Introduction

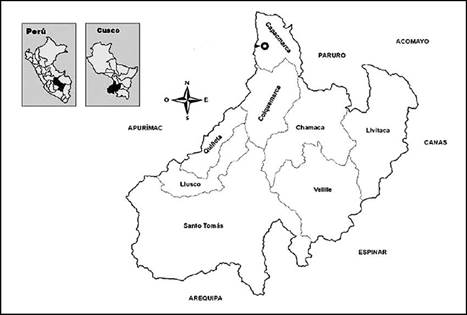

For the purposes of this study, the category of Santo Tomás city will be used, pursuant to Supreme Decree No. 022-2016-Housing, which categorizes this town as a city. Therefore, Santo Tomás city, the capital of the district of the same name and also the capital of the province of Chumbivilcas (Cusco, Peru), (Figure 1), is experiencing rapid urban growth, which has generated problems for urban and territorial management. The municipality, which is the local management entity, has deficient mechanisms for urban management in situations of territorial conflict with neighbouring peasant communities. This situation leads to urban anarchy without the municipality fulfilling its planning role in a timely and adequate manner. However, the problem is not only closely related to planning but also to existing regulations, the roles played by different social actors in territorial management, physical-legal sanitation policies, complex mechanisms of recognition or titling of communal territories, land tenure system, corruption, land trafficking, poverty, and political tension. These factors complicate and affect the proper management of territories in urban-rural contexts. In the 1980s, a radical change began, which accelerated in the 1990s with processes of privatization, deregulation, openness, and the increasing participation of economic actors (Sassen, 1995). These sociopolitical events contributed to the acceleration of rural exodus from the inhabitants of peasant communities to district capitals, particularly towards the Santo Tomás district.

Consequently, at the beginning of the nineties, socio-territorial transformations began in the villages and small towns with traditional structures that have been modified by the structural change in liberal economic relations promoted by the Fujimori government (Beraún, 2007). Consequently, the cities of Peru have experienced a 50% growth, of which 90% is informal in nature, a situation indirectly promoted by the Peruvian state through public investment in public services and infrastructure in informal settlements (Espinoza and Fort, 2020). In this scenario, land trafficking has been accelerated due to speculation in urban land, attributable to the inefficiency of legal instruments that explain this phenomenon (Pauta, 2015). However, these are not the only factors that have fuelled urban expansion, but also rural-to-urban migration due to employment opportunities, armed conflict, educational opportunities, health, and others (CEPLAN, 2023). Therefore, in this context, the peasant community surrounding the city of Santo Tomás has become inserted into the dynamics of modernity and urban influence, resulting in a destabilization of traditional lifestyle and cultural disorganization due to more individualistic behaviour and increased secularization of the peasant community in the face of urban predominance (Redfield, 1944).

Most Andean cities occupy communal lands where urban activities typically take place, which has redefined the current peasant community (Soto, 1992). Consequently, in the case of Santo Tomás, a "depeasantization" of the community members is occurring, weakening traditional values and norms of behaviour. Despite this change, as CEPLAN (2023) states, it is important for urban planning to fulfil its purpose with a future perspective, considering natural areas in plans and preserving them as heritage.

The relevant issue in the city of Santo Tomás is the urban expansion into the territory of the peasant community of Pfullpuri Puente Ccoyo Uscamarca (hereinafter referred to as Pfullpuri). This is exacerbated by a differentiated legal framework. On the one hand, there is the community with its own regulations, and on the other, the Organic Law of Municipalities, which empowers the entity to manage the urban development of the city. Each of these institutions operates under its own organizational dynamics and regulations. The city has experienced intense migration from rural communities since the 1990s due to political violence, the search for better job and business opportunities, health services, education, and other basic services offered by the city (Ortega and Mejía, 2022). This situation has generated a demand for housing, consequently leading to the city's growth into communal territory.

On the other hand, the urban problem of Santo Tomás is multifactorial, stemming from a series of subaltern interests intertwined among various socioeconomic and political actors. For some sociopolitical actors, social problems and territorial conflicts are opportunities for electoral leadership, as the impoverished peripheries of the provincial capital require support for the formalization of their "urban possessions." Consequently, influence peddling and partisan political exploitation capitalize on the needs of the population, even at the expense of exacerbating urban problems. In this scenario, the question arises: What are the mechanisms of urban management between two actors who share the same territorial space? And how is urban regulation articulated with communal territorial management and planning? The objective of this study is to analyse the mechanisms of urban management between two opposing institutions that constantly struggle to control the territory.

2. Methods

In the research process, a variety of information sources were used such as thematic bibliography, documents related to urban management, and regulatory frameworks. The methodology involved conducting semi-structured interviews with former communal directors, technicians from the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas, and representatives from informal settlements. Additionally, informal conversations were held with key social actors in the district of Santo Tomás. Simultaneously, satellite imagery was reviewed on the Google Earth platform to visualize the process of urban expansion over the last five decades.

Fieldwork has also been conducted in the study area through systematic observation of the characteristics of urbanization, facilities, public spaces, and areas deteriorated by environmental pollution. To collect information, an observation guide was used, and its application allowed for the investigation and verification of the characteristics of public spaces. Subsequently, the processing of the collected information was carried out, including organization, analysis, and interpretation of the background related to land management by the peasant community and local government.

Results and discussion

This section presents the main results regarding urban management and the role of socio-political and institutional actors in a highly dynamic scenario. Therefore, this study is organized as follows: firstly, it addresses the phenomenon of urban growth in Santo Tomás. In the second section, it discusses the territorial management carried out by the people of Pfullpuri within their community. Thirdly, it explores the city planning and management role held by the municipality; however, it cannot efficiently perform this function because the city occupies territory that does not legally belong to the urban area, although it does in practice. Finally, in the fourth section, the formalizing role fulfilled by COFOPRI with land titles is analysed, prioritizing property occupants with housing regardless of the title holder.

3.1 Urban growth in crisis

Urban-rural relationships are contemporary phenomena in the Andes, as anthropologist Matos referred to in his work "Desborde popular y crisis del Estado" (1984). According to this study, rural exodus overflowed into urban space, resulting in profound alterations in lifestyle and giving cities a new face. It is within this context that the city of Santo Tomás, experienced uncontrolled urban growth at the end of the 20th century and the early years of the present century, coinciding with the increase in economic resources transfers from the central State to local governments. However, in most urban centres of the Chumbivilcas province, two actors determine the future and form of cities. On one hand, land usufructuaries in the surroundings of towns and villages between private and collective ownership, such as peasant communities that manage according to their respective laws. On the other hand, local governments with ambiguous legal instruments, confront urban management problems, yielding scant results in a scenario of new socio-territorial and urban dynamics.

The emergence of economic spaces in the province is a new phenomenon, which is explained by the links between ancient traditions of location theory and economic geography (Fujita and Krugman, 2004). In this context, the new economic geography of Chumbivilcas places Santo Tomás as the centre of economic movements, dynamically connecting the districts of Colquemarca, Llusco, Quiñota, Chamaca, and Velille, resulting in the accelerated urbanization of the provincial capital (Figure 2). Therefore, Santo Tomás cannot be discussed in terms of the future, but rather in the present, which shows serious urban problems, generating a crisis for the adequate management of basic services for residents, regardless of the legal status of the territory it occupies.

Source: Author based on historical images from Google Earth (2023).

Figure 2: Urban growth of the city of Santo Tomás in the last half-century.

The chaotic urbanization of Santo Tomás, as well as the environmental pollution caused by siltation, eutrophication, and loss of flow in the Conde River that crosses the city, is due to the inadequate management of sewage. According Bazant (2001), due to these environmental and functional reasons, the city cannot continue to expand without control and without planning. Since the population growth of Santo Tomás affects the availability of vital resources such as water, flora, and fauna in the urban environment, and contributes to the loss of symbolic spaces that have been urbanized. In this regard, a resident of the monumental area states: "The causes of the urban chaos in Santo Tomás are the leaders of the community and the mayors of the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas, because they do not communicate. Dismemberment is not necessary because the land is already titled and registered in public records" (Luis1, personal communication, May 21, 2023). Regarding dismemberment, as the interviewee mentioned, since 2006, Law No. 28923 (Law establishing the Extraordinary Temporary Formalization and Titling Regime for Urban Properties) has empowered COFOPRI to proceed with the dismemberment and independence of urban areas within peasant communities (Etesse, 2012).

Although these socio-political actors may be responsible, the inconsistency of the legal and administrative framework was decisive in allowing this to happen. In interviews with residents occupying communal territory, the reference to "threats to land tenure" often arises. What is observed there is a degree of authoritarianism and corruption on the part of their leaders in the name of the community, who can easily exclude someone from lot possession and sell it to another occupant.

As confirmed by a resident of a housing association (APV2): "You cannot go against the community because they simply invalidate any sales agreement that has occurred and seize the land, even if you have your document" (Mario, personal communication, June 8, 2023). It is important to note that the category of "possession" is a mechanism granted by the community for effective tenure, but the corruption exerted by the majority of communal leaders is a permanent threat to land occupiers who are not community members or even community members themselves, as they can be deprived of their land through any ruse. However, the exercise of communal authority with authoritarian undertones is perceived as a strength of the organization and supposed unity, but this unity does not necessarily equate to social cohesion.

The sustained growth of the city has not been accompanied by any planning or proper territorial and urban management, but rather it has been driven by land market dynamics and the needs of peasant migrants requiring housing. Consequently, this exponential growth did not involve a process of defining zones or areas with potential for urbanization, environmental value studies of the surrounding territory, or urban planning and land use planning. As Bazant (2001) notes, it was carried out without a coherent legal basis derived from previous and current regulatory frameworks such as the Law of Sustainable Urban Development (Law No. 31313), Supreme Decree No. 022-2016, and Supreme Decree No. 012-2022-Housing. The latter decree has incorporated sustainability, urban competitiveness, and social equity approaches in the city's development (Castillo, 2021); however, it is far from being implemented in small cities in the interior of the country.

3.2. Communal land management

According to the Constitution of 1993, three types of property are classified in Peru: state, private, and communal property. Therefore, communal life is based on the territory exploited by all occupants within a particular communal jurisdiction. Until the 1990s, communities had achieved two important aspects: recognition as an institution and the legal and physical regularization of the territories they currently occupy. The General Law of Peasant Communities regulates aspects related to organization, communal territory, land tenure and use, administrative regime, communal work, economic regime, among others (Law No. 24656). Consequently, this law implies that peasant communities have autonomy in the "use of land" within their jurisdiction. Under the protection of this law, the community of Pfullpuri manages its territory based on its collective interests, although they also respond to subordinate interests of some leaders. However, with urban growth, the city of Santo Tomás is experiencing a process of urban-rural relationship with the community as a result of the liberalization of communal lands in favour of a land market without the intervention of any governing entity such as the Municipality.

With the 1979 Constitution, communal lands were inalienable, unseizable, and imprescriptible; however, the 1993 Constitution maintained only the concept of imprescriptibility. Subsequently, the "Law on Private Investment in the Development of Economic Activities in Lands of the National Territory and of Peasant and Native Communities" was approved, which in its article 11 states that "To dispose of, encumber, lease, or exercise any other act regarding communal lands in the Highlands or Jungle, the agreement of the General Assembly with the vote of no less than two-thirds of all the members of the Community shall be required" (Law No. 26505). With this law, the process of liberalization of communal lands began, leading to a process of free transfer, allowing the sale of communal lands and converting surrounding rural lands into urbanizable areas for growing cities and urban zones. However, the aforementioned law has not been properly regulated or socialized, which has fuelled confusion, uncertainty, and benefited interests outside of the communities (Baldovino, 2016). In this context, the community of Pfullpuri carried out the process of lot subdivision among its organization members, and they proceeded with the definitive alienation of the lot through its sale to third parties with the authorization of the community.

However, urbanization in communal territory did not take into account the following aspects: technical criteria, land use classification, urban planning, provision of minimum spaces for public amenities, green areas, and others. This ultimately led to the emergence of housing associations around the city in a state of anomie and self-sufficiency due to regulatory gaps and the neglect of the municipality and relevant sectors. On the other hand, spontaneous land subdivisions led to chaotic urbanization in the outskirts of Santo Tomás, which lack spaces for public amenities and services required by the city.

Returning to the nineties, as Azpur (2011) argues, the Fujimori government introduced a new scenario for peasant communities, allowing the commodification of land in the name of investment promotion. Therefore, these ceased to be assets for conservation and preservation for future generations (Gaona, 2010). Consequently, the current expression of the management of communal territories is the disorderly occupation of land, environmental pollution, deterioration of urban and rural quality of life (Figure 3), and above all, the loss of agricultural land on the city's outskirts (Glave, 2009). Consequently, in the socio-economic transformation of Santo Tomás, agricultural activities no longer prevail, but rather activities related to services required by the city. Following Ubilla's (2019) arguments, the urbanisations around Santo Tomás have a "suburban" character with precarious characteristics that are located in communal territory and mostly lack basic services and public amenities.

The peasant community manages the territory based on collective interests; therefore, the municipal authority cannot impose any urban intervention as long as the occupants are not legitimate owners of the plot they occupy. The community relies on the autonomy provided by the General Law of Peasant Communities to convert rural land into urban without taking into account any urban planning regulations regulated by the Ministry of Housing, Construction, and Sanitation and the municipality itself. The result is the tangled urban development of the provincial capital due to land speculation by the peasant community, which carries out "subdivisions" without technically considering any type of urban, territorial, or environmental planning. Gómez's proposals (2007) help understand that this situation has arisen due to market and state failures, which have redefined the scenario and the actors in territorial and urban management.

In this context, the peasant community of Pfullpuri surrounding Santo Tomás is rapidly growing without plans, through the formation of housing associations (APVs) with deficiencies in urban development. They also lack zoning plans that allow for the installation of basic services, particularly in the peripheral area, because they are the result of the community's or adjacent land users' continuous subdivisions near the city. Most of these urban developments have not complied with the regulations related to territorial conditioning processes, urban zoning, or urban development plans. Therefore, for proper land management, a regulatory and institutional framework is required for the development of peri-urban and rural cities, as well as for the peasant communities themselves (Ortega and Mejía, 2022). On the other hand, the community is managed by the Board of Directors, whose administration is guided by their own agendas and often does not adhere to collective interests (Cuadros, 2019). This situation occurs because leaders take advantage of insufficient oversight to dispose of land and frequently make decisions at their discretion.

As a result, the current city of Santo Tomás is the sum of the monumental area plus the urban area located within the communal territory of Pfullpuri. However, not all residents in this area are community members, as they have become a minority population compared to migrants who do not integrate into the communal organization (Etesse, 2012). According to references from a former leader of popular neighbourhoods in Santo Tomás, "the community does not want to register us so that we do not have communal rights, even though we live in the communal territory" (Juan, personal communication, December 11, 2022). Therefore, neighbourhoods have their own organizations and often run parallel to those of the community, but they do not have any authority within the community; in essence, neighbours on the same street, some belonging to the community and others unable to do so. Why? Community members do not want to share the benefits that would be provided, for example, by future land distributions, as if a person were to register, they would have similar benefits to the rest of the community members.

Returning to the mechanism of parcelling or subdividing for urban purposes, it has gone through the following process: first, the registered member of Pfullpuri receives the plot in perpetuity and with the possibility of alienation; consequently, this member sells the property to another member or to a buyer outside the community. In practice, sales follow the logic of private property, although when the community sells, it transfers the property as a "donation," while the members perform a "possession transfer" with the authorization of the communal authority, subject to the payment of fees. This practice has led to the emergence of a land market in the community, with active participation from the leaders, who authorize the "possession transfer" by issuing possession certificates to the transferring member, and even among non-members. However, communal authorities carry out these operations every time a transfer occurs and upon payment of fees; in other words, these rights do not expire for the community. Changes in land use have not followed any technical or planning criteria; rather, agricultural lands or enclosures have simply transitioned to developable conditions, driven by speculative interests of some land users and community leaders. In practice, these social actors have defined the characteristics of the city's current urbanization. The debate over the dismemberment of communal territory in favour of the city might seem like a favour to the municipality; however, approximately 90% of the community members own a home in the city of Santo Tomás. Consequently, the members have a direct functional, socioeconomic, and neighbouring relationship with the urban environment. Therefore, the significant investments made in all aspects in the city of Santo Tomás directly benefit the community members, who are also neighbours of the city.

Some members, particularly former leaders, still advocate for "the communal ownership," which privileges collective decision-making for territorial and resource management (Cabrera and Castro, 2023). Despite the transformation of the Pfullpuri and Santo Tomás communities, the defence and advocacy of land rights persist, a narrative that becomes a central theme in the political activities of its leaders. However, in this community, territorial management and internal organization have changed due to the individualization of land into lots, following the emergence of the land market based on Law No. 26505, also known as the "Land Law" of the Fujimori Government, which has led to the alienation of communal lands.

3.3: The role of municipal planning

Urban expansion occurred due to the inability to intervene in territories belonging to the peasant community, which has autonomy. On the other hand, the municipality has also not had timely urban management instruments, such as the Urban Development Plan (UDP); the plan it possesses is still from 2005 and remains in effect to this day, even though it may not be useful for the municipality. Additionally, the provincial municipality has not formulated territorial conditioning plans for the surrounding or peripheral areas of the urban area occupied by housing associations, urbanizations, or popular neighbourhoods, which mostly have occupants of limited resources, migrants, or in some cases, speculators.

Consequently, the issue in the city of Santo Tomás poses a challenge for urban planners and policymakers, primarily related to the provision of basic services and emerging socio-environmental conflicts in the urban environment. However, the municipality feels powerless to regulate the territory, and it is not of interest to the authorities because it generates conflicts and political wear and tear for the current administration (Haller, 2017). This situation reveals that the negligence of the current authorities regarding the formulation and implementation of urban development plans, far from resolving the issue, has rather contributed to the problem of disorderly urban growth due to disjointed physical-spatial structuring and changes in land use without considering public facilities for basic services and others.

Urban management is not new; since the 1964 regulation, there has been a preference for defining "urban development" as a mechanism for urban development management (Rendón, 2022). This means that the existence of a neighbourhood depends not only on a set of houses but also on a set of forming lots. This phenomenon was due to the concentration of migrants from different communities in the Santo Tomás district and elsewhere, generally with low incomes, who have occupied cheap land on the city's periphery, which is still communal and lacks basic services (Bazant, 2001). To improve this situation, the role of the municipality has been very passive in the face of these changes.

Following Guzmán's proposal (2005), planning is necessary as a coordinated procedure by specialists who design optimal strategies for the utilization of resources and to enable infrastructure solutions to accommodate economic, social, political, leisure, and even religious activities. Likewise, the manner of communication, such as the use of technical terminology, is important, requiring proper utilization and communication so that social actors like community members understand the scope of norms and urban development plans.

Therefore, the possibility of improving urban management requires social organization, as well as the participation of academia in research that allows for the systematization of knowledge about the various characteristics of urban development. Similarly, it requires adequate urban planning within a framework that asserts sustainable management of basic services and environmental resources. Additionally, it necessitates greater collaboration among social actors, including both community members and city residents, for the reconsideration of organizational forms and the processes of legal and physical sanitation for urban development purposes. In this context, planning must be the fundamental tool for proposing the sustainability of the city, considering social, economic, environmental, and urban aspects in a systemic process (Khalil, 2011).

Thus, as Lungo (2004) states, urban vulnerability is exacerbated by the weakness of legislation, regulatory frameworks, and institutions responsible for urban development. This is evident in the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas, which lacks sufficient legal and technical instruments to address territorial management issues on the outskirts of the city because regulations are focused on the urban environment. Consequently, it is unclear under what conditions territories that were previously non-urban cease to belong to the community and what mechanisms exist to separate a part of the peasant community so that the municipality can manage it as part of the city. The way for municipalities to exercise full control over urbanized territories is for communities to accept the separation of their territories in favour of the city, which could help with legal and physical sanitation. Since 2006, the "Law establishing the extraordinary temporary regime for the formalization and titling of urban properties" (Law No. 28923) authorizes COFOPRI to separate and establish independence for areas within populated centres that are within peasant communities. In this regard, the aforementioned law is explicit for communal territories with "informal possessions."

The mechanisms of urban land management currently may have an impact and represent an effective route for property regulation, but they are inconsistent and improvised management tools, as they were developed by municipalities without an updated cadastre to measure their respective potentialities, to prevent unplanned population growth. This problem arises from the improvisation of their administrations, which lack real technical information (Acuña, 2005). Therefore, the solution lies in defining private property and its scope as a right and the limitations of property owners towards the community. Concerning built-up areas, norms could contribute little except for improving management conditions, as Khalil (2011) suggests. In these built-up areas, what must be done is an "Urban Renewal" to properly manage urbanized territories. Meanwhile, in areas that are not built up and are located in the expansion zones of cities, strict enforcement of regulatory norms is required.

The development of urban planning norms has primarily focused on large cities, with limited impact on intermediate and small cities. Although it should be noted that the Organic Law of Municipalities has jurisdiction over urban planning, as indicated in Article 9, numeral 5, which states that it is the responsibility of the municipal council to "Approve the Urban Development Plan, the Rural Development Plan, the Zoning Scheme for urban areas, the Human Settlement Development Plan, and other specific plans based on the Territorial Development Plan" (Law No. 27972). In the same vein, Articles 79 and 89 address the organization of physical space, land use, and the purpose of urban land. However, the Municipality has not acted in a timely manner and has allowed anarchic growth of the city of Santo Tomás.

3.4: COFOPRI and its formalizing role

The Informal Property Formalization Agency (COFOPRI) was created in 1996, through Legislative Decree No. 803, and is affiliated with the Ministry of Housing, Construction, and Sanitation. The entity is the highest governing body responsible for designing and executing the comprehensive formalization of property, through the updating of land registry in Peru, thus playing a crucial role in accessing and formalizing property rights. Through the physical and legal regularization of real estate, approximately 103 hectares of land in the city of Santo Tomás, which previously belonged to the peasant community of Pfullpuri, have been incorporated. Therefore, this state policy has enabled municipal intervention for the provision of basic services and environmental management, but not for planning, as the city is already fully developed and cannot be modified further. According to the current urban cadastre of the city of Santo Tomás, three areas can be observed: the first is the historical centre (proposed by COFOPRI), the second is the area with physical and legal regularization where property holders have titles granted by the same institution, and the third area is lacking physical and legal regularization (Figure 4).

Source: Prepared based on Resolution. Chief N°113-2008-COFOPRI/OZCUS and Documents of the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas. Basic plan of the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas (2008).

Figure 4: City of Santo Tomás and its urban expansion. In accordance with Resolution. Chiefship N°113-2008-COFOPRI/OZCUS and Documents of the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas. Basic plan of the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas (2008).

The area lacking legal physical sanitation presents problems for the execution of public infrastructure projects that address the population's basic needs such as providing potable water, public sanitation, green areas, and others. Providing these services necessitates that the lands occupied by new urban developments be formalized.

With the intervention of COFOPRI and the registration of properties, possessions have been formalized, which has facilitated the incorporation of lots and houses into the commercial flow that did not exist decades ago. The titles granted by COFOPRI enhance the value of the lots and strengthen legal security to prevent a third party from appropriating the property (Cuadros, 2019). However, COFOPRI's actions legitimized, through the titles, the houses in urbanizations that were created under the logic of speculation and trafficking of communal lands without any consideration for urban planning.

Despite the fact that the urbanisations are within the communal jurisdiction, the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas has made a series of investments in public social infrastructure, such as providing water services, electricity, solid waste management, citizen security, and other services (Valle and Marín, 2000). This has facilitated urban expansion and the occupation of a considerable territorial area of the community, which changed the land use from agricultural to urban, generating tensions between the community and the municipality.

However, in this province, land registration is still perceived as unrelated to rural areas, when it is necessary to ensure land ownership and essential to maintain land tenure and its use (Cuadros, 2019). Regarding possession, in the community jurisdiction, the communal authority issues the certificate or proof of possession. However, in the urban area, it should be the municipality that certifies, as the municipal entity controls the urban cadastre, or in the best case, both authorities to improve the management of public services so that possessed lands can be formalized. In summary, the advantages of formalized property allow owners access to credit, basic services such as water and sanitation. Regarding water and sanitation, Mac Donald et al. (1998) argue that the limited coverage of drinking water services is not exclusively or fundamentally due to insufficient distribution networks, but to problems related to water sourcing and treatment. For this purpose, permission from the community is required for lots or houses within their property to be registered in public records, thus improving the quality of life of their occupants. As seen, formalizing urban property is a priority policy for both the community and the municipality.

Conclusions

The urban problem in the city of Santo Tomás is becoming increasingly complex and requires a holistic approach in urban, physical, social, environmental, economic, and other aspects. Consequently, the urban growth of Santo Tomás is in crisis, and its future is heading towards anarchy and urban degeneration with problems in all aspects that complicate city management. The described urban complexity is due to several factors that have converged to the detriment of its own inhabitants, both community members and neighbours. Thus, the former believe that it is not their city, as they constantly appeal to an ambiguous and territorial identity based on the benefits of communal jurisdiction. The factors that have contributed to this situation include gaps in the normative mechanisms of governing bodies such as the housing sector, the community, and the municipality, leading to a situation of ungovernability in territory management. Consequently, the municipality cannot fulfil its planning role in communal territory due to the legal gaps that exist, and the instruments available to the municipality are deficient or simply non-existent for urban management.

From the interviews conducted, the following emerges: according to those close to the community, they argue that the current authority of the Provincial Municipality of Chumbivilcas lacks political will to carry out urban development plans. On the other hand, municipal technicians assert that the community does not allow any planning activity to be carried out in the part of the city that occupies communal territory; furthermore, they claim that the community deliberately refuses to undergo the legal and physical formalization process of the communal territory in favour of the city where the majority, if not all, of the community members reside. Meanwhile, other social actors assert that both the municipality and the community are responsible for the chaotic growth of the city. They also accuse community leaders of being involved in corruption, as they trade land lots without considering technical or social aspects in favour of the city where they reside. Thus, the future trend of the city is unsustainable in all aspects, especially in the context of climate change.

Recommendations

To address the problems faced by the city of Santo Tomás, institutional synergies are required, along with consensus among social actors and unwavering respect for agreements. Urgent action is needed to formulate an Urban Development Plan (UDP) to prevent the city's disorderly expansion. Additionally, it would be important to define the area for urban expansion, allowing for the delineation of main roads, a ring road, and green areas. A determination of an equipment plan is necessary to improve connectivity, solid waste management, and areas for leisure. Furthermore, implementing an urban plan considering sustainable urban expansion is crucial, prioritizing from diffuse to compact development in order to manage basic services and consider areas for ecological, agricultural, and landscape protection within the city.

It is necessary to promote that the urban development plan of the city of Santo Tomás operates throughout the entire urban area, even if it encompasses communal territories, in order to foster active participation from all social actors and implement strategic operations for sustainable urban management. To achieve this, it is important for the municipality and the rural community to coordinate and promote the implementation of infrastructure, equipment, social spaces, and services. Likewise, there should be a focus on an urban model that considers public transportation services to neighbourhoods and the creation of parking areas, so that vehicles are not the primary occupants of public spaces.