1. Cordoba in its territory: an indivisible reality

Way and beyond ideological mandates that have at any moment in time distinguished legal differences between the area falling within or without the city walls, history shows that ever since it was founded, Cordoba has surpassed the strict limits imposed by its walls to make up a functional unit in which it is impossible to understand the city sensu stricto without its extra moenia area, its suburbia: an ever changing reality whose first sign of transition centres on the network of roads.

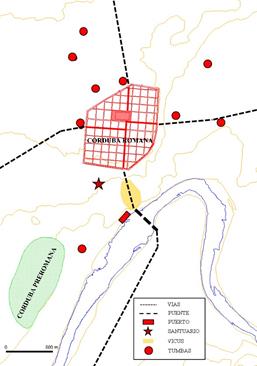

This in turn becomes a guarantee for access to a second outlying strip (lacking in urban functions but easily accessible and the area favoured by its inhabitants for their daily activities), and finally to the land on which the city’s economy, political power and prestige depended . The suburbs served as a mirror for the city, for better or worse, breathing with it, giving rise to city and outskirts as a whole in which neither part could exist without the other (figure 1).

The founding of Cordoba on the site it still occupies today was mainly justified by its control of the river, at a point where the landscape reflects a clear transition between two worlds: plain and Andalusia, hills and lowlands, barbarism against refinement, mining, cattle raising and hunting against the best land in Hispania for farming. In the times when the Baetis was still a wild river, with uncontrollable forces when it raged down, Corduba afforded perfect command over the only fords that allowed it to be crossed in times of low water and for many kilometres around, becoming a prototype of “bridge city” (Vaquerizo 2006b); a situation that must have soon moved on from simple metaphoric expression to tangible reality. On the other hand, the city dominated the middle valley of the river at the exact point above which it was no longer navigable (Estrabón, Geogr. III,2,3; Plinio, N.H. III,3,4). This allowed it to enjoy its own port and wharves (León Pastor 2009-2010), from which it could ship minerals from the hills and later oil, wine, cereals, wool, wax, honey, wood…, facilitating the entry of compensatory trade in exotic materials, luxury items, cultural influence of the most varied kinds, personalities from varied origin and especially troops, supplies and impedimenta.

All of these factors explain the privileged and dominant role that urban Cordoba played in the region’s geopolitical and territorial organisation from its remotest origins, as well as its cosmopolitan air, its multicultural character and its extraordinary strategic value, at a time when communications were a given for any initiative, and when having an ideal place at one’s disposal for billeting and supplying troops was a guarantee for conquest and sustainable power (Vaquerizo & Murillo 2010b; Vaquerizo 2014).

2. Vetus urbs

After decades of coexistence with the former indigenous city (Murillo et al. 2009, 57), the length and extent of which are uncertain, in the middle of the II century B.C. (archaeologically confirmed) Rome undertakes a new foundation, perhaps by then colonia Latina , to the northeast of the old Turdetan city, to which it gives the same name: Corduba (Carrillo et al., 1999, 40; Murillo & Vaquerizo 1996, 41 ff.; Murillo & Jiménez 2002, 184). A spur is chosen that is well defended (except for the north) by steep hillsides and several streams, situated about 750 m. north-west of the original indigenous settlement, from where it controlled the fords across the river and also the adjacent land, truly a paradise for the Italic colonization.

With an area of 47.6 Ha (one of the largest among the contemporary Roman and Latin colonial foundations ), republican Corduba is equipped from the outset with a surrounding wall (Murillo & Vaquerizo 1996; Ventura 1996, 138; Carrillo et al. 1999, 42, Fig. 2; Murillo & collectively, in Vaquerizo & Murillo 2010, a and b, and Vaquerizo 2010, a and b, 2011 and 2014, Works to be consulted for deeper insights.

Figure 1: Location of Corduba, capital of the Hispania Ulterior Baetica province, and hypothesis of the limits of Ager Cordubensis, with urban, suburban, periurban and rural areas. © Convenio GMU-UCO.

Jiménez 2002; Murillo 2006) that will remain unchanged until, in Augustus’ times, it is extended down towards the river, enlarging the urban space to 78 Ha. The route of the first ways (Melchor 1995) date to these times, and the mass exploitation of the mines in Sierra Morena Rome needs silver to pay its troops-, that favour the enrichment of the first Cordobese family sagas (García Romero 2002; Ventura 2009), and undoubtedly the building of the first bridge, whose existence has been proved beyond doubt by its prominence in the defence of the city during the Civil Wars (Bell. Hisp. V, 3-5; cfr.Rodríguez Neila 1988, 260 ff., and 274; Melchor 1995, 94-95).

As was usual in this type of foundations, the city was organised around an octagonal urban network, still without a sewage system, based on insulae of two actus (70 x 70 m; cfr.Carrillo et al. 1999, 46-47), which, initially with a high degree of building modesty, would not be completed until well into the I century B.C. (Murillo & Jiménez 2002, 189). The existence of a forum -and the role of Corduba as a provincial seat for the pretor- is documented in written sources at least since 113/112 B.C. (Cicero, In Verr., 2, 4, 56; Bell. Alex., LIII, 2), although the stratigraphic sequence seems to predate its construction to the middle of the II century B.C. (Carrasco 2001, 205).

Important artistic activity has been detected in the architectural decoration as from the first half of I century B.C., perhaps on the part of native workshops that worked with hard local stone but who still showed a high degree of dependence on Italic masters (Márquez 1998a, 203 ff, and 2008, 31).

We have hardly any information on religious architecture, although there is an important TuscanDoric style complex built from local sandstone which, in the opinion of its excavators, monumentalised the entrance to the city in the south, beside the access to the cardo maximus at the beginning of I century B.C . Placing it at this point, as well as highlighting the value of the cardo maximus as the city’s main axis, would also be justified by the vital role that the river and its port must have played in everyday life and its very existence, not only from a political point of view, but economic, strategic and even ideological .

A religious interpretation has also been given to the drums of the columns with twenty flutes, worked in limestone and stuccoed, that were reused on the wall in the Augustine refoundation in the Maimonides Square, becoming one of the earliest examples of the use of spolia (rediviva saxa) in the city, which would later become so frequent in late Roman and Ancient times (Moreno Almenara & Gutiérrez 2008).

During these first times, prior to the construction of the different aqueducts that would successively lead to Corduba becoming one of the best supplied cities in the Roman West, the houses still used water from wells (Ventura 1993b and 1996, 27 ff. and 67 ff.; Ventura et al. 1996, 95 ff.; Jiménez Salvador & Ruiz 1999, 88 ff., Fig. 6).

We have even less data concerning the suburbs (Figure 2). The Bellum Alexandrinum (LIX, 2, and LX, 1) mentions that when Casius Longinus returns to the city to face the troops commanded by M. Claudius Marcellus Aeserninus in 48 B.C. he demolishes the nobilissimae carissimaeque possessiones Cordubensium that existed on its outskirts, which seems to confirm the existence of important agricultural or recreational concerns in the suburbs or outskirts, in spite of the lack of any clear archaeological data. However, the first suburban villa of which we have archaeological evidence is Cercadilla, from I century A.D. (Moreno Almenara 1997).

The lack of evidence is common for the republican period throughout the whole of the Ulterior -but not for certain areas in the North-east -, for the moment without unanimous agreement to explain the causes (Rodríguez Neila 1988, 241 ff.; Murillo & Jiménez 2002, 193).

As far as funerary questions are concerned, we underline the almost complete absence of burials assignable to this period; surprising, but once again, not exclusive to Corduba. Maybe the necropolis corresponding to the republican city -situated on the highest part of the hill- was set on its southern flank, between the wall and the river; after Augustus’ deductio this area would be absorbed into the new urban precinct, which would mean that its use as a cemetery would then be entirely annulled. This seems to be confirmed by the existence of a possible funerary monument of unconfirmed type (built of ashlars, clad in limestone slabs and probably stuccoed and painted), found beside a way leading from a non-located gate on the southern wall and finally dismantled for the construction of the colony’s theatre (15 B.C.-5 A.D.).

Not far from here a fragment of titulus sepulcralis was recovered -a block of micritic limestone for embedding- dedicated to Bucca, servant to the Murria family in the late-republican era (Monterroso 2002, 135 ff.; Ruiz Osuna 2007, 98-99 and 125; Plan 9.1; plates 53-54; Vaquerizo 2008, 6 ff). The first phase of the funerary precincts could be dated back to the beginning of I century B.C., on which decades later the Puerta de Gallegos burial mounds would be erected, in the western necropolis (Murillo et al., 2002, 251 ff.; Vaquerizo 2008 and 2010a).

3. Nova urbs (figure 3)

Half-way through I century B.C., in the Civil Wars between Caesar and Pompey’s sons that would signal the end of the Roman Republic, Corduba took the side of the Pompeians, thereby provoking its destruction by Caesar’s army. After this, it went into a logical period of decline which ended when it gained favour with Augustus, who, certainly before 14 B.C. refounded the city by way of a deductio of war veterans from the Cantabrian wars. These are ascribed to a new tribe: the Galeria (earlier ones belonged to the Sergia), it is raised to the category of colonia and is assigned the patronymic of Patricia (perhaps alluding to its return to the patres), seeking to condemn the Turdetan name to oblivion .

In the opinion of A. Ventura (2008a), however, this new Colonia Patricia (perhaps Iulia?) might have taken its cognomen from Caesar himself, and its refounding deductio in 44 B.C. may have been the work of C. Asinius Pollio, proconsul in the Ulterior, which would include its new inhabitants in the t. Sergia, maintaining for several decades the members of the t. Arnensis of its initial founder (M.C. Marcellus) within a different administrative reality (the Corduba latina prior to 45 B.C.), to which the Cordobese quoted in sortitio Ilicitana might belong. In support of his interpretation he uses the alleged location of the auguraculum (decorated with stone slabs in bell-like tradition) used by Asinius Pollion for his work of auspicatio and inauguratio in the western suburb, following the pattern used in palatial Rome. However, excavations carried out at various points along the Nova Urbs wall lead us to place its chronology between the eras of Tiberius and Nero, seeming at first sight to be an unreasonable decalage to take such an ingenious hypothesis into consideration (Murillo, 2010; León Muñoz & Murillo 2009, 406).

Even when defeated and destroyed, what would be a Colonia Patricia for only a few centuries continued to play a directing role in official politics in the provincia. Here the imperial mint is situated, possibly founded by Agrippa in 19 B.C , from which came an enormous quantity of coins in bronze, gold and silver during several years, to pay the troops and the conquest of Hispania, showing once more the city’s extraordinary economic capacity, associated to the mineral riches from Mons Marianus and the activities of its argentarii (GarcíaBellido 2006; Ventura 1999 and 2009). Thus, in just a couple of generations the new colony rises from its ashes and, now conscious of the unprecedented political order represented by Augustus’ principality, casts aside its republican ideals, widens its precinct, provides itself with the most important elements of any Roman city (simulacrum Urbis) and turns them into an active element of self assertion, propaganda and prestige before the rest of the Empire and the world .

From the very first times of Augustus, the city started to equip itself with various aqueducts that absorbed the liquid element from some of the springs and fastest flowing and cleanest streams in the hills, responding to the precepts gleaned from tradition and treaties on hydraulic engineering. Of the three already identified (Ventura 1993b, 1996, 2002, 2004 and 2008b; Moreno Almenara et al. 1997; Borrego 2008; Carmona, Moreno & González 2008; Pizarro 2014) we know the names of two of them from the epigraphy (Figure 4): Aqua Augusta (later, Vetus Augusta), and Aqua Nova Domitiana Augusta, constructed at the beginning and end of I century A.D. respectively. The third one, perhaps identifiable with the name Fontis aureae in certain late sources (Ventura 2008b, 292 ff), as between II and III centuries A.D. The first two supplied about fifty thousand cubic metres daily, a figure taken globally and perhaps exaggerated, and this ensured the citizens’ private consumption, a permanent supply to the thermal baths and to the fountains dotted around the city; many of these, like the aqueducts themselves, the work of great local sponsors (the case of the duumvirate Lucius Cornelius), who dedicated part of their enormous wealth to city services and resources, thereby guaranteeing their place in the collective memory, and at the same time ensuring they occupied public posts (Melchor 1994; Ventura 1999 and 2009; Stylow, Ventura 2006).

The via Augusta, soon bordered with funerary monuments of different kinds which always sought the busiest stretches, but also the prestige lent to any construction of these characteristics on an artery of communication with the added value of connecting directly with Rome, entered the city in the East, following the right hand bank of the Baetis. Its original route had to be redirected about thirty metres to the North to allow for an important remodelling of the zone that included the reorganisation of the necropolis, the creating of a new residential district, the construction of a second aqueduct and the carrying out of a well designed architectural landscape, conceived in Claudio’s era and set up on three large terraces reached by way of the city’s two decumani maximi (Murillo et al. 2003; Garriguet 2010; Murillo 2010) (figure 5): the upper one, a square with porticos; in the middle, an open space dedicated to grand ceremonies and circulation, and the lower one occupied by the largest building for spectacles in the city: the circus .

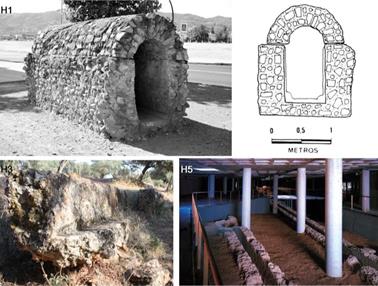

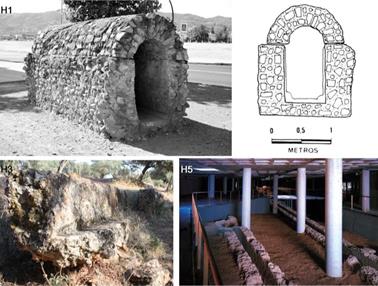

Figure 4 Main aqueducts that supplied Colonia Patricia. H1: Aqua Augusta Vetus; H3: Aqua Nova Domitiana Augusta; H5: Albaida or Bus Station aqueduct (Fons Aurea?). © Convenio GMU-UCO.

These three spaces, joined together, made up one more ideological expression . related to models well known in the metropolis (Augustus’ house, temple to Apollo Palatino and Circus Maximus) or Tarraco, and once again -although unanimity does not exist with regard to this hypothesis- directly related to official State worship, in this case with the provincia as protagonist, wishing just like the city to express submission and fidelity to the Imperial idea. In full aurea aetas, characterised also by an extraordinary economic boom, the peoples of Cordoba decided that their dedication to the Imperial cause needed a more explicit manifestation of publica magnificentia, and to this end did not hesitate to undertake one of the most ambitious building projects known until then in the urban complex, which affected 10 hectares of its eastern sector, led to dismantling a stretch of almost 100 metres of the Eastern wall and forced streams and torrents to be diverted, with the consequent infrastructure and drainage works. Nobody throughout history has ever had such a clear idea as Rome regarding the ideological importance of the urban image, and its role at the service of politics.

Figure 6 Drainage infraestructures beneath one of the streets in the western suburb of Colonia Patricia, in the proximity of the amphitheatre. © Convenio GMU-UCO.

The upper square stands above the wall with the idea of making the most of the height afforded by the hill, and reinforces its stability with a line of digital foundations in the shape of anterides, in Vitrubian style. In the central section (receding towards the western porticus in order to free up space in front of the facade) it houses a hexastyle, pseudoperipteral, Corinthian temple, built of local stone and clad in marble, possibly from Carrara. It faced an ample sector of ground to the east (which it adjoins), turning the temple with its bearing and height into the first noble, immutable, magnificent view of the city that any travellers arriving from Rome would see. The square, somewhat irregular, eighty-five metres long on its main axis, framed by a triple porticus that left the eastern side free, was adorned with numerous marble and bronze statues, some of them equestrian.

The circus, of more than considerable dimensions, flanked the east-west way, on an axis somewhat different to the temple. We only have evidence of a limited sector of the sustaining walls of it northern stands. Its construction would last until Nero’s times (perhaps even Flavian), and it would be used for little more than a century, as it would cease to be used as from an undefined moment in the last quarter of II century for not very clear reasons that would lead to the abandonment of the middle square and the displacement of worship to the Emperor (quite weakened since the end of the previous century), with all its paraphernalia, to another place that has yet to be identified . The circus would never be rebuilt; however, epigraphy (CIL II2/7, 221) explicitly confirms the celebration of ludi circenses in the city in the first half of III century A.D., so we cannot rule out the possibility that after being dismantled it was reconstructed elsewhere in the city (perhaps made of wood and only for temporary use?) on a site that has still to be identified .

The conceiving of the eastern urban facade with its grand monumental arrangement, opening as we have said onto the via Augusta, should not be separated from what took place more or less at the same time in the western vicus with the building of the amphitheatre, which also compelled alterations to be made in the via CordubaHispalis route and is accompanied by fresh urban design in the zone (in this respect, Vaquerizo & Murillo 2010a). Here we must underline the construction of a colossal avenue, sixteen metres wide with a double portico, under whose pavement ran three large sewers: the centre one designed to drain the amphitheatre itself, and the ones on each side to collect water from the porticoes (Castillo; Gutiérrez & Murillo 2010) (Figure 6); all three spilling into the stream of what would later be called Arroyo del Moro, which emptied into the Guadalquivir after serving as a natural ditch for the city on its western flank and would periodically cause flooding in the zone, well evidenced until it was channelled once and for all in XX century. Such an important urban undertaking would be directly linked with the reinforcement of the city’s East-West axis by way of its decumani and its greatest and most representative civic and religious spaces that began to be interpreted as via sacra, conceived perhaps as a “cosmography” of the Empire (Gros 2009, 334 ff.; Garriguet 2010, 474 ff).

With an axis of over 178 metres (we still work with provisional data), the patrician coliseum falls within the series prior to the canonical definition of its kind that would lead to the construction of the Flavian amphitheatre in Rome. The former has a solid ground plan, with large substructiones of ashlars entirely filled with construction materials and on which the stands are built (Figure 7).

The first excavations have yielded already the remains of architectural decoration in marble, which undoubtedly embellished the complex, and also of reserved seating in to have been important enough. What does seem to be relevant, on the other hand, is the political instability, derived precisely from the mauri crises, from rebellions and usurpation attempts started by Cornelius Priscianus in 145 and continued by Maternus in 187, and, fundamentally, the civil war that devastated Gallia and Hispania as a consequence of the conflict from 195 to197 between Clodio Albino and Septimio Severo after Comodo was assassinated in 192. The support of Clodio Albino by Hispania and the later repression of his followers by Septimo Severo, with numerous executions and systematic confiscations (Pérez Centeno 1990) would have a profound repercussion in the provinces of Hispania, as epigraphic documentation begins to reflect in Tarraco and in the Colonia Patricia archaeology. In the latter context, in repression of the provincial elites in Baetica, it fully explains the dismantling of its seat and the transfer of all its signs of dynastic worship to the the same material (Figure 8) . The patrician amphitheatre was in use from the late Julia-Claudio era until the end of III century or beginning of IV A.D., and according to all the signs would eventually be Christianised, as in the case of Tarraco, after several Cordobese martyrs had been executed (vid. infra). However, to date we only know for sure that it was subject to continuous pillaging for centuries, and on top of which an arrabal (suburb) would be built in the Islamic era which fossilised its ground plan. Nearby there must have been a ludus gladiatorius hispanus, which specialists seem to agree on situating in the Colonia Patricia (Ceballos 2002; Sánchez Madrid & Vaquerizo 2010). All of these aspects are dealt with in detail by several authors elsewhere, so we will not go any deeper here (Vaquerizo & Murillo 2010a).

With its enlargement, the city extends the perimeter of its walls down to the Baetis (the construction of which will last until Nero’s times), and they become the main urban defence against its floodwaters; in a clearly explicit alliance between both, as in so many expressions of Roman culture, they merge purely functional questions with characteristic monumentality, symbolic aspects and the city’s declarations of self importance. The gate, the bridge and via Augusta (formerly via Heraklea, of enormous value in the conquest of Hispania) make up a third scenario that in this case ennobles the meridian flank of the Colonia Patricia fronting its most emblematic and defining element: the river.

With respect to the way, restored by Augustus himself, we have scarcely any information, but the bridge, which must have been around three hundred metres long, is today the object of revision and study, so it is possible that shortly it will reveal something more about its construction in Roman times.

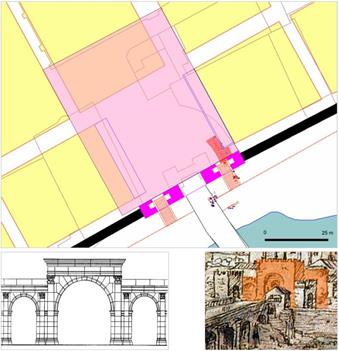

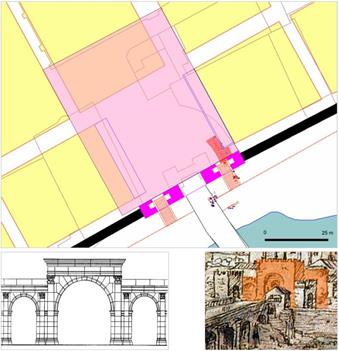

Finally, the gate, which would not be finalised until Claudio’s era, had three openings, the centre one aligned with the bridge, and the ones on either side with gateways to a large square (minimum 40 x 35 metres) which ennobled the Access to the inner city, also joining up with the cardo maximo (Carrasco et al. 2003). From the gateway one could also descend directly to the river: this is shown by the steps documented on the eastern opening, upstream, which would have connected with a dock or jetty designed also, right by the wall, to protect the city’s southern flank against the enormous floodwaters of the Baetis (Murillo et al. 2009, 62 ff., Fig. 14) (Figure 9).

In the neighbourhood of the bridge, there were factory zones of different kinds, such as potteries (Vargas & Carrillo 2004) or installations for putting into containers and exporting oil (Morena, 1997), and nearby must have been the river port (León Pastor, 2009-2010), probable boasting its own forum to bring together warehouses and mills (laid out on either side, within and perhaps without the walls), seats of different commercial societates, tabernae of every kind and temples or sanctuaries dedicated to exotic divinities, to judge by the odd inscription recovered in the zone that shows clearly the city’s degree of cosmopolitanism ; unless all of these activities were carried out in the square itself that monumentalised the entrance from the Gateway to the Bridge, referred to earlier. This entire zone underwent its first transformation in the course of II to III centuries, when the eastern gateway to the square was occupied by tabernae, and would see an increase in its commercial character, suffering an important process of urban degradation as from IV century, without being abandoned, as happened with the colonial and provincial forums. This probably explains its severe transformation in late-ancient times (Carrasco et al. 2003; León Muñoz & Murillo 2009; vid. infra).

Figure 8 Funerary epigraph from the Camino Viejo de Almodovar necropolis and seat reservation in favour of a public slave in Colonia Patricia, from excavations in the amphitheatre. © Convenio GMU-UCO.

Figure 9 Gate to the Bridge and adjacent Square, in the area of the docks in Colonia Patricia. © Convenio GMU-UCO.

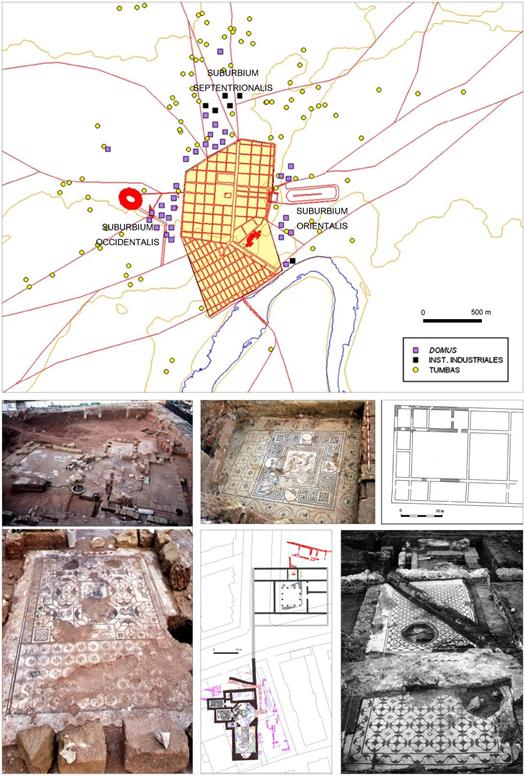

Finally as from Claudio and Nero’s eras, dwellings had spilt outside the walled precinct around almost all its perimeter, greedily extending themselves in the form of suburban districts around the city (Murillo et al. 2009; Vaquerizo, Murillo y Garriguet 2010; Cánovas 2010; Vaquerizo 2014), until they annulled to a certain degree the industrial and funerary uses of the suburbia , some of whose funerary monuments were dismantled, covered up or absorbed into the new buildings . If anything characterises the suburban areas it is to have traditionally served for funerary deposits, thereby establishing a clear separation, with a limiting characteristic, between the world of the living and that of the dead (Figure 10).

The latter are aspects well known in Cordoba thanks to numerous recent studies , that have for the first time drawn a topography for the Cordobese necropolis for the Roman era guided by sepulchral, monumental and well planned viae (in spite of the fact that in time this primitive planning would fade), that were similar in every sense to the ones in the most Romanised cities in the Empire . However, the tombs did not spread in a continuous and uniform manner in the areas dedicated to necropolis , but, apart from existing hand in hand with other kinds of structures and activities: traffic, religious, domestic, entertainment, manufacturing, hydraulic, agricultural, fluvial , unhealthy etc. (Fernández Vega 1994, 144 ff), must have occupied zones that were more or less limited, perhaps taking up free space left by the former, or according to some kind of criteria such as that of social classes and/or specific type of economies, family groups, or even collegia funeraticia. Thus it can be seen for example that in latter time, in the Santa Rosa district, where more than two hundred burials (Morena & Botella 2003, 408) were found in one plot whilst in the adjacent one there were none (in this respect, cfr.Vaquerizo 2008 and 2010a). These are circumstances to be found throughout the whole of the Roman era, giving rise to a funerary topography with absolute mobility whose landscape evolves hand in hand with urban development (on this problem, as far as statues are concerned, vid.Garriguet 2006, 201 ff.).

4. Workshops and guilds

In Cordoba as from late Republican times intervention seems clear on the part of workshops and guilds brought from the Metropolis, perhaps even itinerant ones that would have been responsible for the rapid establishment in the city of new official parameters in urbanisation and public architecture; somewhat later, as is logical, in the private sector, especially the funerary one, although they used the same language. Even so, judging by the archaeological information, and at least up until the Augustan refoundation, we can also assume an important role in public and private monumentalisation on the part of native workshops, not familiar at first with the new techniques and models, that would work as tradition demanded, progressively and inexorably adapting to clients’ demands, fashions, materials and architectural and sculptural patterns, until they merged in their own right with the artisans who had come from afar (León Alonso 2001). This full integration would become tangible from the very moment at which it would no longer be possible to distinguish traces of localisms in provincial artistic works; even though certain details of casticism would survive for centuries in portraits (Murillo et al. 2009; Vaquerizo 2014, with earlier bibliography).

In fact, a profound turning point is observed as from the construction boom in the city after its status is raised to that of Colonia Patricia, coinciding with a process of unprecedented ideological reconversion that would end up by catching on in all walks of life, including the funerary sector. The latter especially favourable to grand shows of privata luxuria, embodied particularly in the form of large domus outside the city walls , and monumenta that rivalled in location, size, luxury and originality. The people who ordered them (members of the urban elite, either through social importance or purchasing power who must have found in the funerary world one of the best ways to express ideological dedication to the new culture, to the new idea of State, to the new political regime and to the Emperor in person), did not hesitate to bring master craftsmen and artisans from the Urbs; in reproducing and sometimes elaborating fresh prototypes; in trying out sophisticated and unprecedented hard stone (marmora) as active elements of a hitherto unheard of symbolic and prestigious language , destined to reach the very highest level of adaptation to fashions and the new ideology; or what is the same, to self presentation and also, as a last resort, to perpetuate their memoria.

As in the rest of the Empire, this panorama underwent a determining transformation with the Christianisation of the Hispano-Baetic society, which would gradually lead to new ways of understanding funerary spaces. Already before this, in many of the cities in the south of the peninsula burials had invaded space inside the walls, clearly showing the change they suffered from an economic, social, cultural and urban point of view in the final stages of Rome’s power (García-Dils et al. 2005). This practice intensified over time until the dead occupied former urban spaces of relevance (Pérez Rodríguez-Aragón 1997, 629 ff., nº 11-13, fig. 4, 9-10; Corrales & Mora 2005, 133, figs. 112 and 113; Corrales 2005, 128, fig. 7), as happened in Astigi with the forum and its surroundings; in Malaca with the theatre (Roldán et al. 2006, Vol. I, 423 ff); in Carteia with the forum and thermal baths (Ruiz Bueno 2013), or in Corduba at the back of the grand public square centred on the temple in Claudio Marcelo Street (Costantini 2010). This process began to be detected towards the end of the Empire, coinciding with an intense shrinkage of the city’s role as umbrella to public and economic life that probably led to a change in how it conceived itself; to the beginning of a period of transformations that would culminate in its conversion into a mediaeval town.

In short, with the end of the Empire, the suburbs seem to invade the old urban area (of course, not only in Hispania) and, as is logical, this brings death. These are times of change that finish off the ancient city, so the old precepts that maintained it lose all value. Even so, the dead seem to remain faithful to tradition and only penetrate areas and buildings abandoned earlier, thus maintaining their frontier spirit, a certain respect for the people who live in urbe, who eventually may share the same space but as a general rule mostly distance themselves, congregating to live -or scratch a living- in smaller nuclei.

5. A city in transition

The image of Corduba, with her main public works fully completed by the beginning of the Flavian dynasty (Murillo 2010), was to remain the same until the last decades of the II century, when the first changes became perceptible. Later on, by the middle of the third century, the city’s monumental splendour during the previous two centuries began to wane: public buildings ceased to be erected, and the imported materials lacked their customary quality and quantity ; the workshops that produced sculptures and architectural decoration became less affluent; century-old houses were still inhabited, and the use of spolia as well as the recycling of some public and private spaces became common practice. This was the case indeed with a large number of funerary monuments (cfr. Moreno Almenara & Gutiérrez 2008, 78 ff. about the burial mounds of Puerta de Gallegos), the thermal baths, the circus, the colonial and provincial forum (including the temple on Claudio Marcelo Street, which appears to have been reconsecrated), or the amphitheatre. However, each of these places underwent a different transformation process: while the first was razed to its foundations to allow for quick and easy storage of materials, the latter was Christianised.

Many Roman streets were still used, but the pavements tended to be generally neglected and were repaired with gravel and even recycled architectural decorations, for example the Via Augusta near Saint Andrew’s church. Similarly, some cesspits began to fill up, while the lacus that used to distribute fresh water at the crossroads of the old Colonia Patricia stopped working , and the stream of the western pit that served as a main collector for several drains under the decumani of the westernmost section of the “vetus urbs” was repeatedly filled in and sealed throughout the fourth century.

The first important change to the urban image of Colonia Patricia since the beginning of the last third of I century A.D. took place precisely outside the city walls, on the eastern side of the great monumental axis formed by the double decumanus maximus (Fig. 11): in the last quarter of II century, the circus was abandoned and turned into a quarry (and consequently pillaged and razed to the ground). At the same time, the paving of the central terrace of the architectonic complex devoted in the prouincia Baetica to imperial worship was taken down, and a wall was erected to close off the eastern side of the square on its highest terrace, which had so far remained open (Murillo et al, 2003 and 2009a).

The III century also witnessed a gradual pattern of neglect of the western vicus on the other side of the city. This began before the amphitheatre’s abandonment during the first decades of IV century, to be precise after 303-304, the years that saw the execution of Saint Acisclus, the most important of the five local martyrs . Shortly thereafter, Cordoba’s coliseum underwent a hasty and thorough dismantlement caused by the increased demand for building materials. After extensive consideration of the city’s general archaeological and historical context, we can venture three different explanations for this:

An almost complete reconstruction of the bridge, a possible hypothesis (although highly improbable and as yet unproved).

A general and extensive refectio of the city walls, a little out of keeping with its constant maintenance requirements.

The erection of the monumental complex of Cercadilla, in our opinion the most likely hypothesis due to the proximity of both buildings and the existence of archaeologically documented mine-waste tips, containing spolia from the amphitheatre destined to the construction of the above-mentioned complex, and lying between the two (Fuertes, Rodero & Ariza, 2007).

Figure 11 Principal urban and suburban transformations throughout III and IV centuries a.D. © Convenio GMU-UCO.

In our view, the general interpretation of the building of Cercadilla is correct except for a couple of details: the very short time frame proposed for its construction (296297), and its consideration as imperial palace for Maximian Herculius in the context of his North African campaign . In fact, after the martyrdom of Saint Acisclus, Cordoba’s coliseum was stripped down to its foundations, including facade and cavea, whereby the pillaging was especially evident in its north-eastern section, the one closest to Cercadilla. Thus, it became a veritable “mine” for the construction of the new architectonic complex, clear proof of which we find in the “refuse tip” containing spolia recovered a mere couple of years ago at the former army quarters of Saint Raphael (Torreras 2009; Fuertes, Rodero & Ariza, 2007), located halfway between both buildings and including several seamed voussoirs from the vault of the ambulacrum, as well as some pieces carved in grey micritic limestone with a very peculiar physiognomy, and perhaps formerly part of the enclosed seats of honour of the proedia (Murillo et al, 2010a, 262-284, fig. 106, 107 and 109).

Figure 12 Christianisation of the suburban areas in Corduba (IV-VI centuries a.D.). © Convenio GMU-UCO.

Due to the distinctive construction technique employed at Cercadilla, most of the amphitheatre’s seating must have been fragmented with the aim of either adding it to the caementicium or re-carving it to produce the tiny vittatum that frames it. Even then, great calcarenite ashlars were obviously hauled and situated, for instance, near the skylights of the crypto-porticus, in many cases bearing the typical anathyrosis so characteristic of the coliseum’s building style (Hidalgo et al, 1996, 22, figs. 1618. Murillo et al. 2010a, 252 ff, figs. 90, 91, 96 and 98). Final evidence is provided by one such piece near the foundations of the monumental door that provides access to the complex (Hidalgo, 2007), consisting of grey micritic limestone and identical to the ones found at the army quarters of Saint Raphael. The excavators agree as to its being repurposed (Fuertes, Rodero & Ariza, 2007, 177).

If the date of construction of Cercadilla could be set approximately within the first decades of IV century, instead of being placed rigidly to match the hypothetical stay in Cordoba of Maximilian Herculius, we would gain a new perspective to tackle many of the open questions posed by Arce (1997 and 2010) in a more ample historical context, not only free from the limiting boundaries of the Tetrarchy, but also in direct connection with the dynamics of the suburbium itself. In fact, we would situate ourselves in a time frame ranging from the announced and voluntary renunciation of Diocletian’s and Maximian’s imperial functions in 305 to the obtainment of individual and personal power by Constantine in 323, an event charged with unique significance. Indeed, during the first two thirds of his rule Constantine was just another tetrarch, but the events that he endeavoured -or was forced- to set in motion were to change everything.

We are inclined to believe that Constantine built Cercadilla to serve as praetorium - from 307 or 308 - for the vicarius Hispaniarum and to ensure the correct administration of the Hispanic provinces. His aim was to reorganise his territories and mobilise the resources that, in the long run, would enable him to beat his rivals (first Maxentius and, later on, Licinius) . However, we endorse Hidalgo’s hypothesis (Hidalgo, 2002, 344 ff) which links the later years of Cercadilla to the figure of Ossius, bishop of Cordoba, counsellor to the emperor and prestigious personality in the wider Empire, a hypothesis that gives substantial unity to the whole suburbium. Accordingly, all Constantine did was follow the Roman example of the transformation of the complex of Saint John in the Lateran into the main seat of the bishop of Rome.

Ossius, who witnessed Maximian’s persecution leading up to the death of the five Cordobese martyrs and who, at this moment (second quarter of IV century), was perfectly able to detect the first signs of the martyrdom cult born in Rome, Jerusalem and other imperial cities (in many cases encouraged by Constantine and his closest circle (cfr. Deichmann 1993; Krautheimer 1993; Testini 1980) evidently must have welcomed the imperial donativum with the intention of transforming the architectural complex into a symbol of the triumphant Church and his own personal success, maximising his propagandistic discourse with the erection on the ruins of the amphitheatre of a (possible) martyrdom complex, whose characteristics are yet to be unveiled by our archaeological work. Indeed, although the excavations of the amphitheatre are not complete, we can already hypothesize that the architectonic complex built upon its ruins after its dismantlement, facing Cercadilla and bearing a construction technique inspired by the opus vittatum employed there , is connected to the conversion of Cercadilla from praetorium to residence of the bishop Ossius, in accordance with an idea already put forward by Marfil (2000a, 2000b and 2006) and Hidalgo (2002) -although according to the latter, Ossius took possession of the palatium built by Maximian, while the former claims that the bishop built the complex himself from the second quarter of IV century.

In other words, we encounter one of the first instances of the project which both Constantine and Ossius had started to sketch, each from his own perspective but undoubtedly in a coordinated effort: a discourse based on the communion of Church and Empire (always with Constantine as its visible leader), which was to serve as one of the ideological pillars of the new regime. Soon, however, theological disputes would throw a shadow on this (Veyne, 2008). Let us not forget how the hundredyear-old Cordobese bishop was cast into oblivion by the whole of western Christianity (Nieto, 2003, 20 ff), including his own diocese (almost a dannatio memoriae), following the confusing events that surrounded his move to Mediolanum and his consequent detention by Constantius II in 356; his presumed fall into Arian heresy (to which he had been opposed half of his life), and his immediate death in Sirmium, probably towards the end of 357 (cfr. Clerq 1954 and, more recently, Ventura 2014).

If Ossius had indeed managed to establish his Episcopal seat in Cercadilla , the above-mentioned events must have played a role in his rapid loss of prestige and perhaps caused his successors to move the seat to Saint Vincent at the end of V century or the beginning of VI, at a time when the urban network inherited from the Romans was not yet too fragmented . This would enable them to create a unitary and extensive establishment, as we have claimed before (León & Murillo 2009), in accordance with the definite disintegration of the Roman provincial administration and the configuration of the bishop and a small urban and largely ecclesiastical oligarchy as the city’s new social, political, and economic (but also religious) leaders. This happened just before the fragmentation of Hispania in 409 at the hands of Suebi, Alans and Vandals, summoned by the emperor himself in the context of the umpteenth usurpation and its consequent civil war (cfr. Arce, 1982). From then on, the mists of oblivion that had obliterated Ossius’ memory extended to Cercadilla, and the suburbium metamorphosed into a building with a largely martyrdom and funerary character, closely related to its martyr par excellence, Saint Acisclus, who continues to be associated with many of the events that took place within its walls .