Introduction

In the last decade, counter-radicalisation, preventing radicalisation, countering violent extremism (CVE), and preventing violent extremism (PVE) have become core counter-terrorism practices.1 The need to understand the extremist ideology behind violence has always been a concern in counter-terrorism. However, the London and Madrid attacks and the emerging concern for home-grown terrorism in the early-2000s in Europe led counter-terrorism towards anticipation of violence (Schmid 2013). Counter-terrorism started inquiring more strongly into radicalisation -understood as the process that leads an individual to embrace violence (Neumann 2008, 3)- as well as how to counter it and prevent it. Furthermore, in 2013-2014, ISIL’s mobilization of foreign terrorist fighters strengthened the need to act on the ideology that may lead an individual to undergo the path of radicalisation -i.e., violent extremism (Stephens and Sieckelinck 2020).

Though in different ways, the countering (reaction) and preventing (anticipation) of radicalisation were embedded in counter-terrorism architectures all around the world following exemplary cases such as the EU 2005 Counter-Terrorism Strategy and the 2006 UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy (Schmid 2013). More recently, CVE and PVE were added to international and national strategies too, propelling a ‘globalizing effect’ of CVE and PVE policies (Kundnani and Hayes 2018). Within the European Union, for example, counter-terrorism is now based on three main pillars: prevention of radicalisation and extremism, intervention with individuals vulnerable toward extremist ideologies, and de-radicalisation (Korn 2016).

The anticipatory and preventive logics of counter-terrorism are analysed in the present article. Anticipatory logics cannot be implemented from the sole realm of countering the threat from the state-led security domain. Relying on social actors, early detection seeks allies that are better positioned to spot and prevent radicalisation and extremism. Therefore, the logic of prevention has diversified the actors and spaces of counter-terrorism. As we argue, these shifts are not scattered, and they constitute the current anticipatory architecture, a structure that has transformed counter-terrorism into a complex institutional and ideological scaffolding that is paradigmatic: it is a set of diagnoses, worldviews, and recipes to tackle extremist ideas and vulnerable individuals, that inform programs and strategies all around the world. It is also a set of norms, initiatives, international networks of practitioners, transnational cooperation initiatives, national programs, and local practices. It is this scaffolding that we unpack here.

To capture the complexities of the anticipatory architecture, we look at one specific actor, the EU Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN). RAN is a network of frontline practitioners “engaged in both preventing and countering violent extremism in all its forms and rehabilitating and reintegrating violent extremists” (RAN n.d.). At the EU level, RAN is the policy network where scholars, practitioners, and policymakers exchange knowledge and practices. The Prevent Pillar of the 2020 EU Counter-Terrorism Agenda tasks the body with “identify(ing) best practices and foster(ing) approaches of community policing and engagement to build trust with and among communities” (EU Council 2020, 8). Incorporating European specificities, RAN, as a network of counter-extremist actors from member states sharing experiences and practices, is one of those institutional frameworks that condense and disseminate the global anticipatory paradigm -i.e., the set of ideas and political worldviews on how radicalisation and extremism operate (Hall 1993). We have used RAN’s structure (its working groups and topic-oriented organization) to organize our analysis, aimed at providing a comprehensive overview of the current anticipatory architecture as it appears in recent literature.

Overall, this article systematizes recent evidence and debates on extremism prevention and its relation to EU-related policy programs, to help newcomer scholars to enter the field. In so doing, we are also contributing to the existing literature on prevention and early detection in counter-terrorism debates (see, among others, Stephens, Sieckelinck and Boutellier 2019; Onursal and Kirkpatrick 2019; Hardy 2020). Even though prevention builds upon different social and political domains, the existing literature is scattered, and inter-disciplinary dialogue is still infrequent. Moreover, these analyses tend to focus on very specific domains of this architecture. Adding to the existing literature, we aim to provide a comprehensive and systematic overview of the whole anticipatory ideational and institutional architecture while also pointing to its limits. All this architecture has proven blind in detecting other kinds of extremism such as far-right, left-wing, animal rights, or environmentalist extremism. In this sense, our paper is also opportune to the extent that PVE’s paradigm and policy structure is showing explanatory and preventive weakness regarding the far-fight extremism -e.g., the US Capitol events (2021) and the Brasilia events (2023)- and other sources of potential extremist mobilization such as conspirational groups. Therefore, the scrutiny of its logic and its implementation and the opening of a space for critical reflection on its whole structure is a much-needed reflection.

Methods and materials

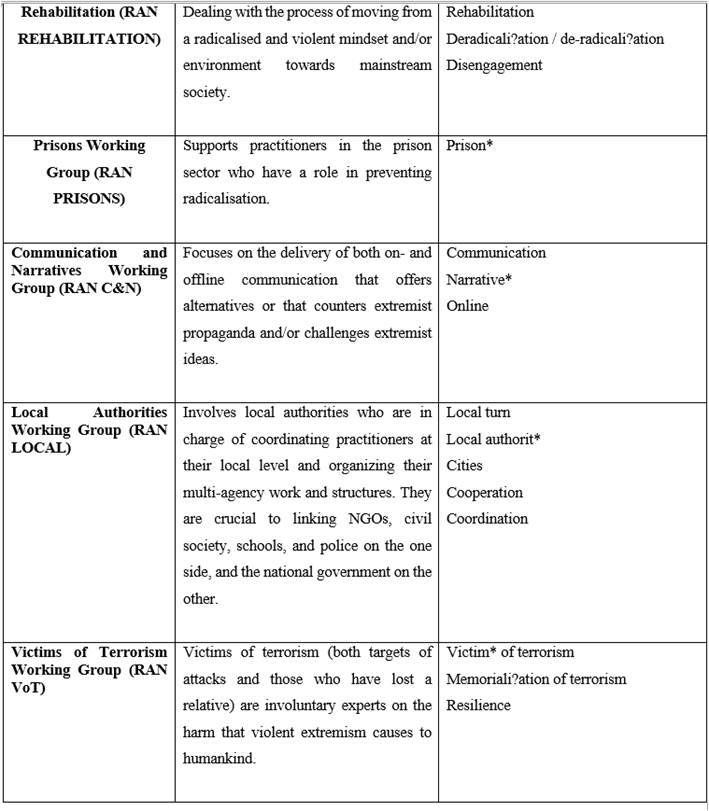

The EU RAN’s work is organized around nine Working Groups that “connect frontline practitioners from across Europe with one another, and with academics and policymakers” (RAN, n.d.). At a European Union level, we consider RAN’s structure to be exemplary of the current anticipatory architecture. Based on its Working Groups we have articulated our research (RAN n.d.). Listed in table 1, the different WGs represent the various pillars around which P/CVE is structured, and, above all, the understandings behind the implementation of P/CVE strategies (Fernández de Mosteyrín y Limón 2017). As RAN organizes its work in different spaces and actors, our revision shows the emergence of old and new actors in extremism anticipation: from the State (police and law enforcement, prisons, welfare workers) to civil society organizations such as youth, communities, victims and even private spaces such as families.

Using the WGs as categories, we have based our analysis on works examining PVE strategies in the EU. We have conducted our bibliographic research through the Web of Science using a combination of keywords representing the work of each RAN WGs combined with “PVE”, “counter*/prevent* extremism”, and “counter*/prevent* radicali?ation” (see table 1). Our primary interest was the changes wrought by the anticipatory logics of prevention. However, we also considered works dealing with countering radicalisation and extremism, as these are also underpinned by processes of early detection. The timeframe used to filter the results was 2005-2020. The year 2005 was when radicalisation and extremism started emerging with strength in the counter-terrorism paradigm (Kundnani and Hayes 2018). Moreover, to ensure a multi-disciplinary focus, we included various scientific areas -i.e., International Relations, Political Science, Anthropology, Social Psychology, Sociology, Education, and Social Sciences. We then codified and classified all the sources using the WGs as coding nodes.

Results

The results included 158 articles. A strict division per working group is difficult, as many themes overlap. However, results highlight a trend by topics (only 4 papers focused on far-right extremism while the rest centered on Islamic extremism); methodology (26 articles based on interviews, 4 on focus groups, 4 on surveys, 3 on participatory approach); and countries, illustrated in table 2 below (the rest of the paper being conceptual and theoretical discussions). The rest of the section details the specific findings.

Table 2 Results per country

| Country | n. articles | % |

|---|---|---|

| UK | 89 | 56,3% |

| Spain | 6 | 3,8% |

| Netherlands | 6 | 3,8% |

| France | 5 | 3,16% |

| Germany | 5 | 3,16% |

| Sweden | 5 | 3,16% |

| Denmark | 4 | 2,53% |

| Norway | 4 | 2,53% |

| EU | 2 | 1,27% |

| Romania | 1 | 0,63% |

| Italy | 1 | 0,63% |

| Slovenia | 1 | 0,63% |

Police and law enforcement

Police and law enforcement are the traditional pillars of state-led counter-terrorism. Nonetheless, the role of criminal justice and policing in prevention is highly debated (Hardy 2020, 1). Anticipatory needs have pushed early detection away from strictly punitive mechanisms, policing activities, or criminal justice (Weine et al. 2017). This has been in line with the implementation of “softer” preventive measures (Bjørgo 2016; Weine et al. 2017), strategies that envisage counter-terrorism as a more holistic activity embedded within society.

Within this context, police forces have also been assigned the new role of “facilitating a preventative multi/inter-agency approach at the local or regional level” (RAN n.d.). Police forces are considered to have privileged access to the community. Therefore, anticipation has included the building of trust-based relationships between police forces and communities and families to encourage the engagement and collaboration of the latter with the former in the spotting of extremism (RAN n.d.). This has given rise to formal and informal networks of cooperation at the local level (Lakhani 2020). It added a role to police forces, now representing also key nodes within networks of informants. As a result, many articles in the literature analysed refer to PVE as “policing without police”. Early detection expands, broadens, and dilatates counter-terrorism and policing power and patrolling activities. As the following section illustrates, society is called to collaborate in anticipatory efforts, a process that, however, has been highly criticized in the literature.

Families, communities, and social care

Social workers are envisaged as the privileged implementers and frontline allies to detect signs of radicalisation (Stanley, Guru and Coppock 2017). While more work is needed to understand social workers’ anticipation effort, PVE strategies securitise their work without considering their voices and expertise (Stanley 2018, 105; see, among others, Mattsson 2018).

This lack of bottom-up engagement has been problematic also because it is still unclear whether workers are sufficiently equipped to recognize potential “pre-crime” risks (van de Weert and Eijkman 2019). This situation is aggravated by the absence of clear guidelines and frameworks -or even conceptualizations- that may orient social workers in early detection (van de Weert and Eijkman 2020; 2019). Consequently, social workers need to rely on their individual perceptions rather than evidence-based criteria to identify individuals at risk in a subjective process that may thus lead to “executive arbitrariness, prejudice or stigmatization” towards a certain sub-group of the population (van de Weert and Eijkman 2019; 2020). In other words, without clear guidelines on how to recognize risk, it is feared that social workers may be influenced by the strong emphasis given to Muslim communities and individuals within European societies.

The incorporation of the “friendship/family/community” approach (Puigvert et al. 2020; Skiple 2020) was driven by the understanding that the significant others are in a privileged position to spot extremism and to enhance resilience (Stephens and Sieckelinck 2020; Thomas 2017; Spalek and Weeks 2017; Christodoulou 2020). Despite the central role resilience has been assigned in PVE, strategies based on it and the same resilience vocabulary still lack a clear conceptualization (Stephens and Sieckelinck 2020). Resilience building should include measures focused on giving individuals and communities tools to challenge extremist ideologies and shield other community members from radicalisation. Nonetheless, strategies are still far from recognizing individuals and communities not as in need of safeguarding but rather as active political actors who “require the resources and channels to challenge violence, discrimination, and injustice” (Stephens and Sieckelinck 2020; Stephens, Sieckelinck and Boutellier 2019).

Overall, the most significant and most widespread problematization of the shift towards communities has been its monocultural focus on Muslims. This somewhat contradicts the goal of community cohesion (Thomas 2010, 442). Focusing on these communities and rendering Muslims as frontline implementers was seen as a way to empower them (Thomas 2017, 4; Busher, Choudhury and Thomas 2019). However, as the literature shows, this shift resulted in the constitution of “suspect communities” and in the implementation of a “policed multiculturalism” that allows the “government of society in discrete and divided ethno-religious groups” (Ragazzi 2016, 724). Critical voices argue that these processes have involved community members in their own policing embedding infrastructures of internal surveillance and state control within these communities (Abbas 2019, 396; Qurashi 2018; Thomas 2017; Ragazzi 2016). Moreover, constructivist scholars denounce the performative nature of prevention. Seeking allies within Muslim communities, prevention identifies and constitutes those communities, singling them out within European societies (Ali 2020; Heath-Kelly 2017b; 2013). More skeptical works problematize the focus on “vulnerable Muslims” as “practices of (neoliberal) governmentality” implemented in European societies to shape Muslims into neoliberal subjects (Szczepek Reed et al. 2020; Ali 2020; Abbas 2019).

The focus on Muslim communities has been pointed out as the source of “resentment from white working-class communities” (Thomas 2009, 282), defensiveness and alienation from Muslim communities, “alienation that is detrimental to counter-terrorism efforts” (Taylor 2020, 851). Nevertheless, further research is needed on the real impact of anticipatory logics on Muslim communities as emerging findings point to divergent results. Shanaah’s surveys of British Muslims show that “only a minority shows signs of alienation and that most British Muslims are satisfied with and trust counter-terrorism policies as well as the government and the police” (Shanaah 2019). Contrastingly, other scholars’ findings point to the fact that Muslim communities denounce that the prioritization of C/PVE takes away the governmental focus on other community’s problems - such as domestic violence, community funding, etc (Winterbotham and Pearson 2016). Moreover, the prevalence of convert recruits in certain countries has cast doubts on the focus on Muslim communities and narratives linking radicalisation to failed integration (Winterbotham and Pearson 2016, 61).

Youth and education

“Youth” is among the most important concerns within PVE. Its priority is reflected by the results returned by our bibliographic research as 45% of the articles deal fully with this category. The anticipatory prioritization of youth is driven by three reasons. First, youngsters are regarded as a vulnerable group and thus, most at risk of radicalisation (Mattsson, Hammarén and Odenbring 2016; Pedersen, Vestel and Bakken 2018; Heath-Kelly 2013). Secondly, youth is understood as a well-positioned group to spot signs of radicalisation in peer-to-peer interaction, and thirdly, as a privileged group to enhance resilience (Christodoulou 2020). While further research is needed on adolescents’ understanding of violence (Pedersen, Vestel and Bakken 2018), existing results reveal that youngsters seem to support the use of violence to obtain societal change (Pedersen, Vestel and Bakken 2018; Zick, Berghan and Mokros 2020). This would hold true in the case of Muslims supporting jihadist groups such as ISIL or white German youth agreeing with some extreme right-wing attitudes (Zick, Berghan and Mokros 2020) -Zick et al. being among the few works on far-right extremism among the results. In the same vein, the literature highlights the need to envisage and produce nuanced approaches not only based on top-down logics but oriented to a grassroots level to work “with youth” -and not towards it- to build egalitarian and trustful dialogue and thus enhance youngsters’ resilience (Aiello, Puigvert and Schubert 2018).

The strong focus on youth has led PVE to shift towards spaces such as schools, universities, and education or recreation spaces - i.e., contexts where extremism can both be detected and countered through the building of resilience. Teachers, school staff, and social workers, among others, have been assigned the duty to participate in early detection and prevention because of their privileged position and relations with youngsters (Parker, Lindekilde and Gøtzsche‐Astrup 2020). However, implementing these logics within education spaces and by education professionals has been widely criticized for its securitizing effects. These strategies end up decontextualizing, individualizing extremism, and leading to the monitoring and surveillance of students. In consequence, these initiatives are perceived as “‘pedagogical injustice’ for students and teachers” (O’Donnell 2016) hence jeopardizing the relational pedagogy based on engagement with students on sensitive topics to develop their critical thinking (Sjøen and Jore 2019; Mattsson and Säljö 2018).

Counter-productive effects may also come from these strategies’ impact on students. Existing work points towards students’ limited comprehension and yet negative characterizations of policies such as the British Prevent, perceived as ineffective, inappropriate, and discriminatory (McGlynn and McDaid 2019). Muslim students perceive PVE as based on passive understandings of their agency as they feel that their political activism or even freedom of expression is limited by these strategies (McGlynn and McDaid 2019; Choudhury 2017). Moreover, the perception of PVE as discriminatory has been aggravated by the recent emphasis on teaching European and EU countries’ values, understood by some authors as strategies of neoliberal homologation (Skoczylis and Andrews 2020; O’Donnell 2016). On the side of schools, instructors denounce the securitisation of the classroom and the difficulties they experience in finding a balance between detection and encouraging open and genuine discussion and critical thinking on controversial topics - which they feel is instructors’ duty (Sjøen and Mattsson 2020; Bryan 2017). Advocating for a bottom-up approach, they ask for a stronger saying in the formulation of these strategies and even “greater respect for the professional experience and insights of teachers and subject communities” (Richardson 2015).

Health and mental health

While the concern for the terrorism-mental health nexus is not new, anticipation’s shift towards mental health and healthcare spheres merged with the understanding of “psychological vulnerability” to radicalisation and the need to safeguard “vulnerable” individuals (Coppock and McGovern 2014). Anticipatory logics are no longer based on diagnosable disorders and the prevalence of certain psychological traits among terrorist offenders (Augestad Knudsen 2020) but on the need to detect “vulnerable” subject - an understanding that has led to the pathologization of vulnerability (Augestad Knudsen 2020; O’Donnell 2016).

Some scholars contend that health is a privileged sphere to prevent violent extremism because of the large amount of contact these sectors have with the public (Weine et al. 2017). However, some others warn about the extension of counter-radicalization practices into the health and mental health spheres and render practitioners as first-line implementers (Heath-Kelly 2017a; Chivers 2018). Critical voices argue that this expands practitioners’ risk work and has a securitising impact on the patient-practitioner relation based on freedom of expression (Chivers 2018, 81; Heath-Kelly and Strausz 2018; Heath-Kelly 2017a). Similar to previous spheres, while research engaging with practitioners’ experience is still scarce, the existing research emphasizes the lack of clear guidelines and conceptualizations rendering practitioners’ implementation of PVE even more challenging.

Finally, some works criticize this practice as a tactic of surveillance of the population (Heath-Kelly 2017a; Younis 2020). Heath-Kelly emphasizes how, in countries such as the UK, where the implementation of PVE through health and mental care is strong, prevention has become “individualized” (Heath-Kelly 2017a). These processes are distancing anticipation from the early logics of the “suspect communities” and focus on individuals within the wider society. Even more critically, Yunis adds that the psychologisation of extremism and radicalisation may also function as a management technique of Muslim political agency and as a nation-state’s management of dissent - thus displaying lines of institutional racism (Younis 2020).

Prisons

Prisons are not new as spaces for counter-terrorism and they have always been considered settings for the exchange of information, joining groups, and radicalisation. Not surprisingly, prisons have been among the first spaces where programs for countering and preventing radicalisation were implemented. However, research in this specific field is still scattered and very few were the works dealing with this topic - produced specifically in countries with strong counter-terrorism strategies such as the UK (Marsden 2015; Butler 2020) and Spain (Trujillo et al. 2009).

The overall understanding is that the imprisonment of terrorists and potential perpetrators may reinforce radicalisation. Nonetheless, evidence in the literature points towards contradictory dynamics and different results. In fact, while radicalisation into Jihadism seems to be reinforced in prisons (Trujillo et al. 2009) this does not seem to be the case for domestic terrorism (Bove and Böhmelt 2020). Nevertheless, as said, this is one of the spaces that need further research on prisoners’ dynamics of radicalisation and frontline practitioners’ experience.

Rehabilitation

De-radicalisation, rehabilitation, and disengagement programs have been present in counter-terrorism efforts since the 1970s. However, recently they have undergone significant changes in line with anticipatory logics. These programs are now implemented in some social spheres too. Some of these strategies are no longer centrally controlled. Now, they encompass civil society organizations and are “characterized by participative and cooperative structures” (Korn 2016; Baaken et al. 2020).

Here too, the literature problematizes the important gaps in the public knowledge about these programs, the type of individuals they address, and the implementers’ role and resources assigned (see for example, Thornton and Bouhana 2019; Baaken et al. 2020; Schuurman and Bakker 2016; Horgan and Braddock 2010). Reflected in disagreements among key stakeholders and scholars, the conceptual confusion and difficulties in differentiating terms such as rehabilitation, de-radicalisation, and disengagement (Baaken et al. 2020) resulted in confused guidelines for implementers and difficulties in implementing these programs.

In a context where clear guidelines are missing and implementers are not given a strong voice in the formulation of policies, frontline practitioners work through a non-standardized -and, at times, inevitably subjective- calculation of risk about an “unknowable future” (Martin 2020; Pettinger 2020; 2021; Dresser 2019). On this, the most critical voices argue that having no clear guidelines, implementers need to interpret signs and indicators of (de)radicalisation and certain identities may be perceived as more threatening or, at least, more at risk. In other words, indicators are argued to constitute the “visible” vulnerable individuals to be intervened in a production that may be subjective and political (Martin 2020; Pettinger 2020; 2021). Acting on certain identities and ideas, de-radicalisation has been defined by the most skeptical literature as a “technology of the Self” (Elshimi 2015), a policy that works within a wider logic of governmentality of the population - something further discussed below. Lastly, the gender-blinded nature of these programs results in the failure to address women’s processes of radicalisation and their actions within terrorist groups - which may lead to downplaying women’s importance in fostering violence (Schmidt 2020; Gielen 2018).

Communication and narratives

The formulation of counternarratives and communication strategies that can challenge terrorist narratives is a key part of prevention strategies (Braddock and Horgan 2016; Frischlich et al. 2019) but also of counter-terrorism as a whole (Glazzard and Reed 2020). Strategic communication is not only effective for the prevention of radicalisation. Good communication strategies may disrupt attack planning and mitigate terrorist attack detection (Parker et al. 2019). Moreover, communication is crucial to inform society and implementers about their role in early detection (Parker et al. 2019).

The existing literature highlights the lack of comprehensive guidelines on how to develop and distribute counternarratives to effectively reduce support for terrorism, but some of the results returned from our research contribute to their formulation (see, for example, Braddock and Horgan 2016). So far, these strategies have failed in implementing a strong interactive, participative, and networked approach, problematically hindering dissemination and even trust and credibility in the source (Braddock and Morrison 2020). Moreover, the narrow focus on terrorism and (Islamic) violent extremism rather than on broader community concerns and priorities has resulted in rejection from its targeted audience (Bilazarian 2020, 46). Another problem has been the failure in creating strong synergies between offline and online communication of counter-narratives - spheres that mutually reinforce each other (Bilazarian 2020). In fact, the internet is recognized as a role facilitator for socialization into extremist thinking and learning but processes of radicalisation seem to be taking place rather in small-group dynamics and not through mass persuasion (Hamid 2020) - hence, the importance of an online and offline strategic synergy.

Local authorities

In the EU, the formulation of prevention and early detection strategies is envisaged as a dialogical process where bottom-up and top-down approaches meet and merge - for example, in spaces like RAN. The formulation of policies is then transnationally exported/imported into EU countries where it is adapted and shaped by national socio-political contexts. However, the UE’s multilateral governance is constantly challenged by national policy-making (Hegemann and Kahl 2018) and political disputes (Thomas 2017). Moreover, domestically, working at a grassroots level has not translated into national standardized approaches. So far, the focus in many EU countries has been on “priority cities” and “priority areas” considered to be hot-beds of radicalisation (see, among others, Silverman 2017; Mattsson 2019). Focusing on priority areas has allowed the targeting of resources but it has also resulted in counterproductive polarising effects on communities (Silverman 2017, 1101; Mattsson 2019). More critical voices claim that this “urban geopolitics of danger” (Saberi 2019) represents the PVE’s incorporation of processes of urban governance and policing of the population (Johansen 2020).

Locally, the implementation through and by society has given rise to formal and informal networks of relationships of trust both within social spaces such as schools and colleges and externally with public-sector agencies (Lakhani 2020). Collaboration between Muslim and non-Muslim organizations and communities is still low, but social actors and practitioners have established formal and informal networks with local authorities and local police forces - enhancing PVE (Lakhani 2020). Nevertheless, critical voices in the literature emphasize that, at a local level, prevention has also diffused the formal and informal policing and surveillance of the population (Johansen 2020).

Victims of terrorism

Victims of terrorism are key in the creation of resilience and strong counter-narratives (Lynch and Argomaniz 2017). RAN acknowledges that “victims of terrorism […] are involuntary experts on the harm and suffering caused by violent extremism” (RAN, n.d.) and inscribes them within C/PVE. Their role as survivors gives them moral authority as spokespeople for counter-narratives and de-escalation (Lynch and Argomaniz 2017). In fact, the memorialisation of victims, and the construction and maintenance of collective memory - both of the violent past but also the defeat of previous terrorist groups - are crucial elements in the formulation of counter-narratives, strategic communication, and the creation of broad societal resilience. This has been observable specifically in countries with a strong history of terrorism, e.g., Spain, where victims have come together in organizations involved in political activism for the termination of violence and have significant influence in the formulation of counter-terrorism and preventions policies (Alonso 2017; Muro 2015).

Discussion

The purpose of the present article was to present a state of the art and systematization of the main debates on how to prevent contemporary violent extremism. In so doing, we also wanted to clarify the paradigmatic architecture -both in terms of ideas on how to prevent and in terms of actors enlisted in the early-detection and preventive policy framework. Using RAN’s architecture to structure our analysis, we have highlighted the ideational landscape and institutional inscription of this set of policy programs and agencies in Europe (and around the world). Approaching C/PVE as such has allowed us to describe its characteristics as they appear in the literature, and to decipher some of its limitations. The current preventive architecture is globally shared, regionally specific, and nationally particular. A part of it is centralized to the extent that it is state-driven and implemented in state-controlled domains or public spheres. Nevertheless, it is also decentralized to the extent that society and private individuals are mobilized and called to participate in early detection and prevention, giving rise to formal and informal networks of collaboration. C/PVE goes well beyond the sphere of State policing, military and intelligence, and traditional spheres of counter-terrorism. Security forces are sided by other actors, and society and the welfare apparatus are mobilized. Traditional powers are called to provide for other roles too and the social sphere is included in prevention strategies that now include public/private partnerships, organized civil society (e.g., charities, victims associations, etc), communities, and even single individuals. Therefore, the terrorism prevention system is established as a multi-actor project state-driven and socially embedded. This move is in line with neoliberal processes of transformation of the state and reflects a logic of de-responsibilization of the state. To some extent, social actors are tasked with their protection, and responsible for their successes and failures.

Overall, however, the preventive architecture is problematic well beyond what mentioned so far. Many spheres are still understudied and further research and policy-making are needed to address them. So far, the current preventive structure lacks a stronger engagement with practitioners and bottom-up approaches. This should be studied with a view that could keep into consideration the transposition of paradigmatic policies all around EU countries. The adaptation into national socio-political contexts needs to be further scrutinized to understand how these policies can and should travel.

This structure has been at the center of the shift in counter-terrorism for the last two decades. There is significant and well-funded research underpinning it. Still, the architecture shows the weaknesses mentioned, first of all, the lack of a clear designation and conceptualization of the objects it addresses - i.e., extremism and radicalisation. At the moment, the strict focus on Islamic extremism results in several pitfalls, as seen. However, the architecture is mostly blind toward other sources of extremism. The transposition of this scaffolding to other sources of extremisms, such as conspirational or far-right is not even possible. This becomes visible when looking at RAN too. In the RAN’s overview, a wide variety of sources of extremism are identified - religious, far-right and left-wing, animal rights, environmental extremism, and, more recently, conspirational. However, these different sources of extremism fall entirely on the side of this structure and outside of any kind of early prevention and detection.

What signs of radicalisation would practitioners need to decipher in order to report extremist risk in these other cases? What would be the vulnerable community when tackling, for example, far-right or extreme-left radicalisation? What does de-radicalisation loos like in the case of environmental extremism? Are instructors prepared and well equipped to respond to conspirational extremism, which seems to be on the rise? The current framework is highly problematic when applied to Islamic-inspired extremism but it applicable to the other sources mentioned. As it stands, it would be impossible to develop an efficient policy to deal with these other extremisms or, at least one that would not clash with human rights. It is this hinge that our paper wished to break.