Introduction

Although the investigation of Lucio Costa’s (1902-1998) designs, works, and theories has a research framework of relevance for its disciplinary contribution, due to his leading role in the formation of modern Brazilian architecture, it still presents a limited understanding in the urban planning field. Apart from urban projects that have significant historiography, which includes the preliminary design of the Vila Operária de Monlevade1 competition for Minas Gerais, Brazil (1934), urban development plan, and the architectural design for Parque Guinle in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (1948-1954), Brasilia’s Pilot Plan, Brazil (1957), and the Barra da Tijuca’s Pilot Plan, also in Rio de Janeiro (1968), little has been systematized of Lucio Costa’s urban projects from the 1970s and 1980s. These projects include the proposal for Alagados neighborhood in Salvador, Brazil (1972), the project submitted for the competition for Abuja, the capital of Nigeria (1976), the urban configuration of a New Urban Center for São Luís, in Maranhão, Brazil (1979-1980), the urban design for a Corniche housing area, in Casablanca, Morocco (1980) and the expansion scheme for Brasilia formulated in Economical Blocks (1985). This lack of research on the urban planning of this set of proposals by Lucio Costa can be understood, in principle, as the projects were never built, except for the Economic Blocks in Brasilia. However, what can be observed is that some of these projects have generally been disregarded for research because they are preconceived as variations of Brasilia’s Pilot Plan. In the context of criticisms of the modern city model, considering the complex review of the modern movement that the academic field has experienced, rearticulating the reviews toward new ideologies, Lucio Costa has been no exception to this process of disciplinary reorganization, although such questions have not yet addressed Lucio Costa, which could lay the grounds for said absence of research.

Some urban planning factors that Lucio Costa developed are therefore not perceived, such as the elaboration of social housing, the greater attention to housing growth in urban design that led to flexibility and adaptability, non-nucleated zones, collages, and citations, deepening of nineteenth century urban planning methods, reiterating the eminently taxonomic character rooted in French rationalism and its heuristic character based on the reality of English empiricism, among other resolutions presented by the architect. Thus, examining Lucio Costa's urban planning reveals that the urbanist remained not only in theoretical dialogue with the field of research but also shows incorporations of the modern revision in his urbanism.

Lucio Costa's urban project for Alagados constituted a proposal to resolve an urban, housing, and social situation. In this light, the main approach to the systematization of this study is to a) focus on social housing in Lucio Costa's urban planning, of which there is no significant research; b) present Lucio Costa's contribution to urban planning studies, mainly about issues in the context of modern revisions; c) gather documentation about the project; and d) consider its insertion in the research field for further investigation. Therefore, the goal of the article is to analyze the urban design for the Alagados neighborhood unit, in the context of the modern movement revisionism as a proposal for the social housing problem, in order to raise discussion concerning a theoretical corpus on Lucio Costa’s urban planning.

Given the significant disciplinary changes that had been occurring since the 1950s, mainly regarding the urgent need to provide a solution to the housing issue, whether in Brazil, Latin America, or European countries with their urban centers dismantled by the war, Lucio Costa’s proposal becomes essential within the disciplinary context. The urbanist presented solutions that range from low-cost housing to social mobility and the architectural solution for the insertion of a housing model, the superblock. In an urban context with pre-existences, which was already at that point in the discussion on urbanism, it was not acceptable to neglect the place in its urban history, geography, social context, tradition, relations of belonging, culture and artistic expression. In short, in the sense of the place that Christian Norberg-Schulz (1976) takes up in the postmodern context, which in the words of Lucio Costa (2018), represents the program itself, as the basis for the development of urban proposals.

Consequently, the first section of the article offers a contextualization of revisionist approaches to urban development plans, particularly about housing clusters in superblocks, illustrating the inextricable interconnection with public infrastructures destined for residential centers. Furthermore, debates around the organicist paradigm are examined, which proposed guidelines for adaptable and flexible urban development plans, aimed at improving urban planning and the development of design methodologies able to harmoniously integrate into the pre-existing urban fabric. The second section analyzes the proposal of the superblock as a neighborhood unit in Lucio Costa's urban planning, demonstrated sometimes as a type, sometimes as a model to be reproduced, with its morphology reflected in a flexible model of an urban module, answering revisionist questions. The third section presents the dissonance raised by the superblock social housing policy based on the utopian thinking of the legal, economic, and social system by overcoming the traditional urban design that modifies the principle of private property. This dissonance between the superblock social housing policy and the financial policy of real estate interests points to the factor that did not allow Lucio Costa's proposal to be carried out. Finally, we outline our conclusions based on the evaluation of the contributions of revisionist debates on modernity in Lucio Costa's urban planning practice, supporting the premise that, if Lucio Costa's proposal had been adequately contemplated, it is plausible to assume that the current context of Alagados would have experienced substantial improvements.

Methods

In this way, the article presents the Alagados project as part of ongoing Ph.D. thesis research that is being developed on Lucio Costa's urbanism in the context of the review of the modern. The research, which also encompasses a historiographical approach, developed within architectural theory, focuses on a design perspective. The study, which was established as a review of architect Lucio Costa's proposal, adopted a methodology for collecting and examining documentation, plans, and works, for the analysis of the proposal in Lucio Costa's urban planning and in the context of the review, which required a bibliographic review.

Lucio Costa (2018) presents the main documentation found about the Alagados project in his work “Registro de uma vivência2”. In research carried out on the urbanist's collection, currently at Casa da Arquitectura in Matosinhos, Portugal, there is only one image, not mentioned in the aforementioned reference, that the urban planner presents a study on the proposal, with no further information added.

The literature review carried out for the main research was based on primary documentary sources from the architect himself, sources from referential authors, and particular sources that stood out in the modern review. For this specific research, no sources have been found, other than those by the architect, which provide any in-depth information on the project for Alagados. The main related sources, which are limited to the architect's work in general and reviews of the modern movement, made it possible to establish verifications on the study subject and compare conclusions.

The objective of analyzing the Alagados project, covered in this article, includes the possibility of deepening and initiating an exploratory approach to studies on Lucio Costa's urban planning. Because, it was through this architect's projects and writings that Brazilian architecture, in addition to gaining maturity, improved essential issues within the disciplinary scope.

The superblock under critical review of the modern movement

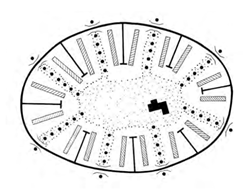

The proposal of the North American urban planner Clarence Perry’s (1872-1944) on neighborhood unity through urban design aimed, in the 1920s, to promote an urban unit that fostered community relations. Similarly, the concept of housing grouped into neighborhood units, outlined by Radburn (1928) in the North American scenario of New Jersey, developed by Clarence Stein (1882-1975) and Henry Wright (1878-1936), also advocated strict separation between vehicle and pedestrian traffic, in addition to seeking a sectoral approach to foster community dynamics and facilitate the provision of the corresponding social facilities (Figure 1). Subsequently, the Charter of Athens (1993 [1933]) reiterated the idea of a typological proposal, as the “initial nucleus of urbanism is a housing unit (a house) and its insertion into a group forming a housing unit of appropriate proportions” (Le Corbusier, 1993, p. 143) and further determined that “it is from this housing unit that the relationships between housing, workplaces and facilities dedicated to leisure time will be established in urban space” (Le Corbusier, 1993, p. 143). In this way, the fundamental configuration of neighborhood units was delineated by the organization of a population grouping of three to four thousand inhabitants close to the primary school and kindergarten, “designed so that no child needs to walk more than half a mile to school, preferably without ever having to cross a major traffic artery” (Mumford, 2000, p. 307-308).

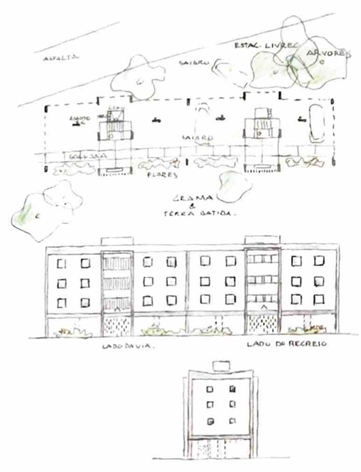

The principle of neighborhood units would draw on the principle of self-sufficiency in having their own facilities and commerce. This characteristic generated postmodern criticism regarding the isolation of neighborhood units from each other and the general dynamics of the city. Kevin Lynch (1972, p. 320) put it this way, saying that “the majority of residents are not socially organized in such units, their lives do not center around primary school, nor would they like to be confined in such areas, with all the implications of local isolation and lack of choice”. Nevertheless, Lucio Costa, in Brasilia’s Pilot Plan, shaped the neighborhood unit into a set of four superblocks, which can amount to up to twelve thousand inhabitants, and share with other neighborhood units their respective commerce, supermarket, neighborhood club, post office, police station, library and service stations, in addition to larger facilities, such as a cinema, shopping arcades and sports courts, as Marcílio Ferreira and Matheus Gorovitz (2020) listed, responding to the problem of urban isolation by designing the insertion of the housing cell in a growing set of urban scales. For the Alagados project, Lucio Costa designed models for urban facilities, such as the cinema auditorium, the chapel, the daycare center, and the primary school (Figure 2).

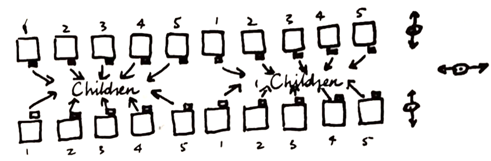

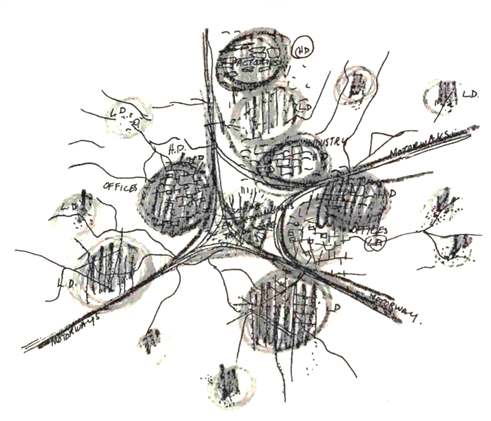

Hans Scharoun and Alison and Peter Smithson undertook an analysis concerning an "organicist" paradigm, which was characterized by harmonious adaptation to pre-existing elements of the urban structure, including through the implementation of a children's association model related to the public space of roads (Figure 3). For Alison and Peter Smithson, “the search for groupings answering patterns of association, patterns of movement; able to give identity, responsive to place, to topography, to local climate” (Smithson and Smithson, 2005, p. 19), cannot be adapted to other locations, as they are adaptable to building types that have their own specific relationship with motorized traffic (Figure 4). The housing cluster model that Lucio Costa defined differs from the creation of a model for the “cluster” concept. Differently, the Alagados superblock model is later reproduced in a proposal for the Nigerian capital and the expansion of Brasilia (Figure 7). This issue demonstrated that Lucio Costa's procedure of taking advantage of the Alagados superblock model for the Brasilia expansion proposal did not seem to take into account the primary issues for the Smithsons' “cluster” concept “responsive to the place, to the topography to the local climate” (Smithson and Smithson, 2005, p. 20). This occurs because the architectural dimension also guarantees its quality for other applied contexts, developed in the Brazilian modern repertoire as adaptable, up to a certain limit, arising from the specific flexibility of the pilotis, to the site, to climatic variations, due to the constructive elements of climate regulation, such as cobogós3, brises soleil4, windows, as currently occurs in Brasilia, both in the Cruzeiro Novo neighborhood and in the Economic Blocks.

Source: Smithson and Smithson, 2005.

Figure 3 Diagram of child association pattern in a street, Alison and Peter Smithson, 1949-1950.

Source: Smithson and Smithson, 2005.

Figure 4 Diagram showing population clusters, each working or living in type of buildings that have their appropriate relation to motor traffic, Alison and Peter Smithson, 1955

Following Barra da Tijuca’s Pilot Plan, Lucio Costa reviewed urban planning in his projects. Criticism was levied by Bruno Zevi (2012), both on Brasilia’s Pilot Plan and on the participants of CIAM VII (1949) 5. In Barra da Tijuca’s Pilot Plan, Lucio Costa designed areas for urban growth integrated in the general plan. In the design for Alagados, Lucio Costa proposed a housing unit for expansion. Therefore, it was again proposed for the Brasilia expansion project, where it was actually carried out. This question about planning takes on importance at the disciplinary level as the degree of destruction of the old to build the new was also observed. This issue is revisionist in the sense that the Charter of Athens (1993) did not protect this aspect as part of the doctrine. According to the descriptive document of the urban proposal for Alagados, Lucio Costa, already firmly convinced about his planning intentions, argued that “when it comes to planning the future of a living urban organism, whose roots go deep into history and ecology, one should not want to encompass the space and time with the establishment, a priori, of structures that are too rigid, destined to contain a body that must conform and grow under the action of variable constraints, some unpredictable” and concludes that “one cannot intend to cage the future” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 334).

Thus, Lucio Costa reviewed the ideas of flexibility and adaptability, typical of the postmodern context, in the spectrum of criticisms of modern urbanism, which Rem Koolhaas (1978) also discussed in “Delirious New York”. In this work, Koolhaas described New York as an architectural “battlefield” between forces and interests that fight against one other, adapt and overlap, as in a “chaotic machine”, with “hyper density”, a mix of uses and efficiency of urban space prevailing, as a specific characteristic of Manhattan, allowing it to transform over time. New York's flexibility lies mainly in its constant construction and demolition action that fosters heterogeneity, flexibility, overlapping, collage, and citation. It is also particularly a study on real estate speculation and the media in the field of transformations in the territory.

Jane Jacobs (2001, [1961]), on the construction of neighborhoods in “Death and Life of Big Cities”, pointed out the ability of cities to adjust to social, economic, and cultural changes, which can guarantee a safe, democratic, and fair organism. Within the critique of modern models, Charles Jencks (1985) defended the flexibility of urban spaces in the face of modernist approaches, thus allowing possible approaches within the scope of the diversity of styles and historical references and the recognition that the complex system of cities includes social changes, economic and cultural in constant transformation. Jencks (1985)thus discussed rigid plans as part of modern failures and as such issues within the scope of the postmodern avant-garde and its relationship with cities. The aforementioned authors, comprising the Anglo-American axis, were carrying out reviews on North American cities, which were examples of a review of the modern model applied to develop planning and defend the urban landscape movement, which evolves from community participation related to vernacular design, systematic empiricism, historical preservation, the exploration of historical eclecticism, the development of neo-traditional urbanism and relations with peripheral cities (Ellin, 1999 [1996]).

In Lucio Costa's urban planning, flexibility in urban design, in the sense of being able to accommodate future changes, without imperatively overlapping the existing urban layer, systematized in urban design, began in Barra da Tijuca’s Pilot Plan (1968). Here, it was inserted in the central areas, zones for programmed growth, from the sectoral scale to the urban scale. From this moment onward, it was a constant feature in the new urban proposals he designed, reflecting the critical discussion about the rigid models of modern urban designs proposed in the 1920s and 1930s. This dimension of considering the complexity of the urban fabric, in its sense of palimpsest, which, in the view of Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter (1978), allows bricolage as a methodology of urban spatial conformation, exalts collage and citation as legitimate methods of design. From another perspective, current investigations, such as the research by Guilherme Lassance et al. (2021), about the “Post-compact City”, demonstrate a new vision based on Lucio Costa’s urban planning, when considering design strategies from Brasília, in the relationship between its built materiality and marking, earthworks and landscaping operations, point to the capacity for possible interventions in the production of contemporary urban space in the Brazilian capital.

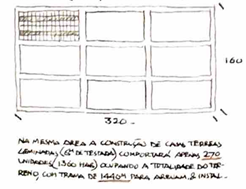

The project for Alagados, due to its sectoral scale, opposes the idea of a “total design”, which James Holston (2004) identifies as one of the ways of designing and planning that occurred for Brasilia’s Pilot Plan. Holston (2004, p. 167) identified that the total modernist design consisted of the attempt to “overcome the contingency of modern experience by fixing the present in a fully conceived plan, based on an imagined future”. And he further observed that this type of design “is maintained by the completeness of the plans themselves, which have a static character, like a set of instructions”. Holston (2004, p. 167) also identified that the second way of designing, “contingency design”, “improvises and experiments as a means of dealing with the uncertainty of current conditions” and that “works with plans that are always partial” enable means for a future alternative, based on “imperfect knowledge, incomplete control and lack of resources, which incorporates conflicts and contradictions as constituent elements” that will present a “significant insurgent aspect”. For Brasilia, Holston illustrated the contingency project with examples about the construction worker as a bricoleur, due to his self-imposed self-construction; about the contrast between the regulated construction zone and the market town; and the development of illegal establishments as a reaction to the government's planned occupation. In the case of Alagados, it is not possible to identify the total design due to the restricted elaboration in the superblock, which ended up planning only the community housing unit, that would still not necessarily constitute a housing area. And, as pointed out by Lucio Costa, the contingency design, due not only to the local condition but also the review of the total modern project, is applied more appropriately. Holston's brief discussion on the incorporation of the conflicts and contradictions of the place by urbanism, in order to promote urbanization and re-urbanization, is a reflection of discussions on the review of the modern since the late 1950s and the 1960s when Jacobs sized up the conditions for the foundations of urban planning where the social behavior of the urban population, economic performance, the dichotomy between decay and vitality and housing practices, human and vehicle traffic across large areas and internal areas must be considered. However, such determination of a restricted project for a neighborhood unit does not mean, in the experience of Brasilia’s Pilot Plan and Economic Blocks, a low land occupation. According to Lucio Costa, a study carried out for Alagados proves that the superblock model has a higher rate of occupation by inhabitants per area than the standard type of urban block (Figure 5).

Alagados: a superblock model for social housing as a module for urban planning

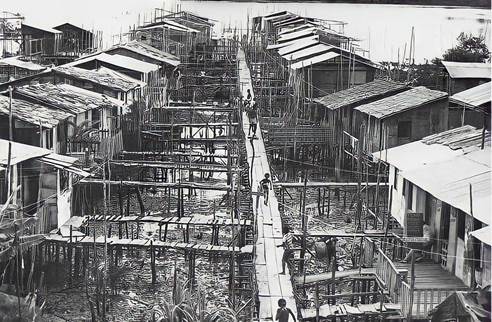

The Alagados neighborhood was a group of self-built houses on dry land and over the tidal area that began to develop in the 1940s in the capital of the State of Bahia, in Salvador, Brazil. The cluster of stilt houses, wooden houses with precarious architectural, urban, and social structures over the tidal area, where the main means of connection was through wooden bridges, was one of the typologies that made up the neighborhood's housing repertoire. It thus expressed, through its name “Alagados”, meaning flooded, the architectural, urban and geographic conditions of the individuals and territory (Figure 6). In 1961, the architect Diógenes Rebouças was hired to prepare a preliminary design for the Recovery of Alagados (Gordilho Souza apud Nunes, 2000). At that time, Diógenes Rebouças had just taken over the coordination of Salvador City Urban Planning Office (EPUCS). In 1967, a series of procedures began to intervene in the region and provide a definitive urban and social solution. The Alagados Recovery Plan (1967) was thus designed for a population of approximately 78 thousand people (Santos, 2005). In 1969, the Executive Commission for the Alagados Recovery Plan (CEPRAL) was created, through the State of Bahia’s government to monitor the Plan’s implementation. Everything points to the fact that Lucio Costa made the urban proposal for Alagados when state interventions began in the region, and when CEPRAL was defining a new zoning for the neighborhood. The date of the project, 1972, thus coincides with the creation of the Study Group for Alagados of Bahia (GEPAB) through an agreement with the National Housing Bank (BNH), to replace and incorporate CEPRAL and provide efficient continuity for the implementation of the Alagados Urban Plan. According to Lucio Costa, “the recommendations made, in 1971, to the Municipality of Salvador at the request of its honorable Mayor Dr Clariston Andrade [...]”6 indicates that there were negotiations on the project, however, there is not enough documentation available to define the limits of the agreement7.

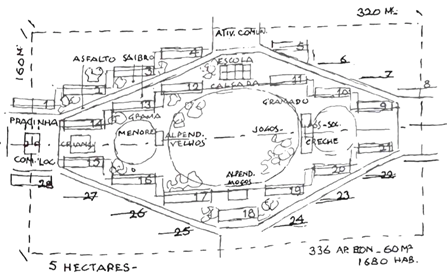

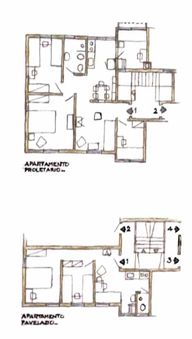

Concerning the size of housing, Lucio Costa developed the superblock as a systematic process in his urban planning. It is a proposal for a multi-family housing cluster composed of housing in apartment blocks on stilts, varying between blocks of three floors, intended for proletarian housing, and six floors, intended for middle and upper classes. It also included public facilities of educational nature, primary and secondary schools, and daycare centers; public facilities for leisure purposes, separate areas for recreation, rest, clubs, cinema-auditorium, for community use, such as a church and community center; a circulation system for vehicles and pedestrians; and a tree-planting and landscaping system, both for the spatial conformation of the superblock and for the adequacy and characterization of the interior spaces.

In Lucio Costa's urban planning, the superblock was a module driving urban composition, prioritizing the function of determining the structure of the city and composing its scale. It occurred as a foreshadow in the Parque Guinle’s urban development plan; as a theoretical conformation and driving module in Brasilia’s Pilot Plan; in Alagados social housing proposal; and was also presented with polygonal variations in the project for Nigeria’s capital. In addition, it was presented in a circular format for spatial adaptation in a site bordered by rivers in the New Urban Center of São Luís; in a varied composition in the Corniche project; and the Alagados proposal was reused for social housing for the Brasilia Economic Blocks proposal. The model presented for Alagados had already been, in a reduced form without defined urban facilities, applied and built in the satellite city of Brasilia, in Cruzeiro Novo (1959), also as a proposal for social housing.

Thus, within Lucio Costa's urban repertoire, the type of superblock varied to respond to the program, correspond to the urban scale, and provide the appropriate solution for the program. Lucio Costa was concerned with the scale for the composition that would give the character to the urbs when resizing the monumental scale in Brasilia’s Pilot Plan, also resizing the housing unit, creating a new dimension for the urban fabric, in addition to a new dimension for the block of 280 meters by 280 meters and a population of 2,500 to 3,000 people, which ended up being called “superblock” (Figure 7). According to Lucio Costa, regarding the size, the superblock was formulated as a response to the problem of the monumentality of the civic center of Brasilia’s Pilot Plan, where it was necessary to create a housing block proportional to the monumental size (Costa, 2018). This concern for proportionality about the urban complex, when considering its entirety, had already been a guideline for his urban planning when he prepared his first urban planning design, the Vila Operária de Monlevade project. Lucio Costa argues that “the houses were grouped two by two [...] both for economic reasons, obviously, as well as for plastic reasons because if they were loose from each other, too small as they are, they could appear mean in the landscape” (Costa, 2018 [1934], p. 54).

Source: Costa, L. (2018).

Figure 7. Superblock and neighborhood unit design for Brasilia’s Pilot Plan, 1957

Quatremère de Quincy's definition of model and type, which serves as a theoretical basis for Giulio Carlo Argan's discussion on the concept of architectural typology, determines that

the model, understood according to the practical execution of art, is an object that must be repeated as it is; the type is, on the contrary, an object according to which anyone can conceive works that will not resemble each other in any way (Quincy apud Argan, 2001, p. 66).

This definition is important for verification in Lucio Costa's urban planning, given that the proposals for neighborhood units end up being differentiated between type and model, depending on his urban planning proposal. For Brasilia's Pilot Plan, Lucio Costa designed a type of superblock and a type of neighborhood unit, which guaranteed a diversity of urban and architectural solutions for the city. To this end, in Brasilia’s Pilot Plan, Lucio Costa defined the concept of the type of superblocks that must obey two general principles, being criteria that still define Brasilia's urban planning today: “maximum uniform size, perhaps six floors and pilotis, and separation of vehicle traffic from pedestrian traffic, especially access to the primary school and existing amenities within each block” (Costa, 2018 [1957], p. 292). This also occurred at the preliminary project level in the definition of the type for the proposal for Nigeria’s capital and in the New Urban Center of São Luís. For the Corniche project, Lucio Costa defined the model of the neighborhood unit and superblock. For the Alagados proposal, Lucio Costa defined a superblock model, meaning a proposal that on a sectoral scale did not permit variations, however, it should behave like a flexible module that shaped urban space. In the case of Alagados, Lucio Costa indicated that it should be implemented strategically as a module in the neighborhood where people already lived, in areas that should be filled in, that is, in new areas that would follow the same principle of territorial domination already in process of development in the region. This also demonstrated a contrary position that was common in housing policies in Brazil of relocating people to isolated and distant areas when they were in precarious social and urban conditions, as demonstrated by Nabil Bonduki (1996, cited in Guerra, 2010).

Hence, the proposed housing unit for Alagados is expressed in conciliation with perimeter housing on pilotis with an internal courtyard with self-supporting parallel sheets - as opposed to the block as a private building block - where the general form is configured by the limits of the roads in a diamond shape and the outer shape in a rectangle, which is characterized independently of the function, forming a nuclear grouping system (Figure 8). The autonomy of space, in Lucio Costa’s housing unit, which occurs with a formal priority over function, varying from square, diamond-shaped, circular and rectangular shapes, with variations in the layout of buildings and spaces, was a development over the superblock that was being designed by conforming the urban space into regular meshes, or organic meshes. Lightness, a striking formal characteristic of Brazilian architecture, which in the case of the creation of urban space occurs through the balance between the built mass and empty spaces, ended up differentiating the superblock models proposed by Lucio Costa, such as the Mietkasernen typologies developed in the 1920s, where the weight, the closure of the court, high density and the internal labyrinth define a configuration of another complexity. The predominant diamond shape is a variation of axis symmetry. Formal restraint is evident, objet-type8 isolated from each other.

In the social dimension, for Brasilia, Lucio Costa clarified that “what was wanted was to form a Neighborhood Unit out of every four superblocks, in which at least three social levels coexist” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 319). For Alagados, where it sought to respond to the housing problem of the less favored proletarian class, a single superblock was defined, with three-story buildings and two apartment models (Figure 9).

In the urban dimension, inspired by the poetry of Luís Vaz de Camões, in sonnet 92 (1595), which states that “Times change, desires change, being changes, trust changes, the whole world is made of changes, always taking on new qualities” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 333), Lucio Costa announced the design premise, in the context of the Alagados project, that space should not be built with rigid structures so as to allow the action of variable and unpredictable constraints to be added as part of the development of urban space. Therefore, the proposal for Alagados was spatial planning reduced to the neighborhood unit model, which, unlike Brasilia’s Pilot Plan, where Lucio Costa consolidated a type of neighborhood unit composed of four superblocks and a set of public facilities, was composed only of one superblock unit, and the establishment of fundamental criteria, “which, to a certain extent, will serve to guide the future configuration of the city” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 333). Such a conception allows a flexible urban formulation due to its dimensions and can be considered as part of the solutions to the critique of the ideology of modern urbanism, which Manfredo Tafuri (1986) expressed regarding contextualization in the post-war period when is no longer acceptable to claim definitive propositions for the definitions of space and ways of living, especially when it comes to a territorial and urban scale. Also, as a constructive strategy to ensure continued local urbanization.

In this sense, Lucio Costa defined his urban planning as a theoretical and typological proposition of an autonomous housing unit model, to promote the dynamics of a community. This is due to the presence of different uses, commerce, housing, leisure, services, and aggregation by age, interest, and activities. Furthermore, the proposal for Alagados is a housing unit model for social housing in a rectangle of 320 meters by 160 meters, a diamond layout with a well-marked center like a courtyard, with the school, daycare center, games area, porches for collective activities separated by age, squares, empty spaces, and a tree-planting system. The superblock’s morphology stems from the model already developed as proposed by Lucio Costa for Parque Guinle, where its morphology was defined by its implementation within a park, reproducing the ideas of the garden city. This configuration recovered the square as a public space for non-programmed activities, supporting the value of the isolated building that enhances its individuality, giving the inhabitant a relationship of belonging to the building, however, contextualized in a community space, inserted in a continuous network and committed to the pedestrian scale.

Regarding the establishment of fundamental criteria, for Lucio Costa, Alagados, “whose roots go deep into history and ecology” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 333), due to the mode of occupation, should, firstly, prevent the “real estate sub-industry” from making additions to what exists onsite so as to ensure that urban space, due to its very way of being, rejects the real estate industry defining urbanity driven by its business. Lucio Costa explained that for this to happen, whilst still guaranteeing the possibilities for change typical of a “living urban organism” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 333), fundamental guidelines propositions must be attributed so that these comprise the main master plan to ensure urban spaces adaptable to social and cultural conjectures. Furthermore, Lucio Costa's housing unit, which would become self-sufficient, would include “housing complements”, such as public facilities, the cinema-auditorium, the chapel, the daycare center, the primary school, the secondary school, the porch for young people's activities, homes for the elderly, and a little building for small workshops, so that the community, in addition to having their properly guaranteed right to public facilities, would benefit from territorial planning based on community relations certified by public facilities. This configuration would extend from the sectoral scale of the superblock to an urban scale as it presents greater heterogeneity in the coexistence of different uses of the housing unit.

Lucio Costa proposed, in addition to curbing the real estate sub-industry, a sociological survey of families to direct them to the most appropriate housing type according to their family pattern. Starting the architectural design process for social housing through a sociological survey of families, reflected the discussions that took place from the 1960s onwards, that is, by this time in a revisionist context, for the adaptation of urban planning from a democratic perspective. Such discussions are exemplary in the contributions of Paul-Henry Chombart de Lauwe (1960), who, in addition to the sociological survey, developed processes of user participation. In Parque Guinle, designed for the “high bourgeoisie”, the presence of balconies, originating from the Portuguese-Brazilian rural bourgeois house, prevailed. On the other hand, in the Alagados’ smaller typology, Lucio Costa designed for families where “the readjustment would prove more difficult” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 335), which seems to mean, for families that do not conform to regulations, “the living and working areas are confused” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 335), as in the architectural pattern of Brazilian shantytowns (favelas).

Thus, Lucio Costa seems to create a spatial model rooted in the architectural culture of the considered social-economic class. This vision incorporates the idea of the “minimal home” for people, which is reflected in the construction of the community zone, where the grouping gives a sense of unity to the place and is linked to ways of being (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 333). In addition, it is linked to the extensive post-modern debate, which focused on the expansion of disciplinary boundaries, where notes from social sciences, behavioral psychological sciences, and anthropological sciences began to be considered. This historic period began to consider not only population numbers, but also their specificities of family, composition, age, social classes, work, and which should consequently be expressed in the type of housing, in the conformation of the sectoral scale, in the participation of users in urban planning, to respond not only to architectural issues but participate in the formation of a sense of community.

Lucio Costa designed the housing unit, the set of buildings, the housing itself, the recreation and leisure facilities, and the school, materializing architecture to guarantee human rights, as the urbanist lists: “Health, social assistance, education. Kids and adults. Literacy, teaching skills, assigning tasks; treating them as people and not ‘sub-persons’. Give each person and each family what everyone should have - decent housing - and make sure they know how to use and preserve it” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 334), and the possibility of upgrading the space gradually, replacing or adding, such a grouping model.

In this way, the development of a neighborhood unit model with a scale capable of adapting to different urban contexts would be possible. A methodology of shaping urban space to the extent possible, thus reducing the planning of the housing zone indifferent to the heart of the city, leaving monumentalist intentions aside. This model of housing cluster that Lucio Costa proposed for Alagados, as a unit that can be added wherever necessary, that is, in a city already born, alive, and undergoing transformation, seems to want to guarantee the aspects of urban sociology. When proposing the superblock model for Alagados, as it is for Brasilia, it would define the ground as public, due to the buildings on stilts and the management of urban land, where the buyer of the housing unit only acquires the projection, without taking control of the ground floor, the underlying land, so as to guarantee the free movement of people, the continuity of urban space, and public administration’s control of public space, ensuring fixed areas for small and larger vegetation, areas for public facilities, and empty areas to enable an atmosphere of urban space, thus assuring proper urban quality (Figure 10).

Dissonance between the superblock social housing policy and the financial policy of real estate interest

It was in the project for Alagados that Lucio Costa directly developed his proposition on social housing. Lucio Costa forged the proposal in light of the awareness of social responsibility where he highlights that “passive acceptance by administrations and the general public of the existence and continuous growth of this urban aberration, where man normally lives with rot [...]”, is the “reason why it seemed imperative to have a detailed proposition able not only to contribute to the development of the problem but also to enable a ready and adequate solution” (Costa, 2018 [1972], p. 334). The superblock, thus sought to respond to the problems of housing, urban conformation, to the necessary flexibility without abstaining from urban prerogatives, access to urban facilities, social mobility, and its community environment. Lucio Costa dimensioned the problem of housing, in the context of “massification” in the light of a technological era in which it is “possible to provide all people with decent living conditions” (Costa, 2018, p. 310). Lucio Costa scaled this issue to a disciplinary vision: “the home of the common man must be the symbolic monument of our time, just as the tomb, monasteries, castles, and palaces were in other times” (Costa, 2018, p. 310).

Using the research by Candice Tomé (2009) on the Brasilia Economic Blocks (Figure 11) that reproduce the project proposed for Alagados, it is observed that user satisfaction is positive, demonstrating that the most frequent change among residents is about repositioning the interior of the apartment rooms to adapt the space better to suit the family, the closure of free pilotis by bars due to cumbersome public security and to delimit private parking areas. Regarding the supply of social housing, Tomé's research showed that this is still the case for the lower social classes located in a place with a circulation route that easily integrates into Brasilia’s Pilot Plan.

On the other hand, the property system of the superblock, based on the utopian thinking of social reformers from the beginning of the 19th century, the ideals of the garden city, and the urban conformation of the linear city by Arturo Soria y Mata (Carpitero, 1998), brings with it the overcoming of traditional urban design and a change in the economic, legal and social system of the principle of private land ownership that defined the spatial organization in lots and blocks. This system proposed by Lucio Costa, currently built in Brasilia, has not found political alignment with an interest in promoting social housing conditional based on real estate financial policy.

From the project that Lucio Costa prepared for Alagados, nothing has been considered to resolve the local problem. According to Janio Santos (2005, p. 93), “the goal of the State's interventions was to insert residents into the capitalist real estate logic and plan popular housing as a way of raising resources”, which explains the political rationale behind the project construction. Lucio Costa was not aligned with public policies in the urban land production process. What Santos demonstrated was that instead of prioritizing the housing issue itself, the program focused on the inclusion of Alagados’ population in the housing financial policy, which was not positive in resolving the housing problem. Santos also demonstrated that the result of the State's interventions, in the various stages of the urban development plan, was reduced to providing lots for residents and providing them with precarious construction materials so that the inhabitants could build their own homes.

Conclusion

Currently, despite state interventions, the Alagados neighborhood persists in its inability to adequately accommodate the population, remaining characterized by precarious housing occupation.

When considering the effectiveness of the project for the urban expansion of Brasilia, as discussed by Tomé (2009), the superblock model designed by Lucio Costa for Alagados was committed to the conception of an urban environment aimed at the social rehabilitation of the resident community. Lucio Costa's defense of safeguarding against the exacerbated influence of the real estate industry, outlined as a priority measure for urban restructuring, currently stands out as a preponderant factor in obtaining unfavorable results in the urban context of Alagados, due to the prevalence of marketing logic in the planning of social housing.

The housing policy guidelines at the time established the position that they were not interested in partial solutions since State participation would only make it possible to define and implement an overall solution, while progressively capable of guaranteeing rapid and flexible execution (Bahia, GEPAB, 1973). This orientation, in addition to demonstrating a contradictory aspect to Lucio Costa's flexible proposal, clashed with planning perspectives for living urban organisms that are conditioned by unpredictable variables.

The study of the urban proposal for Alagados allows us to conclude that Lucio Costa's urban planning was sometimes modified in response to the formulated questions by the revisions that took place over the second half of the 20th century, and was sometimes preserved in the modern rationalist doctrine. Furthermore, it allows us to understand that Lucio Costa’s proposal for social housing, in addition to a project adjusted to the program, must be accompanied by planning guidelines to guarantee the due role of the State in regulating urban land to ensure that social housing is carried out and also to promote social mobility, that is, depart from the condition of “flooded” to live in a decent house, which unfortunately did not happen in Alagados. Based on the positive evaluation of the Urban Well-Being Index (IBEU) applied to the Brasilia Pilot Plan and the favorable analysis of the Brasilia Economic Blocks, which mirrors the project designed for Alagados, it is possible to conjecture that, if Lucio Costa’s original proposal had been fully adopted, the social, economic and urban results would have been manifest in a more significant and favorable way within the current urban context of the Alagados neighborhood.

Recommendations

This research points out that, apart from Lucio Costa's urban planning projects, his architectural projects (Barreto, 2023) also lack research when considering the revisions that the modern movement has undergone. In addition to the relationship between modernity and tradition that the architect established in his work, other occurrences can also be observed that were being developed and that establish direct dialogues with the discussions that took place after the 1950s. To this end, new investigations could shed light on a field in which historiography related to modern Brazilian architecture is still limited.