I. Introduction

As a function of trade acceleration and the development of information and communication technologies, intellectual work is more vulnerable to copying and counterfeiting and collateral effects (OECD, 2007; Mendoza & Ríos, 2013). Countries have thus been forced to implement border measures aimed protecting trademarks and copyrights; these precautionary mechanisms, applied by customs in the air, maritime and land limits, provide for the suspension of customs clearance for possibly infringing goods while the competent authorities analyze the alleged violation.

However, the enforcement of intellectual property rights should under no circumstances hinder trade facilitation or cause unnecessary delays (Schmitz, 2013). In Ecuador and in the countries that form part of the Andean Community of Nations (CAN), the mechanism’s adoption causes high transaction and administrative costs in import and export operations, due to the absence of specific rules of the game (legal-economic institutions, as described by Méndez & Alosilla, 2015) and of an automated procedure (under a continuous improvement scheme that reaches beyond a command and control approach) that stimulates the active participation of owners and proxies, importers, exporters and competent authorities (SENAE and others entities responsible for command and control ). This article thus proposes a theoretical review using an economic analysis of the law applied to this mechanism’s treatment, particularly in the area of customs1.

II. Facilitation against regulation and customs control for trade

Commercial exchange implies transit between borders, whose norms and procedures-when not internationally harmonized-create on-going technical and administrative obstacles. These increase the transaction costs2 that must be borne by the operators, who in turn transfer them to the industrial and final consumer sale price (León, 2008). Delays and bureaucratic hang-ups morph into very effective barriers in restricting a product’s access to another market-even more so than tariffs-and minimize the possibility of fully exploiting the tariff reductions which are negotiated, or a possible opening of markets (Saavedra & Fossati, 2006). Trade facilitation attempts to address this concern by creating a global approach to the implementation of mechanisms to simplify the movement of goods; using infrastructure improvement and transport regulation, the use of homogeneous provisions in customs legislation, the application of Information and Communication Technologies, the flow and exchange of information, the efficient participation of both government agencies and companies intervening in foreign trade until a comprehensive customs reform is achieved (Jaimurzina, 2014).

Meza (2013) maintains that the facilitation of trade seeks the simplification and harmonization of various kinds of procedures and standards. This is focused on the provision of customs services that allow more agile flow of trade, while at the same time ensuring compliance with national legislation and guaranteeing citizen safety; as such, we are referring to a matter of facilitation versus control. On the other hand, Garrido (2009) notes that «there is no ideal world in which it is worth either not controlling or controlling everything that enters or leaves a country. It is known that both 100% and 0% of customs intervention is not an effective control». Therefore, excessive control will not contribute to facilitation, or vice versa. The presence and role taken on by different international trade-related governmental and non-governmental organizations-especially the actions undertaken by the World Trade Organization (WTO), considered the institutional framework for inter-state commercial relations, and the World Customs Organization (WCO), formed to promote inter-country cooperation and communication regarding customs matters-have a massive impact at the global level through the deployment of multiple efforts carried out independently or jointly to reduce trade barriers, lessen delays in international freight traffic, and eliminate high “transaction costs” (Meza, 2013).

The formal rules of the game regarding Trade Facilitation are global in scope, and binding for member countries. The WTO promoted negotiations for a Trade Facilitation Agreement, which concluded in December 2013 in the framework of the Bali Ministerial Conference; while the WCO developed a series of tools to guide member countries in the adoption and effective application of the Trade Facilitation Agreement, as well as implementing common standards, such as the revised Kyoto Convention and the Normative Framework for Ensuring Global Trade (SAFE). SAFE establishes norms to guarantee the chain’s security and to facilitate commerce under a series of standards aimed at fortifying the harmonization of requirements related to electronic information for shipments destined to the interior, exterior and transit; the use of a coherent approach to risk analysis, the fight against crime and tax policies (Olivera & Viurrarena, 2011). Also developed were the WCO Data Model3, the Columbus Program for the creation of customs capabilities4, the Mercator Program5 for technical assistance and capacity building, and the database Project Map6, among others.

Trade Facilitation offers potential benefits for both governments and employers. These advantages that go beyond the scope of tax collection. For example, the government can make better use of available resources, provide more efficient and transparent public services, and use less invasive control methods and human resource management systems that help prevent corruption. Businesspeople gain by reducing costs and delays and by having a commercial system that fights unfair trade (Roca, 2010). In this context, customs is a highly influential actor in the sphere of international trade: on the one hand, the controls it exercises ensure compliance with national legislation, fair tax collection and the protection and security for the society; on the other, it must contribute to more agile trade through effective and efficient customs processes that promote economic competitiveness (Garrido, 2009). These activities must be carried out according to the treaties and international agreements thereby subscribed to. The modern, highly competitive world we face demands that countries urgently reduce bureaucracy and create scenarios that tend towards a minimization of transaction costs, and incentivize investment and business (Olson, 1996).

III. Customs control of import and export goods in ecuador

The World Customs Organization has defined “customs control” as «measures applied for the purpose of ensuring compliance with the laws and regulations for which Customs is responsible» (Revised Kyoto Convention, 1999). Chapter 6 of the International Convention for the Simplification and Harmonization of Customs Procedures, known as the Revised Kyoto Convention7 deals with the issue of customs control, and demands the effective application of intelligent controls through the implementation of risk management techniques by the members of the WCO.

At the Community level, Decision 778 defines customs control as «the set of measures adopted by the customs administration in order to ensure compliance with customs legislation or any other provisions whose application or execution is the responsibility of customs». Control is applied to the entry, storage, transfer, circulation, storage and exit of goods and means of transport, to and from the national customs territory8; it is also applied to foreign trade operators and people entering or exiting the territory.

The provisions of the WCO and the CAN refer both to control over the collection of taxes, as well as to other responsibilities for which the customs administration is responsible, derived from provisions issued by other authorities, such as vigilance over the entry or exit of products which must comply with sanitary, phytosanitary, zoo sanitary and quality standards, or merchandise that may not be imported due to its characteristics, or constitutes harmful or violate intellectual property; however, at the same time, trade should be facilitated. One modern facilitation practice is risk management, a tool that allows for a more appropriate balance to be achieved between control and facilitation. In Ecuador, three types of controls were thus introduced based on selectivity criteria and risk indicators: previous, concurrent (during the dispatch) and subsequent (ANEPI, 2014).

During the previous control, the customs administration conducts investigation or direct inspection of foreign trade operators and selected merchandise using the risk profile system. These actions are carried out prior to presentation of the customs declaration. In as much, concurrent control, or control during the dispatch, is exerted from the moment of the customs declaration presentation until prior to the release/shipment of the goods to the exterior. Finally, subsequent control includes the verification of customs declarations and investigations that start with the release/shipment of merchandise abroad (Código Orgánico de la Produccion, Comercio e. Inversiones, 2010). To carry out control, countries must use a selective, risk criteria-based method and the implementation of computer procedures that allow for adequate processing of large volumes of information (Decisión 778).

Due to the need to reduce wait times at customs, concurrent control is one of the most critical process phases; delays that arise thus hinder trade facilitation aims. For this stage, Customs uses a selective approach. This implies that once the importer or exporter turns in the customs declaration, the administration assigns a certain dispatch mode through its computer system:

Physical: there is a physical recognition of the merchandise in which nature, origin, condition, quantity, weight, measure, customs value and tariff classification are reviewed; this information is compared against the customs declaration. Said modality aims to verify the correct payment of taxes and compliance with the provisions for the entry or exit of goods from the national territory. The customs officer can remove a small number of samples of the goods in case of doubts about their nature.

Documentary: a verification of the accompanying and support documents,9 as well as the information entered in the customs declaration; no physical inspection of the merchandise is carried out.

Automatic: the system automatically carries out an electronic validation of the declaration, without subjecting it to any type of control. This type of channel can be beneficial for operators whose risk profile is quite low (COPCI, 2010).

In Ecuador, the authority in charge of carrying out control is the National Customs Service of Ecuador, an entity that has customs control as one of its primary functions. COPCI requires that, in all foreign trade operations, precise controls be applied through risk management in order to ensure compliance with the legal system and tax interests (cfr. Article 104). Customs control is applied to the entry, stay, transfer, circulation, storage and exit of goods, cargo units and means of transport to and from the national territory, including goods going into and out of the Special Economic Development Zones (cfr. Article 144).

To contribute to facilitation and effective control, in 2012 Ecuador implemented a new customs computer system called Ecuapass. This was done with the technical assistance of Korea and supported by the signing of the Framework Cooperation Agreement for the Establishment of the Electronic Dispatch Customs System in the Republic of Ecuador in October 2010 (Martínez, 2014), between the Ecuadorian Customs Corporation (now SENAE) and the Korean Customs Service, with the approval of the President of the Republic of Ecuador. Korea uses a paperless customs system known as UNI-Pass, considered the fastest among the WTO member countries.

In March of that same year, the government issued Executive Decree 285, through which it declared the Single Window (Ventanilla Única) as part of the foreign trade policy and national strategy for procedure simplification. This tool creates interconnection and participation among all customs service users and all foreign trade operators, as well as public entities related to foreign trade. According to Article 1 of said Decree, users of the customs service shall «(…) present the requirements, procedures and documents necessary to carry out foreign trade operations (…)» through the single window. (Decreto Ejecutivo 285). The single window design was used in the Ecuapass system10.

The project’s economic cost was approximately 21.6 million dollars, while the State invested around 15.8 million dollars for the Single Window (Rosales, 2011). Why, however, was the decision made to replace SICE (Sistema Integrado de Comprobantes Electrónicos)? This system, implemented in 2003 by the former Ecuadorian Customs Corporation, allowed customs procedures to be systematized and streamlined for a period of nine years; however, its limited flexibility quickly made the system-which based its operation on the excessive paper use and delayed customs processes and procedures-obsolete. Mediavilla (2013) points out that this situation caused around 13 million dollars in losses for the approximately thirty thousand foreign trade operators who used the system.

Ecuapass introduced the “zero paper” instrument in Ecuador, which seeks to minimize the use of paper in procedures. It promotes the Single Window and the use of an electronic signature as a safe means for processes and seeks a more efficient version of customs control that does not hinder trade facilitation. This is done through high-level risk management which capable of detecting risk factors thanks to feedback from and continuous accumulation of data generated by foreign trade operators (Mediavilla, 2013).

But what is the link between customs issues, trade facilitation and intellectual property? Customs play an important role in the defense of intellectual property rights in international trade (Ibañez, 2013); the role of customs should consist of the effective exercise of control in international traffic of goods while at the same time avoiding delays that entail transaction overruns for importers or exporters (Olivera & Viurrarena, 2011). Although customs’ main mission has historically been the collection of taxes on foreign trade, this function has changed thanks to the advance of international trade and regional integration, driven by accelerated globalization processes and the intensification of competition (Loucel, 2012). The customs administration’s work has thus expanded, and its role is increasingly decisive in countries’ economic existence and in commercial exchange. Báscones (2008) notes that a current consensus exists which views customs’ objective as a tax collector as purely auxiliary and complementary. At present, customs plays an essential role in applying standards that seek to protect trade-related intellectual property and environmental rights, combat new threats to State security, smuggling, drug trafficking, etc. (Garrido, 2009), in addition to its task of facilitating trade.

During the concurrent control stage, customs must take the necessary actions to prevent the entry of products that infringe IP (Intellectual Property) rights on trade routes, specifically when they violate trademark rights. Thus are the so-called border measures adopted.

IV. Border measures: criminal scope and unfair competition

Border measures are key because of their ability to create significant obstacles to free trade. Otero (2012, p. 539) defines these measures as «(…) the actions taken by the customs authorities on the goods under their control (…)». They are designed to intercept infringing goods that are entering or exiting the domestic market-even those acquired on the internet and sent using postal services. They are, therefore, temporary measures that can only be applied at the border, when the goods have yet to be released from customs.

The adoption of border measures can, at times, represent a technical obstacle to normal and recurrent trade; however, they cannot be ignored by the WTO members, as they were implemented through the agreement of Trade Related Aspects of IP Rights (TRIPS).

The TRIPS Agreement includes mechanisms designed to confront and control unfair competition, which affects trade and discourages innovation. Albán (2013, p. 194) points out that «(...) experience has shown that there is very little chance that fair competition will be established simply by letting market forces interact (...)».

However, TRIPS limits the scope of these measures solely to the control of merchandise bearing false trademarks and to pirates that damage copyright. The customs authorities must thereby suspend import operation at the request of SENADI or of the rights holder until the competent authority determines if the intellectual property rights are indeed violated; except in the case of insignificant amounts (Articles 51, 52, 58 and 60). This means that other IP rights will receive protection through other civil, criminal or administrative measures, once they obtain the status of nationalized goods; that is, after they have been subjected to all the customs formalities corresponding to the importation for consumption and they are in the Ecuadorian commercial circuits (Triana, 2010).

IV.1. Sanctions in Criminal Matters in Ecuador

In Ecuador, trademark counterfeiting is one of the most recurrent problems in the area of IP rights infringement; products such as clothing, footwear, perfumes and cosmetics, personal grooming, household use, food and non-alcoholic and alcoholic beverages, pharmaceutical products, tobacco, chemicals and pesticides have been the object of this type of infraction. In 2015 alone, SENAE adopted approximately 205 border measures in the country11.

While around 85% of the cultural goods purchased in the local market are pirated, causing authors and industries large losses due to the high transaction costs incurred in bringing their works to the market. The piracy of software, DVDs and CDs costs the country almost ten million dollars in direct and regressive taxes; the material used for this activity comes from Peru and Colombia (Calvache, 2016). Although there are no official figures on piracy, it is estimated that 99% of films and 95% of musical works sold in Ecuador are pirated.

The problem is that the Ecuadorian State itself protects this illegal activity. Although since 2011, the government has carried controls to reduce so-called “cachinerías”, it has also regularized sellers of pirated music and movies. In that year, approximately 2816 commercial premises dedicated to the sale of illegal discs and DVDs were registered in the Internal Revenue Service (SRI), which implies that these sites operate with all permits required by the authorities under the name of “lucrative formal piracy” (El Universo, 2011). At present, there is no exact data regarding the number of businesses operating locally. However, the ASECOPAC (2011) calculates there to be at least 60.000.

Protection of IP rights is therefore quite weak and scarce in Ecuador, as evidenced by regulations in the criminal field. The criminal provisions linked to intellectual property rights were repealed in 2014 with the new Comprehensive Criminal Code (COIP) through the 22nd derogatory provision, which stated: «Repeal Articles 319 to 331 (...) of the Codification of the Law of Intellectual Property (…)»; that is, the entire chapter II on crimes and penalties. This situation further clouded Ecuador’s image before the international community, to such an extent that, in 2015, the Office of Foreign Trade of the United States (USTR in English), included Ecuador within its “Priority Watch List”12.

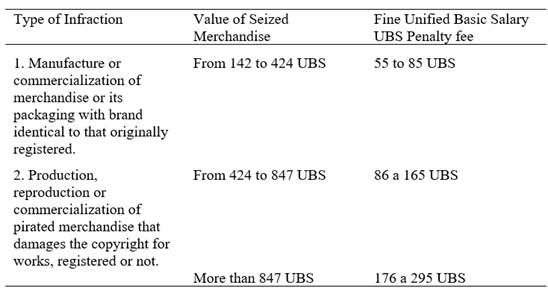

Ecuador is not characterized by the implementation of efficient controls against trademark counterfeiting or the import and consumption of these products (Rodríguez, 2014). In fact, the negotiations of the Multiparty Agreement with the European Union and the country’s inclusion on the Priority Watch List of the United States, were the starting point for the country to return to regulations regarding criminal sanctions for this activity. In August 2015, the National Assembly approved, in the second debate, the Organic Law for Reform of the COIP, by means of which several crimes were typified, among them: trademark falsification and copyright piracy; however, only economic fines were established, and prison was eliminated. Such reforms came into effect as of September 30, 2015 (see Table 1).

The reforms establish, among other things, that the penalties to sanction IP infractions will not be applied when: (i) The goods or products do not have a commercial purpose; and, (ii) The imitation merchandise fabricated or commercialized has a brand with its own characteristics that do not lead to confusion with the original brand, without prejudice to the civil liabilities that may arise (Metro Ecuador, 2015).

Table 1: Fines established in COIP reforms, in 2015

Source: Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador. Elaborated by the authors

Note: In Table 1 (sections 1 and 2) any copy made without the right holder’s consent. When dealing with well-known or high-profile trademarks, it is not necessary that the trademark be registered in the country to prosecute the infringement. Also, in Table 1 (sections 1 and 2) the aforementioned economic sanctions do not apply to cases presented during the application of border measures, but rather in regard to illegal activities that are carried out within the Ecuadorian territory. Finally, the Unified Basic Salary of the worker in general is named as “UBS”.

Once the measure has been adopted, SENADI is the only institution competent to determine whether the subject of the controversy violates the IP rights. If an infraction is detected, this institution is in charge of administratively sanctioning the offender through a motivated resolution with a fine of between 1.5 UBS up to 142 UBS considering the infraction’s nature, as well as ordering the adoption of one of the precautionary measures established in Section II, Article 565 of the Code of Ingenuity or confirming those of provisional character-among the most important of which is the merchandise’s apprehension and destruction. It is therefore evident that penal sanctions are not applied for infractions detected as a result of the application of border measures.

IV.2. Provisions Regarding Unfair Competition

Unfair competition affects not only direct competitors-It also has impact on indirect competitors and consumers. The general clause (Article 10 bis) of the Paris Convention (1883) for the Protection of Industrial Property states that «any act of competition contrary to honest practices in industrial or commercial matters constitutes an act of unfair competition». The acts typified as illustrative as disloyal are: confusion, cheating and denigration. These facts, acts or practices must be prohibited despite being unconscious acts without harmful effects to the competitor, consumer or the economic order: that is, the simple threat of harm constitutes unfair competition.

In Ecuador, unfair competition is defined in the Organic Law of Regulation and Control of Market Power (Ley Orgánica de Regulación y Control del Poder de Mercado). In this regard, said Law considers as unfair «any act or practice contrary to honest customs or practices in the development of economic activities, including those conducted in or through advertising activity» (Article 25). Economic activities include commercial activities, professionals (lawyers, doctors, engineers, etc.), services, etc. The control of acts or practices such as confusion, deception, imitation, denigration, comparison, exploitation of another’s reputation, violation of business secrets, contractual infringement, violation of norms, harassment, coercion and undue influence against consumers, among others, is overseen by SENADI and the Superintendency of Regulation and Control of Market Power.

In the case of SENADI, it may order the adoption of border measures as precautionary measures adopted prior to the entry of merchandise into the Ecuadorian market; that is, at land, sea or air borders. This is not so in the case of the Superintendency of Regulation and Control of Market Power, whose action is limited to controlling the restrictive commercial practices of free competition and unfair competition, such as, for example, the abuse of intellectual property rights that lead to monopolistic practices, or the impact caused to a natural or juridical person by the falsification and piracy of goods in commercial circuits (in the national market)13.

V. Impact on transaction costs in import and export operations

While experience in this field is not transcendental, some countries have begun to adopt these types of measures. One possible cause for the recent attention is that the TRIPS Agreement has not issued uniform criteria on how measures should be applied and has given too much freedom to member countries to establish a method or procedure that is appropriate according to their legal practice (Ponce, 2001). In the case of Ecuador, the procedure was understood to start and end at Customs (for cases in which it is lifted) (Triana, 2010). It does not necessarily contribute to the achievement of trade facilitation objectives (if the intermediate process to be carried out is taken into account), which include: reduction of transaction costs-since there is no positive interaction or point of balance between Trade Facilitation and customs control-; benefits all foreign trade operators; and an extension that includes all brand owners (CAN, 2007). When high transaction costs occur, losses in time and money are generated by delays and extra charges, imports become more expensive, and consequently, the good’s price on the local market increases.

Transaction costs is a term that appears in the organizational field (Alonso & Garcimartín, 2008) thanks to economist and Nobel laureate Ronald H. Coase (1998, p. 73), who links it closely with economic exchange:

A human society’s welfare depends on the flow of goods and services, and this in turn depends on the economic system’s productivity. Adam Smith explained that this productivity depends on specialization (...), but specialization is only possible if there is exchange - and the lower the exchange cost (transaction costs, if desired), the higher the system specialization and productivity. However, exchange costs depend on a country’s institutions: its legal system, its political system, its social system, its educational system, its culture, etc. Indeed, it is institutions that govern economic functioning (…).

Institutions or rules of the game are designed to simplify and reduce transaction costs. For San Emeterio (2006), the State and businesses are two of the main institutions. The State as an institution reduces the costs of defining and applying rights exchanged on the market; therefore, it oversees protection of property rights. North (1993) argues that the creation of institutions related to the defense of property rights, especially intellectual property rights, is one of the central factors explaining the path of capitalism and progress followed by certain Western societies; that is, he believes that the creation of institutions improves a society’s degree of efficiency (cfr. Alonso & Garcimartín, 2008).

Therefore, when talking about transaction costs we refer to the cost which we incur to carry out an economic exchange: that is, the cost of each market operation. The importer or exporter incurs exchange costs in all phases of its activity: customs costs, transportation costs, certification costs, non-tariff document costs, storage costs, demotion costs, among others (Zamora & Navarro, 2015); i.e., the trade costs, which can be either direct or indirect. Direct costs derive from complying with cumbersome customs procedures and gathering all information and documentation required, while indirect costs are linked to inefficient procedures that involve delays at the border, cause the loss of business opportunities, and generate depreciation costs (in the case of perishable products) and inventory costs (Jordán, 2008).

León (2008) explains that trade costs can be grouped into two categories: (i) Costs derived from trade policies: barriers to market access (Tariff and non-tariff barriers); and, (ii) Costs derived from the business environment: transportation costs (these include freight costs), information costs, contract compliance, derivatives of currency conversion, regulatory costs and costs associated with internal asset distribution (wholesale and retail sale).

The second group of costs can affect the performance of companies’ or individuals’ activities due to institutional obstacles (in transportation, regulation, logistics and physical and technological infrastructure) and due to information asymmetry and the bureaucratic presence throughout the chain of official procedures required for the import or export of goods or services (León, 2008). These excessive business environment barriers make imports more expensive. Hence, the instruments and policies that encourage the creation of an institutional framework reinforcing property rights, the promotion of free access to information and the development of physical and technological infrastructure take on more importance than trade policy-related instruments and policies.

Within this category are costs derived from the application of border measures (Merchán & Molina, 2013).

Though the institutions or rules of the game are created with the objective of simplifying and reducing transaction costs, the latter undergo a significant increase when rules are not sufficiently clear and specific (information costs); that is, the more stages present within a given procedure, the higher the costs. The time used to apply a procedure plus the amount of information is equivalent to the transaction cost; therefore, the less information, the greater the times and costs. In the case of border measures, evidence has shown exaggerated times following the physical assessment and the measure was adopted until the former Instituto Ecuatoriano de la Propiedad Intelectual, IEPI (currently Servicio Nacional de Derechos Intelectuales, SENADI) issued the resolution (control cost losses); this added to scarce information on the subject and the ignorance of foreign trade operators-aspects that negatively impact foreign trade operations, particularly imports.

This impact is mainly due to the extra charges incurred by the importer when the time for the release of the customs goods exceeds that projected, and directly affects the budget assigned to the importation of said merchandise. The following items are included in the import cost14:

1. Value of the goods;

2. Foreign Currency Exit Tax;

3. Freight and local expenses payable to the international carrier;

4. Merchandise insurance;

5. Taxes on foreign trade (Ad-valorem, FODINFA, Safeguard)15;

6. Customs Agent Services;

7. Merchandise storage in Customs warehouses; and,

8. Local transportation (from the port or airport of arrival to the importer’s warehouse).

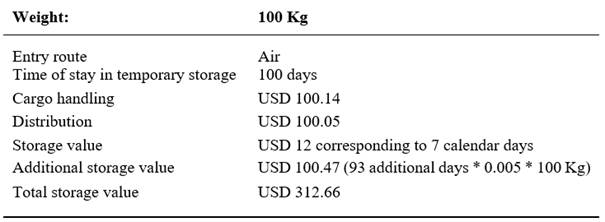

The items primarily affected by the adoption of a border measure are storage and expenses payable to the international carrier. The storage fees for goods entering by air are established based on cargo weight. This cargo may remain for up to seven calendar days. From the eighth day on, the temporary storage deposit charges the basic rate plus USD 0.005 per additional calendar day, per kilo of cargo or fraction thereof; for cargo requiring a cold room the rate is USD 10.00 from 0 to 100 kilos and USD 15.00 for 101 kilos and up. For shipping, the storage rate for a container is between USD 3.26 to 5.22 per day; and general cargo between 0.26 to 0.52 cents per day. For a better understanding, the following example is given:

Table 2: Example Administrative Cost Calculation (storage)

Source: COIMPEXA. Elaborated by the authors

This table shows a significant increase in storage costs due to the additional days that the merchandise must remain in the temporary customs warehouse. This results from the adoption of border measures and a late response from the former IEPI (SENADI). The average time for customs clearance of non-perishable goods is less than five days (SENAE, 2018).

The administrative cost caused by overstay or delay must be paid by the importer when the empty container has not been returned within the days granted by the shipping line (days open for the container lease: generally, eight days for import and seven days for export). Once the term expires, the airline establishes the payment of a fine for failure to return the container. This value varies according to container size and the days of overstay, from USD 75 to 135 for import and USD 25 to 40 for export for each day of delay.

The old Intellectual Property Law did not provide for a protection mechanism for the importer and exporter when adopting border measures; thus, when a border measure was lifted after the established time, importers had to bear excessive administrative costs that affected the import cost and therefore the import factor16, to which a desired profit margin is added to finally obtain the consumer sale price. The new Inventions Code (Código Ingenios), in Article 578, accept the possibility of establishing a SENADI deposit for the adoption of precautionary measures to protect the importer or exporter and prevent possible rights abuses17. However, as with the old Law, the new Code does not define amounts or procedures. The existence of other customs clearance time related-costs thus continues to affect both imports and exports; when this process drags on for months and even years, it may cause deterioration of the merchandise and loss of business abroad or locally.

V.1. Comparison between national standards and procedures and European Community regulations and procedures

Unlike Ecuador, which lacks a special institutional framework to regulate the border measure mechanism, the European Union has two important institutions that regulate the application of border measures in the member states: Regulation (EC) 1383/2003 of July 22, 2003, and Regulation 1891/2004 of October 21, 2014 relating to the intervention of the customs authorities in cases of goods suspected of violating certain intellectual property rights and the measures that must be taken regarding goods that violate these rights.

This institutional framework establishes common rules of the game in order to prohibit transshipment, release for free circulation, export, re-exportation and inclusion in a suspension regime, free zone or free warehouse, of goods that infringe upon an intellectual property right. Among these are: counterfeit and pirated goods, and those that infringe on a patent, a complementary protection certificate, a national protection title for plant varieties, appellations of origin or geographical indications. These institutions’ aim is to deal effectively with the illegal marketing of such merchandise, without impeding the freedom of legitimate commerce (Bernal, 2010). Member States of the European Union must exclude non-commercial goods from the scope of border measures. These goods fall within the limits set for the granting of a customs exemption18: they are contained in travelers’ personal luggage and are therefore not part of commercial traffic.

The European Union rules do not explicitly outline one procedure at the request of an interested party, and another ex officio. However, the customs authority can be understood to act ex officio when in the course of customs control, suspecting that a good violates an IP rights, release is suspended or said goods are retained and the rights holder and the declarant are notified. Within three working days following this notification, the owner must submit a request for intervention, as provided by Regulation (EC) 1383/2003 (the above is under the protection of the indicated regulation).

The following describes the procedure applied in the European Union in accordance with the current provisions of Regulation (EC) 1383 (2003).

(i) Application for intervention by the customs authority: the rights holder can request customs intervention; the written request must contain all the elements necessary to enable the authorities to easily recognize the infringing goods, in particular: a) technical, precise and detailed description of the goods; b) precise data on the type or trends of fraud, if the rights holder is aware of these; and, c) contact information for the contact person designated by the rights holder.

The request must be accompanied by a declaration from the rights holder with an acceptance of responsibility should no violation be determined; the rights holder must likewise commit to covering all expenses incurred by adoption of the measure.

(ii) Acceptance of the request: The competent customs office must process and approve the request within 30 working days and the intervention will not exceed a year following the request’s acceptance. This period may be extended, however. The customs authority will not provide any compensation to the rights holder if the goods cannot be found during customs control.

(iii) Intervention of the customs authority and the competent authority to decide on merits: the national provisions in force in each Member State in the territory in which the infringing goods are presented shall apply. With the agreement of the rights holder, each EU member can use a simplified procedure. This allows the customs authorities to order the abandonment of the goods for destruction by customs control, without the need to determine whether a IP rights has been violated.

(iv) Measures applicable to infringing goods: once the infraction has been determined, the goods can be: a) destroyed; b) subject to any other measure whose effect is to deprive the interested persons of their economic benefit; and, c) abandoned to the public treasury.

Regulation 1891/2004, introduces additional provisions to Regulation 1383: the procedure for the release or retention of perishable products must be initiated as a priority over other types of products which are the subject of an intervention request; on a quarterly basis Member States are required to submit a list to the European Commission by product type, with detailed information on the cases in which the measure was adopted, including the name of the rights holder, merchandise, origin, destination, type of right violated, number of units subject to the suspension, means of transport used, and if the mechanism was applied at the request of the interested party or ex officio, in the case of commercial or passenger traffic. At the end of each year each Member State must also submit a list of the set of written requests submitted for adoption of the measure, including those not accepted. This list must contain the name of the rights holder, type of right and a succinct product description.

In Ecuador, neither similar institutionally established provisions (in terms of impact and consequence) nor a database administered by the customs authority which would have similar levels of efficiency and effectiveness have been introduced.

Table 3: Different rules of the game on border measures European Union - Ecuador

| European Union | Ecuador |

|---|---|

| The European institutional framework conditions the application of the border measure to the presentation of a request for intervention by the rights holder. | The Ecuadorian institutional framework does not prioritize the ex officio mechanism and thus most of the responsibility falls on rights holders (a). |

| Submission of a declaration by the applicant is required, in which the applicant accepts their responsibility towards the people affected by a potentially unfounded customs intervention, as well as their commitment to cover expenses for destruction. | Request of a guarantee is left to the discretion of the competent authority. The legislation currently identifies SENADI as the entity in charge of determining the fate of the infringing merchandise (no specific mention is made of the destruction destination). The Inventions Code thus establishes that the precautionary measures contained in art. 56 shall be applied (b). |

| Following express request by the rights holder, customs may extract a sample for analysis, under the sole responsibility of the latter. | Customs must extract a sample to be sent to SENADI for analysis. This applies only when there is a request from the owner or a ruling from SENADI. |

| Priority is given to perishable products in the application of this measure. | There is no provision regarding perishable goods. |

| Customs is not responsible for compensating the rights holder in the case that no infringing merchandise is discovered during customs control. | Customs may be considered an accomplice in infringements against IP rights if the measure is not adopted at an interested party’s request. Customs must provide information to the owner, who must adequately support the request: that is, the measure will be ordered and adopted only following the presentation of sufficient evidence (c). |

| The preparation of a list of border measures, to be adopted quarterly, is required. | There is no database or statistical information on the measures adopted in the national territory. |

Source: Regulations (EC) 1383/2003 and 1891/2004. Elaborated by the authors

Notes: (a) The Intellectual Property Law, repealed on 2016, did not provide an adequate rule of the game framework. At present, no ex officio measures are applied by customs: only SENADI can make a request ex officio or at the request of the owner before the SENADI. Cfr. Art. 575 of the Inventions Code.

(b) The Code regulation catalogs border measures as precautionary measures. In addition, Art. 61 indicates: «the national authority in charges of intellectual rights matters may order that the allegedly infringing merchandise be retained and determine its destination once the products are removed from commercial channels». SENADI thus determines the infringing merchandise’s destination. The code also states that the deposit is mainly to «protect the importer or exporter and prevent possible rights abuses».

(c) It should be noted that the new code indicates nothing specific on the matter. However, Art. 572 establishes that the national authority «shall impose the same sanction as that established in Article 569 on those who unjustifiably hinder compliance with the acts, measures or inspections ordered by said authority, or fail to send the required information within the term granted». In addition, the Code establishes that: «(…) the customs authority must provide the necessary information so that the copyright or trademark holders can have detailed information regarding the merchandise entering the Ecuadorian territory through borders, ports and airports, which will serve as support for the request of a border measure before the national authority in charge of intellectual property rights (…)» (Article 577).

V.2. Comparison between national standards and procedures in Perú and Colombia

There are certain similarities-and significant differences-in the institutional framework for border measures in force in each of the Andean Community countries. However, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador and Bolivia are governed by the same institutional framework on intellectual property, through Decisions 486, 351 and 34519.

a) Border Measures in Peru

Unlike Ecuador, which does not have specific rules of the game for the application of border measures, in Peru Legislative Decree 822 (Law on copyright), Legislative Decree 1075 (Regulation approving provisions complementary to Decision 486), Legislative Decree 1092 and Supreme Decree 003-2009-EF, are the institutions granting the customs administration the legal instruments to adopt intellectual property-related controls. In addition, the General Customs Law-Legislative Decree 1053 expressly authorizes customs to order suspension of clearance for allegedly counterfeit or pirated goods (Bernal, 2010).

To comply with these provisions, the State promulgated two specific regulations for this mechanism’s application. Until 2010, INTA-IT-00.08 was the main Border Measures Instruction. As of February 2010, INTA-PE-.00.12 came into force, establishing the “Specific Procedure: Application of Border Measures” (version 1). This includes the use of National Superintendency of Customs and Tax Administration (SUNAT) computer system, allowing the entire procedure to be carried out electronically. To comply with the stipulations of the Free Trade Agreement signed with the United States, the ex officio mechanism was incorporated in Peru.

For border measure application, both at the request of the interested party and ex officio, the rights owner must register with the customs administration, through the SUNAT Voluntary Registry of Right Holders20. This request is received by the National Coordination for Customs Arrangements (INTA), in order to verify ownership and apply measures. The INTA carries out application evaluation and registration, before requesting an opinion from the National Institute for the Defense of Competition and the Protection of Intellectual Property (INDECOPI). If this opinion is favorable, the customs officer completes the registration in the SUNAT computer system. Said registration must be renewed within the first 30 calendar days of each year (INTA-PE-.00.12, 2010).

For purposes of a brief comparative analysis between the Peruvian and Ecuadorian rules of the game, the procedure applied in Peru is described as indicated by INTA-PE-.00.12:

Procedure at the Request of an Interested Party

(i) Request: the rights holder, agent or legal representative must submit a Detention Suspension Request to the SUNAT portal, through the Integrated Customs Management System - SIGAD. The application must be submitted according to the regime for which goods are destined: for example, for importation for consumption, the term will start with the numbering of the provisional declaration until prior to the release.

(ii) Insurance: for the application to be accepted, insurance must be included for a sum not less than twenty percent (20%) of the FOB value of the merchandise for which suspension is requested. In the case of perishable goods, the guarantee must be one hundred percent (100%) of the FOB value. The purpose of the insurance is to protect the defendant and prevent abuses.

(iii) Execution of the measure: suspension is made within a maximum of three working days following application presentation. The area customs officer for the applicable regime is responsible and said officer will conduct a physical examination of the goods, draw up an Act of Immobilization and register it in the Customs Crimes Management System Module SIGEDA. Once the procedure has been carried out, notification will be made to the rights owner and/or their legal representative, INDECOPI, the person responsible for the temporary deposit and/or point of arrival, the customs broker, or the owner, consignee or consignee, as applicable. The maximum suspension term is ten business days from the date of notification to the rights holder or applicant, extendable for an equal period provided that the owner has filed the infringement action/complaint.

The competent authority can carry out physical inspection of the goods in order to issue a precautionary measure if required and must communicate with SUNAT by going to “Declaration with Precautionary Measure - Border Measures” on this entity’s web portal. The designated customs official must then issue the corresponding documents to make the goods in alleged violation of IP available to the competent authority.

Ex officio procedure

The Coordination for Audit and Management of Customs Collection - IFGRA is authorized to use physical recognition to select merchandise based on information from the Voluntary Registry of Rights Holders. During physical inspection or documentary review, presumably forged, pirated or confusingly similar goods can also be selected.

Adoption of the measure occurs when the designated customs officer in the area responsible for the regime conducts a physical examination of the goods. In the case of finding certain elements, dispatch is suspended, and an Immobilization Certificate is issued, which is registered in the SIGEDA. As in the procedure at the request of an interested party, the official must notify the rights owner, the person responsible for the temporary deposit or point of arrival, the INDECOPI, the customs agent, and the importer, exporter, owner or consignee of the commodity. The owner of the right or their attorney or legal representative must demonstrate, within three business days following receipt of the notification, that the infringement action or the corresponding complaint has been filed. A file must be presented to SUNAT including the documentation demonstrating this interposition. Once the customs officer has evaluated the documentation, an extension of the suspension for ten additional business days will be provided, as appropriate.

One of the primary reasons for a lifting of the suspension is a failure by the rights owner to present the complaint or infringement action. In order to keep the goods in a primary area, the rights owner must submit the corresponding complaint. Interruption of the measure also occurs when the competent authority does not issue a precautionary measure within the above indicated time periods, or because it determines that the merchandise is not pirated, falsified or confusingly similar.

In Ecuador, the rules of the game for the application of border measures are vaguely described in the Inventions Code and in two customs procedures manuals (sample extraction and physical appraisal); this means that, for those measures are not regulated by these institutions, the CAN’s Decisions on Intellectual Property, and in some cases the TRIPS, must be consulted. One of the main differences between each country’s rules regards the channel for appraisal; in Peru it is established that, for declarations assigned to documentary review in which the existence of a IP rights infringement is presumed, the customs officer, following verification through the SUNAT Voluntary Registry, may request a physical examination; in Ecuador, however, the manuals and instructions for documentary appraisal do not indicate the existence of this possibility-or at least do not do so clearly-since they only note that if any observation is made which merits a change in dispatch mode to physical appraisal, the official in question can request said change following approval from the Office of Risk Management and Customs Arrangements (SENAE-MEE-2-2-011-V2, 2014).

In the case of Peru, INTA’s intervention throughout the procedure is transcendental. Customs officials are active participants. This begins with the registration of rights ownership, and officials also become representatives of INDECOPI, which requires that they be trained on intellectual property issues. Registration allows SUNAT to have a database on the institution’s intranet for access by the customs personnel of the Republic; this facilitates the application of border measures at any Peruvian port, airport or land border. In addition, the Peruvian institutional framework clearly establishes suspension periods, as well as the reasons for them to be lifted. Likewise, it obliges rights owners to be involved in IP protection by requiring that in either case-ex officio and at the request of an interested party-the corresponding complaint be lodged, otherwise the measure has no effect. This safeguards the rights of the importer and exporter against possible unfounded measures.

b) Border Measures in Colombia

Like Peru, Colombia regulated the application of border measures. The government of Álvaro Uribe issued Decree 4540/2006 regarding customs controls to protect intellectual property. The government decision was due to an urgent need to fulfill the provisions of several trade agreements, such as the TRIPS Agreement, as a member of the WTO; Decisions 486, 351 and 345, Law 172 of 1994, which ratified the Free Trade Agreement between Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela. Unlike Ecuador, which does not have a clear procedure, Colombia made the necessary efforts to issue clear and concrete rules of the game that align customs control with IP protection and implement the mechanism in an expeditious and effective manner, based on direct communication between the IP rights holder and the national authority (Bernal, 2010).

The border measures procedure was ordered with the issuance of Decree 4540, to request that Customs suspend customs operations of import, export and transit in the case of the suspected existence of pirated goods or those bearing a false trademark. The institutional framework empowers the Directorate of National Taxes and Customs - DIAN to prepare an intellectual property rights holder registry in order to facilitate agile communication by the customs authority. The procedure could be synthetized in:

(i) Request for suspension of the customs operation with the customs authority or directly with the competent authority in matters of intellectual property, presented by the rights owner, the federation or association representing the rights owner, legal representative or attorney-in-fact.

(ii) Processing of the request by the customs administration, which admits or rejects the request within three days following its presentation. Once the request has been reviewed, the authority orders: a) suspension of the customs operation; b) the presentation of a bank or insurance company guarantee, within five days following the disposition from the authority, equivalent to 20% of the FOB value of the merchandise, to safeguard against possible damages to the importer; in the case of perishable goods there is no grounds to suspend the operation if the defendant provides a 100% guarantee of the FOB value to insure the damages caused by the alleged violation. Suspension notification is carried out via mail or personally to the deposit, the importer, exporter or declarant.

(iii) Intervention by the competent authority, once the petitioner presents the customs guarantee (within 10 days of the request’s acceptance) and the copy of the claim before the competent judicial authority; otherwise, suspension is canceled.

In lacking specific rules on border measures, Ecuador has profound differences in comparison to the Colombian provisions. Unlike Peru, in the case of Colombia, there is no active participation by the customs official, nor is there a specific procedure for application of the ex officio mechanism.

c) Synthesis

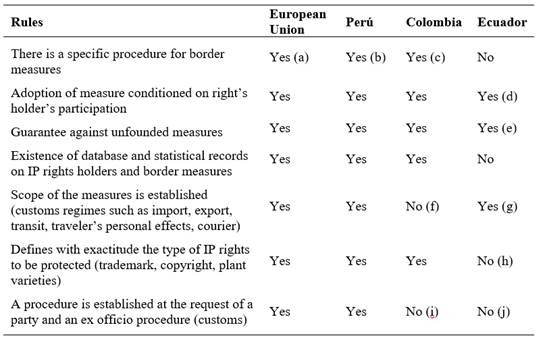

Next tables show the main differences in the rules of the game regarding border measures between the three Andean countries.

Table 4: Different rules of the game on border measures in CAN countries.

| Perú | Colombia | Ecuador |

|---|---|---|

| Establishes INTA-PE-00.12 Specific Procedure: Application of Border Measures. | Has a specific procedure regulated by Decree 4540 of 2006, by which customs controls are adopted for IP protection | Has no specific rules of the game. Some procedures are vaguely detailed in: a) Inventions Code; b) Manual for extraction of samples prior to the clearance of goods; and, c) Manual for the realization of physical capacity |

| Provides for the adoption of the measure only in the case of goods which are counterfeit, pirated or have confusingly similar trademarks, which threaten copyright-related rights or trademark rights. | Establishes how the Customs Authority will intervene in relation to the supposedly pirated or falsely trademarked merchandise. | The rules of the game provide for the application of border measures for certain types of intellectual property (copyright and trademarks). (a) |

| The rules establish a procedure at the request of an interested party and an ex officio procedure. | A clear procedure is established at the request of the interested party | There is no defined procedure for each mechanism: ex officio when ordered by SENADI, or at the request of an interested party when the owner or agent has made a duly substantiated request. |

| For the procedure at the request of an interested party, the owner and/or legal representative must request adoption of the measure before the customs authority. | For the procedure at the request of an interested party, the rights holder must request the adoption of the measure before the customs authority or the competent authority in IP. | The rights holder may request the adoption of the measure with SENADI. The new Code establishes that only the SENADI may order the measure ex officio, and therefore it is no longer customs that adopts the measure. |

| Has a Registry of Right Holders which can be accessed by all customs personnel. | The DIAN is authorized to have a periodically renewable registry or directory of IP rights holders, representatives and attorneys-in-fact. | The institutional framework makes no reference to a registry or database. |

| Specifies the customs regimes susceptible to the measure’s adoption: a) import for consumption, re-importation in the same state, temporary admission for re-export in the same state; b) final export, temporary export for re-importation in the same state; and, c) customs transit. | The Customs Authority may intervene in relation to merchandise associated with an import, export or transit operation. | Does not establish the regimes susceptible to the measure’s application. |

| It stipulates the exclusion of small items -traveler’s luggage- which will not be subject to the measure. It clearly defines that small items are those goods whose declared FOB value does not exceed USD 200. | It clearly points out exceptions: a) those subject to the traveler regime; b) those that do not constitute a commercial expedition; and, c) urgent deliveries. | The Inventions Code determines as exceptions: a) small quantities of merchandise that are not commercial in nature and are part of traveler’s luggage, and; b) merchandise sent in small batches. (b) |

| For the adoption of the measure, a guarantee is required for a certain percentage in order to protect the importer against any abuse, including perishable goods. | The guarantee is required to safeguard against possible damages to the importer, except for perishable goods, provided that the defendant provides a guarantee of 100% of the FOB value of the goods in question. | The Inventions Code states that: «The amount set should be proportional to the possible economic, commercial and social impact caused by the measure». But neither a calculation method nor a specific amount is defined. |

| Physical inspection is carried out by a designated custom official once the application has been submitted and approved, or when it is done ex officio. | The institutional framework introduces information and inspection rights, with which the IP rights holder can examine the goods prior to the request for the measure. | Physical inspection is carried out by the designated customs official either ex officio (when SENADI has ordered the adoption of the measure directly) or at the request of an interested party (when the owner of a trademark or copyright registration has sufficient evidence to assume that import or export of merchandise that injures its trademark or copyright rights is going to take place), which extracts a sample of the presumably infringing merchandise. The Inventions Code introduces the possibility that the rights owner may inspect the merchandise, following the measure’s adoption. (c) |

| Source: SUNAT, SENAE, DIAN. Elaborated by the authors |

Notes: (a) Inventions Code, Art. 575: «(…) causing injury to trademark or copyright rights (…)». Current antitrust regulations are not focused on this matter. (b) Inventions Code, Art. 583: «Small quantities of goods that are not commercial in nature and are part of travelers’ personal luggage or sent in small batches are excluded from the application of this chapter’s provisions (…)». (c) Inventions Code, Art. 579: «In order to substantiate their claims, the owner of the intellectual property rights may make a direct request the competent national authority in customs matters, which allows it to inspect the goods to be imported or exported, without prejudice to taking the measures necessary for the protection of confidential information (…)».

Currently, the TRIPS administered by the WTO, is the most important institutional framework on intellectual property rights worldwide. This agreement establishes general rules about industrial property and copyright, while, at the level of the Andean Community, Decisions 486, 351, 345 and 391 regulate this issue. For this reason, the procedure of the Andean Community member countries regarding border measures has certain similarities with the procedure applied in the European Union, but there are also differences. Below are the rules of the game they have in common:

Table 5: Comparison of different rules in CAN and European Union

Source: SUNAT, SENAE, DIAN, EU. Elaborated by the authors

Notes: (a) Regulation (EC) 1383/2003 of July 22, 2003, and Regulation 1891/2004 of 21-X-2014. (b) INTA-PE-00.12. (c) Decree 4540 of 2006. (d) Not conditioned to the owner’s necessary participation, the SENADI can request the measure ex officio, Customs can no longer adopt a measure on its own. (e) The calculation method is not established, unlike the countries with which the comparison is made. (f) Indicates only Import, Export or Transit operation. (g) Exceptions made only for small quantities of goods not of a commercial nature and are part of travelers’ personal luggage or are sent in small consignments; but the excluded customs regimes are not defined. (h) The exceptions for the application of border measures are not determined, provisions issued in the Decisions of the CAN are applied. (i) The procedure at the request of a party is clear, the ex officio is not defined with exactitude. (j) Customs can no longer take ex officio measures. In this case, only the SENADI can act ex officio or at the request of the owner, requesting Customs’ intervention for the adoption of the measure.

VI. Conclusions

1. This article has conducted a theoretical review of border measures (customs area) based on the conceptual contributions of the economic analysis of law.

2. Customs represents one of the most important agents in the field of international trade. However, a highly competitive world requires that countries, and the entities within them, cut down on bureaucratic procedures at the customs level and create scenarios aimed at minimizing transaction costs; that is, which boost investment and business through the elimination of market access barriers that could be described as irrational.

3. Ecuadorian customs, and in general customs within the CAN countries, must take the actions necessary to prevent the entry of products that infringe IP rights on trade routes, specifically when they violate trademark rights. The so-called border measures are thus adopted. In recent years Ecuador has made significant improvements to its institutional customs framework and the use of information and has implemented communication technologies such as ECUAPASS and the Single Window, whose positive effects translate into more agile customs clearance and less intervention from officials.

4. It is necessary for specific regulations, manuals and instructions to be redesigned, using a perspective that goes beyond mere command and control-that is, that the procedure for the application of border measures be defined. To this end, the law empowers SENAE and the former IEPI (SENADI) to cover the existing legal gaps. The procedure to be followed for each type of mechanism (ex officio and at the request of an interested party) must be regulated21. This includes clear guidelines on insurance, deadlines and forms for notifications, priority sectors, treatment of perishable products, and technological tools to be used, among other aspects. Procedure design can be based on the scheme proposed by countries such as Peru or the European Union, with the perspective of reducing intra-systemic transaction costs and administrative costs derived from bureaucratic action.

5. The Inventions Code eliminated the possibility for ex officio adoption of border measures by Customs; as such, this entity is unable to adopt these measures unless there is a request from the rights owner, or when the SENADI makes an ex officio order based on knowledge of an alleged violation. This demonstrates that in Ecuador, effective IP rights protection is thus affected.

In addition, the Inventions Code also introduced a provision regarding the expiration of border measures, something that was not contained in the old Intellectual Property Law:

Art. 582.- «After ten working days from the date of notification of customs operation suspension, in which the claimant has not initiated the main action or without the competent national authority having prolonged the suspension, the measure shall be lifted, and the retained goods shall be dispatched. This requirement will be considered fulfilled by initiation of an action for administrative protection, a civil action or, if applicable, a criminal proceeding, as the plaintiff so chooses (…)».