Introduction

Teacher training in Content Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) continues to represent one of the key educational challenges today (San Isidro, 2018; Custodio and García, 2020). The exponential increase in the number of bilingual and plurilingual schools in Andalusia (Lorenzo, 2019), Spain, has led to a readjustment of university degree curricula (Romero and Zayas, 2015). Specific CLIL training used to be limited to postgraduate courses, but now there are also specific undergraduate courses (Frigols, 2008).

The University of Cadiz, Andalusia, Spain, offers a specialization or mención in foreign language and CLIL in the bachelor’s degree in Primary Education (Romero and Zayas, 2017). This includes four optional subjects of six ECTS credits each, two of which are devoted exclusively to CLIL. The aim is for students to develop specific CLIL competences (Bertaux et al, 2009) from early stages.

A key feature of CLIL teacher training is the effectiveness of language teaching (Pavón and Rubio, 2010). Thus, in Andalusia, CLIL teachers are required to reach a minimum level of B2 according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) to work in public education (Consejería de Educación, 2011). Also, they should be able to understand that “whatever the content demands, the language has to support the content learning” (Coyle, 2010) in methodological terms. In other words, the nature of CLIL as a dual educational approach (Coyle et al, 2010) differs clearly from language teaching, as several longitudinal research studies have proved (c.f. Pérez, 2018).

This work reveals the beliefs of pre-service CLIL teachers at the University of Cadiz (2020-21) about their English as a Foreign Language (EFL) competence regarding the four skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Furthermore, it uncovers their perceptions of whether their current EFL knowledge is proficient enough to work in primary education. Finally, it attempts to find out whether alternative training needs are also expected.

Method

This is a mixed-methods research study, which adopts a descriptive approach, as it aims to identify the profile of informants as future CLIL teachers in primary education in terms of their training needs.

The participants are 95% of the university students (N=40) who regularly (80% of classroom attendance, at least) attended the subject AICLE I: Fundamentos y Propuestas Curriculares para el Aula de Primaria (AICLE I) in the academic year 2020-21. As said, this is an optional subject in the specialization in Foreign Language (English)/CLIL in the bachelor’s degree in Primary Education, Faculty of Educational Science, at the University of Cádiz. All informants are native speakers of Spanish, except for one Erasmus student whose mother tongue is Finnish. Moreover, 32 students (80%) are female while 8 students (20%) are male.

Two research tools were applied. First, the CEFR ALTE Skill Level Summaries (Council of Europe, 2001) was used to collect quantitative data. It includes a list of competences for the four language skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing). Second, the computer application Socrative (https://www.socrative.com) was used to collect qualitative data. It helped to collect the informants' views on whether their current EFL knowledge is sufficiently proficient to teach CLIL subjects in primary education, and whether they also specify training needs other than EFL.

The research was carried out during a hands-on practical session of 1:30 hours. First, the pre-service CLIL teachers were asked to highlight the CEFR Can-Do action they can perform. For this, an MS Excel file was created, which included a tab with the learners’ full names, assigning a number (1, 2, 3...) to each one of them. This file also included a tab for each student with several CEFR Can-Do actions they thought they could perform. Once it was done, they had to access the Socrative quiz to answer two questions: The first question was about whether their current knowledge of EFL is sufficient to teach CLIL subjects in primary education. The second question was about what their training needs were, with the possibility of choosing training other than EFL itself.

The data analysis is based on a statistical study supported by the perceptions and beliefs of the pre-service CLIL teachers.

Results

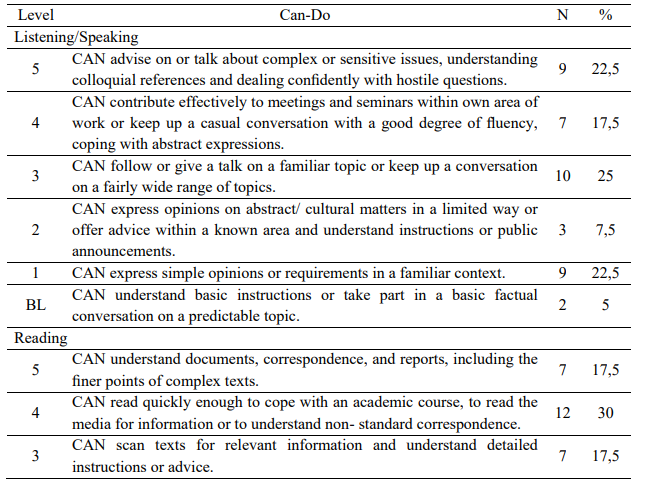

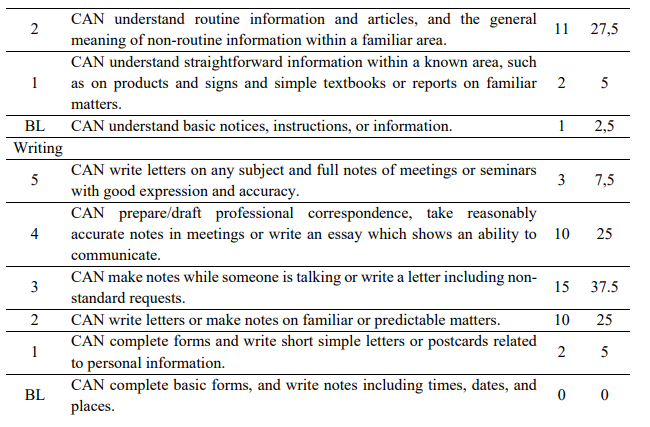

The results of the CEFR ALTE Skill Level Summaries (Can-Do list) are presented below according to the pre-service CLIL teachers' (N=40) opinions. For Listening/Speaking, 25% chose Level 3, while 22.5% did so for Levels 5 and 1, respectively. The lowest percentages correspond to the Breakthrough Level (BL) (5%) and Level 2 (7.5%). Concerning Reading, 30% chose Level 4, while 27.5% selected Level 2. Also, 17.5% picked Level 5 and another 17.5% chose Level 3. Finally, the BL and Level 1 were the least chosen options: 5% and 2.5% respectively. Finally, as for Writing, 37.5% chose Level 3, while 25% preferred Level 4 and another 25% opted for Level 2. Vis-à-vis the least selected options, Levels 5, 1, and the BL stand out with 7.5%, 5%, and 0%, respectively. Table 1 shows the data distribution among EFL skills:

As far as the proficiency EFL level of the pre-service CLIL teachers is concerned, 30% have a B1; 42.5% have a B2; 10% have a C1; and 17.5% have no official certificate. In this sense, the University of Cádiz demands a minimum level of B1 in any foreign language for students to graduate. Likewise, the Junta de Andalucía (Andalusian Regional Government) requires a B2 level to be eligible to work in public schools. So, when asked:

“Are your current EFL skills sufficiently proficient to teach CLIL subjects in primary education?", 62.5% answered “No”, while 37.5% said “Yes”.

“Is there any other specific training you consider becoming a CLIL teacher?”, 37.5% stated that they need CLIL-related methodology training.

Discussion

Written Skills Prevail Over Oral Skills

The results reveal that according to the pre-service CLIL teachers’ CEFR picks, the advanced Levels 4 and 5 relate mainly to Reading (47.5%), followed by Listening/Speaking (40%), and Writing (32.5%). Concerning the intermediate Levels 2 and 3, Reading also displays the highest percentage (45%), followed by Listening/Speaking (32.5%) and Writing (25%). The trend changes for the basic levels: Level 1 and the BL: Speaking/Listening (27.5%), Reading (7.5%), and Writing (5%). Thus, the pre-service CLIL teachers believe that their highest knowledge in terms of EFL proficiency focuses on Reading for intermediate Levels 3 and 4, and for advanced Levels 4 and 5.

As a result, a poorly developed teaching competence in oral EFL may affect language treatment (Chen and Goh, 2011) in the classroom. Vis-à-vis the Andalusian Curriculum (Consejería de Educación, 2015), the methodological guideline for foreign language teaching (área: primera lengua extranjera) points out that “in primary education, priority is given to the development of communication skills; oral skills will be emphasized in the early grades, while in the later grades, skills will be developed gradually and in an integrated way.” (p. 6; personal translation).

Low Number of Qualified Pre-Service CLIL Teachers in EFL

The data reveal that only half of the informants (52.5%) have an official B2 level, which is the minimum level required by the Junta de Andalucía to teach CLIL subjects in public education, or C1 level, which is the minimum recommended level (Lorenzo, 2019). It is worth noting that 17.5% do not yet have any official EFL certificate. The informants must, at least, obtain a B1 level to graduate. It can be then easily inferred that most informants point directly to language training: Even though more than half of them (52.5%) have an official certificate (B2), 62.5% consider that their EFL competence is not sufficiently proficient to work as CLIL teachers (Fortanet, 2013; Lorenzo, 2019). Perhaps their perception of EFL proficiency is affected by the CLIL integration of content and foreign language (Papaja, 2014). The definition of CLIL as a dual-educational approach demands specific training for both pre-service and in-service teachers (Cortina-Pérez and Pino, 2021). Among the several training areas, language instruction stands out, intending to put “[the] linguistic knowledge on a pedagogic level” (Pavón and Rubio, 2010, p. 51) at the service of students.

Methodological Training is Required and Not Just Language Training

37,5% of pre-service CLIL teachers consider that more methodological training is required -as Milla and Casas (2018) found out among in-service CLIL teachers in Almería, Córdoba, Granada, and Jaén (Andalusia)- and not only language knowledge. CLIL requires teachers to recognise the very own characteristics of the approach (Pérez, 2013) that are different from those of language and content teaching. They begin to recognise progressively the differences between CLIL and other bilingual models of education that do not consider the integration of content and foreign language (Pérez, 2020); e.g., English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI). Thus, their perception of CLIL seems to move them away from teaching practices concerning the simple translation of contents (Working CLIL Digital, 2018), among others.

Conclusions

This research reveals the existence of language training needs within the group of pre-service CLIL teachers (N=40) analysed. This is due to two main reasons: First, they must obtain a B1 level to graduate and a B2 level to work in public education. Second, whether having a language certificate or not, they still believe that further language training is required. Therefore, according to the pre-service CLIL teachers’ own beliefs:

Moreover, the novelty of this work lies in the recognition of language (i.e., EFL) training needs by the pre-service CLIL teachers. However, it is based on subjective tests of personal performance rather than on specific tests of language proficiency, which might have identified more specific training needs in reading, speaking, reading, and writing in EFL. Taking the results of this research into account, some recommendations for educational institutions (e.g., Universities) in relation to CLIL training are listed below:

Future research lines almost necessarily involve individualised monitoring of pre-service CLIL teachers in terms of language training from the very first moment they begin tertiary education. This would help to gain more and better knowledge of the development of their language skills throughout the whole bachelor’s degree. Perhaps, it would also be possible to record the steps they take after completing their university studies to check the effectiveness of the language training, getting first-hand information about whether they have entered the labour market and under what circumstances.