1. Introduction

The issue of “constitutional identity” is a topic which has already certainly attracted multi-layered approaches, and which may have similar relevance in contemporary constitutional democracies as far as constitutional changes are concerned. In this article, I have chosen a legal approach to studying the “constitutional or national identity”, because, via Article 4.2 of the Treaty on European Union (from now on TEU), it became a legal phenomenon requiring the EU not to infringe it. That is why this paper is meant as an invitation to start a public law-oriented discourse about the legal concept of “constitutional identity”, with the aim of creating an analytical framework to complement its existing doctrinal and normative views, which eventually allows us a more compact understanding of formal and informal constitutional change. For this exercise, we should not disregard the fact that even though legally formulated and applied constitutional identity seems to be a Global North phenomenon, it offers us the opportunity to open up a comparative constitutional discussion with the Global South about its legal designs in international, supranational and constitutional texts.

The comparative analysis, which this paper completes from an admittedly positivist perspective, is meant to be only a rudimentary experiment which, with further investigations and discussion, might lead to a more coherent constitutional law theory on constitutional identity or its unfeasibility. Therefore, the logic followed is as follows. First, the regional application of “constitutional identity” is explored, and it is concluded that its legal equivalent is “the identity of the constitution”. It is seen as some part of the constitution, which legally may be used against any attempt to radically change the constitution and, consequently, the constitutional setting. Based on these findings, now by deduction, the identity of the constitution is explored in the Global South’s constitutions with the obvious goal of discovering congruencies or incongruences, and common challenges.

Constitutional identity has only just started to spawn more substantial literature2, and those works that can already be found on bookshelves3 address constitutional identity from neither a positive law nor a European integration perspective. A Global South perspective is not included in these works either, even though - from an academic viewpoint - we could consider Eastern Europe as a region belonging rather to the Global South (Bonilla Maldonado, 2013, p. 5 - 12). That is why this contribution uses the constitutional identity of Hungary, an Eastern European Member State of the EU, as a model to illustrate how and why constitutional identity could become detrimental, with some other EU Member States (Germany and Italy, together with the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)) exemplifying at the same time how the very same constitutional identity can be used to further unify and consolidate European integration. Based on these trains of thought, public discourse about the interrelationship and interdependency of constitutional identity (a non-legal term) and the identity of the constitution (a legal concept) may take place in which experiences of the Global South should feature. It is Daniel Bonilla Maldonado who is mindful of the differences between the Global North and the Global South, in terms of academic achievements and scholarly works (Bonilla Maldonado, 2013, pp. 5 - 12). This contribution currently cannot be about the “Common Ground in Constitutional Reasoning”4 about constitutional identity, but it could represent the “Towards” in the title of this issue5. Therefore, the goal of this article is to open a discussion and offer only some rudimentary conclusions whether any lessons learned from the Global North can be applied in the Global South and vice-versa.

2. Application of the “constitutional identity”: identity of the constitution

Based on the three states that have already developed and applied the legal term “constitutional identity” in the EU, three models (the German confrontational with EU law model (Lisbon decision (BVerfG, Judgment of the Second Senate of 30 June 2009,6 2 BvE 2/08), OMT reference decision, BVerfG, 14 January 2014, 2 BvR 2728/137), the Italian cooperation with embedded identity model (decision n 24/2017 of the ICC8), and the Hungarian confrontational individualistic detachment model (22/2016 (XII.5) Decision of the HCC, Dissenting Opinion to 23/2015 (VII.7) Decision of the HCC9), two attitudes (EU-friendly and antagonistic), three legal procedures (against EU and international human rights law and constitutional amendments) and one communication channel (preliminary ruling procedure) can be identified in which “constitutional identity” displays legal relevance. It also follows from the case law of the three jurisdictions that when applied in legal proceedings, “constitutional identity” is meant to refer to the “identity of the constitution” (BVerfG, 2009, Judgment of the Second Senate, paragraphs 208).

2.1. German approach - confrontational model

In Germany, the concept of constitutional identity was only used in 1928, in the theories of Carl Schmitt and Carl Bilfinger, to justify the limits of constitutional amendments to the Weimar Constitution (Polzin, 2016, pp. 411 - 438). Under the regime of the Grundgesetz (GG), following the latest reforms of the EU in Lisbon, it re-emerged in the jurisprudence of the Federal Constitutional Court (from now on BVerfG) in connection with the same subject matter (identity review), and it was associated with and used vis-à-vis European law (ultra vires review). Briefly, the link between the amendment power and EU law is as follows: if there are certain values entrenched by the constitution which cannot be changed even by the constitution-amending power, it is not possible to transfer competences to the EU, the using of which may result in the violation of those very same entrenched values. As a matter of fact, the BVerfG was concerned with domestic “unconstitutional constitutional amendment” issues in only a handful of cases. This is viewed as a result of the fact that “eternity clauses” have achieved the policy goals (there is now little chance of turning Germany into a dictatorship), and they have been underpinned by the written and unwritten rules of the political culture (the requirements for an increased majority for constitutional amendments, co-operation, and checks and balances within the coalition). Eternity clauses today are viewed as a legal lifebelt: they form the basis of German political culture and have broad popular and political support; their dismantlement would be intolerable and unsupportable for the majority of citizens (Küpper, 2014, pp. 85 - 89)

Reading eternity clauses as establishing constitutional identity was thus triggered by the reform of the European Union via the especially Article 4.2 of the TEU and appeared in the jurisprudence of the BVerfG10 (in and after the Lisbon decision, 2009). It follows that the identity of the GG covers immutable provisions (Art 79.3 GG) and the very essence of state and popular sovereignty. German courts hold a confrontational position vis-à-vis EU law, but after a power play and “dialogue” with the CJEU,11 dialogic interaction with the CJEU, the identity claim, based on Article 4.2 TEU and the identity review (BVerfG, 2009, Judgment of the Second Senate, paragraphs 1 - 421), seems to have bee subsumed within the European human rights protection ensured by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (Charter) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), as far as human dignity is concerned.12 The CJEU, in the Aranyosi and Căldăraru cases (Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 5 April 2016 upon the request for a preliminary ruling from the Hanseatisches Oberlandesgericht in Bremen, 2015), suggested that the German court might read the Charter of the EU and the ECHR jointly in deciding whether or not the state was complying with a European Arrest Warrant in cases that would potentially lead to the infringement of the human dignity of the person whose extradition was required, due to the prison situation of the requesting states. This exercise would make it unnecessary to activate the identity review (based on Article 4.2 TEU) because, even without jeopardizing the unity and supremacy of EU law, it might achieve the same goal (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment) as aimed at by the eternity clause of the GG (human dignity).

The communication tool for settling the issue at hand, unlike in Hungary but similar to Italy in Taricco, is the preliminary ruling procedure.

2.2. Italian approach - model of co-operation and “embedded identity”

Italian scholars ascertain that the Italian Constitutional Court (Italian CC), prior to its Taricco decision, in which it asked the ECJ to clarify whether its decision in Taricco I did actually leave national courts with the power to disapply domestic norms, even to the extent that this conflicted with a fundamental principle of the Constitution (the principle of legality in Article 25), never used the word “constitutional identity” as a way to define the relationship between domestic and EU law. Previously the Italian CC preferred the use of the doctrine of counter-limits, and now, in the most recent Taricco judgment (2017)13, it focused more on the concept of constitutional traditions of Member States. The notion of constitutional traditions is, however, pluralistic, in contrast with constitutional identity which is, by design, not. In the assessment of scholars, for Italy, the process of European integration represents the perfect fulfilment of the Constitution; therefore it is the common constitutional traditions, and not the individual constitutional identity, that form the source of legal inspiration (Fabbrini and Pollicino, 2016, p. 15). Italy, more clearly than Germany, seems to expand its “constitutional identity” to include EU membership. Being one of the founders of the EU, Italy could be viewed as the first state to enrich its national (Italian) identity with a European identity, identifying with the success of the European integration project - a project based on common interest and legal traditions. The Italian constitutional rules (with which the Italian CC has identified the Italian constitutional system to a certain extent) prevailed alongside the maintenance of a unified EU legal order. The CJEU, in Taricco II, was open to the Italian CC approach and arguments, which led to a judgment that respects “identity” embedded in constitutional legal traditions.

On the other hand, the counter-limits doctrine has had important implications as regards the unamendable core of the Italian Constitution. The Taricco case concerned only one of the many constitutional provisions that form the core principles of the constitutional order. These rules are “integration proof”, in the sense that, as held by the Italian CC, in the very unlikely case that these constitutional provisions were to be infringed, the Italian CC could review the acts of the EU institutions. The Italian CC, however, has never declared any EU law unconstitutional on the basis of the doctrine, and was not very keen to explain the term “fundamental principles of the constitutional order” (Claes and Reestman, 2015, p. 955). Scholarly works tend to see this formulation as covering the unamendable provisions of the Italian Constitution, which cover the republican form of state, including, for example, the principles of democracy and equality, rules on the election of the President of the Republic and the limited term of that office as stipulated in Article 139 (Constitution of the Italian Republic).

It thus seems that even if neither the CJEU nor the Italian CC has used the term “constitutional identity” to mark the distinctiveness of Italy, or even if nationalistic approaches have not been adopted in Italy (Fabbrini and Pollicino, 2016), the result of the Taricco saga has been that one of Italy’s constitutional provisions has prevailed: the understanding of criminal legality in Italy is preserved and respected by the authorities of the EU through an interpretation that also works for the CJEU. Reference to the common constitutional traditions of Member States is used to ease the paradox of the emergence of their identity in a community based on similar legal values and aspirations.

2.3. Hungarian approaches - confrontational individualistic detachment from supra- and international obligations

The Hungarian identity review appeared in the 22/2016 (XII.5) decision of the Hungarian Constitutional Court (HCC), along with the fundamental rights and ultra vires review,14 but has not been activated yet. The HCC declares that the constitutional identity of Hungary is rooted in its historical Constitution and has not been created but only recognized by the Fundamental Law (the partisan constitution of Hungary of 2012, ‘FL’). Even though the Court holds that the constitutional identity of Hungary cannot be featured by an exhaustive listing of values, it nevertheless mentions some of them, such as freedoms, the division of power, the republican form of state and freedom of religion. The decision was triggered legally by the request of the ombudsman, submitted one year earlier, following the refugee “quota decision” of the EU (Council Decision, 2015), which the Government opposes because it fears the alteration of the ethnic and religious composition of Hungary. It was also demanded politically due to the failure of a constitutional amendment just one week before the delivery of the ruling. The constitutional amendment, as a result of an invalid referendum on the “quota decision”15, was meant to incorporate the term “constitutional identity”, defence of which would have been the duty of all, with a view to constitutionally opposing the future implementation of the “quota decision” (Drinóczi, 2017).

The HCC, which is seen as a packed court as stated by the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, by declaring the identity of Hungary, informally amended the FL. It assisted the Fidesz Party to achieve its political agenda and created an ambiguous implicit eternity clause, previously unknown in the constitutional system of Hungary and refuted even by itself. The HCC, unlike the BVerfG, the Italian Constitutional Court or the Polish Constitutional Tribunal (Decision K 18/04, 2005), has mentioned neither the application of the preliminary ruling procedure in resolving the identity-related conflict with EU law, nor the legal consequences of such a clash. Nevertheless, it opened up the Hungarian constitutional system to the constitutional review of unconstitutional amendments, which - together with the “identity of Hungary” - may be a double-edged sword. Not contesting at all the importance of this kind of review, which is necessary if constitutionality is to be maintained, when the constitution itself is not in line with certain international and supranational standards, even though it is constitutionally bound by them, the non-standard-like provisions may be preserved by the constitutional courts. In Hungary, based on the new doctrine of constitutional identity rooted in the historical Constitution, the HCC enabled itself to defend the most criticized provisions of the FL16 against a constitutional amendment which has the aim of improving the constitutional content and raising it to the same level seen in the common constitutional tradition of Member States and international human rights obligations (Drinóczi, 2017). Furthermore, the language of constitutional identity in Hungary rather shows a tendency towards individualistic detachment from the common European project17, which was first characterized by abusive constitutionalism (Landau, 2013) but has quickly evolved into an illiberal constitutionalism (Drinóczi and Bien-Kacala, n.d.).

This attitude is also present in a Dissenting Opinion in which constitutional identity was invoked vis-à-vis a decision of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)18. A Justice of the HCC concluded that although Hungary is obliged to execute ECtHR decisions, it is not thereby forced to abandon its constitutional identity. The ECHR, however, does not contain a provision similar to Article 4.2 TEU, nor use the expression “constitutional identity”19. The ECtHR may agree that some constitutional characteristics do not constitute an infringement of the ECHR (Leyla Sahin v. Turkey, 2005) (Dogru v. France, 2008) or it may decide otherwise (Sedjic and Finci v. Bosnia Herzegovina, 2009) (Otegi v Spain, judgment, 2011). The standard in these cases is not the constitutional identity of the state; the ECtHR does not seek to explore this. With regard to the constitutionality of the different regulations for ex lege recognized churches and other religious communities, and their consistency with the ECHR, the single argument in the Dissenting Opinion is that constitutional identity manifests in “the historical fact of social involvement”, a point which is neither explored nor justified. Similarly, it is not explained why differentiation has nothing to do with the essential content of the freedom of conscience and religion, or with the terms of the ECtHR regarding the collective freedom of religion (Magyar Keresztény Mennonita Egyház and others v. Hungary, 2014). All of these explanations would have been especially necessary in the light of the ECtHR’s ruling, which emphasized that the recognition of churches relates to the historical, constitutional traditions of the state. In the case at hand, however, the ECtHR claims that the Government did not justify that the ex lege recognized churches fully reflected Hungarian historical traditions to the extent that the applicant church was not included. The ECtHR also perceived as problematic the fact that the legislator referred all the way back to 1895 yet failed to take into account more recent historical developments (Magyar Keresztény Mennonita Egyház and others v. Hungary, 2014). Parliament thus applied a selective historical view of the identity of Hungary. However, it is well known that the past is interpreted in a way which pleases the interpreters, and only those elements of the past are acknowledged which satisfy their self-interest (Gyáni, 2008).

2.4. European Union level

Article 4.2 TEU may be seen as triggering a “dual” designation: within the EU, Member States refer to their “constitutional identity”, while the CJEU prefers to use the term “national identity”. The two terms, however, refer to the same obligation of the EU institutions (“respect”) and the same “core” element of the constitutional setting of the particular Member State (“to be respected”).

The approaches of the CJEU and of the national courts to the actual content of “identity” differ though. The term “national identity” (Article 4.2 TEU) applies to determine whether the actions of the EU are legitimate20; the term “constitutional identity”, based on the jurisprudence of the high courts or constitutional courts, has the aim of defending the constitution and constitutionality. Previously, the debate about the clarification of the content of identity (Article 4.2 TEU) focused on who would have the last word and how the dialogue between the CJEU and national courts would ease the tension between the different roles and approaches of these courts. The practice has already provided answers: an active and co-operative use of the preliminary ruling procedure and the application of integration-friendly arguments, which may result in a better understanding of national constitutional concerns.

3. The identity of the constitution

In the words of Jacobsohn, Rosenfeld, Tushnet and Śledzińska-Simon, there is no identity without knowing myself (sameness and selfhood) and the something else against which I identify myself as me; there is no identity without the individual, relational and collective self (Jacobsohn, 2010, pp. 133 - 135) (Rosenfeld, 2011) (Tushnet, 2010, pp. 672 - 675) (Śledzińska-Simon, 2015, pp. 137 - 139). From the European case law it seems that the term “constitutional identity” is used in many ways (confrontationally and co-operatively) to preserve the uniqueness of the constitution and, consequently, the sameness of the state and its people. The “collective identity of the constitutional subject” (or national identity), which the constitutional subject as a constituent deemed to be important to incorporate in its constitution, is expressed in various provisions in different constitutions.

3.1. Identification and textual analysis

Provisions expressing the “collective identity of the constitutional subject” may cover many parts of the constitutional text, starting with the name of the constitution, the name of the state and its symbols, national or official languages, and statehood. The subject of the constitution-making and amending power, which in the majority of cases is located in the constitutional text, may tend to correlate with the historical sentences of the preamble. But in fact, in the EU, out of the 27 Member-State written constitutions, 11 do not have a preamble, the constitutions of mostly Western European states have only a symbolic preamble (France, Italy, Germany), while others (mainly post-socialist countries, and Portugal and Spain) have a rich and comprehensive preamble to define their own national identities in the face of their previous oppression (Fekete, 2011, pp. 35 - 38).

As for the designation of the constituent people or the body that actually adopted the particular constitution, Member States display a great variety, but there are distinct models. Constitutions have been adopted by a constituent assembly (Bulgaria, Germany, Italy and Portugal), the parliament (Hungary and Slovenia), citizens together with the freely elected representatives (Czech Republic, Slovakia), and by the people or the nation. There are also many versions of how the people or the nation came to adopt a constitution: the people may have adopted it acting alone (France and Ireland) or together with minorities living in the state (Croatia), or following a referendum (Estonia, Spain); or the nation, which consists of the citizens, may have adopted it (Poland, Lithuania). Countries that have historically experienced extensive border changes (Hungary, Croatia and Slovakia) grant their minorities’ special constitutional status by elevating them among the constituent people of the state and constitution.

In the vast majority of cases, the reference to the people or nation who adopted the constitution is associated with the amendment process as well, which may require the involvement of the people (e.g. in Austria, for the total revision of the constitution it is obligatory, but this is excluded in Germany and Hungary). In some cases (i.e., Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Moldova, and Serbia), a tiered procedure is used, which creates “different rules of constitutional amendment for different parts of the constitution” (Dixon and Landau, 2017)21, in which certain provisions, usually eternity clauses, may be altered only by referendum. Other parts of the constitution are to be modified by parliament. In Poland and in Austria, less demanding but still slightly stringent procedural rules apply. The referendum is optional: it is called when the amendment concerns the republic, fundamental rights and the rules on constitutional amendment, if it is requested by those entitled to submit a constitutional amendment (MPs, the Government and the head of state) as stipulated in Article 235 (Constitution of the Republic of Poland); or, in Austria, when the amendment does not aim at total revision, as stipulated in Article 44 (Austrian Federal Constitution). In the case of Poland, it is questionable whether even a more demanding tiered constitutional amendment could preserve democracy and the identity of the Constitution (Dixon and Landau, 2017). The Polish Government, since 2015, has systematically dismantled the constitutional system established by the 1997 Constitution (Bien-Kacala, 2016). The technique used has been to change the meaning of the Constitution by informally amending it: due to lack of political support, the Constitution could not be properly and formally amended. The change, which amounts to the overturning of the Constitution, is accomplished informally by the adoption of purely and obviously unconstitutional laws, and by the pursuit of unconstitutional practices. In Croatia and Italy, the tiered mechanism, unlike in other states, is not designed around a particular part of the constitution but entrenches a special referendum procedure: the parliament must call a referendum in connection with the proposed constitutional amendment, when so requested by 10 per cent of the voters in Croatia as stipulated in Article 87 (Constitution of the Republic of Croatia), or by 500,000 voters in Italy as stipulated in Article 138 (Constitution of the Italian Republic).

Most Member States have called referendums on accession to the EU and treaty reforms, and with regard to the latter, they usually require an increased (super-) majority voting. In 2003, the states that would join the EU in 2004, except Cyprus, held referendums. In Hungary, even the accession referendum question was incorporated into the Constitution, and each constitution was made “open to the EU” by adopting EU clauses, extending the right to vote to elections to the European Parliament, and adjusting the relationship between national governments and parliaments in integration matters. It seems to be safe to say that constitutions are including these provisions because the people wanted them there, as they have decided to belong to a European community in its legalized, actual version22.

The “collective identity of the constitutional subject” may also be discovered in the principles uniquely featuring the state and the constitutional order, among which eternity clauses may be emerging. Several constitutions contain eternity clauses, such as the GG in Germany, the Italian, Czech and Polish Constitutions, but not the Hungarian FL. Principles uniquely featuring the state and the constitutional order cover the form of state (monarchy or republic), the form of government, and the commitment towards the rule of law and human rights protection. Democracy is also named and associated with popular sovereignty, which can be exercised directly or indirectly depending on the actual choice of the constituent23. The territorial structure (unitary, regional, federal or devolved) is also a distinct feature, which usually has an historical background, without which the state will not be the same. That is why, usually, Articles on territorial structure are entrenched as eternity clauses (e.g., in Germany, Austria, Spain). These provisions are partly components of state sovereignty and popular sovereignty (in so far as the consent of the people is required for changing them).

3.2. The “identity of a constitution” and some of its models

It may be concluded that the “identity of the constitution” is to be found among the provisions of constitutional texts and related jurisprudence that specifically and exclusively feature a status that was drafted during the constitution-making process and shaped by either formal or informal constitutional amendments. The identity of a constitution may differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and the applicability of constitutional provisions may be subject to the jurisdiction of the respective constitutional or high courts. The constitution, by including these provisions, may have its individual and collective and relational selves, which are, as a second tier, sustained by procedural rules on constitutional amendment processes that create the link with the people (“collective identity of the constitutional subject”). Democratic constitutions need to reproduce the will of the constituent people and also be able to adjust to the change of the collective identity of the constitutional subject by this subject, the people. Both the state and the people, when considering these constitutional provisions, can experience the individual, the relational and the collective, and the “procedural” sameness and selfhood.

The legally applicable “identity of the constitution” comprises those Articles that can be employed vis-à-vis EU law and unconstitutional amendments, and which are intended to be applied in the face of international human rights obligations. Case law throughout the EU indicates that the identity of the constitution, which the EU shall respect, embodies constitutional provisions through which the state can identify itself in a community (as a state with all its attributes), and others that show uniqueness but which can be subsumed with a common European human rights regime and the constitutional traditions of Member States. For that, a joint effort, co-operation and acceptance are needed from both the CJEU and national courts, which seem to be realized where there is a palpable commitment to the European project. Formal and informal unconstitutional constitutional amendments that infringe the eternity clauses or the core content of the constitution, and which lead to an irresolvable conflict with supranational and international obligations, generally seem to occur in Hungary and Poland, and have thus far been almost undetectable elsewhere. Unlike in several Member States, the Hungarian FL does not entrench anything and does not allow the people to decide on constitutional matters. Also uniquely, only the HCC, in its constitutional interpretation, has deduced the definition of the constitutional identity of Hungary without any textual basis. It identified certain principles as comprising the identity of Hungary, and did not refer to EU-related procedures or the importance of the involvement of the people in amending processes that may affect that identity. If the “collective identity of the constitutional subject” is truly articulated in the constitution and shaped by amendments and interpretations, and is legally demarcated by certain constitutional rules, as discussed above, it seems that both the constitutional identity of the people of Hungary, who still support the Fidesz Party, and the identity of the FL do indeed display confrontational individualistic detachment. This detachment apparently has the potential to disregard the common constitutional traditions embedded in regional human rights protection and the European project.24 The HCC has helped to “stock up” the FL with “unconstitutional rules” by not declaring them unconstitutional, and now is ready to carve in stone the exact same provisions by bringing them together under the heading “constitutional identity of Hungary”, a notion which the Court itself invented and, by an informal constitutional amendment (ultra vires interpretation), incorporated into the constitutional text. Now, if the Court takes itself seriously in the future, it has to revisit its dismissive position on the possibility of the substantive review of constitutional amendments, even in breach of the express constitutional rule allowing only procedural review.

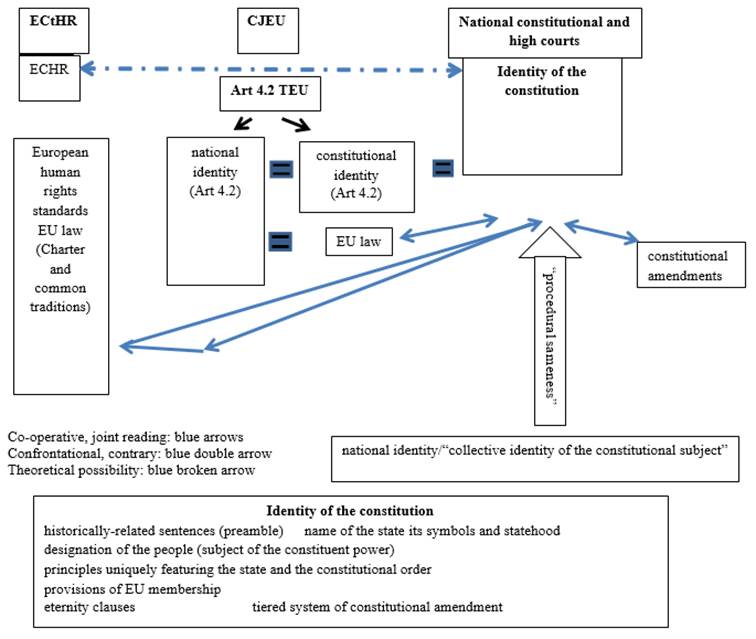

Figure 1 shows the interconnectedness and graphic imagery of the conceptualization of the identity of the constitution, as explained above.

4. Identity of the constitution and constitutional identity in Latin America - open for debate

As Latin American states are constitutional democracies, it is assumed that, based on the above findings, the identity of the constitution may be explored in the Global South’s constitutions even if regional economic integration in the Global South is less unified and the history of constitutionalism is different in the two regions. In Latin America, two types of constitutional change may suggest that the identity of the constitution is to be altered: the adoption of a new constitution and the amendment of the limitation of the term of office of the president.

4.1. Textual analysis

Designers of some constitutions (Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador) seem to choose the tiered system of constitutional amendment, including for the adoption of a new constitution. For these changes, the involvement of the people, which, according to the current constitutional texts, includes indigenous peoples, is a prerequisite and is entrenched (Bolivia and Ecuador). If a new constitution is to be adopted, a constitutional assembly is convened by the people, and the adopted text also has to be submitted to a constitutional referendum. In Bolivia, as stipulated in Article 411, the same process applies when the constitutional reform affects the “fundamental premises, the rights and duties and guarantees, and the supremacy and reform of the constitution” (Political Constitution of the Plurinational State of Bolivia). This is not a uniform practice; for example, the Brazilian, Chilean and Peruvian Constitutions do not specify how a new constitution should be adopted, and the Nicaraguan Constitution does not apply a tiered mechanism.

The entrenched parts of a constitution are referred to by the following formulations: “fundamental premises, the rights and duties and guarantees, the supremacy and reform of the constitution” as stipulated in the Political Constitution of the Plurinational State of Bolivia; “fundamental structure of the Constitution”, “structure and fundamental principles of the constitutional text” as stipulated in Articles 340 and 342 (Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela); “fundamental structure, the nature and constituent elements of the State”, constraining the rights and guarantees and changes of procedure for amending the constitution as in Article 441 (Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador). From a textual point of view, these rules may be interpreted as referring to hundreds of Articles, which suggests that the “identity” captured in these provisions is meant to be preserved and is liable to amendment only in those cases to which the people consent. The uniqueness (sameness and selfhood) of Latin American constitutions, in which the identity of the constitution embodying the collective identity of the people may be captured, is to be found in those provisions which show either that the constituent has adapted and contextualized the ideas of the European constitutional democracies (neoconstitutionalism) (Piovesan, 2017), or has created more distinct, even contrasting, elements from the constitutionalism of the Global North (Gargarella, n.d.). A common element is that constitutions have targeted the region’s main challenges: inequality that has a racial and ethnic dimension, poverty, exclusion, lack of human rights compliance, weak institutions and problems of political representation (Piovesan, 2017). All of these challenges found their place among the entrenched provisions of the Constitutions of Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador. Along with the tiered constitutional design requiring the involvement of the people, entrenchment expands to cover declarations on plurilingualism, multinationalism, multi- or interculturalism, and the acknowledgement of multiethnicity and plurinationality, which are in close correlation with the recognition of collective subjects (indigenous peoples) as political actors. Features that differ not only from those of the constitutions of the Global North but also from those of neoconstitutionalism are also found among these provisions. These constitutions are based on axiological premises rather than legal assumptions. The legal self-determination of the state is expressed as, for example, the “constitutional state of rights and justice” (Ecuador), the social State of Law and Justice (Venezuela) and the social state of communitarian law (Bolivia). In Bolivia, the determination of ethical, moral principles of the plural society, which the state adopts and promotes, such as “live well and harmoniously”, “good life”, “noble path or life”, precedes values with a clearer legal content on which the state is based, such as unity, equality, inclusion, dignity, liberty, solidarity, reciprocity, respect, interdependence as stipulated in Article 8 (Political Constitution of the Plurinational State of Bolivia). In Ecuador the reference to “rights of the good way of living” (buen vivir or sumak kawsay) appears in the preamble as well as throughout the constitutional text, and such rights are both connected to the general interest and prevail over individual interests. This constitutional setting, which was adopted by a constitutional assembly and supported in a popular referendum, cannot accommodate values advocated by the Global North’s constitutionalism. It thus can potentially frustrate the fundamental rights and traditional principles of a constitutional democracy (the rule of law, legality, the division of power, etc.); it represents another “constitutional identity”, as is apparent from the decisions of the Constitutional Court of Ecuador (Salazar, n.d.), from now on ECC. As has been said, these provisions are entrenched by a tiered constitutional technique, which accomplishes more popular involvement of citizens, including indigenous and vulnerable peoples, and makes constitutions rigid (Dixon and Landau, 2017) , and thus more resistant to inconsistent changes, but also more vulnerable to autocratic populism, which may abuse the very sense of popular involvement. An example is the constitution-making process in Ecuador, which involves abusive constitutional change by replacement (Landau, 2013). Therefore, the question is whether the identity of the constitution is a true map of the “collective identity of the constituent people”; after all, the notion of sumak kawsay was presented in the constitution drafting process by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (Salazar, n.d.) , or rather corrupted by the populist leadership and loyal and subservient courts.

The legal formulations of open statehood, the conventionality control (control de convencionalidad) and the block of constitutionality (bloque de constitucionalidad) (Góngora-Mera, n.d.) also seem to be entrenched in Bolivia and Ecuador. Their aim is completely different from that of the integration clauses in European constitutions. Constitutions are keen to prove their human rights commitment because states are concerned about their international standing, which may also be a response to historically weak protection of fundamental rights (Bogdand, n.d.). This approach might be expected to lead to a more unified human rights protection, which could also contribute to the realization of democracy and the rule of law, or even curb the unperishing yearning of the region towards hyperpresidentialism25. In certain cases of political importance, such as the conflict surrounding the right to vote and the limits on the term of office of an elected official, it is not, however, the case.

4.2. The practice

A limited presidential term is usually not entrenched in the region, which allows presidents to undermine democracy and the separation of power by seeking to eliminate or extend their terms of office. In Colombia, this did not succeed. The Constitutional Court struck down a proposed referendum on a constitutional amendment that would have allowed the President to seek a third consecutive term of office. It utilized the doctrine of unconstitutional constitutional amendment (Dixon and Landau, 2017), which it had previously constructed by informally amending the Constitution. However, Colombia does not adopt the New Latin American constitutionalism, as opposed to the other three countries discussed below.

In Venezuela, the abolition of the limitation on the re-election of public officials was not regarded as changing the fundamental structure and fundamental principles of the constitutional text, as the National Assembly adopted and a referendum supported the first amendment of the Constitution in 2009. In Bolivia too, a limitation on re-election does not seem to involve the “identity of the constitution”, through the principle of democracy, which cannot be changed by an ordinary amendment process. However, in both Bolivia and Ecuador, it was not the people who decided on the amendment of the text with a view to removing the limitation but the constitutional courts, mainly following the same arguments. In 2016, Bolivian people, through a referendum, rejected the constitutional amendment on the removal of the limitation on the re-election of the President adopted through an ordinary constitutional amendment procedure. Supporters of the incumbent Morales regime asked the Constitutional Court to declare unconstitutional a constitutional provision that limited re-election, which the Court did in November 2017. The Court ignored the referendum result of 2016, and, by using a strong conventionality doctrine and the pro homine principle of the block of constitutionality (Góngora-Mera, n.d, p. 251), gave priority to the political right of the people to choose their own representative and the original but finally unadopted will of the constituent over the constitutional limits on re-election (Verdugo, 2017). Very similar arguments are used in Ecuador, where the parliament in 2014 amended the Constitution to remove limits on the terms of office of all public officials, including the President. As the Constitution requires the ECC to determine which amendment process is to be followed, it was up to the Court to decide whether the removal of the limitation on re-election amounted to alteration of the “fundamental structure” of the Constitution. The ECC allowed the parliament to pass the amendment without a referendum. It argued that the amendment expanded the “people’s constitutional right to elect and be elected and did not alter the ‘fundamental structure’ of the Constitution”, as “the framers did not consider political alternation part of the fundamental structure of the Constitution or one of the constituent elements of the State” (Guim and Verdugo, 2017). Now, President Lenin Moreno has proposed a referendum to repeal the constitutional provisions that would allow Rafael Correa to run for a third time and return as President (Guim and Verduga, n.d.), and the ECC should have decided which amendment process was to be followed. However, it did not happen as the ECC remained in silence “exceeded its 20-day window to issue a ruling, after which Moreno convened the vote via two executive decrees in late November 2017” (John Polga-Hecimovich, 2018). The constitutional changes, including limiting all elected officials, such as the president and parliamentarians, to a single re-election, took effect immediately (John Polga-Hecimovich, 2018) If the Court had delivered a ruling, it should have decided whether the voting rights of the people were considered to belong in the entrenched part of the Constitution or not. If they had belonged in that part, the more stringent process should have been activated. Here, a similar issue could have emerged as in Hungary: the ECC, by relying on an entrenched rule which was assumed to show identity, could prevent the improvement of the Constitution. It seems, however, that in this particular case, no actors have observed constitutional amendment rules; yet democratic improvement was achieved. Nevertheless it is not guaranteed that these reforms will be long lasting (John Polga-Hecimovich, 2018) which may give a chance to the ECC to deliberate on the issue of the “identity” of the Ecuadorian constitution”.

5. Conclusion

The legally conceptualized and applied “identity of a constitution”, which is a Global North - more specifically EU - phenomenon, have similar relevance in contemporary constitutional democracies as far as constitutional changes are concerned. Based on the regional European jurisprudence and doctrinal works, it is concluded that the “constitutional identity” in a legal context is the “identity of the constitution”. In this context, the identity of the constitution is found among provisions of constitutional texts and related jurisprudence that specifically and exclusively feature a status that was constituted during the constitution-making process and shaped by either formal or informal constitutional amendments. The “identity of a constitution” may differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and the applicability of constitutional provisions may be subject to the jurisdiction of the respective constitutional or high courts. The legally applicable “identity of the constitution” comprises those articles that can be employed vis-à-vis EU law and unconstitutional amendments, and which are arguably intended to be applied in the face of international human rights obligations. Case law throughout the EU indicates that the identity of the constitution, which the EU shall respect, embodies constitutional provisions through which the state can identify itself in a community (as a state with all its attributes), and others that show uniqueness but which can be subsumed within a common European human rights regime and the constitutional traditions of Member States.

As has been explored, Germany and Hungary exemplify the confrontational with EU law model. It is suggested that the model that emerged in the jurisprudence of the Italian CC should be called the cooperative model with embedded identity. It seems to be appropriate to call the Hungarian model a model of confrontational individualistic detachment, even if the identity review has never been activated. When the concept of the “identity of a constitution” is, mutatis mutandis, applied with view to discover the identities of the examined Latin American constitutions, we find that they seem to display the following features26: entrenched popular involvement in decision-making processes, which is in practice manipulated in Ecuador and disregarded in Bolivia; recognition of indigenous peoples as political actors, with vindication of their rights and institutional guarantees thereof, which in practice is neither observed nor facilitated by the courts in Ecuador (Salazar, n.d.); the vision of a plurinational, multi-ethnic, multilingual and diversity oriented state (Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador); axiological principles, allowing hyperpresidentialism by formal and informal constitutional amendments; and entrenched “open statehood”.

Nevertheless, when legally applied, the “identity of a constitution can be a double-edged sword even in the Global South, where this notion has yet to receive exposure. As evidence shows, it could adequately reflect the actual identity of the constituent people, rooted in the past and overarching the future. It also can contribute to the realization of a legal project, such as the EU, or regional human rights protection, and to the greatly strengthened protection and involvement of indigenous and vulnerable peoples in the Global South. However, in the hands of autocratic and populist leaders and subservient constitutional courts, it can be abused and lead to the dismantling of regional and national legal achievements by relying on the very same ““identity””, which could quickly be turned into autarchy. If it is not abused, the challenge seems to be the reconciliation of new and traditional ideas of constitutionalism, the engine of which must be an independent judiciary.