Introduction

Latin America has increased the population enrolled in all levels of education but still faces challenges in educational quality and equity. School leadership has been recognized as an important factor to increase student’s achievement and overall school improvement (Robinson, 2007; Bellei, 2014) especially in vulnerable contexts (Hallinger & Heck, 1996; Leithwood, 2008). For this reason, most Latino countries have attempted to implement standards and competency frameworks for school leadership and teachers in management. Ecuador has designed “Estándares de Gestión Escolar y Desempeño Profesional Directivo y Docente” (Dirección de Estándares Educativos, 2017), Peru committed to “Marco del Buen Desempeño del Directivo” (Ministry of Education Perú, 2017), Colombia implemented the "Manual de funciones, requisitos y competencias para directivos docentes” (Ministry of Education, 2016). These standards are a valuable asset and they are used in selection and continuous assessments of school principals and teachers in management. They provide objective and clear benchmarks to support principal´s assessment and ideally to ensure accountability (Weinstein & Hernández, 2014; CEPPE, 2013).

However, a weakness they may have is the lack of context as they do not consider the type of schools being served by principals. As an example, in Latino countries there are only a few attempts to implement standards and competency frameworks for administrators in technical and vocational schools (TVET) but they are still general to be applied to this type of schools. TVET education may need by its own nature different management standards. This type of schools train students in general competencies but also offers training for occupational competences. They serve a population that usually lacks economic and cultural capital who may need practical training to work as soon as possible. Furthermore, they need a fast and flexible way to acquire skills, as they may not continue their academic education after high school (Galeano, 1999)

An example of specific guidelines for school principals in the management of TVET schools was implemented by Council for Technical Education / University of Labor “Consejo de Educación Técnico Profesional/Universidad del Trabajo” from Uruguay (CETP/UTU), however it has not become a gold standard of management in Latino countries. The main idea is that management requires to lead innovation projects, and not just the typical education project delivered in general education schools. Besides, school management requires to lead a body of teachers who may not be trained for vocational education and who may not have adequate pedagogical skills. Finally, school leaders in TVET education have the commitment to provide relevant education to respond to the needs of employers which means, they have to make sure students are learning marketable skills. Management will also lead to improve school quality as they may compete for funding, they may be pressured by high stakes testing and they require to integrate a diverse body of students (with cognitive or physical disabilities, varying capacities for learning and background, etc.).

The present article argues that TVET education requires leadership that goes beyond instructional or distributed leadership and entails capacities to help develop technical students in the contexts of educational systems that are far from articulated and lacking to accomplish the promise of value to educate the technical workforce of the future.

“Leadership” in the context of Latino schools

In this section the aims and scope of the school leader role are described. School leadership may mean similar chores and aims within the diversity of Latin American countries (Montecinos, Bush & Aravena, 2018). To start, it is important to make clear that Latino America refers to countries in the Western Hemisphere where romance languages such as Spanish, Portuguese and French are predominantly spoken. These include high density population countries such as Brazil (204.519.000 million people), México (127.500.000), Colombia (48.218.000), Argentina (43.132.000), Perú (31.153.000) and Venezuela (30.620.000). The remaining Latino countries have a population under 18.000.000 of people. The overall population of Latino countries reached 617.311.000 million in 2019. All Latino countries have develop their own systems to provide education as a public service implemented by private or governmental agencies. These countries have also developed an emphasis in school improvement and effectiveness following the Anglo Saxon model of instructional leadership (planning and coordination of teaching and learning) and distributed leadership (others beside the principal taking on the leader role) (OECD, 2016; Spilane, 2005; Weinstein and Hernandez, 2016)

Currently, in most Latin American countries a teaching qualification and teaching experience are often insufficient attributes for new principals facing new tasks and challenges (Bush, 2018). Principals are expected to establish goals and expectations, perform strategic resourcing, planning, ensuring an orderly and supportive environment and most importantly coordinating, evaluating and promoting teacher´s development (Leitwood, et al., 2008; Robinson, 2007). Furthermore, school managers in Latin America and around the globe have been charged with new responsibilities. They are now required to go further than merely meeting external accountability mandates, and they strive to improve the teaching and learning of all students creating school conditions that foster student´s outcomes (OECD, 2013).

It is also expected that school leaders succeed at a series of responsibilities, full of novelty, such as making decisions based on school and system-wide data, for example, by exploiting data analytics (Sergis, Sampson & Giannakos, 2018). Also they should promote student´s mental health and safe school environments (Dematthews & Brown, 2019), and they are expected to make greater contributions to staff capacities such as mediating teacher´s commitment, resilience and effectiveness (Leithwood, et al., 2008). Leadership also takes place in contexts that were not common before. As education expands around the globe and reaches new groups of people, innovations such as open and flexible learning, mega universities and on-line schools have called for a renewed leadership instead of management (Latchem & Hanna, 2001).

In OECD countries, school leaders are expected to raise levels of student performance, close the gap in achievement between different student populations, providing inclusive education to special needs students and immigrant children, reducing drop-out rates, and achieving greater efficiency (OECD, 2008). Thus leadership has been redefined as ¨the task of influencing and motivating others to achieve multiple shared goals and objectives ¨ (p.56, Leithwood, Sammons, Harris & Hopkins, 2006). This involves not just the principal´s role, but the interaction and cooperation with others in the school (Ministry of Education of Chile, 2015). It has been stated that in Latino countries school leadership policies are at an early stage and the current definition of leadership is still a translation of the Anglo Saxon discourse of school instructional management (defined by decentralization, autonomy, and accountability), and thus a regional local response to the goal of promoting a renewed

context-based leadership must be addressed in these countries (Weinstein & Hernández, 2016).

Table 1 presents a brief overview of the educational systems in Latino countries and the role of school leaders in the region. Across all countries, school leadership responsibilities include managerial (abidance to rules and administrative procedures, human resources management, etc.), instructional (classroom monitoring and feedback, evaluation of teacher performance, participation in the professional development of teachers) and social (involvement with school actors and extended context such as public organizations). Although responsibilities may vary per country in scope and aim, there are common characteristics of school leadership in Latin-America. First trend, is the lack of pedagogical authority of the principal in almost all Latino countries. That is the belief that “the teacher is an independent professional, who is not subject to the pedagogical authority of the principal. In other words, their role in supporting, evaluating and developing of teacher quality is minimal” (p. 248, Weinstein & Hernández, 2016). A second trend is a contradiction among regulations and standards, which means that Competency Frameworks “show little alignment with the major responsibilities that educational regulations confer to principals” (p.249, Weinstein & Hernández, 2016). Another common tendency in Latino systems is the little autonomy and restriction on decision making on budget and school resources conferred to principals. Finally, school leader´s in- service training and certification is not aligned with Standards and Frameworks of school leadership yet. Despite these trends, Latin American countries have a strong potential for quality improvement. An example is the incipient and progressive professionalization of the principal´s role in schools:

Many school systems have made efforts in installing new, more technical and less discretionary principal recruitment processes, with predefined profiles, public procedures and collective decision making instances. Additionally, in some cases, performance appraisal procedures have been implemented while in others, they are being currently being discussed and designed. Lastly, almost all systems have introduced monetary incentives to better reward the position and positively differentiate it from the status of classroom teachers (p., 258, Weinstein & Hernández, 2016).

Table 1 Brief review of educational systems in Latino countries.

| Country | Educational system | Leadership role |

|---|---|---|

| Chile | Central-local governance model: Ministry of education orients and regulates all public schools in terms of pedagogical matters. Administratively, decisions about infrastructure, personnel and budget are the responsibility of the Municipal Department of Education (DEM). There exist a national and unique curriculum and standardized tests at different levels of education. The curriculum is centralized as well as pedagogic development, monitoring and supervision of schools. It has an interesting model based on high school performance expectations. TVET education is provided by public schools (not private) and tertiary level TVET education is provided by public and private institutions. | Leadership role is defined in the Competency Framework for “Good School Headship and School Leadership” or “Marco para la Buena Dirección y el Liderazgo Escolar” (2015). There are also a set of Performance Indicators for Schools and Administrators (2014) and performance agreement contracts for public schools. Law 201.501 provisions for affording principals greater autonomy in decision-making (staff hiring/firing but up to a 5%) |

| Argentina | Model of shared governance between the national government, provinces and federal districts. There is a central nationwide authority (Ministry of Education, Culture Science and Technology). Private providers at all levels generate their own funding. Education provision is managed at state or provincial level. TVET education in secondary schools lasts 6 years. Argentina developed a Law of Technical Education (Law No 26.058) that regulates TVET in all levels of education. | High number of school leader´s responsibilities (up to 63 different activities). Leadership dimensions include instructional, administrative and social. However, instructional responsibilities are well defined. |

| Brazil | With the exception of tertiary education, Brazil’s education system is largely decentralized to the states and municipalities. All levels of government drive education policy. The System requires better articulation between levels of education, greater flexibility and efficiency in governance and management in schools. It has developed a National Curriculum and performance standards (SAEB Proficiency Scale). Compared to other countries, a very low rate of students enroll in TVET education (8% compared to 46% OECD average). | Focused definition of roles with emphasis in goal setting and instruction. School leaders in Brazil report that they frame and communicate their schools’ goals, co-operate with teachers to resolve discipline issues, develop and promote instructional improvement and support professional development more than their peers in other Latino countries. |

| Colombia | Complex (including several bodies and agencies) and decentralized system with national standards for education but different curriculums in schools. Varying levels of coordination among national and local levels. It has recently implemented a full day schedule and technical education can start in grade 9th (15 years of age). It has also implemented a National Framework of Qualifications to recognize and validate formal and informal learning. Responsibility for the system of education is shared between the nation and territorial entities. TVET education is guided and mainly provided by the SENA, an institution dependent on the Labor Ministry. | Wide range of responsibilities for principals: goal setting, organizational conditions, administration and instruction. Principals are regulated by the National Ministry of Education and local governmental agencies (Local Secretary of Education). The country has Leadership Standards (“Manual of functions, requirements and competences for teaching managers”) (2003) based on functional and behavioral competencies of principals. |

| Ecuador. | Centralized authority of the Minister of Education. The Ecuadorian constitution requires that all children attend basic education. The high school level is called “Bachillerato General” or “General High School” which does not differentiate among TVET or Academic students. TVET students receive additional training and the same curriculum as academic students. Ecuador recently created a National University of Education. | A framework for leadership was developed in 2011 (core competences are leadership, curriculum, management and climate). The principal´s role has low emphasis on instruction but wide variety of responsibilities: from administration to management and social participation and involvement. |

| México | Upper secondary is mandatory. Local territories may adapt the national curriculum including local contents. To increase territorial outreach, administrative and legal services have been decentralized to sub-regional offices. However, municipalities have only a little role in issues such as educational infrastructure. It has develop content and definitions of expected learning outcomes, but it still does not have National Standards for School Leadership. Teacher Union play a major role as stakeholder on personnel decisions (appointments, hiring, firing, etc.). “Evaluación Universal” is an assessment for the educational workforce. The New Educational Model (Nuevo Modelo Educativo, 2017), ensures that all students are able to develop the skills required in the 21st century. | High number of responsibilities and emphasis on administration and very low on instruction. The system still lacks a widely accepted framework defining standards for the teaching and leadership roles. The General Law of the Professional Teacher Service (2013) aims to professionalize school leaders by introducing a transparent selection and recruitment process, as well as an induction process, during the first two years of practice. School leader appraisal in Mexico also became legislatively mandated. INEE became in charge of the approval of the evaluation tools for this. |

| Perú | The Ministry of Education is the central jurisdiction regarding formulation, implementation and supervision of the national policy in Education. It has an emphasis in intercultural Education. There are private and public providers of Education that vary in quality. TVET education is offered in the last 3 years of High School and it is differentiated from the education students receive in the academic track. | Limited emphasis on instructional leadership and very low and delimited range of responsibilities. It has develop a Framework for Principals (Framework for Good Management Performance) which is extended to the role of leaders in TVET education. |

| Costa Rica | It is centralized by the Minister of Public Education. It has been successful at providing universal access to basic education. It implemented measures to improve leadership in schools and a reformed school supervision in 2010. Quality assurance is school lead, but poor outcomes in learning are persistent. School principals undergo assessments but results are not used for accountability. There is a high level of vocational education involvement but it is still highly academical, as all students pursue the assessment to obtain the Bachillerato title. | Leaders have a limited role in instruction. Supervisors stay focused on procedural compliance. Leaders are not accountable for learning outcomes or improvement. |

Source: OECD Reviews of National Policies for Education, 2010.

Standards and Competency Frameworks for Administrators used in Latino Countries

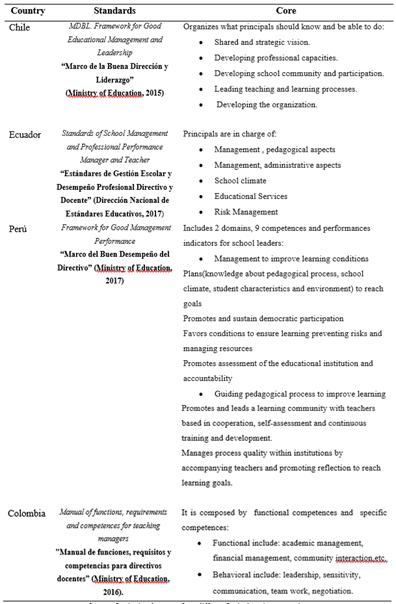

In Latino countries the standards and frameworks of competency for school leaders are the definitions that systems adopt to establish the main duties to be performed by principals (Weinstein & Hernández, 2016). In the region the policy for school principals has been governed by the Ministry of Education, but there are no presence of specialized institutions or specific units to train and evaluate school leaders. Also, in most Latino countries there is relative autonomy for affairs related to private school´s principals. Table 2 introduces a summary of “Standards and Frameworks of Competency for Administrators” developed in some Latino countries.

In Chile there is an attempt to consolidate a strong body of school principals who are able to participate in school life and who are chosen based on merit by the government. They are public servants and their work is oriented by the MDBL (“Framework for Good Educational Management and Leadership”). This frame is making a change as it strives to enhance the principal´s participation in the pedagogical aspects of teaching and learning over and above focusing on managerial aspects of leadership. It has been reported that leaders in Chilean schools present a high turn-over rate, which is due in part to the burdensome load of responsibility and the lack of professional development (they have to go thru the ¨”swim” or “sink” experience) (Valliant, 2011).

Chile has advanced in defining and measuring effectiveness in school leadership. Leadership in Chile is the “practice of improving” not just a personal inherent attribute or a static competence. Instead, it is a group of daily actions based in knowledge, skills, habits that may be taught and learnt (p. 10, Mineduc 2015). And Chile has focused on evidence regarding the importance of increasing pedagogical leadership instead of school management (Weinstein et al, 2012; Leithwood, Sammons, Harris & Hopkins, 2006; Robinson, 2009). It also has raised expectations and regulations tying principal´s activities to student´s outcomes. For example, the implementation of a nationwide System of School Quality Assurance (“Sistema Nacional de Aseguramiento de la Calidad de la Educación Escolar”, SAC), which is composed by three agents: a superintendence agency, an assessment agency and a curricular review and approval agency. All work together in coordination with the Ministry of Education to help improve and support schools and their principals.

Table 2 Standards and Frameworks of Competency for Administrators in Latino Countries.

Source: Institutional sources from different Latin American countries.

Also Chile is a particular example of the way laws and public policy are improving education and educational leadership. The Law 20.501 has stated new ways to select and recognize school leaders, which does not over -emphasize the selection based on formal education but experience and also implements a very selective process. Also, it is stated in the Chilean Law that principals are responsible for ¨directing and coordinating the educational project at their schools¨, they are able to build up their own directive teams and are free to remove up to 5% of school teachers. The Chilean law also recognizes that leadership depends on contexts and is contingent to aspects such as school vulnerability and conditions. Finally, Chile has implemented annual assessments of principal performance which is not implemented in all Latino countries except in Colombia, with consequences to principals. (Weinstein and Hernández, 2014).

For Chilean leaders the Competency Framework establishes 5 practical dimensions (shared strategic vision, professional capacities, leading teaching and learning, developing school community/participation and managing the school) and 3 personal resources (principles, skills & professional knowledge). The core principle of the framework is that principals must be involved in monitoring and aligning curriculum and instruction across all levels. Teaching and assessment are also synchronized and coherence and continuity should be reached. Also principals must base their actions in ethics, social justice and integrity. According to Weinstein & Hernández (2016), “The definition of functions of school directors existing in Chile corresponds to an exception within of the Latin American cases, distinguished by its focus on a few relevant responsibilities and pedagogical leadership” (p. 56, 2014).

This leadership encompasses tasks such as organizing the pedagogical work of teachers, supervising classes and classrooms, controlling for learning outcomes, advising teachers, directing and controlling for the academic program and its implementation, and motivating professional development of teachers.

Ecuador implemented a Framework of competency for principals that is tied to the expectations of school and teacher´s performance (Dirección Nacional de Estándares Educativos, 2017). This framework promotes coordination among three levels (teachers, principals and schools). For example, teachers are required to plan ahead according to the curriculum and school project while the school has to tailor an annual curricular plan, and the school leader is urged to manage the implementation of such plan. Also, while teachers inform the malfunction of infrastructure and promote proper use of it, school leaders must manage infrastructure and supervise its use while schools must storage records of maintenance and control of infrastructure use.

Regarding Administrative Management school leaders in Ecuador are required to be responsible for management of the school project and are held accountable for communicating and connecting with the extended school community. Also, they are in charge of human resources management by providing incentives and training to school personnel and oversight of duty compliance according to the “Manual of Academic and Administrative Processes”. However, they are not responsible for hiring or evaluating their own personnel. Additional responsibilities include management of infrastructure and oversight of data analysis and delivery to Ministry of Education. Pedagogical Management, includes responsibilities such as coordinating the annual curricular plan and the institutional curricular plan, and follows up the development of curricular planning (reviewing teacher´s planning or micro-curricular planning), and oversees the development of teacher and student remedial plan. School climate responsibilities for school leaders include promoting a healthy social environment, relating to other schools, supervising the code of school coexistence, implementing research in cooperation with other institutions, and participation in projects to benefit the community. Additional functions of school principals include Coordination of the delivery or operation of Complementary services that the institution offers and School risk management.

This set of standards for principals are intended to be applied to all public schools. It is interesting that standards targeted to the school principal do not promote a distributed leadership among school actors (as well as it is stated in the national education law or “Ley Orgánica de Educación Intercultural”). It also has a combination of pedagogical and management duties but it is not expected that pedagogical duties are core to the principal´s role. In words of an Ecuadorian school teacher:

When analyzing the practice of school management in Ecuador, there is a personal direction with little participation of the educational community (among others, teachers, students, families) and a practically null democracy for decision making. In short, the managerial function in Ecuador continues on administrative and / or managerial lines, which responds to a management profile (p. 27, Rodríguez, 2017).

Perú has developed a Framework of Competency for Administrators (“Marco del Buen Desempeño Directivo”), intended to orientate the selection, assessment and training of educational leaders (Ministry of Education, 2014). Perú has also introduced a law (Law 29944 or “Ley de Reforma Magisterial”) to establish a Program for Professional Development of School leaders (“Programa Nacional de formación y capacitación de directores y subdirectores de Instituciones Educativas”) focused in principals, principal assistants and TVET -technical and vocational- school leaders. It also devised a system for School Management, including assessment for selection and incentives to school leaders. All these changes are aimed to develop a structural reform of the school as an institution focused in pedagogical and distributed leadership. Although Peru is a pioneer in emphasizing the importance of pedagogical leadership over administrative leadership in Latin-America, in Chile it has already been stated in the law that principals should supervise teachers in the classroom and have more decision power over teacher body in matters regarding instruction.

The standards and framework for school leaders in Peru are organized in domains, competences and indicators. The latter are specific behaviors that demonstrate the school leader´s competence. There are 2 competences emphasizing the importance of instructional or pedagogical leadership: Management to improve learning conditions and Guiding pedagogical process to improve learning.

The first competency includes a set of actions that demonstrates the active role of the school leader: evaluates school climate, designs assessment instruments, develops diagnosis, promotes participation, solves conflicts, manages resources and risks within the school and conducts continuous quality improvement. Among these actions, “managing” or “leading” is only mentioned once (“providing direction to the administrative team”). The second competency encompasses actions to promote a learning community with the teachers based in mutual collaboration, professional self-evaluation and continuous training towards improving the pedagogical practice and ensure learning achievement. It also encompasses monitoring of assessment practices and teaching methodologies.

Colombia also developed a set of Standards for Principals as managers. It encompasses two types of competences: managerial (functional) and behavioral competences. Functional competences for leaders are associated with the direction and organization of operation of institutions and educational establishments. The actions related to management performance are: direction, planning, coordination, administration, orientation and programming in schools. Principals have to accomplish almost 32 activities ranging from supporting the implementation of parenting programs within the school, developing risk management strategies, managing accounting responsibilities, improving teaching methodologies and giving feedback and training opportunities to teachers.

On the other hand, behavioral competences include: Responsibility for personnel in charge, skills and professional aptitudes, responsibility for decision making, and innovation in management. Although the standards are used for assessment of principals, they are not tied to specific training. Also, the standards promote innovation in leadership giving space to leaders to change their practices to benefit schools. The core of the leader’s role is to orchestrate and coordinate actions to develop the Institutional Education Plan (which contains the mission and vision of the institution and plan for immediate and long terms in schools). This goal is accompanied with actions to improve teaching but high expectations of student outcomes are not considered as a goal of leader´s responsibilities.

Meaningful experiences in TVET school´s that required management commitment in Latino countries.

Schools training students in technical and vocational education have a major challenge. They have to overcome difficulties arising from schools as complex organizations, and also they have a promise of value which they have to commit to. A TVET school educates vulnerable students who may want to start working immediately, who are not able or willing to continue their education and who want to learn something useful and practical additional to general knowledge. Facing these needs, leadership as defined by the Frameworks and Standards of competency has to go beyond duty.

Principals can inspire change and can orient school communities to shared views. If a school desires to train individuals to work or to continue their TVET education in higher education (College or Technical Higher Education), schools have to get students ready for future challenges. As an example, Chile has been working in programs to articulate the TVET high school with future work and career goals. One of these programs is developed by “Telefonica” (a major communications provider) and Duoc-UC (a Chilean TVET higher education institution). They are designing curriculums with the support of school principals to help improve the skills and knowledge of students who are trained in the field of Telecommunications. Thus, the students undergoing the program can be hired by the company as soon as they graduate from high schools. They may also continue in Technical Higher Schools to obtain an upper degree in Technology. A second Chilean experience involves principals and schools that train students to work in the field of the mining industry. Under the joint association of the CORFO (Association for the development of industry) and “Fundación Chile” (an NGO), the aim is to train students from high schools to higher education. These students are being acknowledged for their learning in the field. This serves the purpose of articulating the levels of education and providing a more enriched experience of learning to students. Chile is an interesting model of what TVET education in Latin America should be in the future.

Peru has been the first of all Latino Countries to emphasize the importance of centering school leadership in pedagogical goals. It also has a strong emphasis in reflection and promoting goal achievement in the context of schools. Although the results of Peru have not been competitive respective other countries participating in OECD´s PISA program (OECD, 2018), Peru has grasped the importance of leadership centered in outcomes and learning. It is also important to notice that Perú has attempted to declare specific goals for principals in TVET schools.

In Mexico students in schools can go through one of three streams: an academic stream (Bachillerato general), a technical vocational stream (Profesional técnico), and a stream which combines both general and vocational education (Bachillerato tecnológico). All three streams lead to the award of an upper secondary diploma (certificado) and can provide access to higher education. Recent education reforms have aimed to boost technical education in Mexico, such as the introduction of the dual training system in 2013 (OECD, 2018). It is based in combination of school and work-based learning. In order to implement a dual training system, school leaders have to be involved with the needs of industry and students to supply for adequate training going further than the mere compliance with instruction based on a TVET -technical and vocational- school curriculum.

Finally, in Latin America, Reduca (Red Latinoamericana de Organzaciones de la Sociedad Civil por la Educación) is looking to improve the training and development of school leaders in Latino countries. This public-private partnerships around Latino America have built a Community for Shared Knowledge in School Leadership (“Comunidad de Aprendizaje Latino Americana de Liderazgo Escolar”) as a means to contribute to School Leaders in all Latino countries. It puts together different organizations such as Empresarios por la Educación (Colombia), Todos por la Educación (Brasil), Educar 2050(Argentina), Educación 2020(Chile), Juntos por la educación (Paraguay), Grupo Faro (Ecuador) among others. They have been recognized by UNESCO (2015, 2016) Overall, they are initiatives to promote standards of leadership performance adapted to local needs and context. Other initiatives to improve leadership include PREAL (Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas) which has supported the formulation and piloting of a set of competencies for school principals in Panama and one experience in Dominican Republic with the purpose of strengthening leadership capacity at district and school level(Avalos, 2011)

Suggestions regarding the relevance and possibilities of the standards for an adequate management in TVET education

The first Latin American study regarding school effectiveness included 5.600 students, 250 classrooms and a hundred of schools across 9 Latino countries (Murillo, 2007). It confirmed that across Latin American countries, a leadership focused in pedagogical matters instead of management has an impact in the learning of Latino students (it increases in 0, 55 score points in Math and 0,42 in Language Arts in standardized test (TERCE)). If leadership is an important leverage for school improvement, TVET education may require a leadership that faces the challenges of this kind of education.

Table 3 Proposal for TVET Leader Competency Standards

Source: Institutional sources from different Latin American countries.

Commitment to Skills Development. TVET leaders have to make efforts to promote the development of skills, both cognitive and socio emotional. Cognitive skills, including critical reasoning, problem solving and most importantly the capacity for self-learning. Today, Latino youth are lagging behind 1 to 5 years in reading and math compared to OECD countries (OECD, 2018). School leaders have to compromise to help these students commit to learning and to make sure they obtain a level of skill and competence. An important purpose of TVET education and a measurable outcome is employability. Thus TVET leaders have to promote the acquisition of marketable skills. To this end a standard for TVET leaders is not just to keep up with enrollment and avoiding students drop out, but increasing the number of students that successfully complete their TVET education and receive meaningful training and experience. For example, in Chilean TVET schools, students complete their high schools obtaining their diploma, however, in many cases students do not complete their practical training (450 hours up to 720 hours) after high school. This prevents students from getting their credential as Middle Level Technician and prevents them from obtaining meaningful work experience. Leaders should promote the completion of this experience as it is relevant for future technical.

Manage Challenge and Change. Principals are responsible for their school and their student´s learning and improvement. This encompasses being attentive to changes (in policy, in communities, within the education system) to adapt and change. For example, most Latino countries have moved slow towards developing strategies to make jobs competitive to respond to challenges in the new i4.0 revolution (automatization of jobs, internet of things, knowledge based economies). In this context TVET education can play an important role to introduce students to forthcoming changes.

Resource Seeking. A leader has to search for resources such as knowledge, know-how, practices, and not less relevant financial sources (e.g., of money, scholarships, or the like). This ability is not promoted as public schools are funded with government resources. Also, principals in Latino schools are not enabled to manage financial resources. However, leaders can find resources to strengthen their schools and their communities, for example, by finding opportunities within organizations and NGO´s promoting the development and improvement of learning within TVET.

Advocacy/ Commit to educational justice. Political involvement is relevant to make change happen. Teacher unions and civil organizations have advocated for the rights of students around Latin America. For example, recently students sued the government of Chile in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights due to the bias against TVET students when they take the high stakes PSU standardized test (which is designed for academic track students). Leaders can commit to help their students and the system advocating to change their conditions.

Involvement with Industry and Key Stakeholders. Leaders should be able to build meaningful relationships with important stakeholders and industries. If training does not respond to market needs, TVET training fails. Also, training opportunities can be enriched with the involvement of industries related to TVET curriculum in schools.

Manage and Promote diversity. Principals have to be able to promote the inclusion of a diverse student body. TVET students include poor and vulnerable students, overaged students, people with disabilities, migrants. All these populations deserve a high quality TVET education.

Improve conditions for TVET learning. This competence is referred to the pedagogical leadership that is stated in the Standards and competency frameworks in some Latino countries. The core of this competence is promoting TVET student learning. In order to achieve this it is important to secure conditions for effective learning (e.g., school climate, teaches trained and with proper resources, etc.). Also, it is important to promote meaningful learning experiences in TVET training. As an example, a school principal interviewed by the author of this paper stated that TVET students in his school has an Electrical Workshop in which students used a real wall of the school infrastructure to fix cables and electrical networks. This experience has helped students to realize the importance and usefulness of the skills learnt in school workshops.

Manage Human Resources. Principals in TVET schools can help promote learning by selecting the appropriate teachers (experienced and involved in the industries), developing staff and being able to assess and provide feedback regarding pedagogical aspects.

This proposal to frame TVET school leader´s competences is not overarching, as there may be many more competences required to be an effective school leader. However, it may be an example to start the conversation regarding the standards and corresponding assessment of leaders in TVET education.

Conclusion

The international research in school effectiveness agrees that 3 factors are principal to leadership strength of purpose (unity of purpose), participation and involvement of school community (to increase shared purpose and decision making) and professional authority (professional knowledge of curriculum, teaching and student outcomes). Latin America is working towards having school leaders accomplish these conditions by implementing rules and actions to improve school leader’s role. As an example, across many Latino countries Frameworks and Standards of Competency for school leadership are being implemented to define a more restricted and precise list of duties. Also, Latino countries are introducing a system for selection and performance assessments and incentives to school leaders. Latino countries are building school leadership that covers key policy issues of concern: principals focused on monitoring and supervision of the quality of schooling and teaching on the one hand and pedagogical leadership of principals and teachers on the other. That is leaders and their management teams in Latino countries are increasingly carrying out both a support role as well as a ‘monitoring-of-compliance-with-rules-and-regulations’ role.

The concept that guides the school leadership in OECD countries suggest that effective school leadership may not reside exclusively in formal positions but may instead be distributed across a number of individuals in the schools contributing to learning centered schooling, with varying governance, management, autonomy and accountability. Successful schools need effective leadership (higher order tasks designed to improve staff, student and school performance), management (routine maintenance of operations), and administration (lower order duties). Nevertheless, to develop this type of leadership in Latin-America and following the comparative analysis, a stronger articulation between standards for Administrators and evaluation mechanisms, educational regulations and management training is needed. It is also important to set a Quality Training policy that distinguishes between different moments of the directive career and the empowerment of leaders at the school level (ej. by providing more decision making responsibilities and resources to principals).

Although most of principals in Latino countries have a high level of education, 43,1% hold a bachelor degree and 20,1% master´s level, it is relevant to follow suggestions regarding school leadership training. This training must be aligned with Standards and Frameworks of Leadership and it has to be centered in developing professional skills in the leader but also construct capacities within schools (p.ej., help build truly distributed leadership and learning and professional development communities within the school). It also has to be focused on practice and adult learning principles and it is relevant if it can benefit not just the principal, for example in the double training (school leader and assistant principal).

School autonomy is not a widespread practice in the region and school principals live between a struggle of power fights that does not help their role as leaders and administrators. For example, they do not manage school resources (set teacher remuneration, define budgets, allocate resources or fund infrastructure) and neither have freedom to select, promote or exclude teacher from service (or even chose the composition of their management teams). However, they are accountable for results and outcomes even though they cannot participate in curriculum building in most countries (except Colombia where there is not a national curriculum but schools are free to tailor it). They also may not have power to redesign the organization or carry out instructional leadership. In this context Latino leaders, and particularly TVET school leaders, are far out the ideal of school leadership, in which principals set directions, develop people, redesign the organization and provide instructional leadership. This tension can be resolved with more school autonomy and by diminishing power struggles and reinforcing the importance of distributed and pedagogical focused leadership (monitoring, modelling, evaluating and providing feedback to teachers).

Finally, Australia has developed Standards and Frameworks of school leadership taking into account the needs of prospective and established principals. It is key that the standards are also linked to professional learning opportunities and some form of certification. Considering this aspect, a framework and standards for school principals in TVET education should consider the particular needs of training and mentoring for these leaders.