INTRODUCTION

Three forms of anterior midline intracranial cava have been recognized, the cavum septum pellucidum (CSP), the cavum Vergae (CV) and the cavum vellum interpositum (CVI). Current knowledge suggests that CSP and CV are not related to the ventricular cavities as they do not contain cerebrospinal fluid nor do they have ependymal lining. CVI is considered a subarachnoid cistern that communicates with the quadrigeminal cistern and the cisterna magna.(1)(2)

CSP and CV are often present in newborns and infants (as part of the normal embryo-fetal development) but their prevalence decrease during the first year of life. However, persistence of these congenital cava may be observed in young adults or even later in life, probably as a signature of limbic system dysgenesis.(3) In addition, cases of acquired cava may be observed among professional boxers, fighters and survivors of repeated traumatic brain injury.(4)(5)

Prevalence of midline cava among young and older adults varied across studies.(6) Such differences are likely related to characteristics of study populations. Data on the prevalence of these cava in the population at large is unknown, since most series are not based on healthy individuals taken from the community.(7) A recent meta-analysis comparing prevalence of CSP across patients with mood disorders versus healthy subjects found that 293 out of 630 controls (46.5%) included in nine studies had CSP, which is likely an overestimate.(8)

Some studies found that persistence of CSP and/or CV into adulthood is associated with mood disorders and other psychiatric conditions.(9)(10)(11)(12) As part of the limbic system, the septum pellucidum has a role in the connection between hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, the trigonum habenulae, and the brainstem reticular formation, thus, providing a pathogenetic rationale for the association between persistence of congenital brain cava and various psychiatric disorders.(13) Other studies, however, found no relationship between midline cava and mood disorders.(14)(15)

In this study, we aimed to assess the prevalence of CSP and CV in a cohort of individuals aged ≥20 years, and to assess their association with clinical depression. Individuals with CVI were not included in view of the lack of relationship between this cavum and psychiatric disorders.

METHODS

Study population

This study was conducted in Atahualpa, a rural Ecuadorian village. The population is homogeneous regarding race/ethnicity (Amerindians), living conditions, socio-economic status and dietary habits, as previously described.(16)

Study design

Using a population-based design, we identified Atahualpa cohort individuals aged ≥20 years with a CSP and/or CV (case-patients) by means of a head CT. All identified cases were matched 1:1 by age (±2 years) and sex to individuals without evidence of midline cava (control subjects), in order to assess potential associations with symptoms of depression by use of the McNemar’s test and conditional logistic regression models. The study followed the recommendations of the standards of reporting of neurological disorders (STROND) guidelines,(17) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital-Clínica Kennedy, Guayaquil, Ecuador (FWA 00006867). All individuals signed a comprehensive informed consent form before enrollment.

Neuroimaging protocol

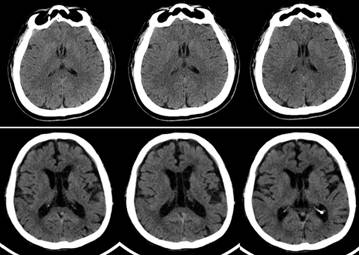

CTs were performed with a Philips Brilliance 64 CT scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at Hospital-Clínica Kennedy, Guayaquil. Slice thickness was 3mm, with no gap between slices. Readings focused on the presence of CSP and CV on axial scans. CSP was defined as a structure located between the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles having as the anterior boundary the genu of the corpus callosum and as the posterior boundary the columns of the fornix (Figure 1, upper panel). CV was defined as a structure located between the lateral ventricles having as the anterior boundary the body of the corpus callosum and as the posterior boundary the crus of the fornix (Figure 1, lower panel). All images were read by two raters blinded to clinical information. Inter-rater agreement of CT lesions of interest was excellent (k=0.92); discrepancies were resolved by consensus. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 Unenhanced CT of a study participant with a cavum septum pellucidum (upper panel) and with a cavum Vergae (lower panel), showing the typical anterior and posterior boundaries of these midline cava.

Selection of control subjects

Individuals with no evidence of CSP or CV on CT were selected as potential controls by the use of the Random Integer Generator (https://www.random.org/integers/) and then matched 1:1 by age (±2 years) and sex to patients with CT evidence of these cava. Subjects were ordered according to their unique 7-digit code used for enrollment in the Atahualpa Project. If a given randomly selected individual did not match with the corresponding case-patient or did not agree to participate, the next on the list (also matched by age and sex with the corresponding paired case-patient) was chosen.

Psychiatric evaluation

Both case-patients and control subjects were interviewed by a board-certified psychiatrist blinded to the case-control status. The psychiatric interview focused on the application of a widely used screening instrument to detect depression in primary care settings, the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 consists of nine items indicative of clinical depression plus a question about functional impairment. The nine questions were scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, with a maximum score of 27 points. Individuals with a score up to 9 points were considered to be non-depressed or mildly depressed, those with a score of 10-14 points were moderately depressive and those with 15-27 points were moderate-to-severe or severely depressive. We used a cutoff of ≥10 points as positive for depressive symptoms, as previously described.(18) The PHQ was developed by Spitzer et al (PRIME-MD© Pfizer Inc.),(19) and the PHQ-9 depression module has been further translated into the Spanish language and validated in urban and rural Latin American communities.(20)(21) The instrument is useful for estimating the presence of major depression in both clinical settings and at the population level.

Covariates investigated

Education, alcohol intake, history of epilepsy and living arrangements may be associated with clinical depression, and were identified as covariates. Education was dichotomized in up to primary school education or higher. Alcohol intake was dichotomized in <50 g/day and ≥50 g/day. For epilepsy assessment, a neurology resident conducted face-to-face interviews to identify individuals with a suspected seizure disorder, and then, a certified neurologist confirmed the diagnosis. Living arrangements were classified into two groups: individuals living with their spouses or other relatives, and those living alone.

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were carried out by using STATA version 16 (College Station, TX, USA). In univariate analyses, differences in the prevalence of mood disorders across case-patients and control subjects were assessed by the McNemar’s test for paired data (matched-pair analysis). Multivariate conditional regression models were fitted to assess the independent association between the presence of CSP and/or CV (as the exposure) and clinical depression (as the dependent variable).

RESULTS

Figure 2 depicts the reasons for not including potentially eligible individuals at each step of the enrollment process. Of 1,702 individuals aged ≥20 years identified during annual door-to-door surveys (2012 to 2018), 1,298 (76%) underwent a head CT. Of these, 51 (3.9%) had a CSP and/or CV, and the remaining 1,247 had no evidence of these cava on CT. The prevalence of brain cava decreased with age, being present in 5.6% individuals below and in only 2.2% above the median age (45 years) of the study population (p=0.002). (Figure 2)

Figure 2 Flow diagram depicting the process of enrollment and the reasons for not including potentially eligible individuals at each step of the process.

Demographics of the 51 individuals with brain cava differed from the 1,247 who did not had these cava. The former were younger (mean [±SD] age: 42.5±17.7 versus 48.1±18.4 years; p=0.033), and more often men (63% versus 46%; p=0.022) than those without cava.

Eight out of the 51 case-patients did not undergo the psychiatric interview. Three had left the village, two were disabled, two declined consent and one died after CT. This left 43 case-patients and a similar number of control subjects for analyses. Of the 43 subjects initially selected as controls, 15 did not match to case-patients or declined the interview. These subjects were substituted with corresponding controls next on the list (as detailed above).

None of the 43 case-patients had any condition known to be associated with acquired midline cava. The mean age of the 43 case-patients was 43.5±14.7 years (median age: 35 years), and 17 (39.5%) were women. As expected, these numbers were similar to those of control subjects (mean age 43.9±17.7 years [median age: 36 years], and 39.5% women). Among case-patients, 17 (39.5%) had primary school education only, 14 (32.6%) reported alcohol consumption ≥50 g/day, one (2.3%) had epilepsy, and none lived alone. Among the 43 control subjects, 15 (34.9%) had primary school education only, 9 (20.9%) reported alcohol consumption ≥50 g/day, none had epilepsy, and one (2.3%) lived alone. There were no significant differences across case-patients and control subjects in any of the covariates.

Nine of 43 case-patients (20.9%) and only two of 43 control subjects (4.7%) had moderate-to-severe depression. According to the McNemar’s test, clinical depression was significantly more common among case-patients than control subjects (OR: 8; 95% C.I.: 1.1 - 354.9, p=0.046). A conditional (fixed-effects) logistic regression model also revealed a significant association between the presence of midline cava and depression (OR: 8; 95% C.I.: 1.00 - 63.96; p=0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this case-control study nested to a population-based cohort, subjects with CSP and/or CV had increased odds of having depression compared to those without midline cava. These results provide epidemiological evidence supporting an association between midline cava and depression.

As previously noticed, the association between midline cava and mood disorders is controversial. A recent meta-analysis including nine studies found no significant association between CSP and mood disorders.(8) However, in the largest study evaluated in this meta-analysis, the presence of CSP was significantly associated with mood disorders,(9) and in three others, the Odds of having mood disorders among individuals with CSP was from 2 to 4 times greater than in those without CSP (results did not reach significance due to large confidence intervals, probably related to the sample size or the effect of hidden confounders).(12)(22)(23) On the other hand, studies attempting to find an association between CV and mood disorders are scarce, but a significant association was found in the single large series published to date.(10)

Most studies that assessed the presence of midline cava in patients with mood disorders were carried out at specialized centers and compared them with apparently healthy - often unmatched - controls. This may have resulted in a degree of selection bias. In contrast, the present study has a true population-based design in which all adults (aged ≥20 years) from the community were invited to undergo CT, and then, individuals with CT evidence of CSP and/or CV (and their matched control subjects) had a psychiatric evaluation to assess the prevalence of depression across case-patients and control subjects. This design reduces the chance of selection bias and allows for a more accurate determination of any differences in the population at large. This nested case-control study design, together with unbiased selection of subjects, the use of a validated instrument for detection of individuals with clinical depression, the assessment of case-patients and control subjects by a certified psychiatrist, the systematic evaluation of CT images, and the high level of inter-rater agreement for CT findings of interest, all argue for the strength of our results.

On the basis that persistence of midline cava into adulthood is associated with limbic system dysfunction,(3)(13) our results support the concept that clinical depression is linked to dysfunction of midline brain structures of the limbic system and probably to abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis regulation.(24)(25) In this view, our results provide a rational explanation for pathogenetic mechanisms involved in clinical depression.

The present study has some limitations, including the cross-sectional design, which precludes the evaluation of a potential cause-and-effect relationship between the presence of midline cava and depression. However, biological plausibility suggests that the direction of the relationship goes from midline cava to depression, since reverse causation in unlikely. Another limitation is the lack of MRI exams, which could demonstrate small midline cava not well-visualized by CT. However, the use of a high resolution 64 row CT scanner with 3mm slice thickness and no gap between slices, reduces this possibility. Moreover, the possible lack of visualization of small CSP may be - at the same time - an advantage of our study since small midline cava have not been associated with psychiatric manifestations. In view of the homogeneity of Atahualpa residents in terms of ethnicity and living conditions, our results might not be generalizable to other populations or ethnic groups. Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of our patients with CSP and/or CV (particularly those in the younger age group) who had no current symptoms of depression may develop them in the future. Further longitudinal studies with repeated neuroimaging and psychiatric evaluation of the study population will be helpful to answer these questions.