeological site, in which successive layers of asphalt and concrete were found superimposed. This aspect, looking at the stratigraphy as an artifact, makes it possible to think about two present issues in the city: soil sealing and urban mobility that prioritizes cars. During the research period, 2013, there were several protests in the city related to the issue of urban mobility and price increases in public transport.

And finally, these two themes and the physical and representative aspect of the material culture of the archaeological site itself lead to a discussion about identity in the city, the feeling of belonging or not. Where society dismisses people from itself, where the mobility hindered by the accumulation of streets and by the flooding generated by the sealing of the soil generates the discomfort and the feeling of not belonging. Which in turn influences the feeling of identity.

This brief example is further explored in the master's dissertation “

” (Tessaro 2014) and which is now being deepened in the context of the doctorate. With the inclusion of other contexts, including a lithic workshop, Sítio Arqueológico Morumbi, which is located within the City of São Paulo.Pedaços de uma Paulicéia Espalhados pela Urbe: musealizando uma Arqueologia com a Cidade

CONCLUSIONS

An archeology with the City must be aware of considering the city as a locus, as it deals with living (systemic) and abandoned context (archaeological), which have direct relation with the city's landscape. These contexts, even if not visible, are in the city's daily life, present in its development. When dealing with the systemic context, archaeologists deal also with the social relations present in a place, not only within the artifacts. At the same time, it also deals with the cultural context inserted in the daily life of the imagination, perception and resignification of the individuals who use this space.

In this paper, I aimed at reflecting upon an Archeology committed to the city, following Hodder & Hudson (2003) proposal of an Archeology that thinks, discusses, and criticizes the present, one that is part of the future, to whom communication and extroversion contribute to the construction of this same future. Exercising a more humane and Democratic archeology, not along the same lines as an Ethno-archaeology or a Public/Participatory archeology - because in a big city, we would be selective, by prioritizing one group over another; but transforming the systemic context, whether part of resignifying practices or not, through the analysis of social and urban problems, urban archaeologists will be initiators of discussions about the city. In short, an archeology with the City