Introduction

After World War I, architects gained greater prominence in the field of interior design. Although in previous decades, during the development of Art Nouveau, architects had been central figures due to the comprehensive conception of the style itself, in the 1920s, they, in collaboration with other professionals, became the creators of a new space called "modern,"1 along with a unique type of furniture suitable for this architecture. Faced with the need to equip their original architectural proposals and the circumstance of not finding suitable furniture on the market, architects became the driving force behind standardized equipment produced with new materials such as steel, which allowed for the creation of forms never seen before.

Those interiors developed in Central Europe began to spread across the continent, reaching Spain through architecture journals such as the German ones Modern Bauformen (1901-1944), Das Neue Frankfurt (1926-1933), and Innen Dekoration (1890-1944), the Dutch Wendingen (1918-1931), and the French L'Architecture Vivante (1923-1933). These media, along with books, became the most effective means of bringing the new proposals from other countries closer during the 1920s and 1930s due to their accessibility and affordability. Spanish architects, as evidenced by the testimonies of some protagonists of the time, such as Fernando García Mercadal (1981), Luis M. Feduchi (1966), Joaquín Labayen, or José Manuel Aizpúrua (Medina, 2005), were avid consumers of journals, both foreign and national, making them the main source of inspiration for Spanish architecture in the first decades of the 20th century (López Otero, 1951).

Thanks to technological advances resulting from World War I, there was an increase in graphic material in the publications of the time2. The photographic and planimetric documentation, more abundant than the written content, allowed the novelties to be conveyed regardless of language (Colomina, 1994). A significant change then occurred in the way design was communicated and consumed in its broadest sense, allowing for the copying or simulation of published spaces and furniture pieces through images. The new dissemination system adopted by foreign journals was quickly integrated into Spanish periodicals, along with their content, which experienced a significant increase in pages dedicated to interior design and furniture works over the years, both international and national. In the 1930s, this topic became recurrent in most of the journals analysed.

The contents of foreign journals, therefore, were not only a source of inspiration or consultation for professional architects but also became a resource from which Spanish publications obtained their information. Each publication filtered the information according to its own criteria, selecting the content most suitable for its editorial line and thus defining its inclination and position in the interior design landscape. Analysing a single magazine from the period can offer a partial view of what was happening at the time; however, the diversity of perspectives studied in the entirety of national periodicals provides a comprehensive picture of the reality of interior design as it was known in Spain.

Method. Through spanish architecture journals

To conduct this research, Spanish architectural periodicals published between 1925 and 1936 were consulted. For the preparation of the magazine list, Eva Hurtado Torán's text (2001), Las publicaciones periódicas de la arquitectura, España 1897-1937 was considered the main source of information. Additionally, bibliographies on general printed media were consulted, such as the book Las revistas de arquitectura (1900-1975): crónicas, manifiestos, propaganda (2012) or the article Evolución de las revistas de arquitectura y construcción en España by Juan Monjo Carrió (2019); and specific sources like the article on Nuevas Formas by Javier Martínez (2005) or the book on the magazine Arquitectura by Carlos de Sanantonio (1996), among others.

The chronological delimitation of 1925 and 1936 has been established as a result of the conducted research. Upon closely examining the contents of various journals from the interwar period, a notable increase in interest in the field of interior design can be observed starting from the year 1925, coinciding with the celebration of the Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts3. On the other hand, the choice of the closing year is based on the onset of the Spanish Civil War, which caused the interruption of editorial activities in publications.

The selection of primary research sources is delimited considering two specific aspects that can affect the dissemination and impact of their contents: language of publication and duration of edition. Journals written in Spanish have been chosen, as it is believed they reach a larger number of professionals, and publications with a minimum activity of three years, assuming they have a greater impact than those with a shorter lifespan. As a result, some significant publications of the era have been excluded from the study topic, such as D’Ici i D’Allá (1918-36, Barcelona), La Ciutat y la Casa (1925-28, Barcelona), Arquitectura i Urbanisme (1931-37, Barcelona), Re-Co: referencias de la construcción / Centro de Exposición e Información Permanente de la Construcción (1935-1936, Madrid); APAA: Revista de la Asociación profesional de Alumnos de Arquitectura (1932-1934, Madrid); ANTA: Periódico decenal de arquitectura (1932 Madrid); Las Cuatro Estaciones (1935 Madrid).

Therefore, after establishing this set of criteria to ensure greater reliability of the results, a selection of eleven journals has been made that meet the specified requirements (written in Spanish and with a minimum duration of three years), and which to varying degrees addressed issues related to interior design: La Construcción Moderna (1896, 1903-36), La Ciudad lineal (1896-1932), Arquitectura (1918-1936, 1959-…), Arquitectura Española (1925-1937), Archivo Español de Arte y Arquitectura (1923-1928), Cortijos y Rascacielos: casa de campo, arquitectura y decoración (1930-1936, 1952), A.C. Documentos de Actividad Contemporánea (1931-1937), Obras. Revista de la Construcción (1931-1936, 1942-…), Viviendas. Revista del Hogar (1932-1936), Ingar (1932-1935), and Nuevas Formas. Revista de arquitectura y decoración (1934-1937) (Figure 1).

After studying and classifying the contents4, an analysis of the data obtained has shed light on various aspects: firstly, those related to the focus of each magazine (evolution, number, and contents) regarding interior design; and secondly, those aimed at providing a broader and more comprehensive view. On one hand, this includes the panorama and evolution of spatial design in Spain from 1925 to 1936, and on the other hand, the role of architects in the development and dissemination of modern interior design and furnishings.

Results. Approaches, interests, and contents

Among the eleven selected journals, some like Ingar, La Ciudad Lineal, Arquitectura Española, and Archivo Español de Arte y Arquitectura focused on technical aspects or heritage-related topics. The few articles they published on interior design and furniture did not reflect the introduction of new forms in Spain but rather a conservative perspective on the field. On the other hand, La Construcción Moderna offered a view distinct from international trends, focusing instead on contemporary exhibition installations. The rest of the analysed journals, however, brought a new way of looking at and perceiving interior space to the public, positioning themselves in this field in diverse ways. Each of them presented a snapshot of the prevailing panorama, sometimes leading to divergent perspectives without convergence, while at other times, converging views on specific points.

Each of the journals, whether through photographs or short writings, announced their editorial inclination, implicitly emphasizing the importance given to furniture and its treatment in relation to architecture. An example is the illustrative statement from Nuevas Formas in their article "Muebles Modernos y tendencias retrospectivas," where they openly expressed their stance on interior design: "We do not associate ourselves with any trend merely by bearing the title; that's why we present here, in contrast to these interiors inspired by Spanish romanticism, others that dignify and tastefully exhibit the characteristics of modern decoration" (1934, p. 266). Similarly, Cortijos y Rascacielos published a text in 1930 stating their purpose: "to create a modern Architecture magazine that interests the general public and particularly professionals. The subject is vast. The treasure of our popular architecture; (...); the appeal of interior decoration; the new forms of Architecture and so many other issues provide us with a significant quarry to bring the Magazine to life" (1930, p. 1). Likewise, the magazine Viviendas presented a brief statement of intent that its program aimed to "highlight the most important advances being made in the world to make the home more comfortable, modern, and beautiful. To achieve this, VIVIENDAS will visually present the works of the most important architects, artists, and manufacturers worldwide" (Hurtado Torán, 2001, p. 449).

From the Exposition of Decorative Arts in Paris in 1925 until the outbreak of the Civil War, during which a large part of these journals disappeared, periodical publications adopted an increasingly interested attitude towards interior themes and their furnishings, which was unusual in earlier times. Almost all of them devoted some of their pages to studying the spaces created by architects and their spatial arrangements. Some of them, such as the journal Arquitectura, A.C. or Nuevas Formas, presented these types of projects to the public like any other architectural project. In others, like Cortijos y Rascacielos, Viviendas, or Obras, however, the publication dedicated a section exclusively to furniture and interior design, as will be seen later on.

Based on the results of this study, the following journals are examined in detail, which, thanks to their contemporary focus and prominent dedication to the interior domain, have played a significant role in the dissemination of the discipline, both among architects and, in some cases, among non-specialized groups.

Source: Authors (2024)

Figure 2 Collage of cover and first pages of articles from the journal Arquitectura.

Arquitectura5 (Figure 2), the magazine of the Official College of Architects of Madrid (COAM), published around fifty articles on interior design and its furnishings, of which eleven dealt with foreign works and nine with international and national exhibitions. After studying the content, a notable increase in interest in the subject is detected starting in 1925, the year of the Exposition of Decorative Arts in Paris. Prior to that, only five articles had been published, including texts like "Art in the Home" (Tudela de la Orden, 1920) and "The Furniture of Our Homes" (Torres Balbás, 1922), which reflected on the state of furniture and interiors, indicating an emerging concern for space design. From 1925 onwards, the magazine approached furniture works through architectural projects, presenting comprehensive works by architects who also designed the furnishings. The foreign works came from European countries, especially Germany and France. The magazine echoed the work of international architects such as Paul Linder (Lacasa, 1924), Marcel Breuer (1933), and André Lurçat (García Mercadal, 1927), and national architects such as José Manuel Aizpurua and Joaquín Labayen (1928, 1929, and 1930), Carlos Arniches and Martín Domínguez (1927 and 1933), or Luis Feduchi (1935), among others.

Although it is possible to find some isolated examples concerning furniture as an independent object, such as the article "The Art of Furniture in France," about the pieces of Pierre Chareau (García Mercadal, 1928), rarely was furniture the sole focus of the texts. Instead, its role within architecture was analysed. In addition to contributing to the dissemination of furnishing projects, this publication fostered debates on interior design through critical evaluations by various protagonists of the time, providing insights that went beyond mere descriptions. Among the texts that included contemporary theoretical reflections, we can find "The Architect Marcel Breuer" by Sigfried Giedion (1932) or "Book Review: Innen Räume" (Muguruza, 1928), which discussed modern furniture6 and its standardization. The participation of international avant-garde architects in many of its issues facilitated the spread of modern furniture in Spain.

Source: Authors (2024)

Figure 3 Collage of cover and first pages of articles from the journal Nuevas Formas.

On the other hand, Nuevas Formas. Revista de arquitectura y decoración7 (Figure 3), a publication that “stands out for its content in defence of the new spirit” (Hurtado Torán, 2001, p. 454), published 75 articles on interiors and furniture, 35 of which dealt with foreign content, primarily from Central and Eastern Europe (such as Germany, Switzerland, and Hungary). These reports generally focused on disseminating interior architecture, both domestic and recreational. Although the magazine's initial intention was to structure its content around three sections (technical works related to construction, graphic information on recent works, and art criticism articles) (1934b), it soon focused on the second section, showing a notable interest in decoration (Martínez, 2005). Nuevas Formas offered a vision of both national and international interiors through interior projects, analysis of individual pieces of furniture, and theoretical articles. Notably, critical texts and the study of furniture independently were more characteristic of national articles than foreign ones. Among them are “New Trends in Spanish Furniture” (Santa María and Feduchi, 1936/37) and “Modern Furniture and Retrospective Trends” (Santa María, 1934), which reflect on the furniture scene and present an eclectic view of the interior.

The publication placed great importance on the development of furniture, which was undergoing a clear evolution in Europe. Its interiors featured a mix of 19th-century or Art Deco pieces and furniture inspired by the avant-garde. Among the most modern national projects (mostly from the capital, though also from other cities in Spain) were the Capitol building by Feduchi and Eced (1935) and the renovation of the Aquarium café by Luis Gutiérrez Soto (1934). Internationally, it featured works by C. Reudenauer (1935), Hendrik Sendker (1935), and Paul Bry (1935b). Due to the diversity of trends it covered, Nuevas Formas could be considered the most representative publication of the situation and context of those years. The dominant eclecticism in its content offered a general view of 1930s furniture.

The journal A.C. Documentos de Actividad Contemporánea8(Figure 4), on the other hand, showcased the most 'contemporary' works, while criticizing styles from past eras. Out of around thirty articles on furniture and interiors, about ten focused on foreign works and four on exhibition spaces. Most of the published texts appear unsigned, likely due to the collective project approach characteristic of the group, which also applied to furniture design (Villanueva Fernández and García-Diego Villarías, 2014). The publication of articles on interiors was consistent throughout the magazine's lifespan (1931-37), except for the last issues.

The study of furniture was carried out in two main ways. First, through the analysis of projects in which the interior was a fundamental part, without establishing a formal dependency between the furniture and the space, such as "La joyería Roca, Barcelona" by Josep Lluis Sert (GATEPAC, 1934) or "Pequeñas casas para fin de semana" by the same architect along with Josep Torres Clavé (GATEPAC, 1935). Second, through the study of equipment; specifically, four articles focused exclusively on furniture, such as "Standard Elements of Furniture," "Standard Furniture Types GATEPAC," "School Furniture," and "Furniture for an Individual Bedroom (architects: Ben Merkelbach and Charles Jean François Karsten, Amsterdam)" (GATEPAC, 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934b).

Additionally, the magazine published several theoretical articles that reflected on interior design from a revolutionary perspective. In “Un falso concepto del mobiliario moderno” (A false concept of modern furniture). (GATEPAC, 1934c), the group emphasized the need for furniture to adapt to the life and body of its user, in contrast to styled furniture, which implied the absence of decorative elements and ensured proper functionality. The journal’s interest in interior design was not only evident through the articles appearing in its pages but also through dedicating the entire issue 19 to the evolution of interiors. This issue interspersed images of modern spaces with those that were not, marked with red lines, portraying the state of interiors at that time (GATEPAC, 1935). The principles of functionality, hygiene, and standardization were repeatedly emphasized throughout its texts, demonstrating the strong conviction of their ideas.

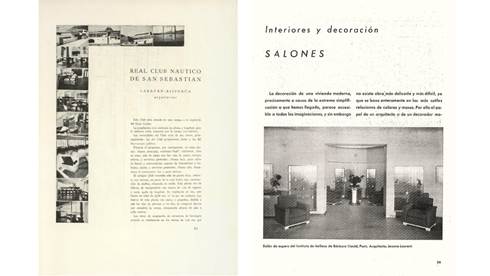

Unlike the previous journals, Obras. Revista de construcción9 (Figure 5), a publication belonging to the private company Agromán, dedicated a more or less constant section to furniture and interior spaces. Of the 47 selected articles, 18 focused on foreign works, primarily French (in some cases under the title Architectures of Today) or on key figures of the international scene (such as Adolf Loos or Walter Gropius), and 7 on exhibitions held during the period. Interestingly, out of the total articles, 14 were published within a section that experienced some variations over time. Under the titles Interiors and Decoration or Interiors, this publication presented its readers with various proposals related to spatial adaptation. This section grouped three generic articles with thematic ones such as Bedrooms, Halls, Living Rooms, Dining Rooms, Offices, Children's Rooms, Boudoirs, and Kitchens. Almost all the articles published by this magazine on interiors, except for three national ones (Bars and Cafés and Casablanca, both by Luis Gutiérrez Soto (1933, 1933b), and A Modern Store on Conde de Peñalver Avenue by Francisco Ferrer (1935), showcased spaces created in other European countries.

The articles on interiors from specific countries, such as England and France (1933b, 1933c), gained greater prominence initially, during the year 1933, while those covering the furnishings of different rooms, mentioned earlier, appeared between 1934 and 1936. During this period, foreign interiors from various origins, mostly European, were showcased through projects, sometimes accompanied by reflections on furniture and space. Many of the contents depicted domestic interiors, where the incorporation of modern furniture was generally more challenging. However, both in the Interiors and Decoration section and in other isolated articles, the magazine included images of modern spaces and tubular furniture, something uncommon in the rest of the content.

Source: Authors (2024).

Figure 6 Collage of cover and first pages of articles from Viviendas journal.

Another publication that disseminated proposals for domestic interiors being carried out in other countries was Viviendas. Revista del hogar10 (Figure 6); moreover, it offered the highest number of articles on interior and furniture. Out of the 167 selected articles, only 16 contained national proposals (five in 1932, six in 1933, three in 1934, and two in 1935); the rest showcased projects from abroad, with four focusing on exhibitions that reflected new international trends in design and housing, such as "Sol, air and house for all" from Berlin (1932d), or the "Wohnbedarf" exhibition in Stuttgart organized by the Werkbund that same year (1932e). A large part of its content came from Central Europe: primarily Germany, Austria, and France. The projects featured stood out for their adaptation to the changes occurring at the time, demanding new domestic proposals to address space scarcity or new social roles. Among the showcased projects were those of Ludwig Kozma in Budapest, to which a monographic issue was dedicated (1934c), the Luckhardt brothers and Rudolf Fránkel in Berlin, Fritz Gross in Vienna, or Pierre Chareau and Paul Bry (a French adoptee) in France.

The Spanish architects who showcased their work in the journal (interiors and furniture primarily designed ad hoc for specific spaces) shared a vision of interior design linked, to varying degrees, with new European forms. Rafael Bergamín, Fernando García Mercadal, Fernando Salvador, and Esteban de la Mora were among the protagonists. On the other hand, the magazine published at least 38 thematic articles on interior design or furniture, offering a varied selection of general aspects, spaces, or furniture pieces. In its Interiors section, it dedicated five articles to works from four specific countries: "English Interiors" (1935d and 1936), "Viennese Interiors" (1935c), "Italian Interiors" (1935), and "Norwegian Interiors" (1935b). Furthermore, it disseminated several generic articles about different materials used in furniture making, specific designs of furniture pieces, and interior spaces of the house. Among them were "Reed and Steel" (1932), "Lamps" (1932b), and "Bedrooms" (1933). The approach to interior design and furniture, due to the Central European origin of its content, leaned towards modern trends, frequently showcasing steel tube pieces and spaces devoid of ornamentation.

Source: Authors (2024).

Figure 7 Collage of cover and first pages of articles from the journal Cortijos y rascacielos.

Cortijos y Rascacielos11 (Figure 7) maintained a significant interest in interior design, especially during its early years (1930-32), when the majority of these contents were published by the magazine (14 out of 21 articles). It's particularly noteworthy how Cortijos y Rascacielos, unlike other publications, used the term "decoración" (decoration) in a high number of articles, which became a characteristic feature of passages discussing furniture and interiors in this magazine. Out of the total 21 selected articles, 12 were presented under the titles Decoración and Decoración Moderna (Modern Decoration).

The contents covered interior projects executed by both Spanish architects and decorators. It's not surprising, therefore, that fourteen articles incorporated this term into their titles. Seven of these focused on "Decoración Moderna", showcasing the direction interior design had taken during these decades.

The absence of foreign presence and, consequently, influence was a clear and consistent feature throughout the publication, which undoubtedly shaped its predominantly conservative approach. The magazine also dedicated three articles to promoting exhibitions held in Spain: two on the Ibero-American Exposition of Seville (De la Fuente, 1930; N.A., 1930-31) and one on the 1st exhibition of the professional association of decorative arts (1935e). The other seven articles focused on specific interior spaces: a bookstore (García Mercadal, 1930), an optician's shop (Muñoz Casajús, 1931), or a children's room (Poncini, 1932), among others, serving as examples.The journal covered different trends, ranging from stylistic interiors, as seen in "Decoración y romanticismo" (Prats, 1931), to steel tube furniture, such as "Muebles de tubo de acero Casa de decoración 'rolaco” (1932c).

Discussion and conclusions. Creating a culture of interior and design

After analysing the contents of the eleven journals and conducting an in-depth study of the six that provided a greater amount of documentation on the subject, some reflections can be drawn regarding the introduction of debates on interior design and their interest in Spanish publications. This also helps understand the role of the architect in the development and dissemination of modern space and furniture.

Among the ideas that can be inferred from this study, firstly, there is the diversity of positions reflected in the publications, which mirrors the characteristic eclecticism of the period12: from historical styles and art deco to modern forms. Some journals cautiously embraced the new European trends, advocating for a coexistence of styles. Other publications proposed a complete break from the past, promoting the dissemination of modern interiors in a confusing landscape marked by formal miscellany. Specifically, Cortijos y Rascacielos journal showed a somewhat moderate approach through its content, where 'style' interiors coexisted with those embracing new forms. On the other hand, the GATEPAC journal, A.C. Documentos de Actividad Contemporánea, presented information from a more avant-garde and revolutionary perspective, aligned with the modern ideas of the group; this was evident in the red lines used to express disapproval of works in 'style' or 'so-called modern' (GATEPAC, 1935). Moderating between these extremes were journals like Arquitectura, Viviendas. Revista del hogar, and Obras. Revista de construcción, which offered a more balanced view, and Nuevas Formas, with a more eclectic stance combining art deco with modern lines.

Source: Cortijos y Rascacielos (1930) 3, A.C. (1935) 19, Arquitectura (1935), Nuevas Formas (1935/36) 8.

Figure 8 Journal pages showing the eclecticism characteristic of the period.

Another relevant issue to highlight is the increased interest inferred from the rise in articles about spatial design published during the 1930s. While La Construcción Moderna, La Ciudad Lineal, Arquitectura, Arquitectura Española, and Archivo Español de Arte y Arquitectura had already begun their activities before that decade, their content, except for the case of the journal Arquitectura, did not address the interior from a contemporary perspective during that period. This could be either because they approached it through heritage, as in the case of Archivo Español de Arte y Arquitectura, or because they showed a very partial view of the subject through exhibitions, as in the case of La Construcción Moderna. The rest of the journals that emerged from 1930 onwards, such as Cortijos y Rascacielos, A.C. Documentos de Actividad Contemporánea, Obras. Revista de la Construcción, Viviendas. Revista del Hogar, and Nuevas Formas. Revista de arquitectura y decoración, published a significant number of articles on space and its equipment, stimulated by what was happening in Europe, as reflected in their content. While some of them focused on the Spanish panorama, like Cortijos y Rascacielos, others, like Viviendas, mainly disseminated foreign works.

The dissemination of articles on interior space and furniture occurred through independent pieces, interspersed with others on architecture, or through periodic sections in journals like Obras, Viviendas, and Cortijos y Rascacielos, sometimes appearing intermittently. In some cases, the articles were thematic, focusing on specific rooms, furniture, or typologies, with furnishings as the central focus. In others, however, interior design took a backseat to architecture, especially in residential and commercial or leisure spaces. The different presentation styles may have stemmed from varying levels of interest in the subject or because it was considered distinct from architecture, a viewpoint that diverged from what some modern architects of the time advocated.

Source: Architecture (1930), Works (1934) 26.

Figure 9 Magazine pages showing how interiors are offered, either as a project or as a magazine section.

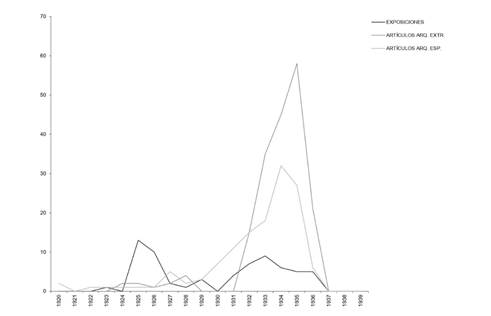

The contents of these journals were diverse. Some articles focused on significant exhibitions held worldwide, both in Spain and abroad, offering insights into furniture and interior design (Figure 9). The quantity and diversity of exhibitions between 1925 and 1936 underscored furniture's role as a symbol of modernity and progress. While each exhibition had a specific location, international participation suggested global collaboration rather than exclusive national representation. Other articles disseminated foreign news showcasing contemporary projects. Spanish journals featured work by foreign professionals of the time, highlighting interior spaces and defining their pieces. Among them were countries at the forefront of avant-garde design, like Germany, and others more traditionally aligned, such as England, straddling the line between tradition and modernity. Depending on the selection of these projects, journals positioned themselves towards either a more modern or more traditional/historicist trend. Spanish work was showcased through articles about national architects who designed interiors and made headlines in contemporary specialized publications. The featured pieces were displayed within the projects that housed them. Notable figures included Luis M. Feduchi, Fernando García Mercadal, Carlos Arniches y Martín Domínguez, Luis Gutiérrez Soto, and José Manuel Aizpurua and Joaquín Labayen, all prominently featured in multiple journals. The types of interiors and furniture varied widely, coexisting within magazine pages with both stylistic pieces and modern proposals.

Source: Authors (2024).

Figure 10 Graph of articles on exhibitions, foreign architects and Spanish architects published in Spanish architectural journals.

Finally, it is very interesting to see how in all the analysed publications there are theoretical and opinion articles about the furniture panorama, in which architects, both national and international, reflect on the needs required by the interiors of the time and the future of furniture. These types of articles, which appear in the journals of the 1930s and also in Arquitectura, which began earlier, fostered the creation of a debate about innovative interior design. On the one hand, this could influence their colleagues, and on the other hand, it could change the tastes of society at the time, since some of these publications, like Viviendas, were not only consumed by architects but there was "a type of reader interested from any perspective in the new artistic currents; contributing to spreading the new aesthetic" (Hurtado Torán, 2001, p. 450).

However, what they truly sparked was the awakening of interest in interior design and furniture, which not only transcended their time but also was the genesis of a new discipline that would develop after the Civil War: industrial design. The architect, as the author and protagonist of these journals, through articles on interior design and furniture published in the 1920s and 1930s, promoted a profound reflection on the relationship between furniture and spatial adaptation, anticipating the trends that would consolidate in Spain in the late 1950s. The architect thus became a precursor of change and a builder of a culture of interior design. Their legacy not only encompasses the creation of innovative architectural spaces but has also left an indelible mark on how we conceive and value interior design, thus contributing to enriching the design and architecture scene in Spain.