Introduction

COVID infection is characterized by severe acute respiratory syndrome. During the first year after its debut, it became the leading cause of hospitalization (1). This disease has infected more than 4 billion people worldwide after two years and is responsible for more than 5 million deaths (2)(3). Carod-Artal (4) suggests that the mortality rate associated with COVID infection is around 8%, with adults and older adults with chronic diseases most affected (e.g., immunosuppression).

The most reported symptoms of COVID infection are pneumonia, odynophagia, cough, and nasal congestion. After the onset, they rapidly progressed to complex respiratory symptoms with a high risk of mortality (4)(5). However, several studies highlight the neuroinvasive capacity of the virus and the development of neurological symptoms (1)(4)(5)(6).

Coagulopathy associated with COVID infection leads to systemic thromboembolism. Venous and arterial thromboembolism increases the risk of a neurological event (e.g., stroke) (7). Yamakawa et al. (7) emphasized that people with COVID infection have shown a greater predisposition to developing ischemic strokes. Thieme et al. (8) highlighted that the importance of stroke and its consequences in the population due to COVID infection is characterized by cognitive and motor effects and also by long-term disabilities.

Several studies have reported the neuropsychological repercussions of strokes, emphasizing risk factors (9)(10)(11)(12)(13). Stroke related to COVID infection cases has yet to be profiled from a neuropsychological and neuroanatomical perspective, though. Although recent investigations (14)(15)(16)(17)(18)(19) have reported cognitive associations, these are limited to highlighting cognitive impairment but do not mention the cognitive domains affected and the severity. These studies’ results also suggest that neuropsychiatric symptoms, physical repercussions, and fatigue are frequent. Studies based on neuroimaging techniques have reported dysfunctions in the cingulate cortex and brainstem (16)(20); however, few studies established associations with memory, attention, executive function, or language decline (21)(22)(23)(24)(25).

Despite the significant impact of COVID infection and its increasing interest in clinical and research practice, there have not yet been any reviews that characterize stroke cases related with this infection from a neuropsychological and neuroanatomical perspective. It is thus essential to synthesize the existing evidence of the neurological repercussions of COVID infection. Identifying neuropsychological and neuroanatomical deficits would contribute to pertinent neurorehabilitation programs, which decrease functional disability (26)(27)(28).

Based on the above, our systematic qualitative review aims to characterize the neuropsychological profile and atrophy pattern of the brain areas affected by strokes related with COVID infection in adults and the elderly. Even though cases of COVID infection have fallen worldwide, the information provided will be vital to improving the assessment and intervention process in clinical practice.

Methodology

This systematic qualitative review followed PRISMA guidelines (29) and was previously registered on the PROSPERO repository (PROSPERO 2022: CRD42022363907).

Sources and search strategy

The search for bibliographic references considered the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, including articles published between January 2020 and September 2022. The search syntax was as follows: [adult OR adults] AND [aging OR elderly] AND [COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 infection OR coronavirus infection] AND [stroke OR cerebral stroke OR ischemic stroke OR cerebral hemorrhage] AND [cognition OR cognitive decline OR cognitive impairment] AND [neuropsychological assessment OR neuroimaging OR brain imaging]. All search terms were adapted to each database (Appendix 1).

Study selection and eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied: a) adults and older adults from 30 to 75 years, b) no clinical history of previous stroke, c) analytical observational studies of diagnostic tests published in English between January 2020 and September 2022, and d) studies reporting neuropsychological and neuroimaging assessment. Exclusion criteria were: a) editorial articles, systematic reviews, protocols or theses, and b) patients with a dementia or mild cognitive impairment diagnosis.

Data extraction

To eliminate duplicate articles, we imported the studies to the Rayyan software (30). Subsequently, three reviewers (I.B-B., M.C-H., and C.R-J) applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria independently. In case of doubt, the research team retrieved articles’ full texts when decisions could not be made based on the title and abstract. Based on his experience (D.T-R), a fourth investigator participated in the consensus selection of those studies presenting discrepancies (15%) regarding their inclusion.

Risk of bias and quality assessment tool

To assess the bias risk and the articles' methodological quality, we used the QUADAS-2 tool (31). For the bias analysis, four key domains were assessed: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing domain. Methodological quality was evaluated based on patient selection, index test, and reference standard domain. Finally, high, low, and unclear criteria classified each included study.

Data synthesis strategy

The general characteristics of the studies, such as year of publication, population, mean age, type of stroke, time from neurological symptoms, COVID severity/phase, and Intensive Care Unit admission, are in Table 1. Table 2 presents the principal neuropsychological declines and neuroanatomical findings in patients with stroke related to COVID infection, and the main instruments/measures used. It is important to mention that the changes in each neuropsychological capacity, shown in Table 2, were classified into increase or decrease based on the score reported for the MoCA test.

Results

Literature search

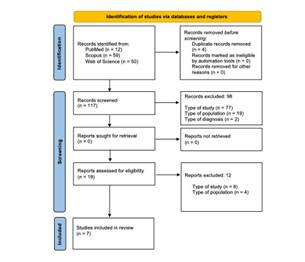

The article selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart (see Fig. 1) (29). We identified titles and abstracts of 121 articles, considering four duplicates. After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria to the 117 studies screened, 98 articles were excluded. 19 full texts were analyzed to assess their eligibility; however, after the analysis, eight articles were excluded. Finally, seven articles were included for review. (Figure 1)

General characteristics of the articles

Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the seven studies (32)(34)(35)(36)(37)(38) included. For publication years, 2021 stands out with three articles, followed by 2020 and 2022 with two studies, respectively. The total sample was 1,081 adult and older adult patients, with 664 cases of patients with COVID infection-related strokes (mainly ischemic stroke). For age and gender variables, the mean age for stroke patients related to COVID infection was 60.6 years. Most patients were male (60%), for both stroke-related or not with COVID infection. The timeframe for expressing neurological symptoms related to COVID infection was 2 to 12 days. The most reported COVID infection severity was mild-moderate, and the acute phase was reported in 6 articles. Finally, regarding the need for Intensive Care Unit admission, results suggest that 57% of the articles reported no need. (Table 1)

Table 1 General study characteristics.

| First Author | Participants | Sex | Sex | Mean Age sCOVID-inf (years, SD) | Age range | Type of stroke (%) | Time of neurological symptoms (days) | COVID infection severity (%) a | COVID infection phase | ICU admission | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sCOVID-inf/ tCOVID-inf | ♀ ♂ | ♀ ♂ | (years) | |||||||||||||||

| % tCOVID-inf | % sCOVID-inf | 30-49 | 50-69 | 70 + | Is | Hem | Throm | Mil-Mod | Sev-Cri | Yes | No | |||||||

| Meppiel et al. (2021) (32) | 57/222 | 38.7 | 61.3 | 40.4 | 59.6 | 65 (-) | - | ✓ | ✓ | 92 | - | 8 | 12 | 65 | 35 | Acute phase | ✓ | - |

| Chaumont et al. (2022) (33) | 18/60 | 40 | 60 | - | - | 66 (-) | - | ✓ | ✓ | 94 | 6 | - | 5 | 57 | 43 | Long COVID infection | - | ✓ |

| Chougar et al. (2020) (34) | 66/73 | 34.2 | 65.8 | - | - | 58.5 (15.6) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 65 | 31 | 4 | 6 | 52 | 48 | Acute phase | ✓ | - |

| Shahjouei et al. (2021) (35) | 432 stroke patients associated with COVID-19 | 42.4 | 57.6 | 42.4 | 57.6 | 65.7 (15.7) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 75 | 21 | 4 | 3-5 | - | - | Acute phase | - | ✓ |

| van Lith et al. (2022) (36) | 70/200 | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 100 | - | - | 2 | - | - | Acute phase | - | ✓ |

| Sabayan et al. (2021) (37) | 15 stroke patients associated with COVID-19 | 20 | 80 | 20 | 80 | 65 (15.6) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93 | 7 | - | 7 | 27 | 73 | Acute phase | ✓ | - |

| Ashrafi et al. (2020) (38) | 6 stroke patients associated with COVID-19 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 43.5 (7.42) | ✓ | ✓ | - | 100 | - | - | 2-6 | 83 | 17 | Acute phase | - | ✓ |

*Notes. ✓: Specified. -: Not specified. sCOVID-inf: stroke patients related to COVID infection. tCOVID-19: total of patients related to COVID infection included in the study. SD: Standard deviation. Is: Ischemic. Hem: Hemorrhagic. Throm: Thrombotic. Mil: Mild. Mod: Moderate: Sev: Severe. Cri: Critical. ICU: Intensive Care Unit. a: According to National Institute of Health guidelines.

Neuropsychological and Neuroanatomical perspective

Table 2 reports that neuropsychological assessment was based mainly on the MoCA test and the criteria established in NIHSS. The declines reported in patients with COVID infection-related strokes include alterations in spatial and temporal orientation, attention, memory, visuoconstructive skills, and linguistic skills (such as expressive, comprehensive, naming, and semantic and phonological fluency).

The most reported neuroimaging techniques were CT and MRI. Cortical involvement comprises the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes, although involvement of the corpus callosum, brainstem, and subcortical areas is also reported. The damage pattern is limited to not only the left but also to bilateral affection. (Table 2)

Table 2 Neuropsychological and Neuroanatomical characterization.

| Ref. | Neuropsychological characterization | Neuroanatomical characterization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruments/Measures | Neuropsychological findings | Instruments/Measures | Hemisphere localization | Neuroanatomical findings (stroke localization) | |

| (32) | GNE | (: MM, T-S-O, VCA, PF, RE, SS, Syn-Gram abilities (: AN | MRI, CT, CSF, EEG, ENM | L, BI | Frontal, parietal, occipitotemporal and cerebellar areas. |

| (33) | mRS, EQ-5D-3L, CDS, MoCA, HADS | (: MM, DR, EF, AT, OR, VSA, AC, RE, PF | CT | NE | Subcortical areas. |

| (34) | Clinical data collected by neurologists. | (: AT, T-S-O | MRI, EEG, CSF, CT | NE | Corpus callosum, basal ganglia, sustantia nigra, globus pallidus, and the nigrostriatal pathway. |

| (35) | NIHSS | (: T-S-O, AT, CS, ES, PF, SF, NAM | MRI, CT, TOAST | NE | Basal ganglia, superior sagittal sinus, and sigmoid sinuses. |

| (36) | HADS, PCFS, mRS, MoCA, TICS | (: MM, VCA, AT, EF, SF, PF | MRI EC | L, BI | The results suggest that the damage is mainly in cortical regions; however, the affected brain areas are not deepened. |

| (37) | NIHSS, mRS | (: T-S-O, LA, MM, AT | CT MRI | L, BI | Striatum, brainstem, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. |

| (38) | NIHSS | (: LA, CS, ES, Syn-Gram abilities, SF, PF, NAM, AT, MM, EF. (: AN | ECG CT TCCS EC | L, BI | Basal ganglia, caudate, lentiform nucleus, and anterior horn of the internal capsule. |

*Notes. Ref: References. : Decrease. : Increase. GNE: General neuropsychological evaluation. mRS: Modified Rankin Scale. EQ-5D-3L: 3-level version of the EuroQol five-dimension scale. CDS: 35-item version of Cognitive Difficulties Scale. MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment. HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. PCSF: post-COVID functional scale. TICS: Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. MM: Memory. T-S-O: Temporal and spatial orientation. VCA: Visuoconstructive abilities. PF: Phonological fluency. RE: Repetition. SS: Spontaneous speech. Syn-Gram: Syntactic-Grammatical. AN: Anomia. DR: Delayed recall. EF: Executive function. AT: Attention. OR: Orientation. VSA: Visuospatial abilities. AC: abstraction capacity. CS: Comprehensive skills. ES: Expressive skills. SF: Semantic fluency. NAM: Naming. LA: Language abilities. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging. CT: Computed tomographic. CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid. EEG: Electroencephalogram. ENM: Electroneuromyography. TOAST: Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. EC: Echocardiography. ECG: Electrocardiogram. TCCS: transcranial color-coded duplex ultrasonography. NE: Not specified. L: Left. BI: Bilateral.

Risk of bias and methodological quality of the articles

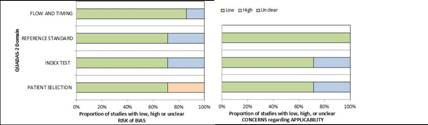

The analysis of the seven articles with QUADAS-2 (31) appears in Fig. 2. Regarding the risk of bias analysis, 72% were classified as low risk in patient selection, while 28% had uncertain risk in the test index and reference test domains. 86% were considered low risk in flow and timing. On the other hand, in the methodological quality assessment, 72% of the studies were classified as low risk for patient selection and test index. 100% were classified as low risk in the reference test domain. (Figure 2)

Discussion

The present review aimed to characterize adults and older adult patients with stroke related to COVID infection, using neuropsychological and neuroanatomical perspectives. Our findings suggest that orientation, attention, memory, visuoconstructive abilities, and language experienced a reduction in their capacity. On the other hand, the left-brain and bilateral areas most affected are frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital, in addition to the corpus callosum and subcortical regions.

Stroke and prevalence

The prevalence of stroke and its association with gender variables has been getting a grownup interest in research practice. Studies report opposites outcomes since they suggest no gender differences (39), while other founding suggests higher prevalence in women (40)(41). In line with our findings, Mao et al. (42) indicate that stroke is more common in men. Although the evidence shows disagreement, there is a consensus that the prevalence in men and women depends on age. Studies propose that stroke is frequent between 60-64 years, which is consistent with our results in patients with COVID infection-related strokes who report a mean age of 60.6 years (43)(44).

Several studies have reported a considerable increase in strokes among people under 55 years in recent decades (45)(46)(47). Putaala et al. (48) performed a multicenter study in Europe, finding that the incidence of stroke in women surpasses the incidence of men for age groups under 35 years, while in the age group between 35 and 50, the highest incidence in men prevailed. On the other hand, the evidence highlights that female hormones could play a protective role in the expression of neurological events (even in preclinical models), which could justify the small number of women in our analyzed sample (49)(50)(51)(52)(53).

Ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke

The type of COVID infection-related stroke appearing in our results concords with the current evidence, which reports a high prevalence of ischemic stroke (54)(55)(56)(57). An observational study (44) suggests that 31% of COVID infection patients manifested thrombotic complications, followed by deep vein thrombosis and ischemic stroke. It should also be noted that our results show an important number of hemorrhagic strokes in older adult. The subjects’ age range has been associated with a higher risk of developing mild cognitive impairment or dementia (58)(59)(60)(61). On the other hand, a previous meta-analysis (62) suggests that in stroke patients related to COVID infection, the damage shows greater extension and severity, being the most frequent affliction in large vessels and multiple territories.

Neuroanatomical correlates in stroke

Previous studies highlight that neuroimaging techniques such as MRI and CT are essential to diagnostic accuracy and differentiation between the different types of strokes in the acute stage (63)(64)(65)(66). Our findings report that in patients with COVID infection-related strokes, the damage can affect both cortical and subcortical areas. Indeed, studies have reported that subcortical regions such as the putamen, globus pallidus, and insula also tend to experience significant damage (67)(68).

Case studies in patients with COVID infection-related strokes agree with our brain areas reported. Avula et al. (54) studied four patients with COVID infection and stroke, reporting a significant decrease of white and gray matter in the parietal and occipital lobes, along with predominantly left frontotemporal and corticospinal tract hypodensity. Their results highlight that cognitive decline tends to affect these patients’ language; however, they establish an association between this neuropsychological decline and motor repercussions with damage to the basal ganglia and internal capsule. These data mesh with the findings of another COVID infection case study (69), but both left and right hemisphere damage was reported in the five patients analyzed.

Stroke and its neuropsychological implications

It is postulated that typical post-stroke cognitive domain deficits depend on the injury type, extension, and localization (70). Executive function, working memory, and information processing speed are the most frequent cognitive domains affected, with more severe deficits in older adults (71)(72)(73). Our results in patients with stroke related to COVID infection, similar to other studies, highlight the compromise in orientation, attention, and language (74)(75)(76)(77).

Sharifi-Razavi et al. (78) presented 3 cases of stroke secondary to COVID infection, suggesting that declines in orientation, memory, and language (e.g., aphasia) are highly prevalent in these patients. This is consistent with our findings and the reports from post-COVID patients without stroke. However, in their follow-up study, Mattioli et al. (79) suggest no significant neuropsychological impairments in patients with stroke related to COVID infection.

Aphasia classically tends to be affected in typical post-stroke patients, with mainly left hemisphere damage (80)(81). However, our study also suggests bilateral affection in patients with stroke related to COVID infection, which differs from reports among the non-COVID-infected population. This could indicate possible right hemisphere impacts in this group of patients, perhaps in cases of long COVID. This makes it necessary to investigate possible linguistic disorders secondary to atypical damage in the non-dominant cerebral hemisphere, such as the right hemisphere, which tends to be not associated with linguistic deficits (82).

Neuropsychological assessment

We reported that the NIHSS scale and MoCA test were mainly used to register deficits in patients with stroke related to COVID infection. NIHSS has been widely suggested in the literature, highlighted as an attentive scale for evaluating post-stroke patients related to COVID infection (40)(54)(69)(83)(84)(85). Although there is consensus on the use of this scale, it does not allow an exhaustive evaluation of the different cognitive-linguistic domains in post-stroke patients.

Our results report a wide use of the MoCA test as well. Chiti and Pantoni (86) highlight that it is not frequently used in evaluating stroke patients, but is common in people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Despite this, it has excellent psychometric properties to detect cognitive alterations. It has shown good sensitivity and specificity indexes to identify cognitive declines in post-stroke patients (87)(88)(89). Khaw et al. (90) suggest that the MoCA test should be used cautiously in post-stroke people, because it does not consider either a detailed neuropsychological assessment or an exhaustive language evaluation. So far, few studies (91)(92) have focused on language impairment in patients with COVID infection. Those studies highlight that lexical fluency and naming performance could affect these patients; however, they suggest that sociocultural language differences must be considered during assessment.

Limitations

Our systematic review does not present a meta-analysis, focusing only on qualitative analysis. Likewise, we only considered three databases for articles search; therefore, our findings must be interpreted carefully. Moreover, most of the studies defined cognitive impairment using only the MoCA test and NIHSS; however, for some papers, symptoms were reported by clinicians only. Finally, the neuropsychological assessment in all the studies included does not report test scores. Neuropsychological deficits in patients with stroke related to COVID infection were thus performed from a general perspective (qualitative interpretation of the main findings in each article).

Clinical contributions

A previous review by Vanderlind et al.(93) focused on patients' neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric sequelae related to COVID infection; however, they did not establish a neuroanatomical correlation with neuropsychological symptoms. Wilson et al. (94) highlight the importance of neuropsychological performance on stroke patients related to COVID infection, suggesting the importance of accurate detection for appropriate treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review concerning COVID infection-related strokes to characterize this clinical population from a neuropsychological and a neuroanatomical perspective. Our results provide relevant information for clinical practice, suggesting a generalized profile for implementing specific intervention programs in the acute stage of patients with COVID infection-related strokes and post-COVID patients without stroke. These interventions will reduce functional disability index value and will contribute to delaying the progression of vascular dementia.

Future directions

Although our study focused on the neuroanatomical correlation from a structural damage perspective, future research should consider functional MRI to determine the pattern of brain connectivity affected in patients with COVID infection-related strokes and its implications in the chronic stage and long COVID cases. Finally, the assessment process must establish unified cognitive-linguistic protocols for these patients and the general stroke population.

Conclusions

Results show similar cognitive deficits to those reported in typical strokes. Memory, orientation, attention, and executive function decline are the most common symptoms of COVID infection-related stroke patients, which concords with reports from the general stroke population. Aphasia is also reported, but not only limited to left-side lesions. Cortical and subcortical involvement is postulated in these patients as well, and alterations are mainly presented in the left hemisphere or bilaterally in the clinical population with ischemic stroke.

Finally, it must be noted that the neurorehabilitation process should be performed in the acute stage. Early intervention in this population is critical, considering their susceptibility to developing dementia secondary to stroke.