Introduction

The crisis of the current civilization model

The ecosocial model in which society lives has been marked by an unprecedented growth in urbanization driven by a developmentalist approach (Peterson, 2017). This situation on the development model acquired special relevance as a result of what is stated in the report for the United Nations Our Common Future (United Nations [UN], 1987). While one section of the population has been alarmist about it, others have managed the matter with a certain banality due to their lack of concern (Rodríguez & Sugranyes, 2017). Despite this, the international community has heeded the issue with a greater or lesser relevance over the last decades, trying to address the discussion in accordance with the importance it requires (Caprotti et al., 2017).

The civilizing trend has been along this line of growth, transforming human settlements into metropolis models, resulting in a human development characterized by a disengagement with the natural world (Ciudades y Gobiernos Locales Unidos [CGLU], 2016). Therefore, the civilization model has been decoupling with what is natural, what is local and what is the community, under a mechanical thinking of autonomous growth and reproduction, weaving links at a global scale (Boström, 2012). This scenario acquired as a result of the industrial revolution, has been shaping a common model linked to an unsustainable form of development. Homogenous spaces have been raised where the identity of places has gone from being shaped by the uses and customs of a culture to being distinguished by their position in an economic-commercial ranking (Rodríguez-Pose & Griffiths, 2021). In this way, an urban, mechanized and homogenizing logic has expanded uncontrollably, transforming everything and generating enormous structural imbalances as a consequence (Liberal, 2011).

In Building and Dwelling, Richard Sennett (2018) raises the tension between the constructed city (the “ville”) and the lived city (the “cité”). On the one hand, there is what is physical, regulated and ordered, such as buildings, streets and squares, while on the other hand, relations are established with respect to ways of living, transit and appropriation of what is physical by citizens. This is worked deeply by Joan Subirats (2019), who sets the vision in which the built city and the lived city coexist. It is characterized by its diversity as a central value of the new era, to be taken into account in urban approaches that have to be flexible to face this scenario. The role of cities is therefore crucial when reflecting on a paradigm shift towards a sustainable civilizational model (Selman, 2017). Questions about our existence, “peace, diversity and sustainability finally realized and, for better or for worse, are resolved in cities” (Belil et al., 2012, p.16).

The new urban agendas emerge as tools to articulate strategies in this ecosocial transition in cities. Since the publication at the international level of the New Urban Agenda (UN-HABITAT, 2016), the different levels of governments, such as the European, national and regional levels, have been developing their own framework agendas. This issue is part of a more complex process to transform the current civilizational model into a new sustainable paradigm, in which human settlements have a significant relevance (Borja et al., 2016). This is taking place within a global framework shaped by the 2030 Agenda with 17 Sustainable Goals, where Goal 11 is the one that presents this urban issue (Rey Pérez, 2017; Valencia et al., 2019).

Related to the relevance of the regional level, Andalusia has 8,472,407 inhabitants in 2021, making it the most populated region in Spain, and with an area of 87.599 km² it is the second largest region in the country (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], n.d.). It also has a system of cities that enriches and increases the complexity of the scenario. This is formed by the Regional Centers, the networks of Medium-sized Cities and the Networks of Settlements in Rural Areas, where the cities of Seville and Malaga are positioned among the 6 most populated cities in Spain. (INE, n.d.). To this territorial context is added its heritage value, being the region in Spain with more World Heritage Sites declared (UNESCO, n.d.). Nevertheless, its social reality also presents relevant issues such as unemployment, since according to the Urban Indicators Report in (INE, n.d.), seven Andalusian cities are among the top ten cities with the highest unemployment rate in Spain.

To address these changes in the urban model, Andalusia has created its Urban Agenda with the aim of becoming an instrument for territorial, economic, social and environmental development in the region, relying on the potential of cities as benchmarks in the design and implementation of public policies. (Suárez Samaniego, 2019). By understanding these documents as a reference framework for the sustainability of our cities, the relevance of this research becomes visible. And this broadens the perspective beyond the three pillars that make up corporate sustainability, such as those that are economic, social and environmental (Purvis et al., 2019). The current debate reflects the need to contemplate the role of heritage and citizenship in order to understand the position of the cultural pillar in the discourse of sustainability (Sabatini, 2019).

An approach to the new urban agendas

Understanding the issue from a holistic view of the set of documents and not as single and independent objects, it is worth highlighting the alignment and complementarity of the agendas at different levels (Huete García et al., 2019). It is understood that the achievement of the objectives assumed and the mechanisms established in them manage to cover the issue from more generic aspects, such as the New Urban Agenda, in terms of the transfer of good practices, training, etc. (Chatterji, 2021).

As the scale of the Urban Agenda of the European Union decreases, more concrete realities begin to be defined and initiatives for implementation emerge, such as the case of Partnerships. It intends to generate synergies between member states, cities and other actors, to work on very concrete issues (Employment and local economy; Urban mobility; Housing; Sustainable use of land and resources; Climate change; Air quality, etc.) (Hernández Partal, 2017).

Related to the Spanish sphere, it is interesting to mention the reception that the New Urban Agenda has had once it has reached the national scene. As it seems that, by entering a more delimited territory with a more defined reality, both the Spanish Urban Agenda and the technicians that oversee applying this instrument in cities benefit. On one hand, the Spanish Agenda sees itself better able to define strategy aligned with a more concrete diagnosis. On the other hand, the technicians who find in the national document information with a greater concreteness and feasibility of practical application than the international agenda of Habitat III. (de la Cruz-Mera, 2019).

In a general comparative analysis of the documents referred to above (Huete García et al., 2019), considering the coherence of their contents, it is observed there is a certain similarity in their content. Despite there being different backgrounds in the elaboration of each agenda, there seems to be a single model underlying all of them. They also affirm that in their materialization there are divergences between them, but with a certain logic due to the approach from the different levels of government, considering that there is a coherent complementarity between them.

In this way, the new urban agendas intend to serve as a reference to articulate the urban policies of those local authorities that really want to make a commitment to sustainability (Verdaguer Viana-Cárdenas, 2017). The regional urban agendas, as the closest level of government to the cities, play a fundamental role in the transcription of the guidelines proposed by its predecessors before its application at the local level. In this sense, some case studies close to this research can be found, such as the Urban Agenda of Málaga (De Gregorio Hurtado, 2019).

According to what has been studied by various authors so far, cultural heritage in the new urban agendas plays multiple roles, generally transversal to the agendas themselves. In no case it is treated as one of the fundamental principles of the agendas, but as a tool or mechanism for the achievement of challenges to which greater relevance is granted (De Frantz, 2022; Del Espino Hidalgo, 2019; Garschagen et al., 2018; Rey Pérez, 2017; Ripp & Rodwell, 2016). Thus, the basis of this research is characterized by the understanding of the duality that exists in cities, where heritage and citizenship are considered key factors to articulate the analysis of new urban agendas from a cultural approach.

About heritage

The concept of heritage has been presented since the origins of the sustainable development concept, being outlined in the Brundtlant Report “this task of understanding that we are the key piece in a chain, receiving a heritage from the past and that it will be transmitted to the future’’ (UN, 1987, p. 23).

After working from the beginning on a concept of sustainable development made up of three pillars -economic, social and environmental-, academics are proposing to broaden this to include a fourth pillar, what is cultural (Hawkes, 2001). The Hangzhou Declaration (UNESCO, 2013), whose aim is to place culture at the heart of sustainable development policies, entails the first recognition at the global institutional level where heritage values are strongly linked to the challenges of the future.

These new approaches must fully recognize the role of culture as a value system and as a resource and framework for achieving truly sustainable development (Pintossi et al., 2023). Furthermore, the need to consider the culture as a source of creativity and renewal, learning from the experiences of previous generations and the recognition of culture as part of the global and local commons (Rey-Pérez & Pereira Roders, 2020; UNESCO, 2013; Veldpaus et al., 2013).

These new concepts have established the paradigm where culture and heritage have become driving instruments for sustainable development at the disposal of public administrations and international organizations (Rius-Ulldemolins et al., 2015). This means relying on the new urban agendas as a vehicle to collaborate with citizens in creating a sense of community and enhancing the value of their assets (Lee, 2016).

About citizenship

Citizen participation, as a link between the built and the lived cities, is a key to establishing a working methodology for rethinking the city (Donadei, 2019; Dubois et al., 2023). Moreover, it is essential for the elaboration and development of new urban agendas specially when they reach the local scale. This participatory approach is accompanied by necessary issues rather than favorable ones when developing a new city paradigm (Alberich, 2009).

In addition to giving citizens the opportunity to participate in the design of their new cities, this will influence the safeguarding of local heritage. Besides, it will favor the increase in the quality of democracy at the local level since these practices encourage the empowerment and involvement of people in the affairs of their locality (Rivero Moreno, 2019).

It starts from the premise that the new urban agendas provide the necessary support for local governments to have a useful tool when planning actions in the city. The alliance between local administration and citizen participation is imperative to promote the implementation of the agendas, based on the co-responsibility of citizens in the social construction of the habitat, through transformational participation initiatives (Dávalos González & Romo Pérez, 2017). Therefore, due to the importance of the local level as a scale where citizens acquire a leading role, it is of interest to investigate the application of these new urban agendas on the closest scale of a concrete reality for his application.

Methodology

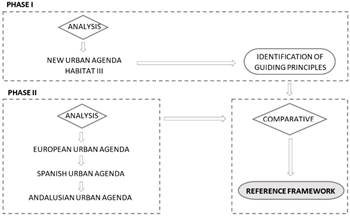

In this context, the aim of this research is to elaborate a reference framework for the implementation of the new urban agendas from the vector of heritage and citizenship, approaches that are facilitators and drivers of economic, social and environmental dimensions, forming the pillars of sustainability. (UNESCO, 2017). Consequently, the methodology applied throughout the research is composed of the following phases, in order to constitute the reference framework:

Phase I_ Analysis of the role given to heritage and citizen participation in the New Urban Agenda presented in Habitat III (UN-HABITAT, 2016), as a primary document. This review provides an identification of principles and/or strategies, dealing with heritage and citizenship, included in the Agenda. These main topics outline the most relevant aspects to be considered in order to achieve a sustainable city model.

Phase II_ Analysis of the dimension given to heritage and citizen participation at the European level with the Pact of Amsterdam (European Union [EU], 2016) and the Bucharest Declaration (EU, 2019), at the national level with the Spanish Urban Agenda (Ministerio de Fomento, 2019) and at the regional level with the Andalusia Urban Agenda 2030 (2018). This analysis achieves a deep vision of the matter since it is capable of uniting and making jointly visible the objectives/challenges related to heritage and citizenship of the different scales of governance in their respective Agendas.

Finally, in order to outline a common reference framework, a discussion is developed based on the comparison between the different documents analyzed, where the alignments and disparities between the different levels of governance become visible. This comparison allows us to obtain a multilevel vision on the role of heritage and citizenship in a new paradigm of sustainable cities. This framework determines a series of items from a cultural approach that will be a reference for local urban agendas as guiding principles for their action plans.

Results

The heritage and citizenship approach in the New Urban Agenda

As the international representation of the urban agendas, the NUA is presented as an example of multilevel participatory design and states in its first paragraph “with the participation of subnational and local governments, parliamentarians, civil society, indigenous peoples and local communities, the private sector, professionals and practitioners, the scientific and academic community, and other relevant stakeholders, to adopt a New Urban Agenda” (UN-HABITAT, 2016, p. 3).

The NUA highlights the interrelation between social and cultural aspects, considering them as axes of sustainability along with the economy and the environment. Cultural diversity is recognized as a source of enrichment for humanity, with a dedicated section emphasizing the importance of culture in promoting new sustainable consumption and production patterns. The text explicitly connects heritage to the sustainability of cities, advocating for integrated policies and investments at various levels to safeguard and promote heritage expressions. In the Action Plan, cultural heritage is shown as a potential resource for achieving urban sustainability goals, aligning with local discourse through activities such as heritage conservation, cultural industries, sustainable tourism, and the performing arts.

Participation is emphasized, treating citizens as essential stakeholders and promoting the inclusion of diverse groups, such as women, young people, and people with disabilities. The text advocates meaningful participation, recognizing the key role of children and young people in the process of change. The document promotes the building of urban governance structures, emphasizing the integration of age and gender participatory approaches throughout processes. An effective implementation requires civil society training, transparent information sharing from administrations, and efficient management of information resources.

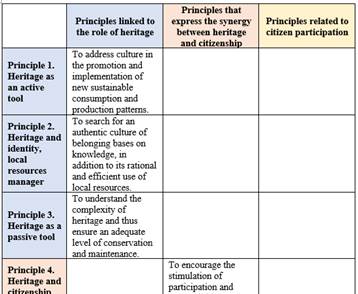

After reviewing the document, seven principles have been identified and shown in the Table 1 as a reference framework in relation to the role of heritage and citizen participation, confirming their importance in urban planning strategies and approaches in order to shape a sustainable city model. The first three are directly linked to the role of heritage, followed by one that expresses the synergy between heritage and citizenship, and finally three other factors directly related to citizen participation.

Source: Authors (2023)

Table 1: Summary table of the heritage and citizenship principles in the New Urban Agenda of Habitat III.

1. Heritage as an active tool. Using culture in the promotion and application of new sustainable consumption and production modalities, taking heritage to carry out urban regeneration operations in order to address such actions in a comprehensive manner thanks to the capacity of culture to build links between the collectives that inhabit them and generate a sense of belonging.

2. Heritage and identity, local resources manager. In the search for an authentic culture of belonging based on knowledge, as it is grounded on the premise of the capacity of intangible cultural heritage to promote local identity, and that it is added to the rational and efficient use of local resources, such as the economy and tourism.

3. Heritage as a passive tool. From the complexity natural and cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible, to safeguard and promote cultural infrastructures and sites, museums, indigenous cultures and languages, as well as traditional knowledge and arts, and thus ensure an adequate level of conservation and maintenance.

4. Heritage and citizenship work together. As a stimulus for participation and responsibility, with an emphasis on promoting its incorporation into the education of the young population and children, basing a future urban model on the concept that the city is the most complex cultural product elaborated by society in a collective construction.

5. Participation of all citizens. Including local governments, the private sector and civil society, women, youth, people with disabilities, indigenous people, professionals, academic institutions, trade unions, employers’ organizations, migrant associations and cultural associations.

6. Participation throughout the process. Using participatory methodologies such as workshops or forums, allowing involvement from the beginning and on an ongoing basis, from the formulation of concepts to their design, budgeting, implementation, evaluation and review.

7. Proactive citizenship in governance. Generating digital governance instruments focused on citizens in a way that broadens participation, promotes responsible and coordinated governance, thus increasing efficiency, transparency and favoring multilevel governance, in which the different administrations carry out their tasks and functions in an effective and coordinated manner and with citizen participation.

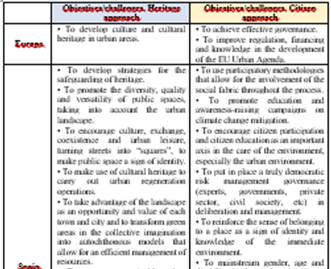

The heritage and citizen approach in the New Urban Agendas of Europe, Spain and Andalusia

European Union

At the European level, the Pact of Amsterdam establishes the Urban Agenda of the European Union (EU, 2016). It contains twelve priority themes for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. To these, eleven more objectives are transversally added to try to cover the issue from the broadest possible viewpoint.

It is worth highlighting the absence of cultural heritage in both the priority objectives and the transversal objectives, not even being mentioned in any part of the document, blurring the importance given to it in the NUA. However, citizen participation is acknowledged in one of the transversal objectives, highlighting its significance for effective governance. As the document progresses, a section dedicated to participatory synergy among civil society, knowledge-based institutions, and businesses is introduced, emphasizing better regulation, financing, and knowledge dynamics for the future development of the EU Urban Agenda.

In 2019, the Council of the European Union released the Bucharest Declaration (EU, 2019), aiming to revise the previous declaration and addressing its shortcomings. A significant update includes the addition of two new complementary themes, with one of them focusing on Culture/Cultural Heritage. The declaration underscores the commitment to effective implementation of participatory methods, seeking further efforts to enhance results through consolidated participatory approaches outlined in paragraphs 14 and 43.

Spain

Spanish Urban Agenda goes a step further and works under a more conscious and democratic participatory model (Ministerio de Fomento, 2019). Affirming that the document itself has been elaborated from the bottom up, as recommended by international agendas, considering the contributions of all the key actors for urban development. The inclusion of heritage and citizen participation in seven out of ten strategic objectives included in the document reflects the importance given to these approaches.

Regarding heritage, the Agenda focuses on organizing the territory, rational land use, and heritage conservation. It promotes a culture of knowledge-based belonging and highlights the cultural complexity of cities, considering them as the most complex cultural products developed collectively by society. The Agenda intertwines heritage and citizen perspectives in addressing urban sprawl, climate change impacts, and promoting social cohesion. Economic objectives emphasize the support and use of local heritage for sustainable urban economies, particularly through sustainable tourism.

The importance of citizen participation is stressed, especially in the context of digital innovation, encouraging governmental management that involves citizens in urban issues. The national urban agenda proposes a governance model update, emphasizing transparency, education, and consolidated citizen participation. To enhance participatory power, the document suggests factors like a participatory procedure for citizens before formal planning, accessibility to information, and fostering a culture of citizen participation considering human diversity and a culture of conservation. Overall, the Spanish Urban Agenda emphasizes heritage, citizen participation, and sustainability in urban development.

Andalusia

The Andalusia Urban Agenda formulated at the regional level aims to serve as a reference instrument for the urban and territorial development of the region, acknowledging its complexity and vastness (Consejería de Medio Ambiente y Ordenación del Territorio, 2018). The document outlines fifteen challenges within five dimensions: spatial, economic, social, environmental, and governance. Heritage and citizen participation are highlighted in the spatial, social, and governance dimensions.

In the spatial dimension, the challenge of promoting a sustainable and integrated city includes strategic lines emphasizing public spaces, facilities, and urban and territorial heritage. This holistic approach values Andalusia's cultural and natural heritage, incorporating landscape heritage and traditional settlement patterns. An action axis focuses on promoting and protecting cultural and natural heritage as a basis for a sustainable habitat, recognizing its social, cultural, and economic importance.

The social dimension underscores total participation, emphasizing the involvement of all segments of society. Challenges related to designing the city for all people and promoting an equitable city highlight the diverse participation of citizens, explicitly mentioning women, young people, the elderly, and people with functional diversities in citizen participation processes.

In the governance dimension, citizen participation is fundamental to the new transversal paradigm of leadership. The challenge of an administration with leadership focuses on strategic vision, with three action axes emphasizing the need for a participatory plan, a reformist administration through consensus and accountability, and a governance model involving alliances between administration, citizens, and the private sector.

As a result of this comparative analysis, the identified objectives/challenges from the perspective of heritage and citizen are shown in the Table 2. Therefore, this allows us to observe and to understand how these approaches are considered from each level of governance in order to implement the international strategies in more specific contexts.

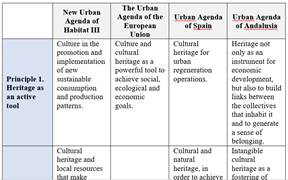

Discussion and conclusions

As a result of the analysis, the alignment of the Spanish Urban Agenda and the Andalusian Urban Agenda with the seven principles previously identified in the New Urban Agenda of Habitat III is confirmed. In their texts, as the governance scale moves down, it increases the level of concreteness of the role of heritage as an active, passive and identity tool; the synergy that the conjunction between heritage and citizenship implies; and the relevance of citizen participation in the process. In contrast, this raises awareness of the lack of this content in the European Urban Agenda, which only addresses three of the seven principles identified, although it does so by applying a renewed vision of these concepts. These results can be clearly seen in the comparative Table 3.

Source: Authors (2023)

Table 3: Comparative table of the heritage and citizenship approach in the cases analyzed

Therefore, despite being constituted as framework documents within the same horizon, each agenda has a different character depending on the scale at which it has been drawn up. This intention, although it can be seen as negative due to the lack of alignment of certain aspects between the agendas, is understood rather as a reason for complementarity. It is owing to the fact that there are issues that might not make sense to deal with at a given level of government, whereas, if they are treated on at the appropriate scale, they could have the necessary importance within the general framework of the urban agendas.

In this sense, it shows how the NUA at the international level assumes the role of a global starting document, setting out the general guidelines for the implementation of the criteria proposed for the sake of a sustainable city model. Because of its global nature, it addresses the issues in a generic way, without going into more detail than its scope of intervention allows, but it does put on the table the points that must govern the successive agendas when they approach a more concrete reality. Thus, it can be seen that throughout the document, the aspects highlighted are expressed on numerous occasions by way of a summary. And the fact is that in some way, it is necessary to value the effort involved in capturing in a document the amalgam that the debate on the sustainability of cities entails, even more so in the face of the enormous diversity of an international panorama.

On a second level is the European Agenda, and this is through the Pact of Amsterdam, which, focuses on three fundamental pillars of European policies: better regulation, better financing and better knowledge. But analyzing its content in terms of heritage and citizen participation, the lack of content in this respect in the document is striking, mentioning only the importance of participation.

For this reason, the content of the Bucharest Declaration is subsequently reviewed, including priority issues that were absent from the list presented in the previous edition, as the importance of cultural heritage in sustainability strategies. Even so, at this European level, the same grade of involvement with heritage issues and participation is not detected, which may be due to the focus of the latter’s efforts on other issues, such as the conception and management of partnerships between European countries.

At the national level, the Spanish Urban Agenda not only aligns itself with the issues raised in the international guidelines, but also makes a leap in its perception of reality and begins to propose the effective application of all the theory contained in the previous agendas. This Agenda includes the seven key principles identified in this research, some of them expressed in a similar way to the NUA of Habitat III, and others show an intentionality that evidences a knowledge of the Spanish reality.

However, even at this scale, it is difficult to establish guidelines that affect the whole country in the same way due to the diversity of contexts. For this reason, the Spanish Agenda develops a broad and detailed application criterion, alluding to the role of the local administration as the main actor and responsible for the implementation of the strategies. Since this is the articulating element between the theoretical bases collected in paper format and the actions materialized in a real and tangible scenario.

The regional level has been the last one analyzed to establish this theoretical framework. In this respect, Andalusia Urban Agenda is presented with a high level of maturity and solidity, as it is capable of gathering all that has been presented by its predecessors and focusing it on the reality of the Andalusian territory. This means the key to propose strategies whose implementation could influence directly in the territorial network, due to the fact of being the government immediate level of the system of cities or nodes that make up the Andalusian geography. With which the importance of a good approach by the regional government becomes fundamental, as a prior step to local action. So that this could provide a system that functions as a basis for a more sustainable model of the city and its relations within the networks of flows that occur in the region.

In this way, the important consideration that the heritage and citizenship approaches acquire in these documents become visible. Both approaches constitute the cultural pillar, which is the fourth of the pillars that make up sustainable development. Heritage and citizenship are presented as articulators of the economic, social and environmental aspects in the strategies exposed by the new urban agendas, which is a reference framework for local administrations in relation to the implementation of such strategies.

With this documentary review of the new urban agendas, a reference framework is established in which to lay the foundations for the role of heritage and citizen participation approaches in the debate on the sustainable city model. In order to establish the most complete criteria possible, from a global vision to a more contextualized view, the agendas elaborated at different levels of government have been considered, such as international, European, national and regional levels.

The next level of study corresponds to the local one as the last link in the chain of government. Many cities are currently developing their local Urban Agenda, taking their predecessors as a reference point. We are therefore faced with the situation that, depending on the degree of depth and stringency with which they implement the guidelines exposed in the general documents, this will be reflected in the consideration of culture as an articulating axis where heritage and citizen participation are the backbone of the proposals made.

To conclude, it is worth highlighting the key principles that have been identified, in terms of heritage and citizen participation, in order to institute a sustainable city model. However, to guarantee the implementation of this framework, it must be ensured that technicians and professionals are aware of the importance of this, being responsible for applying a matrix of proposals in their respective areas that verify the compliance with the seven key principles. This understanding makes visible the need and the potential to analyze local case studies that allow us to approach a scale in which can be assessed how this transition from theory on paper to materialization takes place.