Introduction

The importance of involving citizens in public policies

Citizens demand that, in addition to receiving quality public services, local governments should be receptive to their proposals in defense of general interest. Civil society increasingly demands greater transparency and participation in public management and calls for the creation of instruments that bring citizens closer to the centers of political decision-making, as evidenced by the continuous presence of the topic in the media (Costa, 2019; Del Campo, 2016; Pacheco, 2021; Pérez-Colomé, 2018; Valiente, 2021; Vidal, 2021).

Citizen participation refers to a set of mechanisms that allow citizens to contribute to any phase of the public decision-making process, acquiring effective decision-making power, and politicians and technicians act as representatives (Cabanelas, 2018). The rise of citizen participation is contextualized within the crisis of representative democracy, accentuated by the economic crisis and a certain negative social vision of politics (CIS, 2012). In the last 20 years, this has led to the emergence of civic movements that demand changes to the current model of decision-making and demand greater citizen prominence in all public actions that concern them.1

Those governments who support participatory democracy seek to put an end to the distrust among officials of the decision-making capacity of the population. The promotion of citizen participation by each public administration leads to more transparency and legitimacy in its decisions. Moreover, the inclusion and integration of citizens and other concerned agents in urban regeneration actions guarantees the sustainable development of our cities (Rey & Tenze, 2018).

One key participatory democracy action is to involve more citizens in the city’s management model through decentralization and citizen participation to better serve the common interest and deepen the democratization of decisions (Rodríguez, 2007). In turn, this strengthens trust and joint responsibility for those decisions, building a better future for all.

Participatory democracy is citizen participation (Ramírez, 2014). In this way, any public administration can be an instrument of regeneration and democratic deepening, in which the affected citizens play relevant roles in the management of services. This encourages flexible and efficient formulas aimed toward community objectives and concerned with results, with a greater capacity to link the public and private spheres (López & Leal, 2002).

Currently, participation systems are extending beyond the social and economic spheres, being implemented within the requirements of territorial planning, in which urban planning is a key tool. The crisis of cities due to the inadequate response to urban complexity, excessive growth, and social segregation has rendered obsolete the classical theories of urban planning. Citizen involvement in the urban planning model has gone from an informative procedure to being fundamental for the development and implementation of new urban planning instruments (Rando, 2020).

For Boira (2000), urban planning has a direct influence on the lives of citizens, and he wonders how their opinions and feelings would influence the shape of the city. Therefore, the collaboration of citizens and urban stakeholders could contribute to reducing the failures that some cities suffer. In this regard, it must be borne in mind that, in terms of participation, public information is a prerequisite but does not constitute the participatory practice itself, which in many cases leads to confusion between the right to participate and the right to be informed (Parés, 2009).

Legislative initiatives on behalf of participation and transparency

High democratic stability stimulates the suitable development and consolidation of citizen associations, which translates into more cooperation and participation (Herrmann & Klaveren, 2016). The latest Eurobarometer survey on democracy and citizenship shows that European citizens are today more aware of their rights, as a result of the efforts of the European Union (EU) to encourage participation (European Commission, 2020). Citizen participation has great legislative support: from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948) to the Maastricht Treaty of the EU (2012). In Spain, the representativeness of society is established in the Spanish Constitution, which orders the public authorities to recognize and facilitate citizen participation. In addition, it promotes the free exercise of the rights and freedoms of Spanish citizens through the relevant regulations (Constitución Española, 1978).

For the Council of Europe (1983), the implementation of planning instruments must be carried out in a functional, democratic, global, and prospective manner. However, urban planning still has a long way to go in that regard. The Urban Agenda for the EU encourages the participation and civic collaboration of all the agents involved to build safe, accessible, inclusive, green, and quality spaces. It also urges governments to facilitate the identification of opportunities to improve urban areas (United Nations, 2015). The Spanish Urban Agenda, a non-regulatory strategic document, pursues the improvement of public space, including citizen participation in favor of transparency (MITMA, 2019). On the other hand, the Land Law establishes the right of citizens to participate in urban planning processes that concern them (Ministerio de Fomento, 2015).

However, some authors argue that in practice, participation has been little more than rhetoric, both in the EU and in Spain (Navarro et al., 2014). After all, the Land Law recognizes the right to participate but does not accurately regulate how to actively participate beyond the minimum consultative requirements. Participation has come to occupy an important place both in theoretical reflections and in political discourses related to the transformation of the city (Velázquez, 2016), but at the same time signifies a lack of real depth.

Citizen participation in urban planning

In Spain, the urban management and planning instrument used at municipal level is called Plan General de Ordenación Urbana (PGOU).2 The PGOU determines general aspects such as land classification, use restrictions, and the protection regime. It also includes the arrangement of equipment or the layout of infrastructures (Farinós et al., 2015). It involves a broad territorial strategy and foresees the future development of the municipality. To ensure the success of a new urban plan, it is important to involve the citizens and main urban stakeholders from the beginning. However, involving citizens is not an easy task since drafting a PGOU is an administratively complex and lengthy process in Spain, taking on average between 8 and 10 years.

The aforementioned Land Law establishes that Spanish citizens have the right to participate in the preparation, processing, and approval of municipal planning instruments, to be informed, to receive an audience and to exercise actions, to make petitions, to initiate procedures and popular consultations and to submit suggestions, complaints or claims (Ministerio de Fomento, 2015). The urban legislation provides for a regulated period of public information during the drafting process of the PGOU to improve the document and help the citizen consensus through the presentation of suggestions, complaints, and proposals. However, this process is not sufficient to effectively incorporate citizen demands, since it is foreseen as supervision after the drafted text. In the best of cases, if the drafting technicians incorporated the citizen complaints, which are not legally binding, the citizenry would be able to qualify some specific aspect of the PGOU, but the Law does not oblige or predispose to participation in the previous decision-making period fundamental to a plan.

Objective and hypotheses

This paper aims to ascertain the degree to which the largest Spanish cities have used citizen participation in urban planning. It also aims to define which cities and to what degree have involved their citizens in public decision-making as an expression of a desire for transparency. For this purpose, the revisions of the PGOUs of 25 Spanish municipalities with more than 215,000 inhabitants are analyzed, in the period of the last 20 years.

Even though participation is increasingly required at the international, national, and local level, some cities still involve their citizens exclusively through the minimum participation legally required. This participation is based on complaints and suggestions submitted by citizens during the public information period. That is to say, they merely develop a consultative participation. This participation model is not enough to incorporate citizens in territorial analysis or the generation of urban proposals, which would require more active participation. Thus, certain large city councils in Spain have taken a step beyond the norm in favor of citizen participation that reflects the feelings of the affected population.

Methodology: case study selection

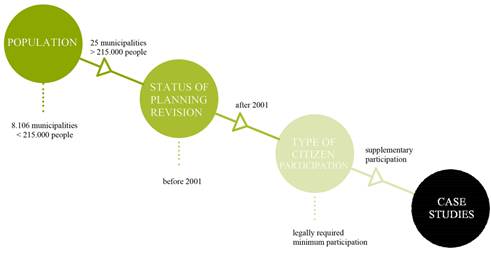

The case studies were selected and classified according to three parameters: population, planning review status, and type of citizen participation during the drafting of their PGOU (Figure 1).

Population data were obtained from the 2020 Spanish census of the 8,131 municipalities (INE, 2020). Classified from largest to smallest, the data set of the current study has been limited to the 25 cities with the largest number of inhabitants.

The next step involved identifying which of the 25 cities have revised their PGOU in the last 20 years. Based on the public information about the PGOU that each city has on its website, the appropriate classification was made. We found that seven of the cities have not reviewed their PGOU in the last 20 years and 18 have.

In the third step, cities that carried out a participatory process beyond the consultative one established by law were identified. All the legal documentation related to the PGOUs available on the online municipal portals was reviewed. A content analysis of the memorandums of the PGOUs was carried out to examine the drafting and participatory processes. It was noted that in the case of the municipalities that developed participatory processes, the majority also posted information about them on the municipal web pages. We assume that, due to the additional work undertaken above what is strictly required by law and the need for disclosure to successfully develop the participatory processes, the municipalities considered it mandatory to disclose the results of the processes online.

Finally, the participatory processes were examined to classify the different types of participation. In addition to the official information available in the memorandums of the PGOUs and on the municipal transparency portals of the institutions involved, the secondary data were complemented by qualitative information extracted from interviews with municipal technicians and technicians from some of the teams involved in participatory processes. To triangulate the information, news in local newspapers referring to the revision of the PGOUs and their participatory processes were reviewed.

The participatory processes carried out in these cities reinforce citizen involvement in the diagnosis of municipal urban problems, provide more suggestions and new perspectives, and promote the improvement and consensus of the outcome PGOU document. In this way, a more transparent and better accepted PGOU is achieved in the immediate future.

Results

Population analysis of Spanish municipalities

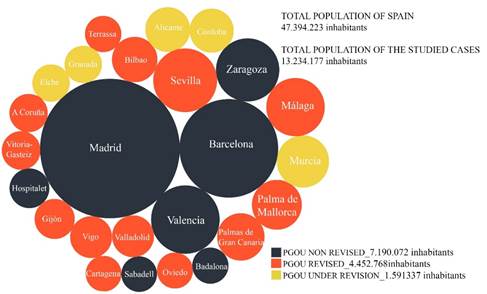

The municipalities studied, representing the 25 most populated municipalities, are shown on the map of Spain (Figure 2).

Planning status of the selected municipalities

Documentation of each selected municipality was studied to determine whether it had reformulated its PGOU since 2001. The phases of revision of a Spanish urban planning document include a pre-diagnosis or previous studies (not mandatory), writing the Advancement of the PGOU with mandatory public exposure, and finally, adaptation of the document for the Initial, Provisional, and then Definitive Approval by the city council. In addition, the final document must be submitted to the regional urban authorities to be examined and, in the positive case, definitively approved.

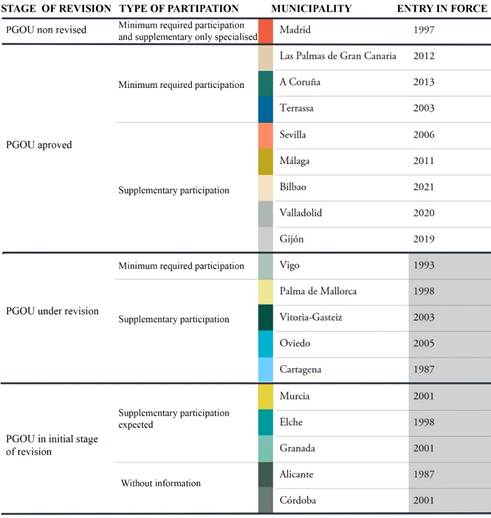

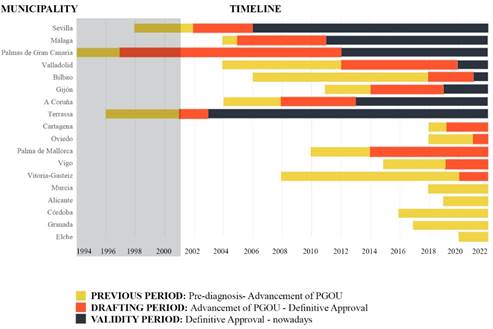

The selected municipalities showed different levels of planning and development, as reported below (Figure 3).

Source: Authors (2022)

Figure 3: Selected Spanish municipalities categorized according to planning revision status and population

Among the 25 selected cities, 18 (72%) had reviewed their urban plan between 2001 and 2021 or were in the process of reviewing it at the time of the study, while the remaining seven cities (28%) had not. Additionally, eight cities from the first group (44% of the total) have had their new PGOU definitively approved and come into effect. In five of the selected cities (28%), the document is in the drafting phase after the presentation of the Advancement. In the remaining five cities (28%) the reformulation of their PGOU is in an early stage of development, with no binding data currently available.

In accordance with both the regulatory tradition and the common objectives described in the PGOUs, the commonly accepted validity of a PGOU should be around 15 years. Consequently, it must be noted that seven of the studied cities have not reviewed their Master Urban Plan in the last 20 years, and those currently reviewing it have been doing so for a long time. Some cities, such as Alicante and Cartagena, have a PGOU in effect since 1987, representing a very outdated urban planning model. There is a notable variation in the timelines of the review process in the 18 municipalities that have reviewed or are reviewing their PGOUs in the last 20 years (Figure 4).

Source: Authors (2022)

Figure 4: Timeline of the reviewing process of PGOUs of the 18 Spanish municipalities selected as case studies

Although Seville, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, and Terrassa began reformulating their urban plan before 2001, they have been included in this study because the final approval was given within the timeframe studied. It was noted that some cities devote a long time to pre-diagnosis studies, such as Bilbao and Vitoria, whose studies lasted 12 years, with a shorter subsequent period to write their PGOU. On the contrary, in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Valladolid, and Mallorca, it took 15, eight and seven years, respectively, to draft the final PGOU for reasons discussed below.

Citizen participation throughout the revision of the PGOU

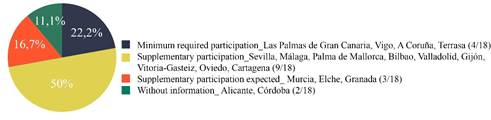

The type of citizen participation in the definition of new urban planning has different nuances, as mentioned above. For this study, a distinction has been made between participation required by law and supplementary participation (Figure 5).

Minimum citizen participation in urban planning as the only citizen expression

In Spain, the minimum mandatory citizen participation in urban planning is specified in the Land Law.3 It is essentially limited to information and compilation of suggestions, complaints, or claims throughout the public information periods. Four cities out of the 18 that have revised their PGOU have only applied the minimum participation required by law:

In Vigo (296,692 inhabitants), a very controversial PGOU was approved in 2008, only to be declared null by the Supreme Court in 2015 for not having the mandatory environmental assessment (Ayuntamiento de Vigo, n.d.). In 2019, a new PGOU was published and opened to public exposure. After that, it was approved by the Plenary of the Vigo Council in August 2021 and has been followed by a new public information process.

Las Palmas de Gran Canarias (381,223 inhabitants) began the review process in 1994 to adapt the PGOU to the new legislation. Although the Advancement of the PGOU was submitted for public information on two occasions (one more than required by law), no other supplementary participation was allowed. That document received 443 complaints. Six years later, the PGOU was initially approved. After the public information period, the document received 14,662 complaints, so it had to be rewritten to reach provisional approval in 2000. However, since this entire process took place before the Law of Territorial Planning of the Canary Islands entered into effect in 2000, the draft of the PGOU had to be readapted before its definitive approval to avoid suspension. The complaints received at that stage were such that the process had to be restarted. The final approval was reached in 2012. During this lengthy process, the degree of citizen participation corresponded to the regulated period of public information, where social disagreement was demonstrated. In this case, the lack of agreement with the concerned urban stakeholders and the lack of legal foresight contributed to the long delay in the review process.

A Coruña (247,604 inhabitants) and Terrassa (223,627 inhabitants) are two other cities that have developed their new PGOU with the minimum mandatory participation throughout the public information periods.

Supplementary participation in urban planning

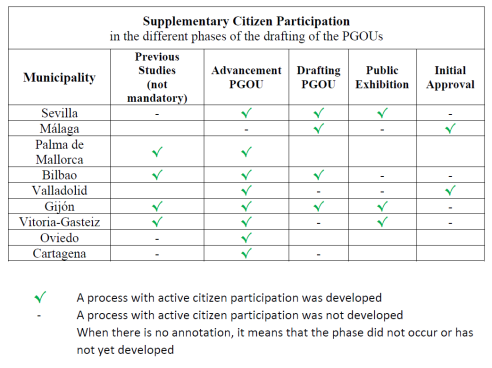

Supplementary participation is understood as participation that complements the minimum legal requirements and reinforces citizen involvement in the public aspects of urban planning. National law, although conceptually grandiose on participation, fell short in the requirement to develop active participation. Thus, some Autonomous Regions and municipalities have designed regulations at regional or municipal level that deepen the application of active participatory processes in their territories. With them, the City Councils can stimulate the collaboration of their concerned citizens in municipal planning through specific dynamics (Figure 6 and Figure 7). These participatory actions can be incorporated into each of the different phases of development of the PGOU and are aimed at citizens. Sometimes they also add the regulation and promotion of the qualified participation of experts in urban issues, such as academics, neighborhood associations, promoters, NGOs, and other interested stakeholders.

The following is a synthesized description of the supplementary participation processes developed in the cities studied, involving nine case studies plus a complementary case:

Source: Authors (2022)

Figure 6: Spanish largest municipalities that have revised their urban planning with some type of citizen participation

Seville (691,395 inhabitants) was the first Spanish city to actively incorporate citizens in the drafting of its PGOU; the review began in 1999 and was approved in 2006. The participation process was prepared by the Seville Plan Office, created ad-hoc, and integrated by technicians, experts, professional and neighborhood associations, citizens, and other urban stakeholders. Previous studies helped in the preparation of the Advancement, called Plan a la Vista (2000-2001). At that time, public debates were held with citizens and specialists. Once the Advancement (2002) was approved, the document was published and disseminated through various channels (talks, videos, posters, etc.). Subsequently, several parallel and supplementary participatory processes were carried out on specific topics that emerged from the working groups. Once the PGOU was initially approved, a public information period was opened with a general exhibition, several specific expositions in civic centers, and a neighborhood information point. In addition, cycles of talks, conferences, announcements, and various meetings were held involving professional, technical, and neighborhood associations, promoters, the media, etc. (Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, 2007). The willingness of the Sevillian City Council to involve citizens in both the analysis of the territory and during the preparation of the document, as well as to facilitate the communication and explanation of the new PGOU.

Another example of supplementary participation is found in Málaga (578,460 inhabitants), which approved its PGOU a ten years ago, and included citizen participation after the publication of the Advancement (2005). The process involved engaging with individuals and neighbors of the Municipal District Boards (Ayuntamiento de Málaga, 2010). After the Initial Approval (2006), the complaints from citizens were also collected (Cardador, 2016).

The review of the PGOU of Palma de Mallorca (422,587 inhabitants) began in 2010 with the campaign Imagine Palma. At that time, a first public information process in various media (newspapers, web, Official Gazette of the Community, etc.) was opened and citizens were invited to submit suggestions (Ajuntament de Palma, 2012). The drafting team was integrated into the Revision Office of the Department of Urban Planning and Housing. Prior to the Advancement, in 2013, an ‘Analysis and Previous Studies’ report was drafted. Various activities were carried out to promote citizen participation during this phase: a website was created to make contributions, there was a question contest, another for micro-stories, and a last one for short stories among schoolchildren. At the same time, a commission was created to plan sectorial meetings with social and professional agents, with a total of 70 representatives (Ajuntament de Palma, 2013). An external company drafted the Advancement, which was submitted in 2014 to be initially approved by the city council. This process could be summarized by saying that citizen participation was adapted to what the law requires and, in addition, citizens and experts were actively included in the analysis phase during the drafting of the Advancement.

In Bilbao (350,184 inhabitants), the review of the PGOU began in 2006. The city council set up a PGOU Office with the collaboration of municipal technicians and an external drafting team of architects, town planners, and communicators. In the pre-diagnosis phase (2009-2010), some activities were carried out to identify key aspects of the municipality through participatory methodologies. All of this culminated in the Participatory Diagnosis document (2012-2013). The Pre-Advancement phase (2016-2017) involved deliberative sessions, working groups, activities aimed at specific profiles (young people, children, university students, adults with training, professionals), sectorial working tables, online surveys, etc. (Ayuntamiento de Bilbao, 2017). The Advancement was submitted for public consultation in 2018 and was finally approved in 2020. It should be noted that the Bilbao City Council organized an ambitious and very complete participatory model with a wide variety of channels that included face-to-face participation in the previous diagnostic phases. These efforts consolidated Bilbao as one of the leading transparent cities (Ayuntamiento de Bilbao, 2011).

The Advancement of the PGOU of Valladolid (299,265 inhabitants) was presented in 2012 with a two-month public information period. The document was finally approved by the city council in 2015. However, in 2016 that decision was reversed to adapt the document to the new regional legislation and to incorporate new contributions made in the public debate process Thinking and Living Valladolid (Ayuntamiento de Valladolid, 2015). The citizen participation process consisted of an open-access discussion group to think about a city model with citizens and professional associations. After the Initial Approval in 2017, there was a new public information process. Subsequently, the PGOU was initially approved in 2019 and, definitively, in 2020. In Valladolid, the regional legislative change was an opportunity to incorporate supplementary citizen participation. This situation shows the interest of its municipal politicians in involving the concerned urban stakeholders in their decisions.

Gijón (271,717 inhabitants) had a quite disorganized urban design resulting from rapid population growth and poor urban planning (Latorre & Solá, 2016). In 2005 and 2011, there were two attempts to approve a new PGOU, but the courts annulled both. The 2011 attempt was annulled by the Supreme Court for not submitting “reports of fundamental importance” to public participation (Moro, 2015). After this setback, in 2013, the Official Association of Architects of Asturias prepared a public consultation and citizen participation process to develop a pre-diagnosis report and general planning strategies for the municipality of Gijón. This also gave way to a citizen survey. Both documents served as a basis to begin the revision and publication of the Priorities Document in 2014, an urban instrument that mixes the traditional Advancement and a Municipal Strategic Plan. At that time, neighborhood participation activities, contacts with social entities and a public exhibition of the document were developed. During the drafting of the PGOU there was a continuous participation process through debates, observations, assessments, and suggestions. There were two periods of public consultation after the Initial Approval in 2016. Five working groups were established to facilitate the exchange of ideas between citizens, city council officers, and the drafting team, with the aim of improving the urban proposals (UTE Ordenación Urbana de Gijón, 2018). There was also a mandatory period for presenting complaints during the public consultation. With all this information, the document was adapted to include the submissions obtained through the public consultation, and it was resubmitted for public consultation in 2017 before being provisionally approved by the city council in 2018. In this review of the PGOU, the participatory diagnosis and collection of suggestions established in the public exhibition favored the interrelation among citizens, technical professionals, and municipal politicians.

Vitoria-Gasteiz (253,996 inhabitants) incorporated the vision of urban stakeholders from a Previous Study phase (2009), during which there were sectorial working groups of specialized participation. Subsequently, before drafting the Advancement, a shared Diagnosis was carried out in 2013 with different citizen profiles. Activities were held in civic centers and rural areas, youth workshops, citizen forums, a World Café, and information sessions all over the city. In a subsequent phase, carried out in 2016, although it was not directly open to citizen participation, experts and municipal technicians made proposals. Once the document was presented to the city council, another participatory cycle was developed in 2019 during its public consultation to contrast the proposed urban solutions with the citizens. In this way, the Vitoria-Gasteiz City Council made a great effort to arrive at a social consensus that would allow it to approve the plan, even making a second participatory round.

The revision of the PGOU of Oviedo (219,910 inhabitants) began with the elaboration of a Priorities Document (Ayuntamiento de Oviedo, n.d.). This report was both a preliminary analysis and Advancement of the PGOU, which included the minimum legal citizen participation (with compilation of complaints) and a supplementary participation program (neighborhood meetings for debate and generation of proposals).

The review process of the PGOU of Cartagena (216,108 inhabitants) is currently ongoing. To draft the Advancement, a participatory process took place during the first months of 2019. Citizen workshops were held for diagnosis and generation of proposals, as well as technical working groups and interviews with experts, representatives of the city, and municipal politicians. The Advancement was presented to the public two months after the end of the participation process. Compared to other cities, the participatory period was relatively short due to the tight schedule imposed by the city council. The quality of the participatory work in formulating and compiling citizen proposals was notable. However, not all these proposals were subsequently reflected in the final Advancement presented to the city council.

It is worth mentioning the case of Madrid, which made an attempt to start the review process of its PGOU before being stopped. The Madrid City Council began the review of the PGOU in 2011, reserving participation to specialists in urban matters without expressly including civil society. Specialized institutional and technical participation took place in 2012-2013 through working groups with representatives of neighborhood and professional associations, trade unions, urban experts, universities, municipal politicians, etc. (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 2013). In addition, the Regional Federation of Neighborhood Associations of Madrid prepared a document that included the demands of the neighbors (Dirección General de Revisión del Plan General, 2013). Although the municipal plenary approved the Advancement documents in 2013, the process did not continue due to the political changes in the subsequent years (Gracia, 2014).

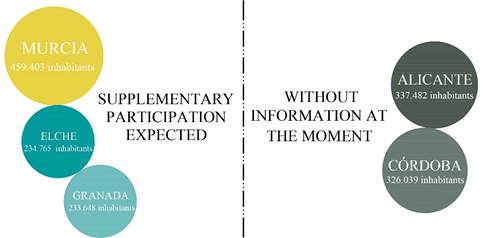

Revision of the PGOU currently in an early phase process

Among the large Spanish cities examined, five are currently in a very early phase of revision of their PGOU, where participation has not yet taken place or is not at a stage to be able to assess it (Figure 8). This is the case with Murcia (459,403 inhabitants). In 2018, the Polytechnic University of Cartagena prepared an urban planning report to serve as a basis for the revision of its PGOU. The city council also signed an agreement with the University to create an observatory of the PGOU, with the aim of continuing the revision process (Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia, 2020).

Source: Authors (2022)

Figure 8: Spanish largest municipalities that have just begun the revision of their Master Urban Plans

In Alicante (337,482 inhabitants), a PGOU was provisionally approved in 2009, which was judicially rejected by the Court of Alicante in 2015 due to corruption cases in the Alicante City Hall (Martínez, 2011). The municipality restarted the revision again in 2019, but there are still no verifiable data. In Córdoba (326,039 inhabitants), the processes to review its PGOU began in 2016. Partial revisions of the current plan continue without advancing toward a new proposal, due to the lack of municipal consensus (Ganemos Córdoba, 2017).

In 2020, the revision of the PGOU of Elche (234,765 inhabitants) began, to adapt it to new regional laws and to the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda. A public consultation was launched on the city council's web portal to submit proposals prior to the review. The survey closed in January 2021, and the local government has expressed its willingness to discuss the city model with neighborhood and professional associations, collectives, and trade unions. A similar situation is underway in Granada (233,648 inhabitants); the review began with a participative diagnosis delivered in 2019, and the drafting is ongoing after the contracting of external technical services in 2021 (Fernández, 2017).

Discussion

From the results obtained on the different processes analysed, some global considerations can be extracted as follow.

Source: Authors (2022)

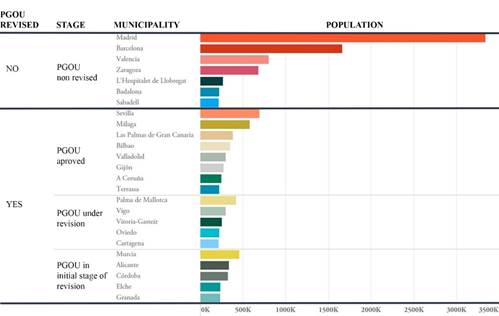

Figure 9: Relationship between the municipality's population and the revision status in the 25 largest Spanish cities by population

This study has found that, among the 25 largest Spanish cities, four of the five most populated cities have not carried out a review process of their PGOU in the last 20 years. Based on the number of inhabitants, Figure 9 shows that more than 7 million citizens of large Spanish cities (55%) have not been able to participate in the revision of their PGOU. Although some have been able to do so in more limited planning mechanisms that are not the subject of this article (e.g., partial, special plans or other forms of planning that do not affect the entire city). This may be due to these cities finding it more difficult to update their urban plans because of their size. This possibly slows down the progress of citizen participation in major issues such as municipal territorial planning and the urban future of their city, which should be addressed by political decision-makers. However, it is notable that large cities such as Barcelona, which has not revised its PGOU since 2000, is carrying out innovative participatory processes in smaller-scale planning instruments.

Among the 18 largest Spanish cities that reviewed their PGOU between 2001 and 2021 or which had a review process underway at the time of this study, the percentage of municipalities that have used or are applying any form of citizen participation is quite high: at least 66%, that is 12 out of 18. Meanwhile, 50% (nine cities) have incorporated participatory processes focused on citizens and experts in urban planning, and 16.7% (three cities) have expressed their intention to incorporate it. At the other extreme, 22% (four cities) have concluded the process with minimal citizen participation; only advisory participation required by national law. The remaining 11% (two cities) did not have sufficient information to be evaluated (Figure 10).

Source: Authors (2022)

Figure 10: Types of participation in the 18 Spanish municipalities selected as case studies

This analysis shows the intention of the majority of Spain's largest city councils to incorporate citizen participation in their urban planning.

Vitoria-Gasteiz and Bilbao stand out for including active citizen participation in all stages of development of their PGOU. They have had a duration and variety of formats that demonstrate the interest of the Basque Country administrations to engage in these issues. Finally, Seville is notable for, in addition to the above (consultative and/or dissemination mode), being a pioneer city in favoring the incorporation of citizen participation in urban planning in a proactive manner.

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate a real commitment by Spanish municipal administrations to include citizen participation in their urban policy to meet their demands. That means strengthening the democratic development of the communities and promoting the transparency of public administration.

A large majority of the largest Spanish cities have reviewed and updated their PGOU since 2000. More than half of the cities that have reviewed, or are in the process of reviewing, their PGOU have incorporated participation additional to the strictly legal requirements. This demonstrates the commitment of these councils to encourage the participation of their urban stakeholders It also indicates that the national law does not respond correctly to the current needs for citizen participation, which leads to the appearance of regional or municipal regulations in different territories. This causes significant differences both in the way participatory processes are applied and, in the results, obtained. Thus, it is concluded that there is a need to regulate a common framework that defines and delimits the minimum participatory processes required in the design of the PGOUs throughout the country.

The PGOUs that have managed to involve citizens more actively, not only in the information processes but also in the conception of the document, have achieved greater transparency, greater public acceptance, and better implementation of the final document. However, those that have been or are being reviewed according to the strictly legal participation mechanisms have been more controversial and difficult to approve due to lack of consensus.

After analyzing this sample of Spain's largest cities (hosting 30% of the total population of the country), more research is needed. On the one hand, on municipalities with smaller populations to confirm this positive trend of including citizen participation beyond what is legally required in Spain. On the other hand, the outcomes of the cities that have had complementary citizen participation policies in the development of their PGOU should be studied in depth. It is essential to build methodological proposals backed by success stories that consolidate an efficient urban regeneration model (Paisaje Transversal, 2016). There is still much to be achieved in the legislative framework and in the planning intervention methodology. Therefore, public administrations must continue the efforts to correctly implement new measures to strengthen the involvement of citizens and of the institutions themselves (Ganuza, 2010).