An approach to mediation

Alternative dispute resolution methods are those that resolve controversies without the need to go to court. Typical methods include: neutral assessment, negotiation, conciliation, mediation and arbitration (Legal Information Institute, 2007). These are based on mutual understanding and cooperation principles, in order to settle a conflict in a peaceful way (Gonzalo, 2011, p. 32).

The term “mediation” can have different meanings depending on the context in which it is used or depending on whether its emphasis relies on the procedure or on the outcome (McGuinness, 2010, p.19). However, in an effort to shape what mediation concentrates, it has been defined as “[...] a non-adversarial procedure, where a neutral third party-the mediator-conducts a negotiation process, assisting the parties to arrive to an agreement”2 (Gozaíni, 2001, p.99). Mediation is seen as an informal alternative process to litigation, where professionals in negotiation help the parties jointly reach an agreement (Legal Information Institute, 2007).

Mediation has as its essential characteristic the willingness and consent of the parties to participate in it. In addition, mediators act as neutral third parties who construct a framework of cooperation between the parties, so that they can reach their own agreement (Gozaíni, 2001, p. 99). “Mediation seeks to incorporate the so-called co-existential justice, where the acting body ‘accompanies’ the parties on their conflict, guiding them with their advice in the rational search for answers that overcome the crisis” (Gozaíni, 2009). Likewise, mediation is conceived as a confidential space, giving the parties the opportunity to speak freely and make proposals for resolution in confidence that this will not affect any subsequent judicial process.

What mediation finally seeks is that the parties reach an agreement (2009, p.100), whether it is appropriate to the normative solution, or not necessarily, as it is explained later on this article.

[M]ediation starts from a different principle. It is not a matter of reconciling opposite interests that look at the same situation (contractual or de facto); but to find a peaceful response, a flexible alternative that does not have the precise framework of the analyzed perspective, being able to obtain absolutely different results from the typical picture that qualifies the pretension and its resistance (Gozaíni, 1995, p.15).

2. Recognition of mediation in the Ecuadorian regulatory framework

Mediation has been recognized in the Ecuadorian legal framework since the enactment of the Law of Arbitration and Mediation. This specialized law abolished the Commercial Arbitration Act (which was promulgated on October 28, 1963). Thus, it went from a law that only regulated arbitration to one that regulates both mechanisms (Poveda, 2006, p. 10).

The 1998 Constitution followed the trend of recognition of mediation in the country. Therefore, in its article 91, it was prescribed that “[i]t will recognize arbitration, mediation and other alternative procedures for the resolution of conflicts, subject to the law”. Likewise, the current Constitution (2008) reaffirmed this recognition by expressing in its article 190 that “[i]t acknowledges arbitration, mediation and other alternative procedures for the resolution of conflicts”.

On the other hand, the Organic Code of the Judicial Function, promulgated in 2009, establishes in its article 17 that:

[...] [a]rbitration, mediation and other alternative conflict resolution methods established by law, constitute a form of this public service [of administration of justice], as well as the justice functions exercised by indigenous peoples in their authorities.

Thus, since the promulgation of the Law of Arbitration and Mediation, mediation has had a greater normative recognition, even of constitutional rank.

Given this, the Strategic Plan of the Judicial Function has established as one of its objectives to promote optimal access to justice. Consequently, it has determined that within the strategies to reach this goal is indispensable to

2.6 Establish mediation centers and national courts of justice at the national level by fostering a culture of peace and dialogue to resolve conflicts; 2.7 Strengthen the mechanism of referral within the courts to alternative instances of conflict resolution; […] 2.8 Promote the use of judicial conciliation (Consejo de la Judicatura, 2013, p. 41).

In this way, the priority given to mediation in Ecuador as an adequate method for the settlement of disputes, and especially as a way to achieve optimal access to justice, is verified. Establishing the need to strengthen mediation it is also a call to the community to use this mechanism; and to practitioners, both mediators and lawyers, to extend the traditional concept of mediation and to continuously develop it through practice.

3. The orientation of mediation

Now, what does the mediator exactly do? How does the mediator facilitate communication and guide negotiation so that the parties reach an agreement?

The answer to these questions depend mainly on the vision that the mediator, the parties and the lawyers who accompany them, have on how mediation should be. This vision is called orientation and is composed of two important concepts. The first concept is the style of the mediator and the second is the definition of the problem.

Leonard Riskin (1994) has defined the facilitative and evaluative styles as opposites as to what the mediator does. He also considers that the definition of the problem can be distributive or narrow as opposed to integrative or broad, depending on the depth of the dispute (p.111).

In order to explain this in greater depth, this section will analyze the styles of the mediator [3.1] and the different approaches that exist regarding the definition of the problem [3.2]. On the basis of this the four possible orientations in the mediation will be exposed [3.3] and finally we will study the viability of the mediators to change orientations throughout the procedure [3.4].

3.1. Styles of the mediator

The styles of mediation have to do with the approach that the mediator has to the handling of the procedure. These approximations can either be facilitative [3.1.1] or evaluative [3.1.2], depending on the scope of the powers that the mediator attributes to itself within the procedure.

The facilitative mediator focuses on moderating the parties’ participation in the audience, exploring their true interests with them, and guiding them through questions so that they, themselves, find the appropriate solution to their dispute. From the facilitative understanding, the mediator is a referee in the game in which only the parties participate, and intervenes as little as possible so that it does not affect the outcome of the procedure.

On the contrary, the evaluative mediator seeks to intervene actively in the resolution of the controversy. In order to do so, it dares to make predictions about what would happen if no agreement is reached, to assess the weaknesses of the parties’ positions, to suggest formulas of agreement, and even to urge the parties to accept them. From the evaluative vision, the mediator is almost another player that changes the dynamics of the game, and actively participates without losing its neutrality.

3.1.1 Facilitative Style

It is said that facilitaive style is the essence of mediation, because in the beginning of mediation, the only style that was taught and practiced was what we now call facilitative (Zumeta, 2016). Mediation is a process of dialogue, that it is designed in such a way that the same parties identify and shape the solution they see most appropriate (Brown, 2002).

According to Carole J. Brown (2002), this style is based on three fundamental principles: (i) the self-determination of the parties for the resolution of the dispute; (ii) the neutrality of the third facilitator; and (iii) the third party is the one that facilitates communication between the other two parties, so that they can mutually understand their interests and find a creative solution.

Risking describes facilitative mediation as one in which the mediator assumes that the parties are intelligent, that they can work together with their counterpart and that they are able to understand and embrace their situation better than the mediator, and even, better than their lawyers. The solutions that the parties can give are more adequate than the solution that any other could give. Given the above, a facilitative mediator has as its main mission to clarify the points of discussion and improve communication between the parties (Brown, 2002), so that they decide what solution fits to their problem.

Consequently, the role of the facilitative mediator is severely limited. The mediator takes care of the procedure as such, but are the parties who must come to a solution (Nauss Exon, 2008, p. 579). The mediator structures the procedure and refrains from making recommendations or opinions regarding the controversy (Zumeta, 2016). The parties create and reach agreements and solutions for themselves, with the presence of a third party that is finally just this: one more in the room.

The mediator facilitates things so that those who attend the audience can speak frankly of their interests, leaving aside their adverse positions. Through appropriate questions and proper techniques, the parties can be taken to points of agreement and, if they do not reach agreement, the mediator cannot make any decisions about it because he cannot force them to do or accept anything3 (Gozaíni, 2001, p. 100).

The role of a facilitative mediator, according to Osvaldo Gozaíni (2001), involves 5 matters: (i) facilitate communication for the parties to listen to each other; (ii) organize the claims of the parties on the basis of needs and interests; (iii) consolidate the points or needs that the parties have in common; (iv) work on the points of controversy; and, (v) ensure that both parties are aware of their rights. To do this, the mediator delimits his participation in the conversation to ask questions, validate and normalize the opinions of each of the parties, explore the true interests of the parties and assist them so that they are the ones who arrive at a solution through brainstorming (Nauss Exon, 1997, p. 939).

It has been said that the facilitative style evokes what mediation really is, because it allows the parties to reach an agreement by their own, satisfying their interests, empowering themselves, and providing them with some therapeutic method (Roberts, 2007, p. 193). However, among criticisms of this style, it is considered that the mediator is too passive, which may hinder the reach of the agreement. Likewise, their passivity can create an imbalance between the parties, harming the weak. It is even said that if the mediator tries to balance the power situation between the parties, he would be violating the impartiality of the procedure (Nauss Exon, 1997, p. 602).

3.1.2. Evaluative style

Within the spectrum of mediator styles, on the opposite side to the facilitative style is the evaluative one. In this style, the mediator is more involved, assessing legal issues, party rights and/or interests and positions (Moore, 1998, p. 56).

The term “evaluation” refers to the process by which a neutral third party expresses his opinion about the possible outcome of a legal dispute in the event that it is to be settled in court (Golan and Corman 2010, p. 328). The objective of the mediator in this case is to offer the parties the vision of a neutral third party that allows them to see beyond their own postures. While their intervention tends to focus on legal or procedural issues, evaluative mediators may also take a similar stance-offering advice, predictions, or suggesting solutions-on substantive or even relational issues.

According to Dwight Golann and Marjorie Corman Aaron, an evaluative mediator can manage to change the perceptions and assessments that the parties have about their positions and alternatives. When a conflict is solved by ordinary methods of justice, both parties predict that they have high chances of winning. Within a mediation, if these high levels are maintained, it is difficult for the parties to develop negotiations in good faith and to reach mutually beneficial agreements (2010, p. 329).

Evaluation can cut through litigants’ misjudgments about the merits of a case. When disputants hear that a neutral person, after studying the facts and listening to the arguments, disagrees with their predictions of victory, they are motivated to look again at the case and ask what the evaluator has seen that they have not (Golann and Corman, 2010, p. 330).

Some scholars have referred to evaluative mediators as “directive mediators” or “muscle mediators”. The fact that the mediator offers a personal assessment of the conflict and its possible outcomes implies that it employs a degree of influence on the parties (Nauss Exon, 2007, p. 593). In any case, the activity of the evaluative mediator should never impose its own position.

Thus, instead of merely facilitating communication between the parties without having any influence on them; an evaluative mediator questions the points under discussion, provides procedural and substantive advice, predicts results, and suggests ways to resolve the conflict (2007, p. 592). Christopher Moore (1998) explains that

Evaluative mediators also commonly conduct reality testing with parties to uncover gaps in understanding, clarify weaknesses in arguments, identify where the law or past legal cases do not support a party’s views, overcome irrational assessments, encourage more realistic appraisals of parties’ cases, remind them of their underlying and long-term interests, and determine the potential benefits and costs of settling or not (p. 56).

As a result, the attitudes commonly assumed by evaluative mediators are: (i) to issue a legal criteria to help understand the strengths and weaknesses of the parties; (ii) give them an opinion about the possible outcome of the conflict if it were brought to the courts; (iii) give suggestions to the parties about the best alternatives to solve the problem; (iv) propose options for a settlement that satisfies the interests of the parties; and, (v) suggest a particular proposal for a solution to the parties. Evaluative mediators mainly use private meetings where they can speak freely with the parties about the weaknesses of their case. In addition, an evaluative mediator must have some degree of experience in the subject matter of the dispute in order to comply with the aforementioned activities.

However, evaluative mediation has also received some criticism. Among the main ones is that the mediator can compromise its neutrality and impartiality, as well as diminish the parties’ self-determination and autonomy, prevent their long-term empowerment, and increase levels of confrontation between them. For some, having “muscle mediators” necessarily implies a degree of coercion by a third party, which departs from the very essence of mediation: persuasion and not coercion (Skjelsbaek quoted by Smith, 1994). Similarly, professors Kimberlee Kovach and Lela Love (1996) refer to evaluative mediation as an oxymoron4, arguing that the essence of mediation and the evaluation done by mediators are inconsistent, given that impartiality and neutrality are fundamental principles.

Evaluative mediation is an oxymoron. It jeopardizes neutrality because a mediator’s assessment invariably favors one side over the other. Additionally, evaluative activities discourage understanding between and problem-solving by the parties. Instead, mediator evaluation tends to perpetuate or create an adversarial climate (p. 31).

3.2. Approach on the definition of problem

In addition to the style that a mediator can have, there is another factor that can guide the mediation. This is the vision of the problem to be addressed, which may be narrow or broad.

The definition of the problem is given in terms of the content that the conflict is understood to have. Thus, the conflict can be about several issues, such as (i) litigious aspects; (ii) commercial; (iii) personal; and, (iv) community (Roberts, 2007, p. 193). “The narrowest approach focused primarily on legal issues, but as the spectrum became broader, business, personal, relational, and community interests were also included” (2007, p. 189).

On the first level, mediation focuses almost exclusively on the claims of the parties from a legal perspective. The mediators who have this type of perspective focus the mediation in such a way that the parties see their alternatives in case of going to a judicial process. Thus, a mediator with a narrow vision of the problem will look at the possible outcome of the conflict if it were brought to court to avoid the risks of an unfavorable outcome, and will not give more importance to the issues surrounding the controversy, such as interests, emotions or causes of conflict. In this sense, Leonard Riskin (1996) argues that in a narrow approach

[…] the primary goal is to settle the matter in dispute though an agreement that approximates the result that would be produced by the likely alternative process, such as a trial, without the delay or expense of using that alternative process. The most important issue tends to be the likely outcome of litigation (p. 19).

The second level focuses on business or commercial issues. Accordingly, the discussion focuses on aspects that would not be taken into account in a judicial process. Leonard Riskin (1996) graphs this through the following example

[…] Golden State is displeased with the overall fee structure or with the quality or quantity of Computec’s performance under the contract, and the mediation might address these concerns. Recognizing their mutual interest in maintaining a good working relationship, in part because they are mutually dependent, the companies might make other adjustments to the contract. Broadening the focus, a bit, the mediation might consider more fundamental business interests, such as both firms’ need to continue doing business, make profits, and develop and maintain a good reputation. Such a mediation might produce an agreement that, in addition to - disposing of the $30,000 question, develops a plan to collaborate on a new business venture. Thus, by exploring their mutual business interests, both companies have the opportunity to improve their situations in ways they might not have considered but for the negotiations prompted by the dispute (p.19).

The third level, seeks towards a broader vision of the problem, revolves around the personal aspects of each of the parties. The objective is not only to solve the conflict, but this approach also gives the parties the opportunity to learn and change through the resolution of the conflict. So,

[...] the parties might repair their relationship by learning to forgive one another or by recognizing their connectedness. They might learn to understand themselves better, to give up their anger or desire for revenge, to work for inner peace, or to otherwise improve themselves. They also might learn to live in accord with the teachings or values of a community to which they belong (Riskin, 1996, pp. 20-21).

Thus, using the same example used to demonstrate the approach to commercial issues, Leonard Riskin (1996) argues that

Level III mediations focus attention on more personal issues and interests. For example, during the development of the $30,000 dispute, each firm’s executives might have developed animosities toward or felt insulted by executives from the other firm. This animosity might have produced great anxiety or a loss of self-esteem (p. 20).

Indeed, in a mediation focused on personal issues, a process of change will be sought in the parties so that through mediation they can ventilate their emotions and forgive each other.

Finally, the fourth level consists of a very broad vision of the problem that surrounds itself in community and social aspects. Hence, during the mediation the desires of social groups that are not part of the dispute in the strict sense, but that in one way or another may be affected, are still considered. Following the same example used in previous lines, Riskin (1996) maintains the following:

For example, perhaps the ambiguity in legal principles relevant to the Computec case has caused problems for other companies; the participants might consider ways to clarify the law, such as working with their trade associations to promote legislation or to produce a model contract provision. In other kinds of disputes, parties might focus on improving, or transforming, communities (p. 22).

Through the example used by Riskin (1996) it is possible to show that the way in which the problem is focused (more or less narrow) does not necessarily depend on the type of case that the mediator is dealing with. In fact, Riskin (1996) uses the same case (a $ 30,000 dispute) to explain the different approaches that can be taken. Thus, a mediator with a very narrow vision of the problem will focus exclusively on the legal aspects (interpreting the scope of the contract, for example), whereas a mediator with a broader vision will focus on the commercial relationship between the parties (level II), to bring the parties to a process of forgiveness (level III), or even to reach an agreement that reports a benefit to the community (level IV). Consequently, the extent to which the problem is defined is not an intrinsic issue to each case, but will depend on what each mediator deems appropriate and efficient to resolve the issue.

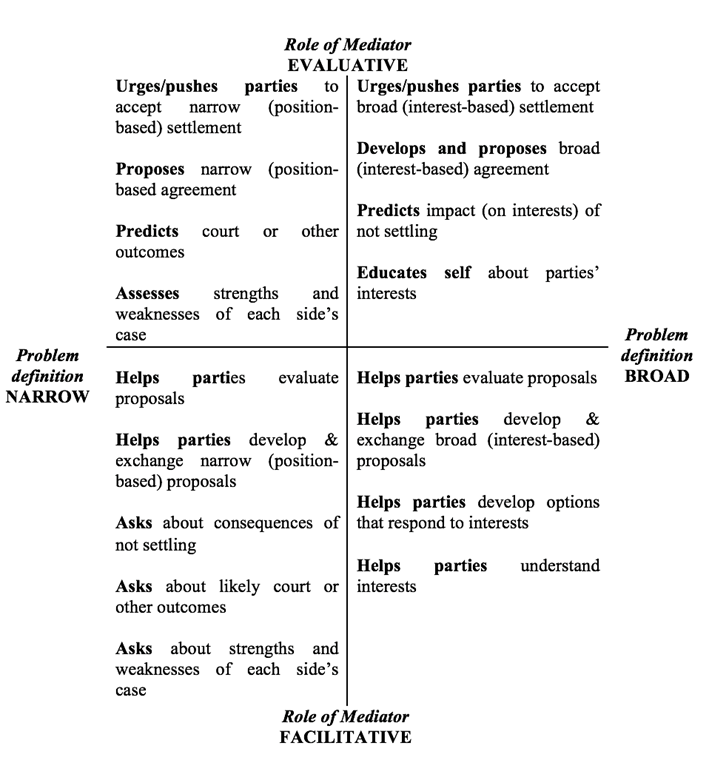

3.3. The four orientations in mediation

According to the style of the mediator -facilitative or evaluative- and the way in which it addresses the problem-narrow or broad-four different orientations are presented in mediation. It is essential to understand the particularities of each of these guidelines, as, as Jeffrey Krivis and Barbara McAdoo (2000) put it:

Understanding style is crucial to improving mediator performance. It allows a mediator to select from a spectrum of techniques that might be available depending on the nature of the issues presented. It also makes it simple for the mediator to explain to the disputants why a particular approach might be used in resolving the dispute.

It is for this reason that an analysis of the different combinations will follow: facilitating mediator with a narrow vision of the problem [3.3.1]; facilitating mediator with a broad vision of the problem [3.3.2]; evaluative mediator with a narrow vision of the problem [3.3.3]; and, evaluative mediator with a broad vision of the problem [3.3.4].

3.3.1. Facilitating mediator with a narrow vision of the problem

The facilitative mediator with a narrow vision of the problem tends to ask questions to the parties that allow them to reach a realistic perspective on what their situation is in the case of a possible litigation. However, it does not present its personal opinion or pressure the parties. Nor does it use the analysis of substantial documents within the conflict (the contract, for example). Its main strategy is to communicate with the parties through the elaboration of questions directed to the understanding of the litigious situation and the consequences of not reaching a negotiated solution (Krivis and McAdoo, s.f.). So

The facilitative-narrow mediator shares the evaluative-narrow mediator’s general strategy-to educate the parties about the strengths and weaknesses of their claims and the likely consequences of failing to settle. But he employs different techniques to carry out this strategy. He does not use his own assessments, predictions, or proposals. Nor does he apply pressure. He is less likely than the evaluative-narrow mediator to request or to study relevant documents. Instead, believing that the burden of decision-making should rest with the parties, the facilitative- narrow mediator might engage in any of the following activities (Krivis y McAdoo, 2000).

The main strategies used by a facilitative-narrow mediator are: (i) asking questions; (ii) assisting parties to identify their own interests from a legal perspective; (iii) assisting the parties to exchange proposals for solutions; and, (iv) assisting the parties in evaluating such proposed solutions (Riskin, 1996, p. 28).

As a consequence, this orientation is characterized mainly by the use of questions (facilitative) that are focused on legal aspects (narrow). The mediator then refrains from issuing a criterion or suggestion on the case and is limited to helping the parties identify their interests and options through the use of questions.

3.3.2. Facilitative mediator with a broad vision of the problem

For its part, a facilitative mediator with a broad vision of the problem tries to avoid that the parties within the conflict find themselves framed within their positions. On the contrary, it seeks to ensure that mediation takes place around the interests of those involved rather than their positions (Krivis and McAdoo, 2000). This goal is fulfilled through empathic listening and questions that help the parties explore their true interests as well as understand those of the other party.

The main tasks of this type of mediator are, (i) helping parties understand underlying interests, (ii) assisting parties in developing and exchanging broad interest-based suggestions for settlement, (iii) helping parties exchange proposals, and (iv) helping parties evaluate those proposals (Roberts, 2007, p. 198).

As in the previous orientation, this mediator also refrains from issuing his criterion and uses questions, as this is a characteristic of the facilitative style. However, in this case, the questions do not focus on legal aspects, but are intended to help the parties to identify their underlying interests, depending on the degree of extent to which the mediator addresses the problem, they will be commercial, personal or community focused.

3.3.3. The evaluative mediator with a narrow vision of the problem

Instead, the evaluative mediator with a narrow vision of the problem seeks for the parties to perceive their weaknesses and legal strengths within the conflict. The main objective is that through mediation, the parties can visualize their situation in a litigation. In this way they are made aware of the implications of not reaching a negotiated agreement (Riskin, 1996, pp. 26-27).

Unlike the facilitative mediator with a narrow vision of the problem, the evaluative mediator analyzes all relevant case documentation prior to mediation (Riskin, 1996, pp. 26-27). On the other hand, “most mediation activities take place in private meetings where the mediator will provide additional information and employ evaluative techniques” (1996, p. 27).

The main evaluative techniques, presented from the least to the most evaluative, are the following: (i) to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the case on each side; (ii) to predict judicial outcomes; (iii) to propose agreements on position-based commitments; and (iv) to urge the parties to resolve or accept a proposed solution (1996, pp. 27-28).

In conclusion, it is evident that the mediator adopts a more active position in the mediation process, because it is not limited to help the parties exchange proposals for solutions, but can even propose agreements. However, given that the mediator has a narrow vision of the problem, such agreements focus exclusively on legal and contentious issues.

3.3.4. The evaluative mediator with a broad vision of the problem

This type of mediator also seeks to help the parties to visualize what their situation would be if they fail to reach an agreement. However, it focuses on the potential satisfaction of interests, rather than the possibility of winning or losing in a judicial process. Thus, this mediator predicts how the interests of the parties could be met or not if no agreement is reached. Likewise, it proposes solution formulas that it believes could satisfy the interests of both parties. Therefore, this style requires that the mediator assimilates and actively reconciles the interests of the parties.

As Jeffrey Krivis and Barbara McAdoo (2000) put it, this mediator style “also provides predictions, assessments and recommendations. But she emphasizes options that address underlying interests, rather than those that propose only compromise on narrow issues”.

The main strategy of this style of mediation is to “learn about the circumstances and underlying interests of the parties and other affected individuals or groups, and the to use that knowledge to direct the parties toward an outcome that responds to such interests” (Riskin, 1996, p.30). Riskin (1996) explains that to achieve this, the evaluative-broad mediator uses the following techniques, from the least to the most evaluative: (i) to understand the underlying interests; (ii) to predict the impact of non-agreement on interest; (iii) to develop and offer broader options; and (iv) to urge the parties to adopt the proposal of the mediator or some other person (p. 30).

Indeed, similarly to the narrow-evaluative mediator, this mediator assumes an active role in mediation where it is ready to offer mutually agreeable options. These options do not focus on legal aspects, but on the interests of the parties.

Based on the different orientations studied, it is evident that there is no single type of mediator. On the contrary, depending on the orientation adopted by each mediator there are different techniques and strategies, and each one of them will aim at different objectives. With this in mind, we consider it extremely useful to provide the reader with a table drawn up by Leonard Riskin (1996, p. 35), so that the reader can better visualize and synthesize the qualities, strategies and objectives of different types of mediators:

3.4. Do the mediators move within the orientations?

The orientations of mediation are not static, either from the point of view of the development of mediation as a practice, nor from what a particular mediator does at a given moment.

Classical and pure mediation is a facilitative mediation with a broad vision of the problem. However, it is important to take into account the historical evolution (Kovach, quoted by Alenxander, 2006, and Folberg, 2015, p. 36)5 that this style of mediation had in the United States: one of the reference countries in mediation. Thus, in this country, over the years of practice, mediation has become evaluative with a narrow vision (Kovach, 2006, and Folberg, 2015, p. 36). This evolution reveals the possibility (and feasibility) of change in the mediator’s orientation.

In its general practice, each mediator tends to align to one of the orientations set forth above, but its orientation is never static. The mediator does not necessarily adhere to a given orientation for all procedures, and does not even use a single orientation at all stages within the same procedure. The different orientations are coupled to the different cases, depending on the contentious points, the relations between the parties, the future objectives of the same, etc. Also, each of the orientations may be more or less favorable at each stage of the procedure.

The mediator’s styles constitute a spectrum where mediators fluctuate, and are not necessarily polar opposites. Andrew P. Wyckoff (2000) explains that this spectrum between the facilitative-evaluative poles constitutes a large gray scale, in which styles are often difficult to distinguish. From an evaluative perspective, the mediator evaluates the facts and the potential results, in order to offer possible solutions to the controversy. From a facilitative perspective, the mediator helps the parties to evaluate the facts and the potential results, in order to generate consensual decisions (p. 6). Between these two perspectives, it opens the possibility of a series of combinations of attitudes and postures that can be assumed by the mediator. Likewise, the mediator can have a narrow vision of the controversy, managing an eminently distributive negotiation and yet incorporate an element that gives a certain amplitude to the problem, such as the confidentiality agreement.

The mediator’s orientation is often related to the attitude of the parties. A mediator tends to be evaluative when he notices that the parties want and wish to be provided with advice and guidance on the best alternatives to solve in conflict. Similarly, it does so when the parties trust that the mediator is qualified to provide such a guidance by virtue of their training, experience, objectivity, etc. On the contrary, a mediator tends to be facilitative when the parties seem willing and able to work with their counterparts, and when they can undoubtedly understand their situation better than the mediator and their own lawyers (Riskin, 1996, p. 19). It also tends to react to the definition of the problem presented by the parties and / or their lawyers.

Thus, the stage of the mediation procedure is a fundamental factor in the style that the mediator will adopt. “The styles of the mediator often evolve throughout the negotiation process, beginning with the facilitative and moving towards the evaluative” (DeVries, 2013). The evaluative approach implies a greater participation of the mediator, who intervenes to assess the situation of the procedure. Such intervention may not be desired by the parties at the beginning of a mediation; in stages in which the parties have not developed full confidence in the mediator, and therefore, they ignore the legitimacy of the mediator to provide an opinion. This is why timing or determining the appropriate moment to use the evaluative style is important. Urging parties to reach an agreement often becomes necessary, and doing so becomes more effective once a relationship of trust is established (DeVries, 2013). Mediator Michael Roberts (2002) agrees with this, and states that

In the early stages of a mediation, I tend to use a facilitative approach to help the parties work through the issues on their own and reach their own conclusions. Evaluative techniques are reserved until the later stages of the mediation when a rapport has been established between the mediator and the party. At this point the mediator’s opinions as to the validity of a party’s position and suggestions for settlement are more likely to be accepted. Most experienced mediators do not hesitate to evaluate the validity of a party’s position and offer suggestions for settlement at the appropriate time. Indeed, most parties expect it. The skill is in the knowing how and when to use both approaches.

4. Review of styles and definition of the problem in mediation in the city of Quito

The present research seeks to find the styles that the mediators of the city of Quito adopt, as well as the definition of the problem that they use in their work. It also pretends to find the expectations that lawyers have on these aspects, who come to mediation in the same city.

In this section we present the results of a quantitative research carried out through surveys, in order to identify the application of the guidelines in the practice of mediation.

4.1. Research Methodology

In order to identify the styles adopted by mediators and preferred by lawyers, as well as the approach with which the problem is defined, the present investigation was carried out with surveys for mediators and lawyers (separately) from the city of Quito. This research, replicated the methodology used by Jeffrey Krivis and Barbara McAdoo (2000) in “A Style Index for Mediators”.

The survey consisted of 31 statements to which the mediators and lawyers surveyed should have assigned a score between 1 and 10, with 1 being “strongly disagree” and 10 being “strongly agree”. 12 of the questions aimed to determine the style of the mediator, and 15 aimed to identify the extent to which they define problem. The remaining 4 questions referred to independent procedural techniques.

Surveys were sent to mediators and lawyers at a variety of mediation centers in the city of Quito. The purpose of involving both lawyers and mediators in the study is to compare their orientations and determine if what mediators offer is, in fact, what lawyers expect from the mediation procedures that they attend accompanying the parties. There was a participation of 35 mediators from different centers of the city and 54 lawyers which use these centers. Among mediator respondents, the institutional response presented by the National Mediation Center of the Judiciary (hereinafter CNMFJ, as its initials in Spanish) is included. This response motivated each of the statements with the official position of the Center. For this reason, mediators of CNMFJ not responded individually surveys.

Because of the size of the evaluated sample, the results of this initial study are merely exemplary and represent the preferences of the attorneys and mediators who answered the survey exclusively. Nevertheless, they allow us to obtain lights of preferences and general tendencies.

When answering the survey, giving a high score to style claims implies that the lawyer or mediator prefers an evaluative style, while assigning a low score reflects its inclination towards facilitative style. Similarly, giving a high score to problem definition statements means to prefer a broader vision of the problem, while assigning a low score reflects the preference for narrow vision. For didactic reasons, some questions were inverted so that participants could not identify the posture of assigning high or low scores and responding as objectively as possible. In these cases the scores were again inverted to correctly compute the evaluation of the final results shown in this paper.

The results obtained are presented in two main ways. The styles and definition of the problem are presented through comparative bar graphs that analyze the responses of lawyers and mediators to the most relevant questions (Sections 4.2, 4.3 and 4.5). Thus, one can observe the most frequently assigned scores by lawyers and mediators in each of the questions, and compare their preferences with respect to specific topics of mediation. In both cases, the results are presented on 5 points and not on 10 in order to make the existing trend clearer.

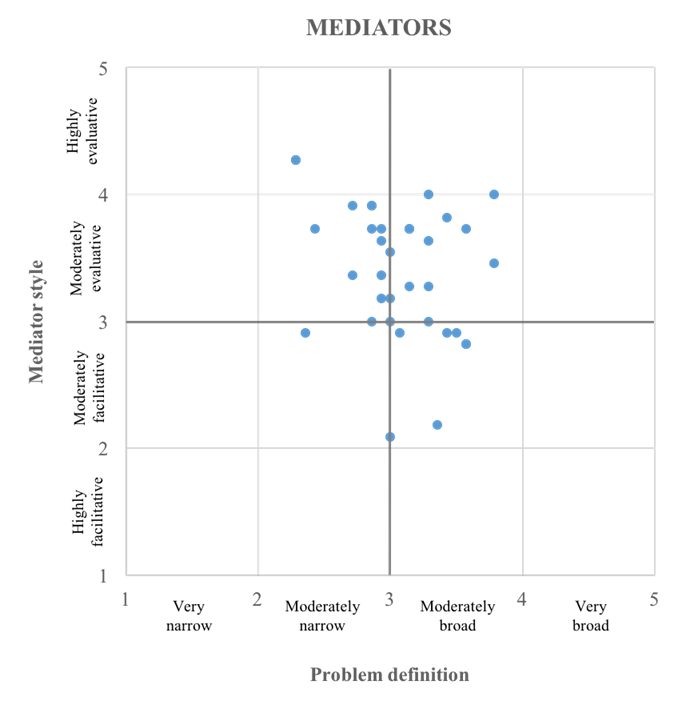

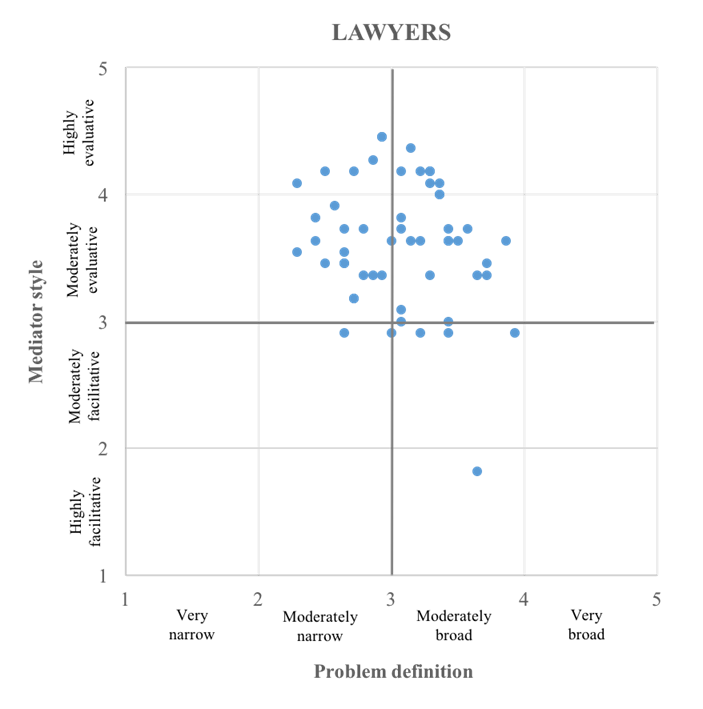

Finally, the orientations on mediation are reflected in a quadrant chart (section 4.4) in which each participating lawyer and mediator is located at a specific point in the quadrant. This reflects the preferences about the style of mediation and the definition of the problem. The quadrant in which each attorney or mediator is located is determined by obtaining an average of the ratings given to all of the survey questions. Likewise, the results are exposed over 5 points to show a clearer trend.

4.2. Mediation styles in the city of Quito

According to the results of the questions to be discussed later, most of the surveyed mediators reflect an evaluation style. The CNMFJ presents a different case, since it advocates for a facilitative style of mediation in its institutional response. Most of the surveyed lawyers also leaned towards an evaluative style of the mediator. We will now review the results to the most relevant questions that support this conclusion.

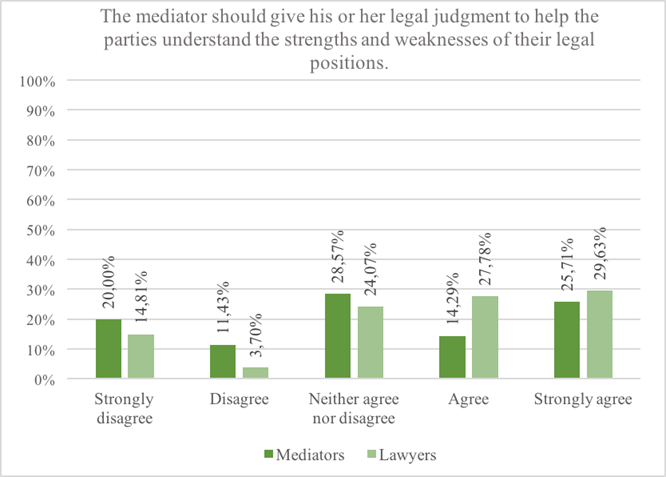

4.2.1. Issuing legal criteria

Regarding the possibility of mediators providing their legal criteria in order to help the parties to understand the strengths and weaknesses of their legal positions, 40% of the mediators favored this position and 31.43% were against it; while lawyers showed a much more definite trend, with 57.41% in favor of it and only 18.51% against it.

Comparative bar graph of the responses of mediators and lawyers to the question “The mediator should give his or her legal judgment to help the parties understand the strengths and weaknesses of their legal positions”

The mediators’ responses to this question reveal that there is no clear trend: there is a similar percentage between those who agree and those who disagree with giving their legal opinion. In fact, 28.57% of the mediators do not have a clear position on the matter, which implies a higher percentage than those who strongly agree or strongly disagree.

For its part, the CNMFJ leans towards a facilitative style, because its response is to be strongly disagree with the question, motivating this in the following way:

The manifestation of legal criteria is very close to giving an opinion, which is the task of a legal adviser or the report that could be made by an expert, specialist in the matter. This is not the task of the mediator, therefore, it always reveals to the parties the right that they have to go to the legal counsel provided by the State, through the Public Defender’s Office; or, private, according to the possibilities that the user might have, this is something that runs on their count. That is to say that the task of helping the parties to understand the strengths and weaknesses of their legal positions is a legal advisory task, which stands as contradictory with the mediator’s function of impartiality and neutrality. Now, from the approach of guaranteeing rights to which a public servant who provides a justice administration service, such as mediation, is subject by constitutional mandate, to respect and guarantee the rights of all users, as well as to the direct application of principles, that allow the full validity of the rights of the users. Therefore, it should be differentiated that the duty to inform users of the enjoyment of their rights and the one to comply with obligations, is opposite to the legal opinion resulting from a consultation, which is the task of a legal advisor (2016).

With regard to lawyers, there is a much more defined tendency towards an evaluative style, where most lawyers who attend mediation, in the company of the parties, seek for the mediator to issue their criteria in order to help them assess the weaknesses and strengths of their case.

It is interesting to recognize the difference that exists between mediators and lawyers, because while the second ones will seek a legal criterion, only a fraction of the mediators will be willing to meet such expectations. This invites us to question whether it would be appropriate for mediators in the future to favor a more evaluative style, or whether new methods of dispute resolution should be developed that offer an early neutral assessment, such as the ENA6, mini trial7 or rent a judge8.

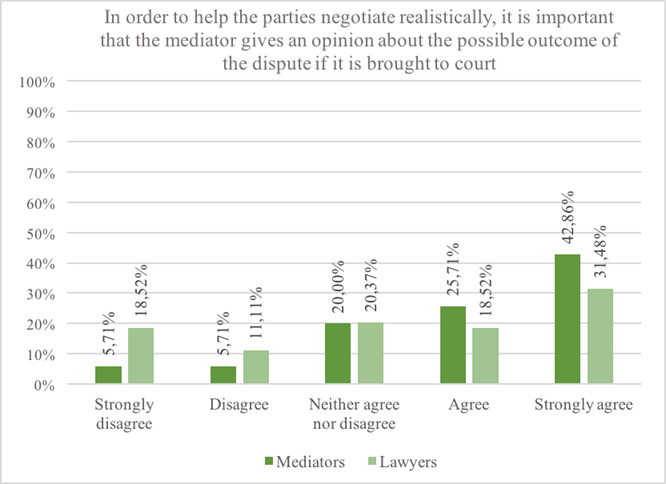

4.2.2. Predict the possible outcome in the judicial process

Regarding the fittingness of the mediator to pronounce itself on the possible outcome of the conflict if it were brought to the courts, 68.57% of the mediators favored it, while only 11.42% was opposed to it. Likewise, 50% of lawyers were in favor, while 29.63% were against.

Comparative bar chart of mediators and attorneys’ responses to the question “In order to help the parties negotiate realistically, it is important that the mediator gives an opinion about the possible outcome of the dispute if it is brought to court”

Mediators consider it useful and appropriate to anticipate possible outcomes of the case in court. Perhaps this relates to the role of the mediator as an agent of reality, which allows the parties to re-evaluate their positions. On the other hand, the CNMFJ had a neutral position although it recognized the value of this technique as follows: “according to the application of the linear method of negotiation, depending on the level of the conflict, the analysis of the Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (MAAN, in Spanish)” (2016).

Lawyers did not reflect such a clear trend. 50% showed a favorable trend, 20,37% took a neutral stance and 29,63% was against this. Although most lawyers tend for the evaluative style, with these results it would seem that lawyers do not trust the mediator’s prediction so much. It is interesting to compare the answers to this question with those of the previous question. While lawyers seek from the mediator a legal approach to assessing the weaknesses of their case, they would appear less than enthusiastic about the mediator anticipating the possible outcome in court.

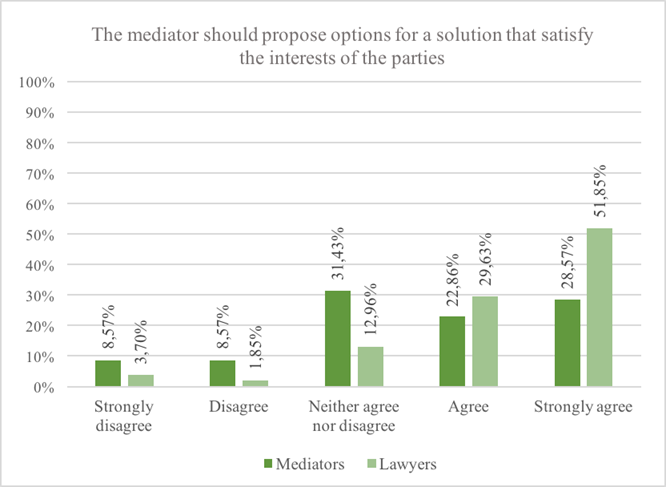

4.2.3. Make proposals for agreement

51,85% of the attorneys surveyed fully agree with a mediator that comes up with settlement options that satisfy the interests of the parties; while 28,57% of the mediators consider the same. 12,96% of lawyers and 31,43% of mediators do not have a clear tendency; while 3,7% of lawyers and 8,57% of mediators are in complete disagreement. In spite of the dispersion in these results it is shown that there is a favorable tendency towards the proposal by the mediator of options of solutions.

Comparative bar graph of the responses of mediators and lawyers to the question “The mediator should propose options for a solution that satisfy the interests of the parties”

Although the mediators’ results are more disperse than in the responses of lawyers, in both cases we can see an evaluative tendency. However, it is important to notice that lawyers are more in agreement that the mediator seeks for formulas of agreement, than the mediators themselves. In fact, in the responses of mediators 31,43% do not reveal any tendency, whereas in lawyers this value is only 12,96%.

Likewise, the percentage of lawyers who strongly agree with mediators who propose options in the procedure exceeds 50%, while in mediators this figure is only of 28,57%. This leads us to question how the practice of mediation will develop in the future. Maybe lawyers will seek mediators who propose solution formulas; or perhaps the mediators will adopt this technique in their practice with more regularity; probably reflecting the increasing adoption of an evaluative style, as it happened in the United States.

It is important to highlight the position of the CNMFJ, who pointed out that it strongly disagrees on the possibility of mediators proposing solution formulas, basing that decision as follows:

[T]he mediator does not suggest or propose options for solution, but helps the parties identify the best solution with which they would be willing to reach an agreement. There is a subtle difference between proposing or suggesting; and, helping the parties to reach this, the best solution to the conflict. First, it removes neutrality or impartiality, of the mediator, since it is an externalization of how the mediator considers the best way to resolve the conflict; while, secondly, it is the result of the application of communication tools and the task of empowerment that is a cross-cutting axis to the work of the mediator (2016).

This response indicates a clear facilitative tendency, since it is advised that suggesting options for settlement contravenes the neutrality and impartiality of the mediator. This concern is characteristic of mediators committed to a facilitative style.

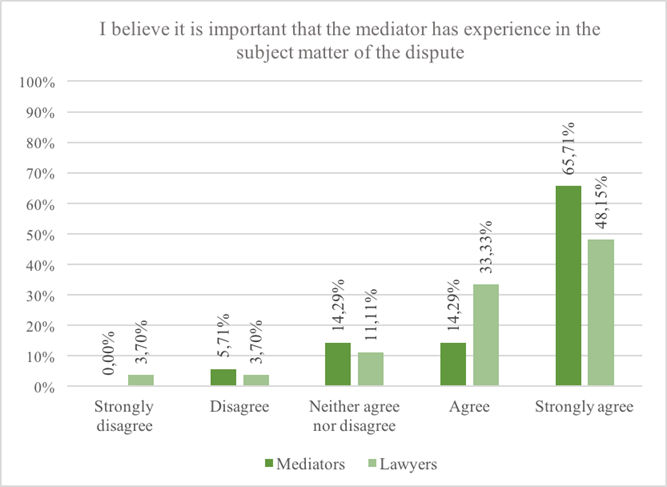

4.2.4. Specialization of the mediator

Regarding the need for mediators to be specialized, 65,71% of the mediators are in complete agreement and none of them strongly disagrees. As for lawyers, 48,15% fully agree, while 3,7% strongly disagree.

The evaluative style of mediation entails that the mediators know of the matter they are mediating; in this way they will be able to provide a better legal criterion, make more precise predictions, or present plausible proposals of solution. On the other hand, a facilitative style does not require specialization in the matter, but rather a proper use of techniques and strategies of communication and negotiation. The answers to this question confirm that the majority of the surveyed people, both mediators and lawyers give importance to the specialization of the mediator, a characteristic that is fundamental in any evaluative orientation. Likewise, the CNMFJ answered to be moderately in agreement, taking into account that:

It is necessary that mediators have a level of knowledge and experience suitable for the exercise of their functions. At the time taking a case, the study or analysis of the elements of the conflict, the mediator might have concerns, which will allow to identify the need for technical support, to strengthen their capabilities well in advance of the mediation hearing (2016).

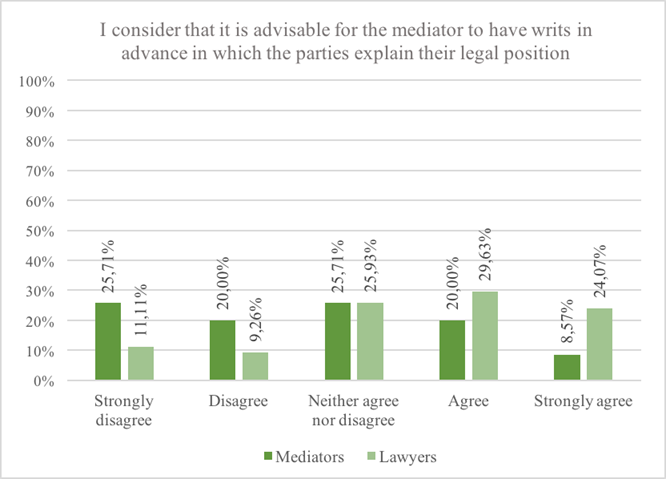

4.2.5. Access to legal positions before mediation

Finally, the respondents were asked about the convenience of having the mediator have writs in advance in which the parties explain their legal position. In this regard, 28,57% of the mediators were in favor of this. In contrast, 45,71% was opposed to it. Contrariwise, 53,7% of lawyers are in accordance to file writs in advance, while 20.37% are against.

Comparative bar graph of the responses of mediators and lawyers to the question “I consider that it is advisable for the mediator to have writs in advance in which the parties explain their legal position”

This question gives us insight on whether or not there is an inclination of lawyers and mediators in favor of premediation (Sher, 2012)9. Knowing about the documents or technical reports in advance to determine how to handle the case shows several reactions among the respondents. Being able to decide how the case will be handled involves a subject of structure and strategy, not a matter of decision making or positions in advance.

It can be evidenced that in the case of the mediators, in spite of dispersed results -in particular because 25,71% of the respondents do not have any preference- there is an unfavorable tendency against the possibility of having previous documents and reviewing them in preparation for mediation. This reflects a somewhat more facilitative vision on the side of the mediators, who perhaps imagine that it is better for the parties not to have definite positions that prevent the exploration of their real interests. Likewise, it allows us to show that mediators would not devote much time and effort to premediation.

In fact, the CNMFJ argued that:

it is not advisable for the mediator to have writs in advance in which the parties explain their legal position. Although the parties could present them, nothing prevents them from receiving them, however, the mediation hearing is the space provided for them to be able to express their criteria and interests (2016).

For their part, lawyers would prefer that mediators arrive prepared to the hearing by reviewing legal documents. It is interesting to see the discordance at this point, in which the service providers do not agree with the users of the service. Consequently, it is probable that the documents prepared by lawyers, with the aim of exposing the mediator to his perspective on the case, could be in many cases ignored.

These results are a call for attention to attach greater importance to the writs and documents prepared by the parties and to give value to the premediation phase.

On the basis of the carried analysis, it is possible to conclude that there is a general trend toward an evaluative style, as it can be seen from the table presented below in section 4.4.

Mediators reveal an evaluative trend, though not in an absolute manner; while lawyers express a clear preference for a more evaluative style. For its part, the CNMFJ shows a style of facilitative mediation, committed to the purity of classical mediation.

On the other hand, it is important to emphasize that there are certain issues in which there is no harmony between what lawyers would like and what mediators offer. This situation invites us to imagine how mediation will develop in the future and the techniques that mediators will adopt in their professional practice in order to meet the needs, expectations and preferences of the users. Similarly, several issues remain latent, such as the need to give greater emphasis to the premediation phase and the tendency to a greater specialization of the profession.

4.3. Definition of the problem in the city of Quito

Regarding the definition of the problem to be addressed, this research did not reach conclusive results. It would seem that both mediators and lawyers adapt to the definition of the problem that is most convenient to each concrete case.

We will now review the results to the most relevant questions that support this conclusion.

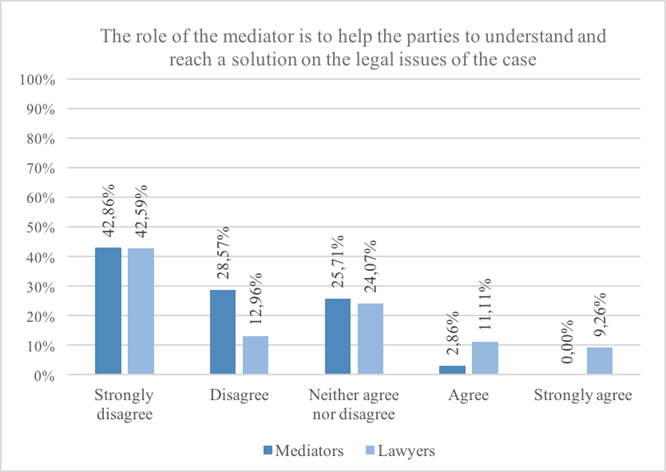

4.3.1. Focus on legal issues

A large number of mediators and lawyers consider that the role of the mediator is to help the parties understand and reach a solution on the legal issues of the case. 71,43% of mediators and 55,55% of lawyers show a favorable trend with this affirmation. Likewise, the CNMFJ fully agreed with this statement.

Comparative bar graph of the responses of mediators and lawyers to the question “The role of the mediator is to help the parties to understand and reach a solution on the legal issues of the case”

This means that for both attorneys and mediators, legal issues are part of mediation and that the mediator must contribute to the resolution of the specific legal dispute.

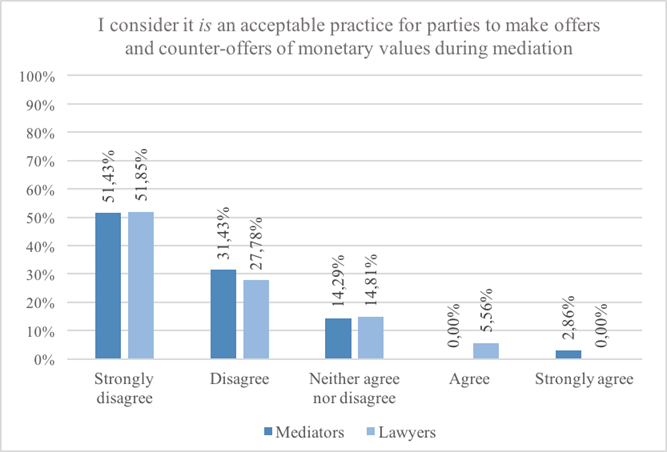

Additionally, most mediators and lawyers consider it an acceptable practice for the parties to make offers and counter-offers of monetary values during mediation. 82,86% of mediators and 79,63% of lawyers agree with this style of negotiation.

Comparative bar graph of mediators and attorneys’ responses to the question “I consider it is an acceptable practice for parties to make offers and counter-offers of monetary values during mediation”

This question has to do with the distributive bargaining model that sets aside the interests, emotions and causes of the conflict in order to focus only on an exchange of offers and demands for monetary content. This negotiation model is characteristic of a narrow definition of the problem. In this regard, the CNMFJ stated to be in full agreement:

According to the linear negotiation methodology applied during the hearing, the parties usually make offers and counter-offers, especially when dealing with civil, patrimonial or related issues with compliance of onerous or successive obligations. In any case, the use of bargaining as a form of agreement must be moderated by the mediator, reminding the parties of the objective criteria or causes that gave birth to the obligation in order to comply with the normative parameters in force at the time of the contract and the act of mediation (2016).

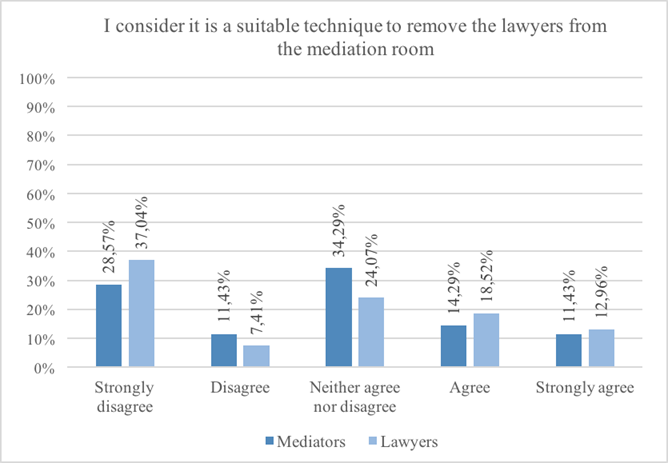

Finally, when asking the surveyed lawyers and mediators if they consider it a proper technique to remove lawyers from the mediation room, a clear response could not be obtained which shows a real trend. 40% of mediators (including the official position of the CNMFJ) and 44,45% of lawyers disagree; while a representative percentage of mediators and lawyers (34,29% and 24,07%, accordingly) did not take a stance; and finally 25,72% of mediators and 31,48% of lawyers agreed with the practice.

Comparative bar graph of the responses of mediators and lawyers to the question “I consider it is a suitable technique to remove the lawyers from the mediation room”

Despite the dispersion in the results, there seems to be a tendency to consider the presence of lawyers at the negotiating table as necessary, which in turn suggests that, the discussion focuses on legal issues.

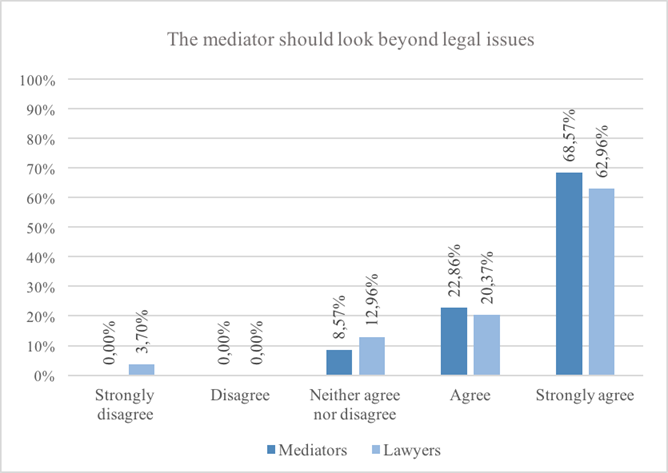

4.3.2. Focus on issues that transcend the legal matters

However, at the same time that the survey respondents agreed to deal with legal issues, they also agreed to address issues that went beyond the legal issue. Thus, 91,43% of mediators and 83,33% of lawyers surveyed agree to observe additional issues other than legal ones at the mediation process or when attending one.

This reflects a strong and evident tendency to define the problems brought to mediation in a broadly manner, so that it also takes into account the interests, the emotions and the perceptions of the parties.

In fact, the response of the CNMFJ reflects a definition of the problem that reaches the fourth level of amplitude, saying that:

the role of the mediator goes beyond solving cases, it also focuses on the search for a culture of peace [...]. [Citing] Dr. Gustavo Jalkh, President of the Consejo de la Judicatura, who states that the equation: a conflict equal to a judicial judgment is not viable or sustainable, social or economically, so mediation is a privileged way that allows the strengthening of the social composition and a significant saving of resources that should be invested in the formal judicial system (2016).

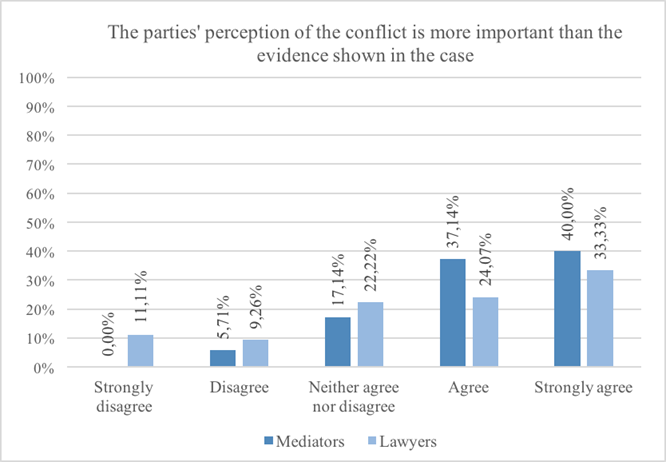

Likewise, both lawyers and mediators tend to agree with the idea that the parties’ perception of the dispute is more relevant than the evidence on the case. 77,14% of mediators and 57,4% of lawyers say they agree with the aforementioned position.

This reflects a tendency to define the problem more broadly, because the perceptions of the parties on the conflict will have more value than the evidence which they have to demonstrate their claims in a judicial process. This response seems to indicate that lawyers and mediators see mediation as a procedure that resolves disputes whose nuances are not exclusively legal.

Eventually, this could imply that neither mediators nor lawyers consider the possible risks, from the perspective of the evidence, when going to the courts.

The position of the CNMFJ is interesting in such a way that has adopted a neutral position recognizing the value of taking into account the analysis of reality, which implies that they leave the scope of perceptions, which is subjective, to address the issues based on objective criteria.

4.3.3. Focus on personal issues

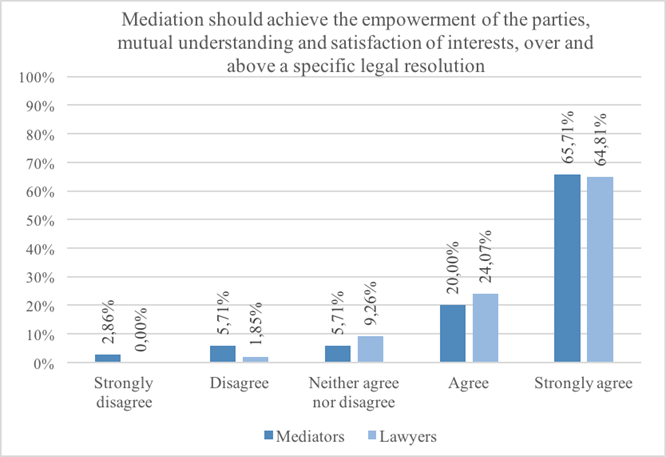

At the time of defining the problem, both lawyers and mediators, were also placed at the third level of amplitude. Thus, they considered that mediation should achieve the empowerment of the parties, mutual understanding, and satisfaction of interests, over and above a specific legal resolution. 85,71% of mediators and 88,88% of lawyers agree to incorporate these issues into the mediations.

Comparative bar graph of the responses of mediators and lawyers to the question “Mediation should achieve the empowerment of the parties, mutual understanding and satisfaction of interests, over and above a specific legal resolution”

It is interesting to observe the CNMFJ’s response, which strongly disagreed with this affirmation, arguing that:

they are not exclusive and independent objectives of mediation, empowerment of the parties, mutual understanding or satisfaction of interests but, if these objectives are achieved during mediation; the logical and natural consequence is that reached agreements resolve specific legal conflicts. Both are as important (2016)..

The result of the survey did not show a marked tendency with respect to the definition of the problem. When answering the questions, lawyers and mediators pointed to narrow and broad definitions of the problem at the same time. It is worth highlighting the position of the CNMFJ, that pointed out that one is as important as the other. Thus, the definition of the problem will depend heavily on the case before us and on how the parties wish to deal with the conflict. The mediators would seem to be moldable to any of the trends when defining the problem, so that they may respond to the expectations of the parties and their lawyers on this case-by-case basis.

4.4. The orientations of mediation in the city of Quito

With the survey, two scatter plots were obtained that reveal the general orientation of both lawyers and mediators. These summarize their preferences regarding the styles and definition of the problem. Both scatter plots reflect a marked tendency towards evaluative style, and a lack of clarity as to the definition of the problem. These results are plotted as follows:

4.4.1. Results of the surveys carried out with mediators

This quadrant reveals a clear tendency of mediators towards the evaluative style, since the vast majority of the results are located in the upper part. Regarding the definition of the problem, this graph shows us that there is no clear trend on how they define it, because the results are scattered along the horizontal axis.

4.4.2. Results of surveys of lawyers

As for attorneys, the trend towards an evaluative style is even clearer. In fact, with one exception, the only points below the horizontal axis are extremely close to the limit. Regarding the definition of the problem, as with mediators, there is no definite trend, since the results are scattered on the left and right sides of the quadrant regardless.

4.5. Other relevant procedural techniques employed in the city of Quito

Another component of the survey aims to identify other relevant procedural techniques used in mediation, such as the use of private meetings and the mediator’s contact with the parties before the hearing.

4.5.1. About private meetings

Some models of mediation are conducted exclusively in a joint hearing (especially mediations where the definition of the problem is broad); others, however, are carried out only in private meetings (especially mediations oriented to evaluative styles with narrow definition). Finally, other models combine both joint and private sessions with the objective to have a greater range of techniques available.

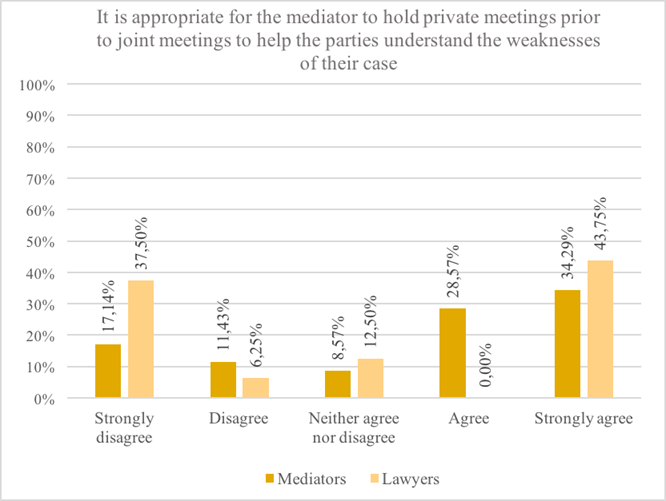

Of the respondents, 62,86% of mediators and 43,75% of lawyers agree to use private meetings with the parties prior to the joint meetings to help them understand the weaknesses of their case. In turn, 28,57% of the mediators and 43,75% of lawyers disagree with this practice.

Comparative bar chart of mediators and attorneys’ responses to the question “It is appropriate for the mediator to hold private meetings prior to joint meetings to help the parties understand the weaknesses of their case”

Consequently, there is no consensus on the appropriateness of using private meetings. In fact, the percentages of lawyers agreeing and disagreeing with the use of the practice are identical, indicating that their preferences are not uniform. Mediators, on the other hand, do show a favorable tendency to use private meetings. The CNMFJ agrees with the statement, motivating that:

Separate meetings are important and very useful, depending on the case; however, they are not the main tool of mediation. Therefore, the mediator should apply it, as many times as necessary, but it is designed in such a way that the parties can talk to each other because they have voluntarily come to the mediation hearing (2016)10.

These responses seem to reflect flexibility in the handling of mediation.

4.5.2. On the mediator’s contact with the parties before the hearing

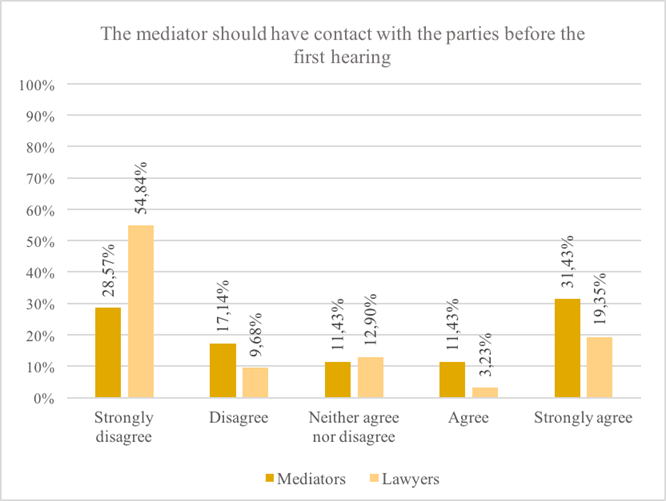

In the United States, mediation includes a stage of convening11, which implies that the mediator or its assistant “set the table” to negotiate. For this purpose, the parties are contacted prior to the hearing, among others, to verify who would attend, to confirm the date and place, to define the topics to be discussed, to agree on the possibility of presenting briefs with the legal positions of the parties, determine how the mediation will take place (whether there will be joint hearings, presentations by the parties or otherwise). This phase of pre-mediation has not been fully accepted in our practice. 42,86% of mediators and 22,58% of lawyers agree that the mediator should have contact with the parties before the first hearing. On the contrary, 45,71% of mediators and 64,52% of lawyers do not agree with this practice.

Comparative bar chart of mediators and attorneys’ responses to the question “The mediator should have contact with the parties before the first hearing”

Probably these results have to do with the fear of compromising the neutrality of the mediator. The CNMFJ has stated that it strongly disagrees with the statement, since it considers that: “it is a fundamental mission of the mediator to ensure neutrality and impartiality in the exercise of its task throughout the mediation process” (2016). Thus, the CNMFJ fears that previous contact with the parties may be detrimental and violates the neutrality and impartiality of the mediator, arguing that:

[I]t is not considered useful for the mediator to maintain contact with the parties before the first hearing, except for a telephone call or email that has its sole intention of confirming the parties’ attendance at the hearing of mediation (2016).

5. Conclusions

20 years have already passed since the promulgation of the Law of Arbitration and Mediation; and Ecuador has generated an important mediation practice. The present investigation sought to decipher the predominant orientation in mediation, preferred by both mediators and lawyers who attend the hearings. Many of the techniques that are used in mediation depend on this orientation.

The orientation of mediation is based on the style of the mediator (facilitative or evaluative) and the definition of the problem (narrow or broad). Originally mediation was conceived as a space where the facilitator enables the resolution of a conflict that goes well beyond the parties’ positions to focus on interests (broad definition). With time and the more active incorporation of lawyers into mediation procedures, practice has been transforming this initial vision to a more evaluative style and narrower definition of the problem. Today, mediators have a wide range of strategies and techniques that can be used to achieve dispute resolution at different levels.

For the present research, we conducted a survey for mediators and lawyers from the city of Quito, to generate an initial approach on what would seem to be the orientation that they lean towards mediation. The result shows that those who answered the survey demonstrate a clear tendency towards an evaluative style, with lawyers being even more evaluative than mediators. The institutional vision of the CNMFJ maintains a commitment to a more pure or initial style of facilitative mediation.

Likewise, respondents did not demonstrate a marked tendency with regard to the definition of the problem, evidencing total flexibility on the elements that can be part of the conversation within a mediation hearing.

Finally, there are some discrepancies between the expectations of lawyers and the practice of mediators. Besides, there are issues that will be unveiled with practice, such as the greater specialization of our profession in the future, which will include the pre-mediation phase and the emphasis that this will be given, and the possible use of private sessions over the joint ones. Time and development of mediation will shape these issues forward on.